Since the journal was launched in May last year, Question of Cities has brought you thematic editions on natural and built environments, sustainability, Climate Change, Right to the City, gender and cities, heat and floods to list a few. Our format of reported essays and interviews means in-depth and long pieces, going against the current trend of generating bite-sized content on any and all subjects, but we believe that meaningful engagement with issues calls upon readers to spend time and mindspace on a piece.

In the past year, Question of Cities featured 28 cities at least once and published more than 110 essays and stories about these cities from how they were planned, what ails them, what can be the way ahead as they grapple with serious issues. We are proud to have featured the work of some of the best-known writers and thinkers in India, and the world, on cities and city-making.

For the anniversary edition, we went back to our contributors to have them ask questions to the authorities in their cities about what they wrote – or any other pressing issue – to add a new layer to their published work. Here’s the priceless compendium, worth saving, featuring some of our writers in alphabetical order.

Photo: Dnyaneshwari Burghate

Amita Bhide, Professor of Habitat Studies at the Centre for Urban Policy and Governance, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai

“I see Mumbai at two levels. Where I live needs to be close to work, someplace I can relate to and can participate in, a place I can shape and where I have several opportunities. The city is a place with multiple dynamic interactions across classes, castes, and religions…I want to talk to the authorities about the deterioration and unplanned development of Mumbai happening through the redevelopment projects. They are looking at development through short-term interests. Where are the long-term interests? Many IAS officers have absolutely no binding for the city they serve.”

“The construction of the city happens at multiple levels, we need to think about gender at all the levels. We neglect practical and sometimes easy solutions which may help women and other genders. It is also shameful that our plans and designs don’t think about building at every level, which can enable women to take the fullest advantage of the opportunities that cities provide. It may be in terms of mobility, public conveniences like toilets, and facilities like care centres. These things really trouble me.”

Bhide’s essay says it is important for urban planning to actively recognise the impacts of particular city designs on the life of people, particularly of women, given the stark outcomes seen in parameters such as work participation rates and safety.

Anu Sabhlok, professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Mohali

“The unprecedented expansion is not only in Chandigarh but pretty much in all cities across India. Chandigarh already had a history of labour colonies, the first one was around the 1960s and, as the city kept getting constructed, more migrant workers came. Then, other areas emerged out of urban villages that predated the city or peripheral areas. Over the years, people in the labour colonies built houses without help from the government, and thriving communities have emerged…In the past few decades, there has been a push towards building a world-class city, bling buildings, slum-free city – a sanitised version of what we want the city to appear. The government is not thinking of enhancing existing neighbourhoods but is demolishing labour colonies and putting people in ‘affordable housing’ outside the city. But, it is far from affordable because the transportation cost and rent add to their expenses.”

“One of the major things that the Chandigarh administration can do is not to look at these colonies as problems. Second, Chandigarh is a tri-city area — Panchkula, Mohali, and Zirakpur – with cities not even 10 kilometres apart; their administrations need to talk more often for solutions through a regional approach. Third, and this is radical, should large-scale construction projects have a mandatory budget allocation towards housing for workers not only in Chandigarh but across the country? The low wages for workers have subsidised the construction industry which needs to be removed.”

Sabhlok’s essay showed how Chandigarh emerged as a city designed for neo-liberal India with its grid hierarchy, segregation of functions, and wide tree-lined avenues attracting capital and property-owning class – but excluded labour. Its sector-based plan aimed to eliminate “disorder” prescribing activity and “legitimate” residents who could occupy them, which was not a surprise because its planner, Le Corbusier, saw successful urbanism as a profit-making venture.

Photo: Darshan Desai

Darshan Desai, editor of Development News Network and media educator

“Ahmedabad is a study in contrast. It is one of the few medieval cities which is still prospering but there is total urban chaos. Historically, its commercial and cultural aspects fused well but it is no longer the same. Development looks like sliced sections, some good and others ignored. Its water bodies are drying up, and green spaces are decreasing over time. My question to the government: What is your understanding of development?”

“The Sabarmati riverfront in Ahmedabad is a testimony of the development dichotomy in Gujarat. It is a beautiful riverfront with a nice driveway along the river, a fun place. But at its end of the riverfront starts a dead river and runs 120 kilometres mostly as a dumping ground for waste and effluents. Water has depleted, its quality is so bad that even the cattle can’t drink it. The Sabarmati riverfront project should not be replicated anywhere in the country.”

Desai’s essay explored how Sabarmati, a natural river, was transformed into a tank of stagnant water for commercial and recreational purposes. Environmentalists and activists fighting to save the river face a huge challenge.

Harini Nagendra, professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University, author

“Bengaluru is very much a city of nature — trees, lakes, birds and vegetation. It shapes the way people think, feel, act and behave, but increasingly less so. This is the city that we loved but it is changing over time. I would question the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), the water board, the Karnataka electricity board, the pollution control board and other authorities: How can you look at development without looking at nature as the central pin around which development evolves? Environment is always a peripheral add-on, they just add a few trees or occasionally restore some lakes. Climate Change will trigger all kinds of environmental disasters. I want to ask them: How are you going to survive this unless you focus on restoring nature?”

The interview with Nagendra focused on how flooding in Bengaluru should be an eye-opener for agencies to plan for the city as a whole rather than allow private fixes of certain areas.

Photo: Shubhro Jyoti Dey/ Unsplash

Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator of South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People (SANDRP), water sector expert

“We should have the intention to protect our rivers, which is missing. No agency is interested in this. Once they decide they want to protect rivers in a city, then they need to have a policy, know which aspects of the city are related to the river, and evolve governance for its protection. For most of the past three decades, I lived in Delhi which, including the NCR capital region, has the second-largest population in the world and is expected to overtake Tokyo in the next six-seven years. The floodplains and water bodies here need protection.”

“I would like to ask the central government what it has done for the protection of the rivers and water bodies in Delhi? Whether it is the environment ministry at the Centre, the urban development ministry, the Central Pollution Control Board, or the Delhi pollution control board, Delhi development authorities, and the environment department of Delhi, the first step has to be intention, then drafting a policy. No city can be smart unless it is water-smart. Delhi doesn’t harvest water or treat its wastewater, doesn’t protect its river and water bodies, doesn’t recharge groundwater, doesn’t protect its biodiversity, and instead demands so much water from outside.”

Thakkar’s essay explored how rivers and their ecosystems in cities are being ruined in the name of development with projects stripping them of their ecology, changing their geographical features, and leaving a lasting damage on marine life and people whose livelihoods depend on rivers.

Khaliq Parkar, urban sociologist and PhD researcher at CESSMA, Université Paris Cité

“The Smart Cities Mission (SCM) began with a call for participatory planning but this has been lost somewhere down the road. As most projects are nearing completion or have been abandoned, it is probably too late to engage the public in shaping them. At the same time, we do have digital infrastructures set up and data being acquired in many cities. The SCM must pave the way for academics and communities to have direct access to the collected information to make better decisions, and to also ensure transparency, encourage participation and open innovation.”

“Our urban data has always been fragmented, unclean, siloed, and closed. Even in SCM cities, despite digitisation of maps and datasets, municipal agencies have little access or no capacity to work with this data. Standardisation of data is the first step that some cities are achieving under the SCM. Making this data accessible between departments and agencies should be the second stage, followed by open access to city data to the public. At the same time, city agencies need consistent capacity building and not wholly rely on consultants and vendors.”

Parkar’s essay spoke about developing an open data regime that will ensure the democratic goals of transparency, accountability, and scrutiny.

Photo: Creative Commons

Mansee Bal Bhargava, Ahmedabad-based architect and trans-disciplinary professional of sustainability

“The best way to make Gandhinagar liveable is to densify the blocks. Though they are dynamic, the moment you step out, it stops feeling like part of the city. It would have been nicer if the layout was more of a cluster instead of the gridiron type. I would like to make Gandhinagar more inclusive in terms of class. When I was living in Rotterdam, my apartment building had one-bedroom homes as well as five-bedroom homes. The entire neighbourhood was built this way post-war with the intention of housing different classes together. The buildings look the same from outside, you can’t tell between a small house and a big one. That, for me, is inclusive and equitable.”

“Gandhinagar is clearly a closed city – not because of its layout or design alone, but its proximity to Ahmedabad and the anticipation that it is for government officials. Chandigarh also suffers from this problem to a large extent. But government officials working in Gandhinagar mostly live in Ahmedabad, now there are metros and other transit systems between the cities. So, it still remains a closed city, unless we populate it the way it was envisaged.”

The interview with Bal Bhargava focused on Gandhinagar as a planned city, its drawbacks, and the unsustainability of the Gandhinagar-Ahmedabad corridor.

Minal Pathak, professor at Ahmedabad University’s Global Centre for Environment and Energy, and lead author of IPCC report 2022.

“I have grown up in Ahmedabad and lived here for a long time so I may be biased but it’s a lively vibrant city with a great mix of old heritage and modern development. But some things about Ahmedabad are changing and those are not great – we don’t have enough public spaces, roads are congested with too many SUVs and luxury cars. We have to bring the balance back. On heat, Gujarat’s Heat Action Plan should be part of the overall urban plan, not just a standalone. It should be a mix of preventive and reactive measures so that cities are prepared for combating heat, not merely when a heat wave strikes.”

“I would like to ask the authorities if they are actually thinking about what the city will look like in the next 30 years. And if there are discussions governed by the future, not just short-termism. Are they thinking about what they are going to do about the environment and climate? I would finally like to ask them if they are going to continue with this incremental approach or are they ready to take some steps to call out to the real estate lobby.”

The interview with Dr Pathak explored the connection between urban development and heat. “Urban heat phenomenon will be pretty bad because we are building our cities with a lot of concrete,” she said.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Pranay Kumar Swain, Professor of Sociology, National Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhubaneswar

“My city is where my heart is. Every lane and sub-lane that I grew up in wraps me with nostalgia. Bhubaneswar has come a very long way in terms of its infrastructure and amenities. From a sleepy town of the 1990s, it has positioned itself as an educational hub of eastern India and a centre for new-age entrepreneurs. Its demographic profile may be like other Tier-II or Tier-III cities in India but it has embraced everyone as its own…The roads and other public infrastructure is refurbished when there is a big event. However, civic authorities appear content with these one-time glitters. Maintenance of most of the ‘new’ installations is needed. Regulation of traffic is a major issue. Every year, drainage and sewage lines are laid and re-laid but a spell of heavy rain clogs many roads. How can all this be addressed? Another question for the authorities is why we don’t see adequate public toilets across the city.”

Swain’s essay delved into how Bhubaneswar is more cosmopolitan than the city it started out as, attracting investments and more employment.

Shalini Singh, Delhi-based journalist and co-founder of People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI)

“I happen to live in a ‘posh’ south Delhi colony, courtesy my paternal grandfather. The security of formative dwelling allowed me to be ‘freer’ in my choices. Within a few kilometres from my home, families live on pavements, under flyovers, in illegal colonies, makeshift homes. There’s also enormous opulence as you move towards the centre where billionaires reside in acres of greenery and waterfalls. Delhi, like India, is great for those who can afford it, a nightmare for ones who can’t. The difference between the two sections is palpable. The city carries the stamp of inequality in its localities.”

“The two per cent of Yamuna River flowing through Delhi has caused 80 per cent of the pollution, it is officially a sewer line today. This reflects our development choices. Echoing what the farmers of the Yamuna asked me when I interviewed them, I would ask Delhi’s municipal bodies why the river is not clean if Rs 3,000 crore have been spent since 1993 on cleaning it, why the river was allowed to degrade, and where has that money gone. Thousands of people have been rendered homeless and their livelihoods uprooted each time ‘development’ is proposed around the Yamuna, such as during Asian Games and Commonwealth Games, and recently a biodiversity park. Also, there are reports of creating women-only parks but why aren’t we thinking holistically about women’s safety so that such segregated spaces may not be required?”

Singh’s essay explored how at the Conference of Parties, COP27, which she covered, countries did not talk about details and projects that will secure urban ecology and protect people, leaving it to city governments.

Photo: Creative Commons

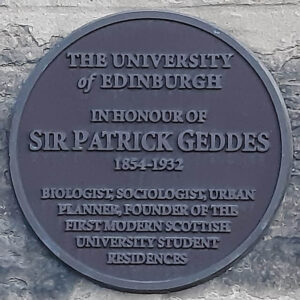

Sukhada Tatke, independent writer based in Edinburgh, reported and wrote also from Mumbai and Houston

“Edinburgh is like a lover — I know it viscerally, its form feels grafted in my every pore, its twists and warts, blips and faults are recognisable even from a distance. Every time it opens up to me like an embrace and draws me close, I know why I chose it and it me. I have many questions – from the transport authorities, I want to know why bus fares are so high, why buses are not punctual? To the housing authorities, I want to ask ‘What are you doing to regulate rents? How do you plan to control real estate sales when developers and investors out-shark first-time buyers?’ I want to know what is being done to improve the quality of social housing.”

Tatke’s essay brought Edinburgh to life through the eyes of Sir Patrick Geddes, biologist, conservationist and town planner, for whom the city was both an inspiration and a workshop.

Photo: Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change/ Creative Commons

Vivek Chattopadhyaya, principal program manager of the air pollution control programme, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi

“Delhi, notorious for its severe air pollution, continues to face challenges in improving its air quality despite various measures taken over the years. Although there are signs of change – PM2.5 annual average concentration reduced from 115 micrograms per cubic metre in 2018 to 98 last year — the city needs to achieve the target of 40 micrograms per cubic metre. Vehicular pollution, emissions from industrial, domestic, dust, refuse burning are among the issues that need to be addressed. Transport sector contributes almost half of the PM2.5 load. Delhi is an example of what can go wrong in a mega city.”

“To transform Delhi into a more livable city, planners must prioritise sustainable urban planning principles which includes developing a well-connected public transport network, designing pedestrian-friendly streets and cycling infrastructure, and discouraging private vehicle use. Collaboration between authorities, urban planners, experts, and the public is crucial for long-term solutions. My question to the National Capital Region Planning Board is what has it done over the years about the issue. Several industries shifted out from Delhi, but they operate in other NCR cities. As electricity supply is erratic and they depend on gensets, I want to know why renewable energy-based solutions are not promoted. I want to ask the Delhi government, are we tracking health and air pollution data of all socio-economic classes and all age groups to know the impact of the inaction?”

Chattopadhyaya’s essay deep-dived into how public campaigns and courts’ orders have yielded action plans on air pollution but concrete steps, coordination between different agencies, and comprehensive management of air quality remain challenges for Delhi.

Yunus Lasania, Hyderabad-based journalist

“Hyderabad is a city with continuity or continuous history. It’s home to myriad communities and different people who built something worth cherishing now and for the future. For me, it’s also more of a sense of belonging, the appreciation of small but important things like Irani chai and Irani cafes. Unfortunately, governments have let things decay, and only applied bandages when something broke. Why don’t we have better flood management? Why don’t we have a stronger policy to protect heritage monuments? The questions are endless. I want development projects to be thoughtful and practical – Tank Bund doesn’t have to be a racing road, it’s important to protect the Hussain Sagar Lake around which Tank Bund road is built, save our greens and our built heritage.”

Lasania’s essay looked at how Hyderabad’s rapid urbanisation ignored the principles of sustainability resulting in flooding and other climate events, without the inability to deal with them.

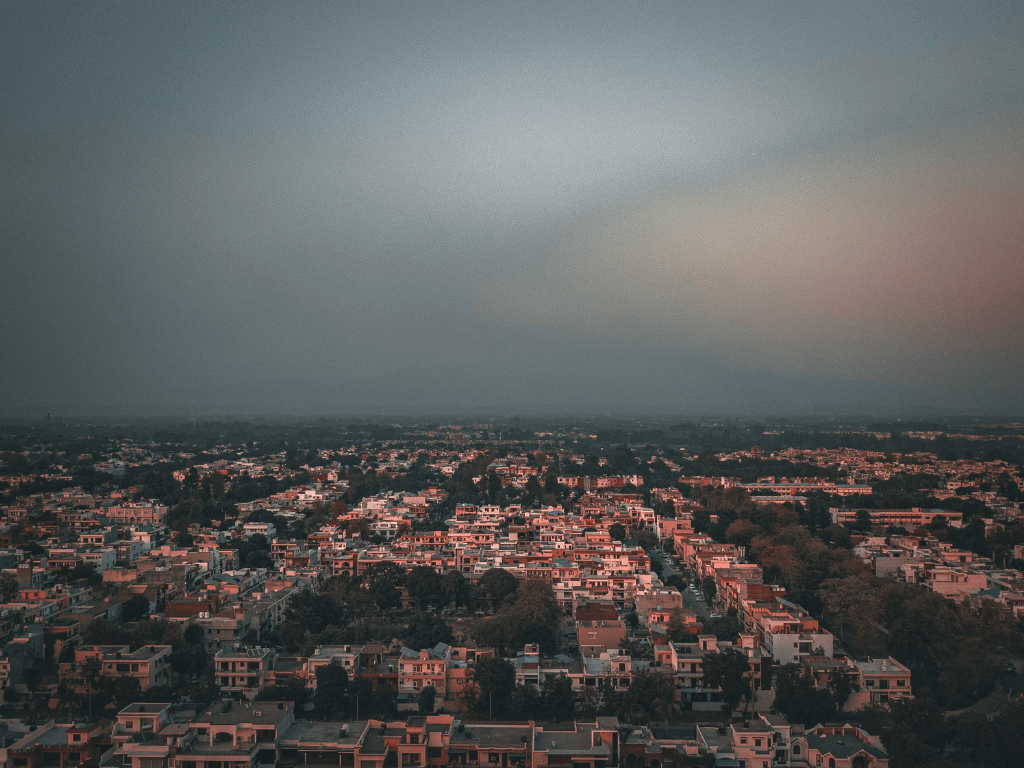

Cover photo: Chandigarh; Abhiraj Chahal via unsplash