“We shouldn’t be concerned about trees purely for material reasons; we should also care about them because of the little puzzles and wonders they present us with. Under the canopy of the trees, daily dramas and moving love stories are played out. Here’s the last remaining piece of nature, right at our doorstep, where adventures are to be experienced and secrets discovered. And, who knows, perhaps one day the language of trees will eventually be deciphered, giving us the raw material for further amazing stories.”

With these delectable words urging us to see trees in a new light, as life forms that feel and communicate with other trees around them, that say something to us if only we cared to listen with attention, German forester and author of international repute, Peter Wohlleben wraps up his fabulous book The Hidden Life of Trees. In 36 small chapters, he takes us through the many dimensions of trees that only a person in love with trees can, blending research and studies with gentle humour and persuasion, bringing science to masterful storytelling.

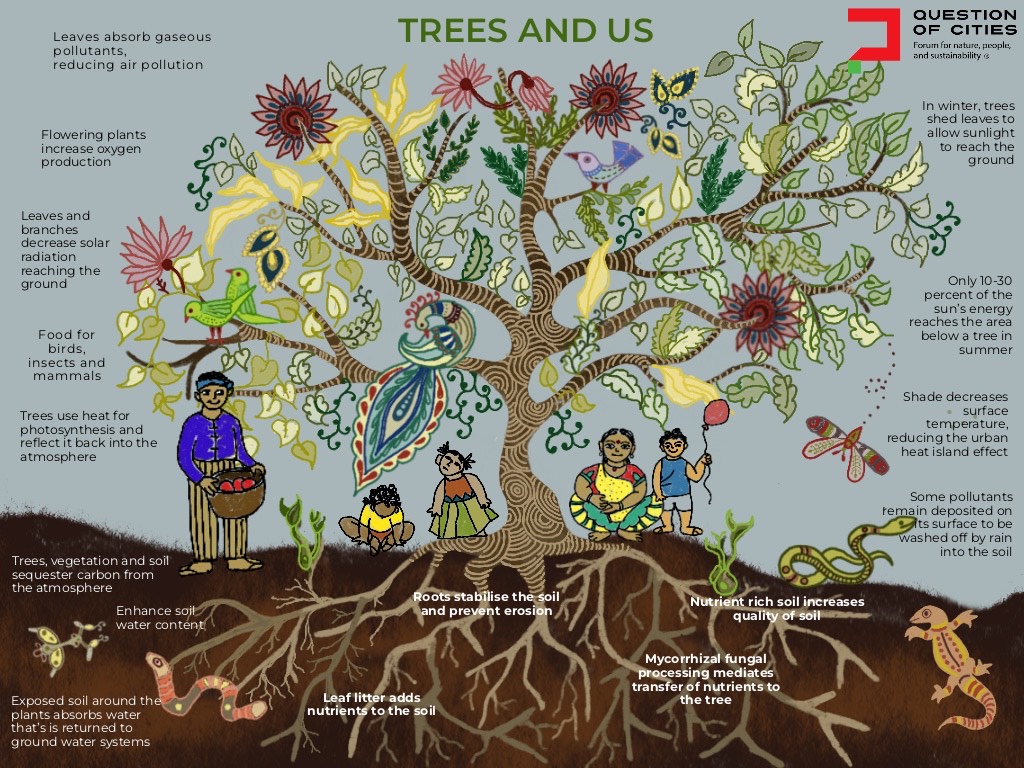

Wohlleben succeeds, in great measure, because he tells stories from the perspective of trees and compels us to join him on the journey. It’s an important and enlightening journey. And it goes well beyond the predominant way we see trees – as service providers to us humans with their shade, flowers, fruits, and barks. Or as performing ecological functions such as trapping water and sustaining the groundwater levels. As beings that hold down soil and make other life forms possible, as carbon sinks and climate mitigators that are so essential in the era of climate change, as home to hundreds of insects, birds and animals that form the complex web of life. The stunning illustration by my colleague Nikeita Saraf brings this to life.

If trees could communicate, what would they want us to know? Wohlleben takes the “if” out of the question and simply asks what trees communicate to us. It’s a tantalising question that forces us to think beyond the ecosystem services that trees provide and see trees for themselves, the beings they are. Do they feel love, can social security be a concept about trees? How do they age? What does it mean to shed leaves in a certain season and how do they know seasons? Do they have character and, perhaps, etiquette? How do they weather the storms, literally and figuratively? Can they really bloom wherever they are planted?

In his insightful introduction to the book, Indian environmentalist and filmmaker Pradip Krishen writes about the Indian Sal tree (Shorea robusta) and the puzzle about its habitat. One of the greatest timbers in the world, the Sal was grown across western Uttar Pradesh and Bengal through Odisha and parts of Madhya Pradesh. “…all through the second half of the 19th century and beyond, the Indian forest department tried with conspicuous lack of success to grow Sal in new areas outside its native range…They failed again and again, and could not surmise why.”

Then, drawing on anecdotes and studies, Kishen provides the answer to the puzzle about the “gregarious” Sal. “It has always been known that you can’t grow a Sal tree on its own. You won’t find a Sal tree growing in a park, for instance. Foresters tell us that Sal trees die of ‘loneliness’ when they are planted singly…When the Wildlife Institute of India in Chandrabani, near Dehradun, was built in the early 1980s, its main building was situated in a cleared Sal forest. One by one, Sal trees that became isolated started to die. These ‘lonely’ trees were clearly dying because they had lost communication with the rest of their group but how on earth did they know or sense this? What was the mechanism that enabled a sal tree to keep in touch with the rest of its gang? Was it chemical – scent? Were they communicating underground through their roots?”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Their work, their words imagined

The root network of trees is, indeed, where the magic lies. This makes it possible for the trees to be what they are, do what they do, and communicate what they want to. They convey chemical substances to the tree and to other roots – an entire ecology exists below the soil – but the question is if it also contains impulses akin to electrical impulses in human beings triggering, perhaps, a human brain-like activity. If roots have been proved to change direction when they find toxic soil or stones, it could be seen as an ‘intelligent’ response to an unexpected situation. Assuming that through this ‘intelligence’, trees communicate to us, here’s what they might want us to know.

That they, naturally and unassumingly, sequester the carbon we emit through their leaves and vegetation to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere which contributes in a major way to global warming, contributes to wildfires, and leads to floods among other extreme weather events. Carbon sequestration improves soil health and climate resilience. But tree lovers would go beyond to understand that the leaves and branches, or the roots which are the most long-lasting part of trees, must also be storing their experiences of weather fluctuations, human contact, and attacks.

They would want us to know that they unceasingly absorb the pollutants in the atmosphere and literally clean up the air we breathe. The harmful ozone, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and other emissions that would hang in the air are absorbed by trees through tiny pores in their leaves called stomata while Particulate Matter collects on leaves.[1] Tree lovers will go a step beyond these services trees provide to explore what happens to them when they clean up after humans.

“The climate can also change so severely that it falls outside the range the trees can tolerate. And because they have no legs to carry them away and nowhere to turn for help, they have to adapt so that they can deal with the situation themselves,” writes Wohlleben, “The first opportunity to do this comes at the very earliest stage of life. Shortly after fertilisation, when the seeds are ripening in the flower, they react to environmental conditions. If it’s particularly warm and dry, appropriate genes are activated (of the European beech).”

Adaptation is not something only human beings are doing to address climate change; trees have been silently but resolutely doing it for years. In the climate change time, they must adapt faster besides doing more emissions cleaning work for us. How do we compensate them? By chopping them down, irrationally trimming branches, cementing the earth where their roots start and so on. If only they could speak our language, they might have told us how ungrateful humans are. Yes, tree collapses have tragically taken human lives – like the latest one in Mumbai where one woman died and another was injured[2] – but trees falling have a lot to do with unscientific trimming and pruning, cementing the tree base and weakening its roots.

Then, trees would want us to know that they not only unhesitatingly provide food for birds, insects and humans but also enrich the soil that they live in by allowing their leaf litter to decompose into soil nutrients. Just as they absorb heat in summer, they generously shed leaves in winter so soil is protected from the harsh cold. By extension, this means that when we axe trees, we also hurt the soil and the on-ground environment that would have evolved and matured without human intervention over a long period of time. The soil is alive and trees keep it so.[3]

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Tree lovers recognise other functions such as the thick bark of old trees becoming a natural home to birds and bats who need that insulation, fungi that locates itself in pecked barks, and organisms moistening the wood fibres which are then used to make musical instruments. Trees are, as Wohlleben, calls them “motherships of biodiversity”. They meet various biotic (human) and abiotic (pollution) challenges. If we appreciated the deeply interconnected web of life, we would see that trees and soil are not detached from us, nor are people superior to them.

Trees would want us to know their roots network, an ecosystem in itself, that lies beyond our sight but not our perception. Roots not only stabilise the soil and prevent its erosion but also nourish and sustain a complete cycle of life beneath it – a colony of bacteria, algae, fungi, yeasts, and protozoa; invertebrates like earthworms, roundworms, and motes; vertebrates like groundhogs and mice as well as reptiles, frogs and insects.

Their network of fungi, or mycorrhizal networks, connects individual trees and plants together through fungi; this, Wohlleben eloquently termed, the “wood wide web” like our worldwide web. Most tree lovers respect the fruit-to-root cycle as well as the root ecosystem for itself. Those who do, are enriched. As the British writer-broadcaster on nature and culture, Richard Mabey remarked: “To be without trees would, in the most literal way, to be without our roots.”

Climate warriors, our allies

If we could understand the language of trees, we might learn that they can be our allies – even guardians, shields – as climate-related extreme weather events roil every part of the world. It may have contributed to the raging wildfires in Los Angeles due to “high winds and drought making vegetation dry and easy to burn”,[4] to the torrential floods across India including in Wayanad and Gujarat, and unprecedented snowfall in Saudi Arabia’s Al-Jawf region in November followed by torrential rain this week.[5]

The importance of trees, as natural buffers in a climate uncertain world, has been repeatedly underscored. Greener areas are less likely to flood – as trees reduce flooding – have better air quality and are naturally cool. Big trees protect smaller plants and shrubs by acting as a physical barrier from the surge of floodwater; their trunks, roots and branches block and change the direction of flow, slowing the speed of flood waters.[6]

On intense and high heat days, trees become climate warriors by helping to considerably cool the area they are in. Does this not carry meaning after 2024 turned out to be the hottest year on record? During heavy rainfall, trees as climate warriors absorb water into the soil and help slow down the runoff and reduce flooding. The lingering air pollution in cities might have eased if the tree cover was sufficiently thick enough for leaves to absorb the pollutants.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The impact of climate change can look different based on our address and socio-economic profile; the poor are the most vulnerable during climate events and find it harder to resume their lives. In the reams of discussions about climate resilience, widely seen as engineering projects to ‘build’ the resilience, trees are often overlooked though their role as climate warriors is diverse and manifold. As climate change worsens, we need trees more than ever. Trees, and green cover, cannot by themselves address climate change challenges but are an indisputable part of the climate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

However, in seeing them as our climate warriors, we go back to valuing them for their usefulness to us. They are, indeed, climate warriors but it would be more prudent to see them as allies in taking on climate challenges. This is because climate change affects trees too. If only we could understand the language they speak, they would tell us exactly how. Scientists and arborists are our next best bet.

“Over the past century, in the temperate regions of North America[7] and Europe,[8] trees have shown a faster growth rate, up to 77 percent higher than in the previous century. At first sight, faster growth could be interpreted as higher biomass production, which would lead to a higher carbon storage capacity and, therefore, a greater contribution of our forests to the fight against climate change. A study by the Technical University of Munich[9] found that as the growth rate increased, the density of the wood dropped by eight to 12 percent, their carbon content decreased by about 50 per cent. This suggested that the trees extracted less carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” found scientists writing in The Conversation.[10]

If we paid attention to the trees and plants around us, attempted to understand them and their world, respect and marvel at their life cycles and ecosystems, the sense of wonder about nature might return to our jaded and city-deadened senses. As Wohlleben laments: “The main reason we misunderstand trees is that they are so incredibly slow. Their childhood and youth last ten times as long as ours. Their complete lifespan is at least five times as long as ours. Active movements such as unfurling leaves or growing new shoots take weeks or even months. And so, it seems to us that trees are static beings, only slightly more active than rocks…It’s hardly any wonder that most people today see trees as nothing more than objects.”

Smruti Koppikar is a Mumbai-based award-winning journalist, urban chronicler, and media educator. She has more than three decades experience in newsrooms in writing and editing capacities, she focussed on urban issues in the last decade while documenting cities in transition with Mumbai as her focus. She was a member of the group which worked to include gender in Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 and is the Founder Editor of Question of Cities.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf