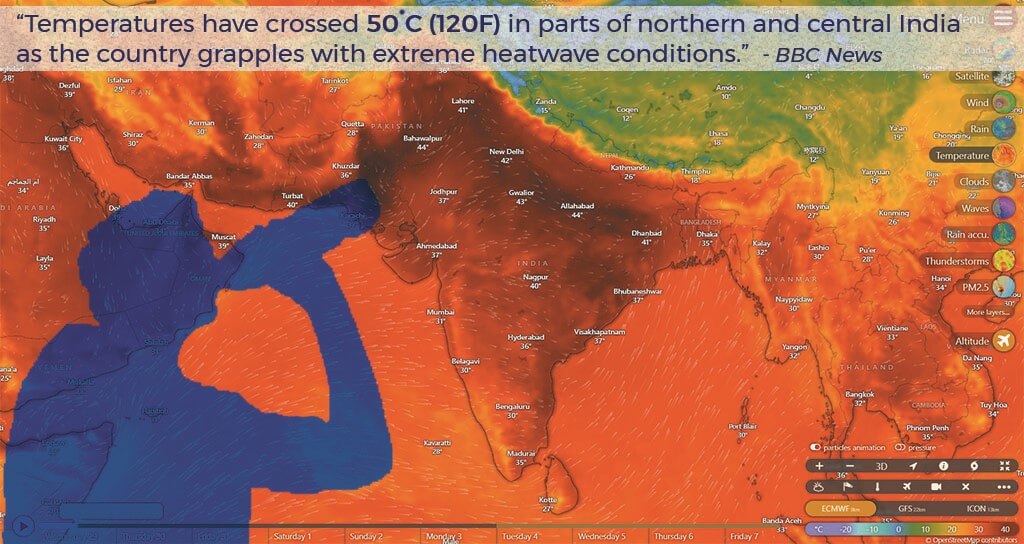

On May 29, Delhi recorded its highest-ever summer temperature at Mungeshpur at 52.9 degrees Celsius; the following day, a worker died in his tiny tenement without a fan while an overworked air-conditioner caught fire in another area of the capital. It capped a continuing phase of weeks of extremely high temperatures across north and northwestern India as Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh saw earth-scorching temperatures in the mid-to-high 40 degrees Celsius – an average of 8.5 degrees Celsius over the normal.

In ten of India’s hottest cities in this region, the average temperature on May 29 was over 46 degrees Celsius. In the previous week, the Consumer Dispute Redressal Forum in Delhi recorded the extreme heat thus: “There is neither air-conditioner nor cooler in the courtroom. The temperature is more than 40 degrees Celsius. There is too much heat…it is difficult to hear arguments.” April and May, in which millions were also out in the heat to vote in the Lok Sabha elections, have seen extreme temperatures in other states too, including in the northeast.

The heat wave followed high temperatures in the last two years. The India Meteorological Department (IMD) had warned on April 1[1] about an abnormally hot summer. This has brought into sharp focus the need for Heat Action Plans (HAPs) that are comprehensive, dynamic, climate-adaptive and localised. Question of Cities is calling for critical and urgent conversations among governments, policymakers, and the media on HAPs.

The extreme heat in India is not an anomaly. Globally, April was warmer than in any previous April going back to 1940, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service.[2] In fact, May 2023 to April 2024 have been warmer than any previous 12-month period at 0.73°C above the 1991-2020 average, it pointed out. Releasing the latest report from World Weather Attribution,[3] scientist Friederike Otto stated: “From Gaza to Delhi to Manila, people suffered and died when April temperatures soared…Heatwaves have always happened. But the additional heat, driven by emissions from oil, gas and coal, is resulting in death for many people.”

Scientists at WWA showed that extreme temperatures in south Asia are now about 45 times more likely and 0.85 degrees Celsius hotter due to climate change. The link between extreme heat and climate change has prompted many to call this a climate emergency. It would be catastrophic for millions of people if the emergency is treated as a passing phenomenon.

Instead, it should become an opportunity to recognise:

- That heat, especially extreme heat and heat wave, is a natural disaster on par with urban floods, earthquakes and so on covered under the Disaster Management Act 2005[4]

- That it is imperative to prepare and implement HAPs in every city and district of India, and within them, focus on the most vulnerable areas or “hotspots” and groups of people

- That heat and heat waves have to do with the kind and pace of urbanisation adopted across the country[5]

- That heat waves, like air pollution and urban floods, have a symbiotic relation with the green cover and trees in cities

Heat Action Plans so far

Having localised HAPs with clear strategies, action points, and a chain of command is now critical to the lives and livelihoods of millions, especially those who live or work outdoors. Almost 323 million across India are at high risk from extreme heat and a lack of cooling equipment, found this UN-supported report.[6]

India’s first strategy to beat the heat was in Odisha in 1999 after a crushing heat wave took thousands of lives. The first city-based HAP was implemented in Ahmedabad in 2013. So far, 23 states and more than 200 cities and districts[7] have HAPs in some form; many have been critically reviewed too. Broadly, based on reviews and discussions with domain experts, HAPs can be grouped into three sets – those prepared earlier which need to be upgraded and made climate adaptive now, HAPs that are ready but not implemented due to lack of mechanisms or other factors, and states and cities that have not drawn up HAPs or have only vague plans to combat heat.

Based on what the Parliament has been informed, HAPs are to establish an early warning system and inter-agency coordination to alert people and agencies about predicted high or extreme temperatures; to raise public awareness and disseminate information about heat waves using different media; to build capacity in healthcare including of paramedics and community health staff to respond to heat-related medical issues; and to collaborate with non-governmental organisations to implement measures such as publicly accessible drinking water and cooling spaces, night shelters and so on.

An assessment shows that while HAPs reduced heat-related deaths and illnesses, they suffer from “implementational deficits”[8] including a lack of coordination, communication and outreach gaps, and inadequate response. Other reviews have found that most HAPs had one or more of these lacunae: over-simplified approach, overlooking the local context, not focusing on most vulnerable groups, lack of funding, and the absence of government mandate.

“Heat plans have spread to several jurisdictions nationwide and they urge a healthy mix of different solution types – from infrastructure and nature-based solutions to behavioural adjustments. However, most plans do not account for local context, are underfunded and are poor at identifying and targeting vulnerable groups,” observed Aditya Valiathan Pillai, associate fellow at the Centre for Policy Research in India, who co-authored a critical review.[9]

Credit: QoC photo

Conversation and action points

Given this, Question of Cities identified 10 conversation-action points:

Augment public information: Experience shows this is central to people saving themselves from heat-related illnesses, even fatalities. Verified and timely information of expected heat waves should reach people as alerts on their mobile phones – as health warnings did during Covid-19 – and through all available media including advertisements on local radio and announcements on public address systems. Mobile phone alerts about extreme weather are routinely used in other countries – Dubai residents got such alerts before the deadly storm in April while Americans regularly receive warnings of extreme weather with a reminder to stay indoors. India’s colour coding of heat alerts has helped but these should reach every mobile phone in advance of a heat wave.

Recognise heat-climate change link, grow more trees: HAPs address heat as an isolated climatic phenomenon but studies have shown the inexorable relationship between extreme heat and climate change. Ideally, HAPs should be part of climate action plans which have comprehensive measures for all extreme events and hazards especially as the duration, intensity and frequency of heat waves are set to increase. “Humanity has less than three years to halt the rise of planet-warming carbon emissions…current policies are leading the planet towards catastrophic temperature rises,” warned the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2022.[10] Two years later, HAPs are yet to incorporate climate change aspects.

Photo: Avinash Chanchal

HAPs must be proactive, not reactive: HAPs emerged as a response to extreme heat taking lives; their four aspects are, therefore, reactive. For example, what should be done when temperature rises beyond normal. But a long-term climate adaptation strategy has to be proactive, addressing factors such as conserving trees and green areas, renewing water courses, limiting construction density, prescribing construction materials more suited to local climate, and linking the extreme weather to urban development itself.

Limited impact, uneven implementation: While HAPs helped decrease heat-related deaths where implemented, mortality is the endpoint of a long process in which other decisions have to be made. These include dynamic decisions such as keeping people indoors as temperatures rise, changing work hours, providing public-access cool shelters and drinking water, keeping gardens and parks open throughout the day, priming immediate medical care and so on. Without these as Standard Operation Procedure, HAPs remain limited. The purpose should be to keep all people safe and healthy in extreme heat rather than merely prevent deaths. Also, the implementation has been uneven across the country and within states too.

Go local, map area-based heat profiles: The more granular the plans, the better. Researchers have shown variations in heat in different parts of cities and districts.[11] While national guidelines are welcome, HAPs must be city or district-specific factoring in local humidity levels, wind directions, heat wave patterns and so on. Every city or district HAP must map hotspots within its area, draw up local heat profiles for areas, understand how Urban Heat Island works in each, and find out the threshold temperature for heat-related illnesses. Most HAPs lack such localisation but the way forward includes ward-level mapping and heat profiles.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Focus on vulnerable people: As with place, so with people. HAPs must identify vulnerable groups factoring in socio-economic differences within cities and districts which lead to differences in people’s capabilities to withstand heat stress. In high-heat zones of a city, poor people in congested dwellings, without access to cooling solutions are more likely to take ill during heat waves than people of better socio-economic status. Mapping socio-economic status along with heat-profiling areas is needed. Disregarding climate trends, local heat patterns, and socio-economic factors have made HAPs static in nature, reviewers pointed out.[12]

Talk Heat Index: The IMD’s definition of heat wave[13] based on surface air temperature could be insufficient given that India has varying humidity levels and wind directions which exacerbate it. Many countries use the Heat Index – combining air temperature with humidity and other conditions – to arrive at an accurate estimation of how hot “it feels like” to people. India’s efforts to develop a Heat Index must be speeded up and this reading, usually 4 to 10 degrees hotter[14], needs to become the norm.

Mandate HAPs, include in urban plans: An important lacuna is that HAPs are not mandated as part of the statutory government processes. As guidelines, government departments are neither obliged to implement them nor can be held accountable for tardy action or inaction, as happened in Delhi. In fact, all climate action plans must be statutory plans. The next step should be to weave them into urban planning instead of adding them as a top layer to urban plans. Cities must be planned and built in not only climate-resistant but nature-based ways. Nature-led urban planning is the way forward.

Capacity building beyond hospitals: The government-led strategies and measures to combat heat (and floods) will have to draw upon the resources of non-state actors such as public institutions, private organisations, corporate establishments, civil society groups and NGOs, and so on. While the onus is on hospitals – public and private – to prepare to treat heat-related illnesses and emergencies, governments must clarify what roles others can play before, during and after heat waves – or any extreme weather event.

Photo: Flickr

Chain of command, data and funding: Typically, most HAPs are located in medical and hospital departments of local and state governments to contain mortality and limit fatalities, but this is limited. The chain of command needs to be wider and clear – which department is responsible for reacting in real time to IMD forecasts, who turns them into alerts for people, who disseminates information within how much time, who alerts hospitals and other establishments, and so on. Increasingly, Heat Officers are being appointed – Dhaka was the first Asian country to appoint a chief heat officer last year.[15] Mumbai’s municipal corporation has set up an environmental and climate change department.[16] But unless their roles and remits are made clear, this only adds to the multiplicity of agencies. Data is important; heat-related illnesses and fatalities are not always recorded. Similarly, funding for implementing HAPs is a critical factor and governments must make budget allocations.

According to the Union Ministry of Earth Sciences, India’s average temperature has risen by 0.7 degrees Celsius between 1901 and 2018 and will rise by 4.4 degrees Celsius by 2100 while heat waves will multiply by a factor of two or three. In 2015, Indian meteorologists analysed summer high-temperature days in two time frames – 1969-1990 and 1991-2013 – which included data from 25 cities and found that “there has been a significant increase in the number of high-temperature days across India…and megacities experienced a sharp increase in summer high-temperature days during the second period”.[17]

HAPs are offered as a panacea. However, they must be climate-adaptive, localised with area heat profiles, focused on vulnerable hotspots and people, with adequate funding and a clear chain of command – and include tree planting and preservation as the bulwark against heat.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons