On September 28, 1908, Hyderabad received a staggering rainfall of 12.8 inches in the first 24 hours, which soon snowballed into 18.90 inches of rain over a 48-hour timeline. It would devastate the city on a never-seen-before magnitude (100 millimetre or four inches today is ‘very heavy’).

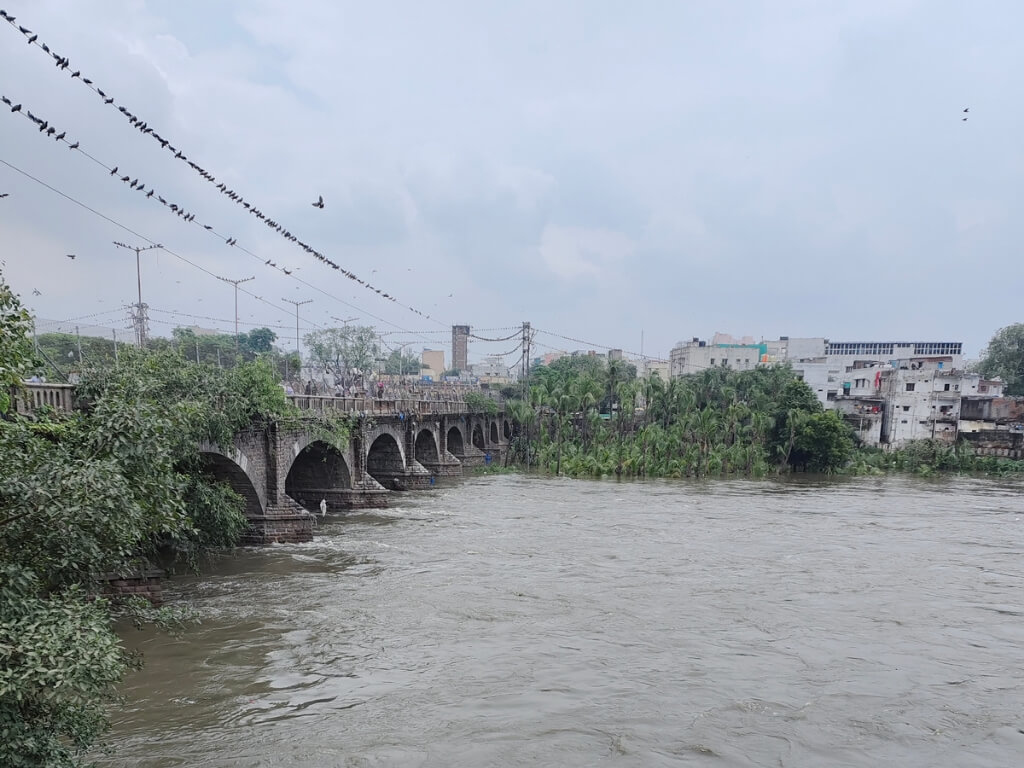

Called the Musi river floods, or the Great floods of 1908, it led to an estimated 15,000 deaths and destruction of around 65,000 buildings. A major reason behind the unforeseen calamity was that 221 out of 788 water tanks or beds abounding both the northern and southern banks of the Musi river (in the picture above) had flooded.

Hyderabad was founded by Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah in 1591 on the southern bank of the Musi, which used to flow across the city. Today, the river is a huge sewer as the government dumps the city’s sewage into it.

The city’s flood protection systems were designed by legendary engineer M Visvesvaraya in the 1920s. Yet, by rampantly destroying lakes and wetlands. it has failed to preserve the age-old system. Looking at the devastation over the years, the efforts of the renowned civil engineer seemed to have gone down the drain.

The solutions are the problems

The catastrophe hit Hyderabad during the rule of the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, Mahbub Ali Pasha. Later, his son and the last Nizam, Osman Ali Khan (1911-48), modernised Hyderabad to flood-proof the city.

The Hyderabad state, under Osman Ali Khan, set up the City Improvement Board in 1912. Sir Visvesvaraya was brought in as a consultant to save the city from flooding and to design a new and modern sewerage system. After carefully carrying out surveys, he suggested building storage reservoirs for “temporarily impounding all floods in excess of what the river channel could carry”.

Visvesvaraya’s autobiography Memoirs of My Working Life mentions there were 788 tanks in a basin of 860 square miles of the Musi River — one tank for every square mile of the catchment.

Those two dams that he proposed were named Osman Sagar (known as Gandipet lake) and Himayat Sagar, which today have a full-tank capacity of 45 million gallons per day (MGD). The city gets a supply of 462 MGD. Back then, the two reservoirs were enough but with the rising population, the demand is rising. Water is released through 32 gates of the two reservoirs when they are full as only excess water is released during heavy rains.

After 1948, the year when Hyderabad state was annexed to India, people slowly began settling or building homes on dried up river beds of the Musi river. Ironically, thanks to several encroachments over the decades, releasing water from the two lakes also floods an entire colony of people at Moosa Nagar in Hyderabad. Water released from the Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar — which defied the purpose they were built for — have become a threat for residents.

One of the areas facing flooding is Moosa Nagar, situated on the Chaderghat bridge (which is much lower), which connects Kachiguda and other areas to Hyderabad’s old city via Malakpet. At the edge of the bridge is an entire colony, which has been flooded and partially submerged twice since 2020.

“The Kirlosker committee submitted a decade ago, had clearly recommended that storm water drains/nalas to be clearly recommended that storm water drains/nalas to be widened for the free flow of rain water in GHMC limits. Totally 28000 illegal constructions on 173 Nalas/drains required to be dismantled which will be costing around Rs.15000 crores towards compensation. As such this matter was kept in abeyence by the Govt as heavy budget was involved,” mentions a paper, Heavy floods on the urban roads of Hyderabad flooding low lying inhabitants of Hyderabad metro city – a case study. [1]

Photo: Siddhant Thakur

July floods a repeat of 2020 calamity

Hyderabad received 125 per cent excess rainfall in July this year, with continuous rain wreaking havoc. The rain-battered city saw a repeat of the 2020 floods. As per data from Telangana State Development Planning Society (TSDPS), the city recorded large excess rainfall of 144.2 mm against the normal mark of 38.1 mm.

Imran Taj, a resident of Moosa Nagar, whose house was flooded during the July rains, plans to shift from the area. “The flooding this year was less severe compared to 2020. But, this time too, we saw a lot of destruction. We are planning to move from here because of this problem. The gates were open for two days and water kept coming in continuously. Before 2020, the gates had been opened only once when I was a child,” says Taj.

The effect of July rain this year was a repeat of 2020 flooding, although less severe. Houses were flooded; roads submerged; low-lying areas waterlogged; water dragged in sewerage and filth, filling up homes with muck and damaging properties. People spent days cleaning their homes. Like in all climate events the marginalised communities were the worst hit, and even the loss of a day’s wage adds to their struggle.

Architect and city planner Shanker Narayan has been living in Hyderabad since 1987, and he says he saw the city’s first major flood in 2000. “It is possible to prevent floods in the future, but houses which are already built are a political matter. The government’s focus is not on floods as the calamity happens once in a few years.”

Lakes turn real estate hotspots

Hyderabad’s several lakes are being encroached upon for decades as colony after colony has been built over water bodies.

Nagamaiahkunta and Nawabsahab Kunta are two such lakes. The word ‘kunta’ means lake, but there’s not a trace of water unless it rains. Another dense area that gets flooded regularly is Nadeem Colony and its surrounding areas in Toli Chowki, which have been built in the full tank level of the Shah Hatim Talab.

Situated in the Golconda fort area, the Shah Hatim Talab or lake is over 400 years old. In 2020, when Hyderabad was hit by heavy rains of around eight inches (the highest that year), many residents of Nadeem Colony had to move out as water entered their ground floor homes.

Sprawled over 100 acres earlier, Shah Hatim lake has now shrunk and what remains is an appalling 12 acres of the water body. City-based journalist Serish Nanisetti, who has written a book on Hyderabad’s foundations, Golconda history, and who has covered the city for around two decades, said, “Golconda Fort’s moat, which is almost gone due to encroachments, is surrounded by lakes, connected to the Durgam Cheruvu (in Hyderabad’s HITEC-City). The moat and the lakes were intrinsically connected and that protected the fort historically. One of those lakes connected to the moat is Shah Hatim talab, on which Nadeem Colony has been built.”

The middle-class residents of Nadeem Colony in Toli Chowki chose to buy land in an area built on the Shah Hatim lake’s full tank level and knowing that it gets flooded regularly. It is one of the worst-affected areas during heavy rains every year.

Most areas turn flood-prone

According to the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC), there are a total of 185 lakes in its jurisdiction. GHMC’s west zone, which has HITEC-City and where construction is rampant, also has the highest number of lakes at 82.

But, rampant construction and rapid urbanisation is a threat to the water bodies, which are fast disappearing. This coupled with extreme climate events has worsened the city’s capacity to deal with calamities.

Al-Jubail Colony in the Falaknuma area of Hyderabad’s old city, and Osman Nagar under the Jalpally municipality (outskirts) have been encroached upon the full tank level areas of two old lakes. It’s not surprising that the areas have turned flood-prone and residents worry at the slightest indication of heavy rain.

The marginalised communities who live in the two areas have been financially drained in the 2020 floods. Some had saved money to buy small pieces of land as investments, and many who were living on rent, pretty much lost all of their belongings. Photos of people using boats to move around for months after the floods showcased the extent of devastation and the apathy to tackle it.

While Al-Jubail Colony was flooded with water from the Palle Cheruvu, Osman Nagar was built behind the Shukoor Sagar. Water has not completely receded out of the areas, and problems of the people have multiplied. Fed up of the situation which has worsened even after repeated complaints to the authorities, most residents have started shifting out of the area.

While marginalised communities encroach upon lakes to build homes, builders eye old water bodies for new real estate ventures. Activists have been raising such issues, but action is hardly taken.

Photo: Siddhant Thakur

Guttala Begumpet lake ‘disappears’

The most recent case is that of the Guttala Begumpet lake in Ranga Reddy district, adjoining Hyderabad. On July 29, environment activist Lubna Sarwath mailed a complaint to the district collector, with satellite image proof, to show that the lake has disappeared.

The images show that between 2016 and 2022, buildings were built in the green areas of the lake but no action has been taken. It will not be surprising if those areas will get flooded like the Chikoti Garden locality of the posh Begumpet area where buildings mushroomed on marshes and small water bodies. “People will keep constructing new buildings and that is going to endanger lives,” said an activist, who did not wish to be named.

Urgent solutions the only way forward

Government officials admitted that many constructions are illegal, and that several lakes have been encroached upon. “If it is happening with the department’s knowledge, means there are more people behind this,” said one of them, without sounding alarmist. They said that only a strict policy decision can save water bodies.

A research paper, Rapid Assessment of The October 2020 Hyderabad Urban Flood and Risk Analysis Using Geospatial Data, spells out some solutions.

“…the October 2020 Hyderabad flood event and the resulting damage are an aggregation of climate change, changes in rainfall pat-tern, uncontrolled urbanization and land-use changes induced to anthropogenic activities. Since urbanization and climate change go hand-in-hand together, urban flooding and the subsequent damage will intensify in the near future. Therefore, to make cities resilient to urban flooding, we must adopt flood-mitigation measures, rejuvenate natural wetlands, upgrade the storm sewer drainage in tandem with future population-projected scenarios, adopting nature-friendly engineering solutions as an integral part of the smart-city planning.” [2]

According to Narayan, the government can make small changes in flood-prone localities. “In some areas, narrow streets get flooded due to walls that hold up flood water. There, the problem is the height and not the spread of rainwater. Some change can be made by removing obstacles that hold up water. As people continue to live in these areas, it is not possible to make them leave,” Narayan pointed out.

The urgency and willingness for the solution should be collective and merely chalking out policies without a strict implementation and people’s participation is futile as we see in all cities in the country. Most suggestions and recommendations are only on paper and the building laws which are in place are hardly adhered to — which is evident from the high-rises coming up on marshy land and wetlands. With experts warning that floods will intensify like other climate events, it’s time to act now.

Yunus Lasania is a Hyderabad-based journalist with a decade of experience in reporting issues in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. His deep love for Hyderabad and its history is showcased in his Instagram page, The Hyderabad History Project. He also hosts Beyond Charminar, a podcast series on the history of Hyderabad, focussing on the lesser-known aspects of the city.

Cover photo: Yunus Lasania