Upon the different forms of property, upon the social conditions of existence rises an entire superstructure of distinct and peculiarly formed sentiments, illusions, modes of thought and views of life.

Thus wrote Karl Marx in his essay “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon” in 1852. A hundred and seventy years later, this insight continues to hold relevance in the context of Chandigarh. It would not be too far-fetched to claim that Chandigarh has consolidated private property and privilege in the post-independent India. Chandigarh was the city conceptualised and driven by the State to fashion a new kind of citizen for the post-colonial Indian democratic republic. This is ironic, yet instructive in that it forces us to question Indian urbanism, who cities are built for, and how they shape our modes of thought.

One of the greatest challenges for post-colonial Indian urbanism was to break away from deeply-rooted social pathologies such as caste and colonial mindsets which encouraged class and race-based segregation. Modernity was embraced as a panacea. However, despite its proclaimed democratic and egalitarian foundation, Chandigarh today appears as a city designed for neo-liberal India. Its grided hierarchy, segregation of functions, and wide tree-lined avenues are magnets for attracting capital – but excluding the labour class.

Chandigarh’s sector-based plan aims to eliminate “disorder” – only prescribed activity and legitimate residents can occupy space in these “containers of family life.” The self-contained unit isolates and insulates the residents of one sector from another such that each sector constitutes its own reality. The size of plots in a sector determines the social class of residents there and the inward-looking plan of a sector ensures that residents are isolated from reality other than their own. There is not much by way of a shared experience of the urban life.

This should not come as a surprise as Chandigarh’s planner, Le Corbusier, saw successful urbanism as a profit-making venture. He outlined his idea to administrators thus: “Buying of necessary land….selling of first plots…arriving of the first inhabitants…a phenomenon is born: it is the appreciation in the value of a piece of land. A game, a play has begun. One can sell cheaply, or at a high price. It depends on the kind of tactics and the strategy employed in the operation. Good urbanism makes money. Bad urbanism loses money.”

Since rising land values were – and are – seen as a sign of successful urbanism and Chandigarh was to be a “self-financing city”, the only people considered as “legitimate” residents of the city are those who are financially able to make such transactions. Citizenship in Chandigarh, therefore, translates to ownership of property within the planned grid.

Life in and outside the grid

What is it to live in independent India’s first planned city? The answer would vary greatly on where one lives, particularly if one inhabits the grid or lives outside it. Do you live in your own house in one of the northern sectors, in government housing for mid-level employees, as a tenant in a paying guest accommodation, or in an incrementally built precarious house outside the grid?

Most people would defend it as a beautiful city. Architects, planners and administrators did not just build Chandigarh; “they produced a discourse.” To re-emphasise Marx’s words, Chandigarh’s plan has encouraged “peculiarly formed sentiments, illusions, modes of thought and views of life.” The hegemony of the celebratory discourse has not left much space for the lived experiences of its diverse inhabitants to be heard. Also, its poor have internalised the “City Beautiful” discourse to such an extent that it remains the only way to discuss the city regardless of their own experiences.

Photo: Rishabh Mathur/ Flickr

The periphery and the peripheral

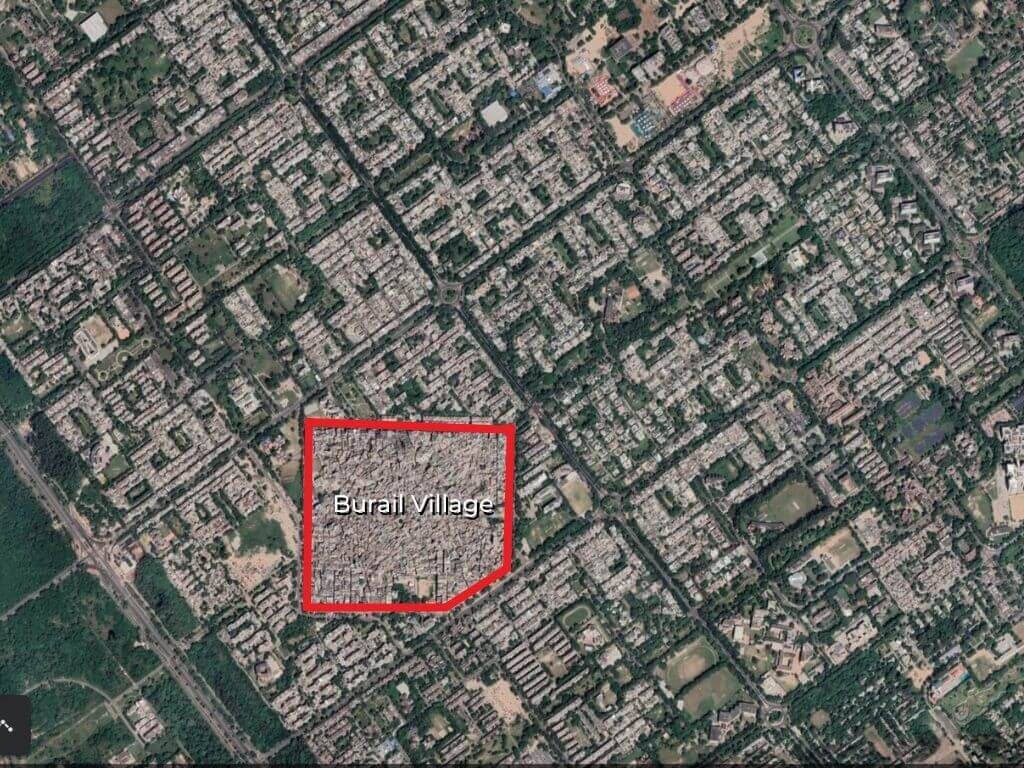

In the elite consciousness of the city, the idea of a “slum-free” Chandigarh appears normative. Since the city, particularly the first phase, has fortified itself using preservation and heritage as its tools, all newer developments are pushed to the periphery or the peripheral (the unplanned areas within the grid).

There is no denying that Chandigarh is a city of the State, by the State and for the State. Intended as a capital for Punjab, it now houses the governments of the Union Territory, Punjab, and Haryana. It is arguably the most surveilled city in the country with cameras and police personnel dotting every street intersection. Yet, it is in the crevices of the state spaces, in its fringes and its cracks, that life finds a way.

In the initial plan, a radius of 5 kilometres around the grid city was demarcated as controlled zone with agrarian or forested landscape. In 1952, the Punjab Assembly passed the Punjab New Capital (Periphery) Control Act and later expanded the greenbelt to 10-kilometre radius. This was intended as a buffer around the Modernist Chandigarh clearly highlighting its break with the past. It also romanticised the villages surrounding the city, imagining their future as fixed in time, but overlooked the possibility that they would undergo rapid transformation.

This transformation began as soon as Chandigarh was announced. In village Bijwada, adjacent to the land acquired for the first phase of the city’s construction, a new economy emerged to cater to construction workers, supervisors and government officials involved in city building – small shops for daily needs, furniture makers, and cotton ginning for quilts and mattresses. Bijwada was eventually incorporated into Sector 23 of Chandigarh and a modernist order imposed upon it. Like this, 17 villages were bulldozed to create the Tabula Rasa for the city. Such obliteration was successfully resisted in the second phase; much of the Lal Dora area was accommodated as aberrations in the plan. Those who could not afford the planned sectors, including low-level government employees such as chowkidars, gardeners, drivers settled in the peripheral zones.

Photo: Google Earth

The Act was to ensure that villages outside the masterplan, within a radius of 10 kilometres, retained their agricultural character. For Le Corbusier, this greenbelt was a buffer so that suburbs would not develop and land speculation would be discouraged outside the planned urban core. A restricted zone outside the grid would enhance the value of land within it. The rural surroundings were crucial to his plan as they framed his masterpiece with the mountains as the backdrop.

It is important to note that the central government first violated the sanctity of the periphery when several large defence projects, including the 385-acre campus for the Cantonment of Chandimandir, were built. Soon, an airforce station, the HMT factory, and Terminal Ballistics Research Laboratory followed. In 1966, the restructuring of Punjab meant that the periphery was under the jurisdiction of three governments. Only about 3 per cent remained with Chandigarh, the newly declared Union Territory; Haryana and Punjab respectively controlled 22 per cent and 75 per cent.

Both Haryana and Punjab built their townships adjacent to Chandigarh in the periphery; Punjab extended the Chandigarh grid onto Mohali (SAS Nagar) and Haryana developed a fan-shaped Panchkula alluding to Albert Meyer’s plan for Chandigarh. Wanting to piggyback on their real estate success, surrounding villages such as Zirakpur, Naya Gaon, and Kansal became hubs for haphazard, private player-led development. The hierarchies of the grid city of Chandigarh have extended beyond its boundaries.

The skyrocketing real estate prices in Chandigarh mean only the super elite can afford it; Panchkula and Mohali act as interim zones where the upper-middle class have built single family homes or purchased high-end apartments. All others make do with precariously constructed apartments in Zirakpur or tentatively legal land in Kansal.

Chandigarh too incorporated Manimajra village into its boundary and, more recently, developed the area behind the lake into an IT park. In the interstices of these zones, Chandigarh’s elite bought farmland to build elaborate farmhouses. The rush to capitalise on land in the periphery led to a massive real estate project initiated in the Sukhna wildlife sanctuary with 95 MLAs as beneficiaries. This was shelved in 2019 after the Supreme Court ruled against it.

The rigidity of the masterplan, among other factors, meant that Chandigarh’s periphery became the frontier for unchecked urban growth. It is also the site of the story of Chandigarh’s labour.

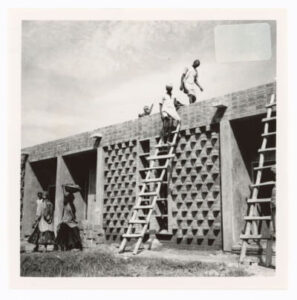

Photo: Fonds Pierre Jeanneret, Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture

Photo: Jitesh Malik

Labour colonies: Reading a demolished archive

Anything of value must be produced by human labour; so it is for cities. It is also undisputed that human labour occupies space. Yet, time and again planners of cities have failed to account for the large number of construction workers. Despite the claims of Chandigarh’s planners and administrators that the city would provide housing for the “poorest of the poor,” the plan had no place for its labouring populations, even though construction workers were a vast majority of Chandigarh’s early inhabitants.

An estimated 30,000 women and men laboured to give shape to the city’s masterplan during the first two years. They were commented upon and often orientalised by architects. Le Corbusier remarked at a conference in Paris in 1953: “The picturesqueness of the Indian enterprise is extraordinary; women in ‘saris’ carry bricks on their heads, the men lay the bricks; the children play in the heaps of sand. In India one does not ‘Taylorize’ the design to economize on about, since the population is innumerable. Everyone sleeps on the spot under a rush mat carried on four stakes. The gangs of workmen arrive from far with their families.”

The rudimentary shelters built by the construction workers for themselves are described in his own words and signal the emergence of the first labour colonies in Chandigarh. Most of these were in the vicinity of the work sites such as near the Capitol Complex. One of the largest settlements was near the Sector 22 site, adjacent to Bajwada village. Others came up near brick kilns and provided cheap bricks which allowed for low construction cost.

The first labour union in the city was registered with the support of the Communist Party of India in 1953 with construction workers constituting most of its members. The planned city of Chandigarh was thus made possible by the simultaneous emergence of the unplanned settlements in the city. During the initial phase, the growth of these unplanned settlements was much faster than the planned city. In that sense, the history of labour colonies is also the history of the building of Chandigarh – one that has never been told.

But space has a use value and an exchange value; the balance here tilted in the favour of the latter. The unplanned clusters of thatched houses were seen as hindering the aesthetics of the planned city. In 1958, the Capital Project Office issued notices to all unplanned settlements to remove their dwellings. Not surprisingly, this was met with resistance from the workers and the Capitol Workers Union organised a strike in November 1959 demanding alternative sites.

The construction of Chandigarh was in full swing. Recognising the need for labour, the estate office relented. “Temporary” sites were allocated in the then peripheral parts – in Sector 26 and the Industrial Area. Residents were allotted a plot each of about 15×20 square feet at a rent of Rs 1.50 per month. Since these colonies were temporary, the estate office did not consider it their responsibility to provide basic services.

Importantly, having moved them further away from the planned parts of the city, the estate office ensured that these people would remain invisible. This peripheralisation of labour that produces and reproduces Chandigarh has sustained even as various labour colonies and settlements were removed, demolished, and shifted as the city grew. The planned part of the city was to be only for those that were of a certain economic status – property owners, government employees, corporate professionals.

I tried searching for a map of Chandigarh that marked the labour colonies and unplanned settlements. Not surprisingly, the only one that I found was from around the time of the Covid-19 lockdown showing sealed zones and the densely populated areas.[2] The Chandigarh administration worried that these would become centres of the pandemic, and sealed them off from the planned city leaving residents inside the colonies to fend for themselves.

A fear psychosis usually permeates the elite consciousness about dense unplanned settlements. Urban governments appease the propertied class by demolishing slums/shanty towns/unauthorised settlements; Chandigarh is no different. Although labour colonies predate the city itself and most were built incrementally on land allotted and re-allotted by the government, they remain on the city’s periphery. Demolition drives have intensified. On May 1 last year, ironically International Labour Day, Colony Number 4 was demolished. The newspapers next day had a familiar headline “Chandigarh reclaims 63 acres of land worth Rs 3000 crores” with hardly a reference to 50,000 or more who became homeless.

The image of the Chandigarh aesthetic is so strong that even the sight of “disorderly” spaces cannot be tolerated. It would be fit to explain the hegemony of the elite in Chandigarh, drawing upon scholar Asher Ghertner’s work, as a “rule by aesthetics.” Left to their own devices, the people living on the periphery of the city serve as the labour pool to be harnessed for every new phase of construction, but ignored and invisibilised at other times. The story of Chandigarh needs to be retold from the perspective of the periodically shifting labour colonies which present an alternative archive narrating a subaltern history of the celebrated city.

Anu Sabhlok is Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), at Mohali. Her research lies in the areas of feminist geography, critical infrastructure studies, and labour studies. Her outreach work can be found at https://migrantlabourers.wordpress.com and https://sheharstudio.wordpress.com

Cover photo: Labour Colony number 4 bulldozed on the periphery of Chandigarh by Anu Sabhlok