Neopolis, the new sub-city being constructed on the outskirts of Hyderabad, exemplifies the relationship between such cities and the climate crisis. Planned and built in the neoliberal framework where the state acts as a land broker and land is commodified, the 533-acre ‘city’ is yet another business district with an overwhelming 90 million square feet that’s coming up by flattening complex non-urban environment and modifications to natural vegetation, which compromise the natural ecosystem of the area. There are ‘climate signals’ in and around Hyderabad which Neopolis seems to ignore, as detailed out in this essay.

In June 2008, the Government of India launched the National Action Plan for Climate Change programme, which established a comprehensive strategy to adapt to Climate Change[1]

During this period, an Indo-German research collaboration on climate and energy took place in Hyderabad, one of the ten cities globally selected for this programme. This involved, from 2005 to 2013, institutions and scholars, representatives of state agencies, municipalities, and civil society organisations from both the countries.[2] With its primary focus being interconnected sustainability issues, including environmental and resource degradation, and innovations in institutional and governance structures.

Hyderabad’s transformation into a mega urban region was deeply intertwined with the climate challenges. The study identified climate-related signals and proposed adaptation and mitigation measures in sectors such as transport, food supply, urban and peri-urban land use, energy, and water provision.[3] It emphasised the need to understand how the process of economic development exacerbated pre-existing disparities among different socio-economic groups within the city. Climate Change, as is known, disproportionately affects the urban poor. A web-based participative tool called the Climate Assessment Tool for Hyderabad (CATHY) was launched which served to inform urban and transport planning, to avoid settlement planning in flood-prone areas, considering heat wave impact, designing ventilation corridors and shading, and planning transport routes that did not obstruct natural water flows.[4]

Photo: J.M. Garg/ Wikimedia Commons

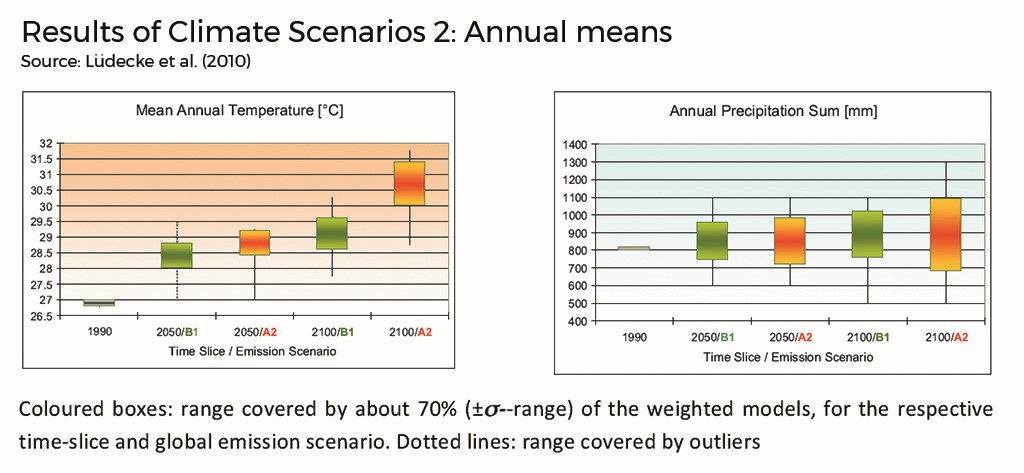

According to the project’s lead scientist Dr Ramesh Chenamaneni, this was the first time that long-term Climate Change implications for Hyderabad and the Deccan region were studied. These included projections which considered two scenarios based on global CO2 emissions: A high-emission (A2, business as usual) and a low-emission (B1, global emission reduction from around 2035). Two critical climate variables were identified – Intense monsoon rain events occurring once every two years with daily rainfall exceeding 80mm a day, and requiring preparedness for a 60 percent increase in frequency until 2050; and extremely hot days (more than 40 degrees Celsius in plains or 5 degrees Celsius exceeding normal temperature) which the city currently experiences 1.2 days per year to rise to 20 days till 2050.[5]

The Environment Protection Training and Research Institute in Hyderabad, in 2015, developed a State Action Plan for Climate Change (SAPCC) highlighting Telangana’s vulnerability, particularly of its river basins, industrial zones, and urban and rural areas. The report projected severe fluctuations in monsoon rainfall and varying intensity ranging from 2-14mm per day possibly leading to drought, and an average temperature variation ranging from 3.9 to 4.2 degrees Celsius. Besides other aspects, the report highlights food security and infrastructure vulnerable to climate-related issues.[6]

This discourse about the climate impact unfolded in parallel with development such as Neopolis, as if the latter was not concerned with the former. A key recognition was the vital role of public engagement, coupled with an awareness of the heightened vulnerability of the urban poor to the climate impacts. The response included proposals emphasising sustainable and resilient urban planning, transportation optimisation, and poverty alleviation strategies. This awareness and knowledge have been contradicted by subsequent actions such as the building of Neopolis which prioritised ‘decontextualised economic development’ inadvertently exacerbating the climate challenges and pushing a substantial population towards adverse consequences.

The predictions, projections, and considerations of climate continue to be absent from the urban planning process.

Laws exist, broken with impunity

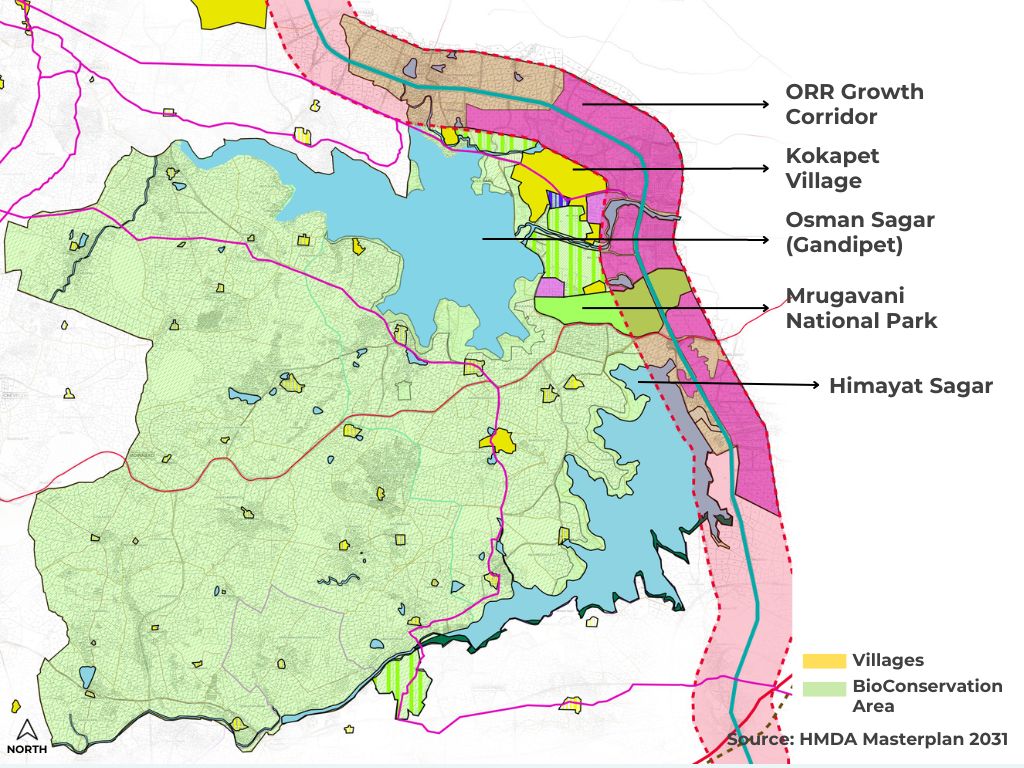

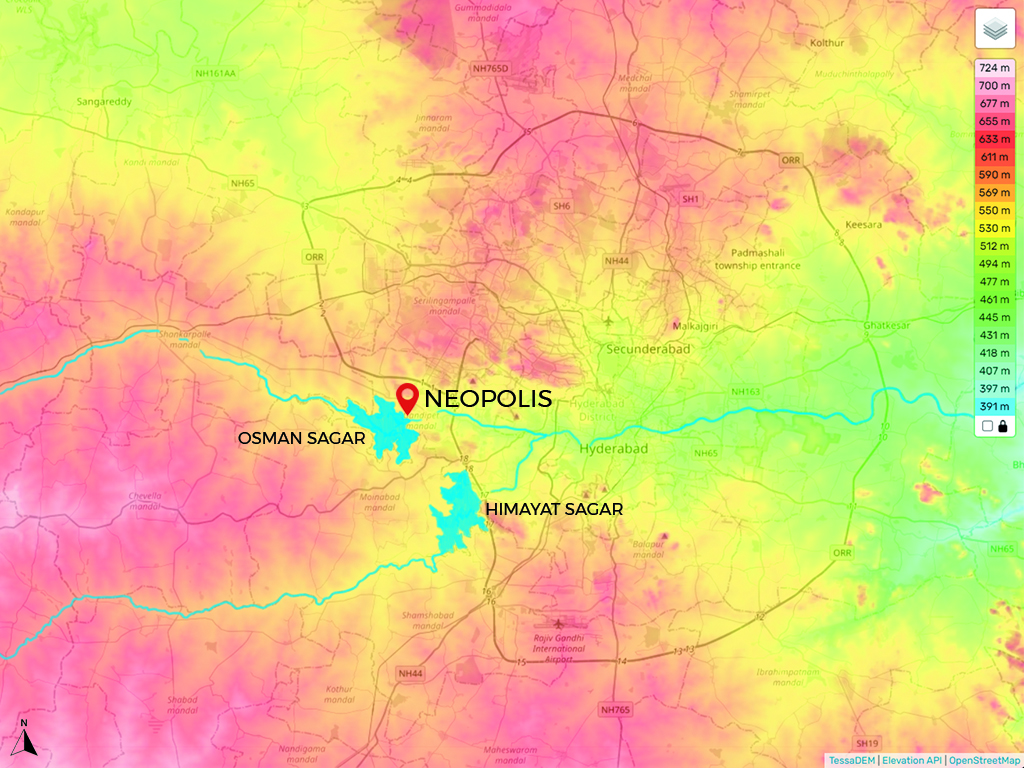

The making of Neopolis is at a critical juncture of cities emerging as primary contributors of emissions driving Climate Change. Neopolis lies on the full tank level of the Osman Sagar reservoir in the western peri-urban fringe of Hyderabad. A precondition to the auction of plots here was declaring the land ‘encumbrance free’ by circumventing the pending legal claims of ownership, and revoking the protective measure which saved the lake and its catchment area through the Government Order (G.O) 111 of March 8, 1996. As is known, the twin lake reservoirs of Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar were built to protect the city from floods in the river Musi which originates 100 kilometres away in the Ananthagiri Hills. The freshwater collected and stored downstream before entering the city became the source of piped water supply.

The justification offered to revoke the G.O is that the lakes are unable to meet the city’s water needs given that the water supply share fell from 27 percent to less than 2 percent as Hyderabad is drawing water from sources further away. For the first time in their history, both the lakes went dry in 2003 compelling the search for new sources of water. Several environmentalists claimed that the capacity reduction of the reservoirs was artificially created to justify the capital-intensive irrigation projects which came at a heavy cost of new infrastructure development and energy consumption. The state claimed that if the lakes are not supplying water, it is no longer necessary to protect the catchment or the reservoir.[7]

The justification around the G.O largely ignores the flood mitigation mechanism initially built. As a result of the changing local weather patterns, the chances of experiencing once in a 100-year flood increases significantly. The unpredictability of frequency, intensity, and duration of rainfall makes it imperative to save the reservoirs and catchment areas. The consequences will first be on newer development which is likely to disrupt the network of flow before it inundates the city downstream. It is noteworthy that the building permits were issued before revoking the G.O, and regulating water in the tanks. The October 2020 flood led to the opening of floodgates of the Osman Sagar reservoir after a decade, submerging several low-lying neighbourhoods for weeks.[8] [9]

A number of lakes have either shrunk drastically or been built over in the past 20 years; those surrounded by residential areas became cesspools with untreated sewage released into them. The water streams have also been blocked, paved over or garbage strewn into them.[10] In 1973, there were approximately 934 water tanks in and around Hyderabad; in 23 years, a hundred had decreased, and around 18 water bodies larger than 10 hectares and 10 smaller tanks were lost.

Source: HMDA Masterplan 2031

The relative ease of obtaining permission for new layouts and buildings in the new liberalised system makes matters tougher as the Town and Country Planning Department prioritises timely permissions – within three weeks – over due diligence. There is also the regularisation of buildings and layouts built before 2018 without verifying how many of these are in low-lying areas, river banks, lake beds, streams. In addition, a new regulation waives off building permissions for plots smaller than 75 square yards and offers instant approval of buildings in plots of 600 square yards. The local topography is changed by blasting, breaking of rocks and changing contours, water flow patterns make any mapping exercises on vulnerability inaccurate and unreliable.

There are activists who call for all encroachments to be demolished and natural state restored, but they fail to acknowledge that this would worsen socio-economic inequity. Another missed facet of this debate is the untreated sewage released into the Musi, combined with the slow and steady stream of water, irrigates farms along the river banks and becomes food of the city – a public health disaster.

Source: Topographic-map.com

The G.O 111 is preceded by another from 1994, G.O 192, that calls for protection of the ‘hydrological regime’. Telangana has the likelihood of two droughts in five years, which affects the water supply, agriculture production and livelihood;[11] and indirectly the food security, apart from affecting soil moisture and groundwater levels. In 2008-10, the low rainfall led to a substantial decrease of 23.61 percent in food grain production.[12]

The G.O 111 protected 1,32,000 acres of combined catchment area of the twin reservoirs and 84 villages inside them. It also prohibited the building of industries in 10-kilometre radius upstream and downstream, and within 500 metres of the full tank level, besides regulating open land and minimum built areas. Additionally, it protected the outflow channel of the reservoirs such as the Balkapur and other interconnected channels. Also, a 30-metre buffer zone was identified on the streams and construction activity prohibited; a similar buffer was enforced around the Mrugavani National Park, the forest area between the two reservoirs.[13]

Source: Kulsum Nafis

A two hundred and fifty ‘Neopolises’

Despite all this, rampant encroachments and frequent land use conversions have led to a reduction of 300 acres in the area of the lake.[14] The new international airport is built on the catchment of the Himayat Sagar reservoir; 2,000 acres of the Hyderabad Airport Development plan falls in the bio-conservation zone of the Master Plan for 2031. Additionally, as this researcher observed, there is construction activity, stone crushing, and quarrying operations besides road construction projects, tree felling, and breaking of hillocks in the area.

Recent actions to ‘preserve’ the lake, such as Mission Kakatiya, a state programme, started a campaign to “Save Gandipet’ which is another name of the Osman Sagar reservoir,[15] are clearly contradictory. They involve fencing the entire lake area, disconnecting it from its catchment, and impeding its natural water flow by constructing cycling and pedestrian paths. This is a step towards privatisation and commodification of the lake, given the proposals to create a Disneyland-like park in its vicinity.

To reiterate, the location of Neopolis is not incidental but a carefully determined site for the demonstration of the city’s global ambitions. The revoking of G.O 111 would mean an estimated 250 copies of Neopolis, driven by the same profit-oriented capital-intensive projects to generate revenue for the state. The creation of the highly paved park on the banks of the lake, and the beautification drive already points in that direction.

A recent study by WRI India on the impact of urbanisation on natural infrastructure states that the inefficient management of land use in India resulted in 85 percent more conversion of land compared to the population it supports. It asserts that there is limited research on how newer developments impact the natural infrastructure, ecological and hydrological systems. The natural infrastructure in cities is a buffer against climate-driven extreme weather, and therefore an important adaptation and mitigation resource.

The campaign ‘Save our Urban Lakes’ has been rallying to save the reservoir to protect the city from flooding. It recently released ‘A Scientific Report on Repeal of G.O 111’ incorporating a list of suggested measures for the protection of the lake, and associated livelihoods.[16] Considering the location of the city in the semi-arid region and experiencing climate variability further intensifying drought and affecting food security, it cannot be viewed through the lens of only protecting the lake from pollution or as flood protection mechanism for the city. It has to carefully address the watershed planning and management of the river Musi, associated agricultural land and livelihoods, and offer natural infrastructure to protect the city from climate-related events.

Climate through Neopolis’ lens

In conclusion, Hyderabad’s urban planning trajectory is directed towards a neoliberal logic with the role of the state shifting from policy maker and regulator to an active participant in the economic process. The neoliberal state sees the urban environment purely through an economic lens; its policies and practices reflect this. A discussion of the impact of urbanisation on Climate Change has to consider the specific mode of urbanisation such as Neopolis. From its conception and creation, physical location, branding and marketing, to the form of its built environment as it is currently taking shape all point to where a built environment is being created for the purpose of profit. Its impact on climate has to be understood from the standpoint of this economic logic.

The story of Neopolis in Hyderabad is not unique; similar developments can be observed across India. The closest in scale is in Mumbai, where the development of a coastal road and new urban enclaves in its erstwhile docklands follow a similar developmental logic as that of Neopolis. The loss of peripheral wetlands in Kolkata and Chennai, lakes and river systems in Bengaluru, and the growth of privatised urban enclaves on the periphery of Delhi are also outcomes of the neoliberal urban policy and planning on climate and ecosystems.

The already damaging effects of Climate Change, whether as extreme weather events or long-term changes in temperature and ecologies, require urgent and appropriate mitigation initiatives from states and institutions. The climate-cities relationship can be made sustainable and resilient through a focus on construction practices, housing and transportation policies, local food networks, regulation of polluting infrastructure, and the reduction in both waste and resource consumption.

However, the logic of the neoliberal economy is focused on generating surpluses primarily through over-consumption and intense resource extraction. In this context, a city developed primarily for economic purposes cannot respond adequately to climate crises. Responses such as planting new trees, beautifying lakes, or constructing non-fossil fuel-based infrastructure cannot mitigate the underlying cause which is the development of land for new profits. The only solution, therefore, lies in shifting the policy framework that governs urbanisation and new urban developments to build resilient and just cities, balancing environment and development.

Arshiya Syed is the founder of an architecture and urban design firm Studio Maqam in Hyderabad, Deccan. She is a graduate from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, and an Urban Fellow from the Indian Institute of Human Settlements in Bangalore. She is also a visiting faculty conducting urban design and housing studio in architecture schools.

This is the second and concluding part of her essay supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia.

Cover photo: View of the ongoing destruction of the Deccan landscape. Photo: Arshiya Syed