The tourist aura at Sharm el-Sheikh, the coastal Egyptian town which played host to the annual Conference of Parties (COP27) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, can lull the senses into a languid comfort that all will be well with the planet we live on. This venue should ideally lay the roadmap for the world to move urgently and purposefully on Climate Change, which would provide cues to cities around the world to address the issue, but the COP turned out to be a jamboree for national leaders with little space for on-ground local action to be displayed.

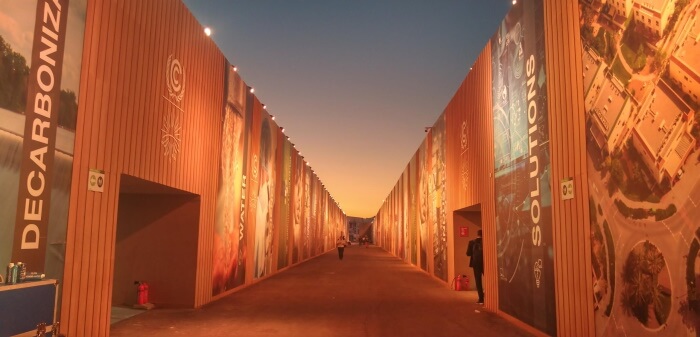

For those familiar with New Delhi, the Sharm el-Sheikh event was akin to a trade fair at Pragati Maidan. It had diversity but also stark contradictions from the Boston Consulting Group to Brahmakumaris, seeing Coca Cola as a sponsor of the ecologically-significant event, and more. Beyond the over-priced $10 burger meals, long queues, water shortage and surveillance concerns, given the warm glow of solidarity and shared experiences, it was possible to feel hopeful about the paths taken to address Climate Change and its impact on millions.

Yet, something was amiss as it has been for previous editions of the COP: Absence of the urban voice or city governments at the big table. The COP27 might have begun to remedy that with a couple of initiatives – which were lost in the din over the Loss and Damages Fund – but it is too early to say that cities’ representatives had the centre-stage here.

Cities key to successful mitigation plans

It is well acknowledged that, globally, cities are the biggest consumers of fossil fuels and the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. Cities consume 78 per cent of the world’s energy and are responsible for nearly 70 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the UN Habitat.[1] Cities account for more than 70 per cent of global carbon-dioxide emissions, according to the World Bank who had a pavilion at COP27 and whose word was gospel for the suits at the venue too.[2] The CO2 emissions are nearly three-quarters of the total emissions; industries, motorised transport, and carbon-intensive infrastructure in cities are the main culprits. Any which way we slice it, Climate Change has cities at its centre though its impact is felt beyond the urban too.

After the conference, national governments and multinational corporations, which hold the fort at COP27, devolve their responsibilities and commitments to regional and local levels in their countries. It is expected that national governments would have consulted their regional or local governments before making commitments at the COP and collated their approaches in mitigating and adapting to Climate Change. However, if the future success – or failure – of the plans firmed up at the global level depend heavily on the actions taken at the regional or local level, it may be time to hear from them directly and have them occupy seats at the big table.

The COP27 made some space for mayors and leaders of cities – there was the launch of the Sustainable Urban Resilience for the Next Generation (SURGe) initiative focusing on urban climate finance to build resilience in cities, and the roll out of the Beat the Heat: Nature for Cool Cities Challenge to focus on nature-based solutions in cities. But city governments have to be seen and heard more.

After the commitments India made at COP26 last year, the government introduced the Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill 2022 in Lok Sabha in August. It mandates the use of non-fossil sources and trade in carbon credits to expedite the decarbonisation of India’s economy. It also includes a code for office and residential buildings. However, there are challenges about who will regulate the carbon credit market or how a commercial establishment can choose an electricity source. Translating international commitments in cities is easier said than done.

At the COP, countries don’t talk about their cities or the nitty-gritty details and projects that will secure urban ecology and protect people; that is left to city governments. Cities are largely responsible for mitigating climate-related disasters and their impact, and develop early warning systems. They are supposed to draw up comprehensive city-level climate action plans on cues from the central government but cities like Mumbai, Bengaluru, Kolkata, Delhi were not part of India’s discourse at COP27. There was a Mumbai team at the COP26 though not in the official delegation, Uttar Pradesh was apparently supposed to send a team this year but did not.

Photo: Shalini Singh

Cities matter

Cities are – and will remain – key to how India’s international commitments are met; much lies on how cities draw up comprehensive climate action plans to adapt to intense and frequent floods and severe heat waves, and plan mitigation measures for the long-term. India’s multi-tier governance structure means that the central government gives policy signals or guidelines based on which individual cities or urban regions and states must make their plans. A few cities have such plans, but many do not.

Those that have rolled out city climate action plans have preferred to draw them up with contracted career experts rather than hold consultations with people who live in the cities. Besides, they tend to focus on the low-hanging fruit. “Action in cities comes in the form of public infrastructure customisation, generally of power systems and transport,” says Shreeshan Venkatesh, climate policy lead at Climate Trends, a research-based consultancy. While transport and power are undeniably top sources of emissions, the piecemeal approach of addressing them without locating them in the larger city plan or as part of the country’s net emission targets is hardly sustainable.

Comprehensive planning calls for immense coordination between many ministries – also between the centre and state or city governments – which means lateral coordination. Long-term strategies or Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which have to be periodically submitted to the UNFCCC, hinge on consultative processes between powerful ministries that handle environment, power, and finance (which looks at carbon market structures and financing mechanisms) each of which approaches Climate Change issues from its own perspective.

Legislation and policies in areas such as energy, power, agriculture, and water are either set out by the central or state governments or both. State governments usually decide urban development and infrastructure planning. But cities are where all this takes concrete shape. Unless city governments are heard and taken on board on climate action, translating COP commitments on the ground will remain a challenge. Also, cities in India are not financially or politically powerful unlike many international cities, says Ulka Kelkar, director, climate program, World Resources Institute (India). “The long-term signalling must be reflected in cities’ plans.”

Photo: Shalini Singh

Indian government at COP27

The India pavilion was situated close to the main or blue zone entrance, marked by a diorama of a gurgling water body and several power transmission lines, invoking the Apah Suktam (water deity hymn) from the Rig Veda alongside the government’s LiFE (lifestyle for environment) campaign plastered on the walls. The Suktam is to be expected from a government that focuses on Hindu traditions in its functioning but the LiFE campaign displayed the government’s mindset towards tackling Climate Change.

Bhupendra Yadav, India’s Minister of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, elaborated on the idea in his blog post: If “one billion out of eight billion people adopt environment friendly behaviour like not wasting food, global greenhouse emissions can be reduced by 8-10 per cent” and called upon individuals to make contributions such as “take stairs, use bicycles, reuse resources, turn off power when not needed, eliminate daily use plastics…”

At best, these actions by a small section who can afford to adopt them in India’s cities become token individual actions in the face of a socio-economic system built on consumption that depends on coal and carbon-based mega infrastructure. As leading climate activist and researcher Soumya Dutta pointed out, “People’s choices do not change world economies. Telling citizens, ‘You be simple, you reduce’ won’t help if we are investing in carbon-intensive infrastructure, for example. Systemic issues made into individual issues just fool people.” At worst, the focus on individual action is a copout by the government as it shifts the onus to the consumer – last in the line of decision-making.

Even as the government makes the case for individual action, there are questions about what local governments can and should do, and how ecological sustainability and social equity would feature in their plans and actions. As India commits to lower emissions on the international stage, climate action must not perpetuate the existing structures of inequality in her cities. Should there be a Loss and Damage Fund for communities within the country, set up by the Government of India and accessed by cities to buffer the most vulnerable who bear the brunt of climate events such as floods and heat waves?

India did not put down targets or commitments at COP27 unless as part of the UNFCCC consensus mechanism like the Long-Term Strategy which was required. The Indian delegation gave broad areas, no timelines. The seven areas under its Long Term-Low Emission Development Strategy are: energy, transport, urban design, industrial sector, carbon capture utilisation and storage technologies, enhancing forest and vegetation cover, low carbon development. How cities will implement these demands urgent and engaged attention.

From global to local

The Loss and Damage Fund points to an urgent issue in the Climate Change discussions: Funding or climate finance. India cannot hope to get much from the Fund even when it’s up and running because of the conflict – it is projected as an economic power but per capita emissions are among the lowest. There was a coordinated strategic push at the COP27 to dilute and move away from the term “developing” to “major economies” or “large economies” or “countries with capacity” – a move that analysts believe will eventually hurt India. Large developing countries that have high cumulative emissions, prominently China and India, are being pushed to commit to higher ambition on both emissions and finance. This is an increasingly contentious issue and is set to escalate. Given the current global economic conditions, where the climate finance for cities comes from is likely to become more contentious.

What does the COP27 mean for the vulnerable people in cities? An international event like this is not useful unless the gap between the ‘ground’ below and ‘sky’ above is bridged. Delhi, for instance, has suffered acute air pollution every year but drew up a state action plan to combat Climate Change only earlier this year. Mumbai has its plan but there are questions on its implementation. “Delhi as a signatory to the Paris Agreement, has committed to reducing 50 per cent sectoral emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. It’s working to electrify 80 per cent of its bus fleet by 2025 while setting up appropriate EV charging infrastructure for public transport vehicles,” says Reena Gupta, advisor, Delhi government. Transport is only one area that needs to be tackled; there are others.

“There isn’t a standard template or gold standard for climate action factoring in political realities,” says Venkatesh, “No one wants to disrupt the political arena. Pollution is one area on which there is consensus but, even then, big emission cuts are difficult to implement politically. Equity and justice need to be at the centre of plans. How much one emits is also a class-based division in a country like India.”

The other aspect to note, Aarti Khosla, founder, Climate Trends, pointed out, was on mitigating emissions from the agriculture sector. “India called (at COP27) emissions arising from agriculture ‘survival emissions’ distinct from luxury emissions in richer countries. India did not succeed in removing the mitigation language entirely – although negotiators managed to have it watered down substantially – bringing national and local circumstances as key determinants of how climate action would be carried out within the agricultural sector.”

Photo: 350.org Creative Commons

Biodiversity and climate action

On the morning of the biodiversity-themed day at COP27, I took in the clear blue sky above and pristine aqua Red Sea below at the beach. Guiding me was Amir, a young banana farmer from Qena and a lifeguard who handed me a snorkelling mask and words of encouragement. In the ocean, floating close to a steep coral reef were brightly coloured fish of varying shapes and sizes, and flora bobbed up and down, as the sun’s golden rays danced off the water. I shut my eyes to imprint the image on the mind, and thought: What if folks in suits were to hold Climate Change negotiations under water or in open green forests instead of in artificially insulated cabins over coffee and cola?

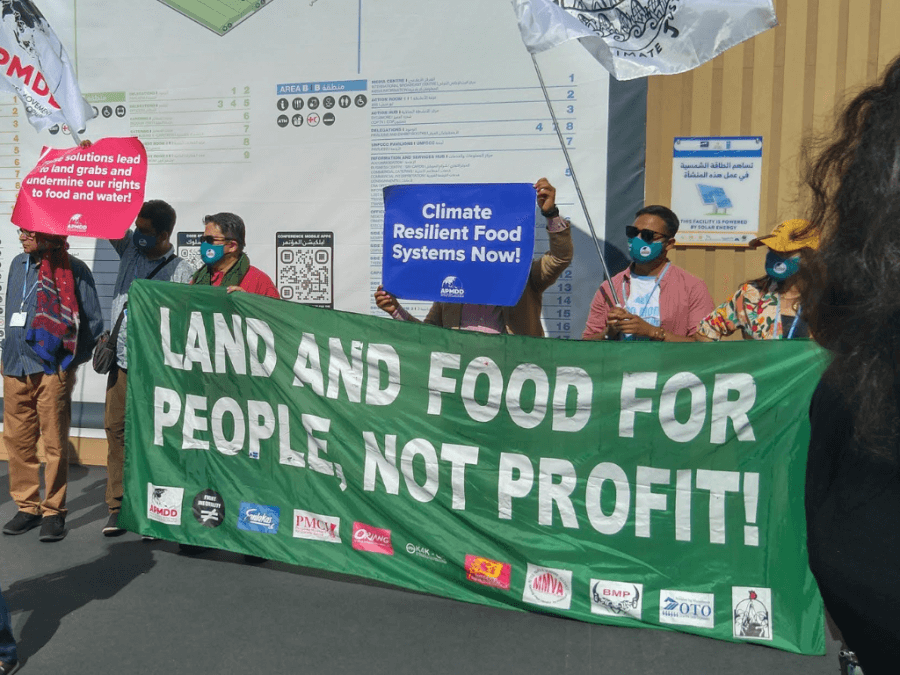

Dichotomy built into the conference template is not limited to nations-and-cities. On the gender-themed day groups from Africa and Asia screamed slogans such as “Food and land for people, not for profit” at the designated corner of the COP27 venue; just about 100 metres away, in a closed hall, a session had important women occupying important seats to words such as “including women in business is good for business.” Protesting voices become tokens but they are important riffs in an orchestra that otherwise plays predictable tunes. At the COP27 entrance, people in cow and rabbit costumes handed out vegan cookies and pranced with banners on the virtues of vegetarianism; an old Canadian with a long white beard held forth on ‘Sustaina Clause’, and some indigenous groups sang songs in their languages.

This is the Climate Change conference ‘business as usual’ mode but everyone wears the right shade of green now. The talk on the global stage is over, it is for leaders in cities around the world to get down to the brass-tacks, the nuts and bolts, of how to secure climate funding and translate climate action on the ground. There are no easy paths here.

Shalini Singh is a Delhi-based journalist and co-founder of People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), which did a nation-wide series on Climate Change supported by the UNDP. Singh reported on Climate Change based on the lives and views of the farmers and fisherfolk of the Yamuna river in Delhi. She attended the Conference of Parties (COP27) at Sharm el-Sheikh in November.

Cover photo: Gerry Machen/ Creative Commons

There is 1 comment

Beautifully covered. Highly informative.