As cities grapple with alarming numbers on the Air Quality Index and official action to curb bad air is tardy, people suffer. Lives are upended, daily schedules are disrupted, and illnesses rise making air pollution a silent killer. Doctors have expressed alarm at the multiple ways in which air pollution is worsening people’s health. They concur with the studies which show that air pollution can take years off people’s lives.

The Air Quality Life Index report[1] reveals that people of Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan are expected to lose an average of around 5 years of their life expectancy if today’s levels of pollution persist. Shockingly, the report points out that in the last decade, 59 percent of the world’s increase in pollution has originated from India alone. People whose lives and livelihoods depend on being outdoors have no option but to face the brunt of the deteriorating air quality. They are forced to make do with masks or face income losses.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

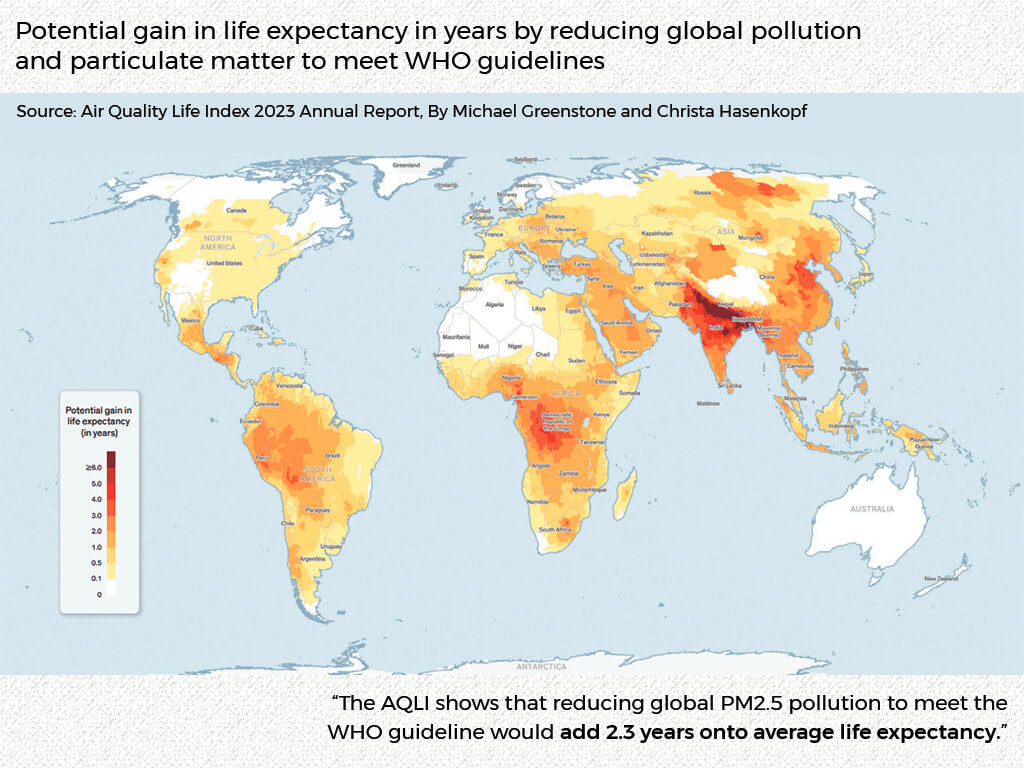

In the last decade alone, studies showed India bears a “disproportionate burden of respiratory diseases.”[2] Several studies examined the adverse effects of air pollution on humans, with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD),[3] asthma, Type 2 diabetes,[4] reduced lung function and implications in pregnant women[5] topping the list. On the other hand, permanently reducing global particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution in accordance with the World Health Organisation’s guidelines can add up to 2.3 years to the average human life expectancy.[6]

Here are a few voices from doctors, experts and the affected people on the effects of pollution that needs to be taken more seriously.

Source: Air Quality Life Index Report 2023

‘We are shocked by the rising AQI levels’

Dr. Mukesh Sharma, Professor of Civil Engineering at IIT Kanpur. He has contributed to preparing the national Air Quality Index and air quality standards in collaboration with the Central Pollution Control Board; he is also a member of the WHO Technical Advisory Board.

Pollution can be from exhaust and non-exhaust emissions. That from chimneys of power plants, industries and tail pipes are exhaust emissions while pollution from road dust, worn down tyres and other particles from roads are non-exhaust emissions. In addition to this, India burns its waste, there is crop/stubble burning, and vertical mounds in landfills also can catch fire which we do not account for. All of these contribute to air pollution at the city level, peri-urban level and rural level.

There’s photochemistry, or chemical reactions that happen under the influence of visible and/or ultraviolet light. Chronologically, when gases are released, they travel a certain distance; between their release and travel, a photochemical reaction occurs producing Particulate Matter which we recognise as pollutants. However, the source is elsewhere, in the gases released earlier.

I believe that finding solutions to control air pollution at source is the best strategy and preventing it at source is better. While improved technology is important, we also need to look at behavioural changes at a smaller scale. This is key to combating air pollution. We can bring in the best of technology but unless our practices change, there cannot be lasting improvements.

The short-term health effects that I see are coughs, common cold, tiredness and sickness because of outdoor air but there is also the ‘indoor sickness syndrome’ or conditions caused by being in an enclosed air-conditioned space for a long time. People feel uncomfortable, have headaches and difficulty concentrating; they feel better as they step out and breathe in fresh air. Short-term exposure takes a toll on our health over the years.

The common long-term exposures can cause asthma and COPD, but there are studies now connecting diabetes, arthritis, blood pressure and cancer to polluted air. When particles of metals enter our bloodstream, they could cause cancer; they are deposited in our organs which, though flushed out, retain some amounts over long years. However miniscule, in the long-term, these deposits are toxic to our bodies.

As for cost-effective measures in cities, there are short-term and long-term measures. Some examples of good long-term measures currently in place include the decision to introduce BS6 engines, improving the quality of fuel we use, and stringent rules for industries and power plants. In the short-term, cities can work on small-scale managerial issues which, when compounded, can have a significant impact. These include paving road shoulders, tackling traffic congestion by reducing the amount of time a vehicle is on the road, better recycling and disposal of municipal solid waste.

We developed the AQI as a mathematical formula to convey air quality in the simplest way – with one number and denoted colours. When we made the scale, we stretched it only to 500 because we thought that was the worst case scenario; we never thought we would see the levels (800 and 900) today. Simultaneously, we also developed air quality standards by looking at the health effects of different pollutants at different concentration levels and deciding the acceptable level of pollution with respect to health risks. A ‘safe’ concentration level is agreed upon, considering all possibilities of background pollution as well as a consensus from many stakeholders. An ‘acceptable’ risk of long-term exposure is also discussed – we generally accept one in 1,00,000 which means that one person, over the period of 40-50 years of exposure, is at the risk of having an illness.

The extremely high AQI levels are new to us which means there are not many studies linking them to health effects yet, but such hazardous levels are extremely worrying.

Photo: Mahesh Idupulapati/Wikimedia Commons

‘Air pollution is a national emergency’

Dr Sanjeev Mehta, Chest Physician and Pulmologist at Mumbai’s Lilavati Hospital & Research Centre, and at Arogya Nidhi Hospital

Breathing in bad air takes years off your life, there’s no escaping this. Lately, I have been seeing a lot of patients with nasal discharge, blocked nose, burning eyes; exposed surfaces like skin become dry, leading to skin problems. Lingering cough is a major issue which I see even with fairly healthy people. Asthma and COPD patients, who are vulnerable, are at a higher risk because the attacks reduce people’s immunity, which makes them more susceptible to viruses, causing more infections — it’s a chain reaction.

News reports say PM2.5 is the worst but I don’t make the distinction between PM 2.5 and PM 10 and PM 5 – they are all harmful. Yes, PM 2.5 is the one that can get into our bloodstream easily but PM 10 also deposits on our lungs. Why differentiate between two bad things?

I conducted an experiment testing the lung function of our hospital nurses and was shocked to find out that young, healthy people had poor lung function. Many children now have asthma, pregnant women and newborns also have health issues. As many as 65 million Indians have COPD — this is almost the population of France or the UK. Bad air is an epidemic in cities that people are not taking seriously. India has more people suffering from asthma than China.

Living in a polluted city takes years off your life. People are fatigued, there is loss of productivity and hence, loss of income, especially to those most vulnerable. There is a decline in mental health too. People born today are probably going to die 20 years earlier than usual.

Air pollution is a national emergency, in my opinion. We need long-term planning; currently mitigation measures are short-term and seasonal. We can’t only talk about pollution during four months of the year, it is too little, too late. This is a war that has to be fought over years – not something you or me or the government can deal with for a few months.

‘Mumbai’s polluted air forced me to shift to Goa’

Mamta Kalambe, 33, photographer and expressive arts facilitator

In October, after the monsoon subsided, one day the smog levels in Mumbai were very high and the next day, I woke up with a sore throat. This happened again, right before Diwali. I developed a cough and had to take medicines but it lasted for more than two weeks. I have moved to Goa and one of the main reasons for the shift is the pollution. I don’t have any of these pollution-related problems now.

But whenever I visit Mumbai, my throat turns sore. And, the first thing I check is the AQI to see how bad it is and what I can expect. Winters bring in more health problems – it could be a sore throat or blocked nose or something else. The AQI in Mumbai is better during the monsoon only.

I am not a smoker, I follow a healthy and good lifestyle, so it is really frustrating when I face health issues because of the polluted air.

‘I felt my chest tightening when the AQI shot up in 2016’

Soumya Dutta, climate change and sustainability activist, also member on the board of several independent organisations advocating climate solutions

I have had an asymptomatic heart issue for years which almost never interfered with my hectic activities and adventure sports. In 2016, when I was 58 years old, the AQI in New Delhi, where I spend most of my time, went beyond 600 and continued to be severely high for days. That’s when my heart issues turned critical, my pulse rate fell to 37-38, and within a month and a half, I had to get a pacemaker installed.

Doctors attending on me said bad air could be a possible cause but it would be difficult, in the absence of concrete studies, to state that air pollution was the cause of my health issues turning grave. What seems to happen is that polluted air turns existing ailments grave.

The impact of air pollution is manifested more strongly on those with pre-existing heart and lung issues, and on young children and the elderly. When my health issues aggravated, I felt my chest tightening around the time that the AQI went up in 2016 and I have felt it every year since. There is also difficulty in breathing and a sharp drop in my energy levels. When I go out of Delhi to places with cleaner air, these symptoms reduce sharply or simply vanish.

‘230 cities in India are severely polluted’

Avinash Kumar Chanchal, 32, Campaign Manager (Climate and Energy), Greenpeace India

We, in Greenpeace India, have analysed the AQI in almost 300 cities across the country for years and have found that more than 230 cities are so polluted that they do not meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standards. No action plans to combat air pollution have vulnerability studies to assess its impact on people’s health, especially that of the marginalised sections of the population.

None of the existing action plans have a socially or an economically just solution. Pollution advisories on the days with poor AQI impose blanket bans on construction and industrial schedules, but that does not extend to how workers are impacted by air pollution both in terms of health and economics. These people do not get wages or compensation for such missed work days while they are dealing with polluted air and its impact outside. So, they bear it both ways.

‘Street vendors, rickshaw drivers, waste pickers impacted the most’

Sandeep Verma, 38, Delhi Convenor, National Hawkers Federation

I have been living in Delhi for the last two years and have fallen sick frequently since I moved here. The last time I developed a cough, it took four months to cure.

No matter which city we look at, people who are directly in contact with bad air suffer the most. Street vendors, rickshaw pullers, waste pickers are on the streets at all times and are impacted by pollution. Their families too are impacted because often they are the sole breadwinners. I have seen pollution have such a deep impact on vendors that a 40-year-old person looks like 60 years old.

Recently, a young shop keeper had chest pain and he fainted in the shoe market. He was hospitalised for 3-4 days. He only knows that he has to work to support his family. Street vendors have to deal with the police, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi while trying to run their business. They can’t be bothered by climate change issues. Many street vendors are homeless and spend the nights on the roads, increasing the impact that bad air has.

Photo: Sumaira Abdulali/Wikimedia Commons

‘Whatever needs to be done to reduce pollution needs to happen soon’

Kusum Lata, 37, makes sanitary napkins for an NGO

We are getting diseases that our elders did not have and that is probably because of air pollution. My mother-in-law, my children and I have problems breathing every time we step out. Our eyes tingle and burn.

Pollution levels are high in Delhi but those incharge of making the change call it normal. Through Greenpeace Foundation, we have approached the government to resolve the problem of air pollution but to no avail.

Even if we want to cycle, the city does not have cycling lanes or parking areas. Cycling plays a huge role in climate action. We’ve also had unseasonal rain over the last few days. Whatever needs to be done to reduce pollution needs to happen soon.

My husband, 38, who is a driver, falls sick often. He has a cough and his eyes burn all the time. If he takes a day off, his pay is cut. The doctor told him that the air in the city is not suiting him. But we want to live in the city. What will we do back in our village?

‘My coughing bouts are endless and it’s frustrating’

Mohammad Sabir Ansari, 35, food stall owner in Adarsh Nagar, Delhi

I have been living in Delhi for the last 20 years and I have a cough for at least 10 months of the year since the last eight years.

I have to keep getting myself checked for illnesses like TB because I am also an activist, which requires me to be among people. I suffer from a bad nagging cough; once my coughing bouts begin, they are endless. I need to maintain the highest levels of hygiene because I deal in food. But my shop loses business worth Rs 2,500-3,000 a day when I am absent from the shop, which is huge when counted over months and years.

I am frustrated because the cough makes it difficult for me to eat well. The intensity of coughing bouts makes me vomit solid food. Regular gym and kung-fu training has helped me somewhat. I have become so sensitive to polluted air that I start coughing even if someone lights a cigarette around me. When I go to my hometown in Jharkhand, I don’t have any cough or breathing problems. On the train back to Delhi, I start coughing the moment we enter Ghaziabad.

The city’s pollution is not changing so I am planning to run my own farm on land that I have recently bought in Jharkhand.

Cover photo: Pollution tracker installed in the Taj Mahal to track declining AQI.

Credit: Justin Morgan/Creative Commons