The Right to Environment, embedded in the Right to Life in Article 21 of the Constitution, has to mean clean air and water, and adequate open space, at its most fundamental level of interpretation. As cities across India expand at the cost of natural areas, and often without protecting the ecological integrity of a place, the degrading quality of air and water is the first casualty.

In August this year, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution to recognise the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right, and called upon all stakeholders including governments and businesses to “scale up efforts” to ensure such an environment for all. The resolution noted that this Right to Environment is “related to other rights and existing international law,” and stressed that multilateral environmental agencies should work under the principles of international environmental law.

As the Conference of Parties (COP) ends its 27th edition, the focus is on the Loss and Damages Fund to be set up by the wealthier polluting nations to enable the poorer and less polluting nations to grapple with the impact of urbanisation on environment, acutely exacerbated by the Climate Change impact. Notwithstanding the developments on the fund, it is imperative that nations such as India focus on setting right environmental mistakes at home; fixing polluted air should be the top-most priority for the central, state and local governments given that bad air claims millions of lives every year and more than a dozen Indian cities rank in the list of the world’s most polluted ones.

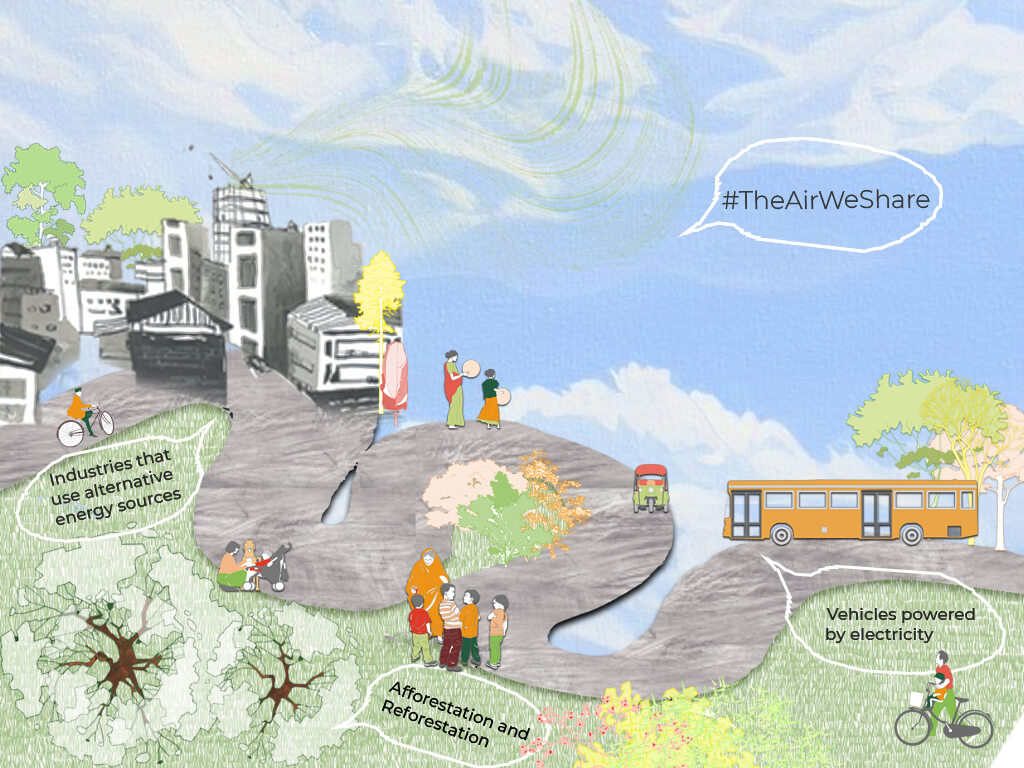

As we set about repairing the damage done to our natural resources, especially air and water, it is crucial to acknowledge that even in cities we depend on the natural environment as much as the built environment. In 2019, the UN declared September 7 as the International Day of Clean Air for blue skies. This year’s theme, #TheAirWeShare, draws attention to transboundary air pollution.

The Right to Environment includes the right to clean air, of course. Living with polluted air has proven to adversely affect people’s health and even reduce life span or lead to death. India’s rapid urbanisation, with an unnecessary binary between economic development and environment protection, has meant 14 cities with the dubious distinction of being in the list of the world’s top 20 cities with worst air pollution.

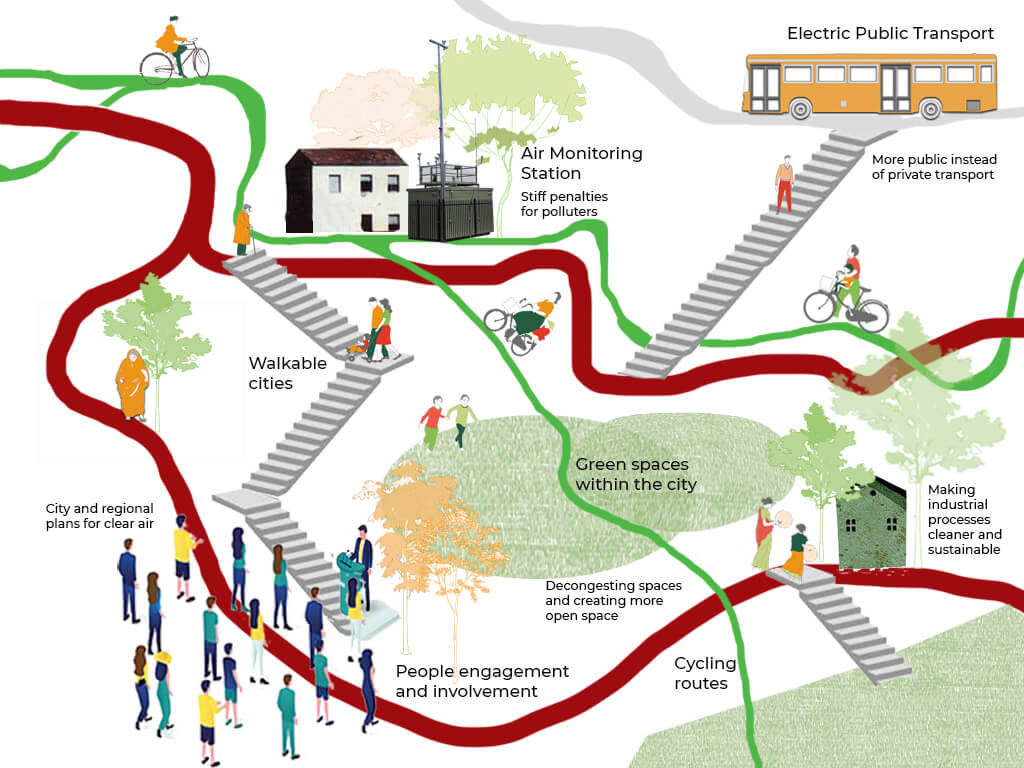

The need to address air pollution and have clean air was acknowledged however, in cities such as New Delhi, which is among the worst polluted cities in the world consistently over years, the shift from using fossil-fuel based transport to cleaner energy sources began more than a decade ago. Both the government – central and local – as well as the Supreme Court have reflected on the issue and taken steps. The process of cleaning the air is complex and tortuous; the outcomes are slow.

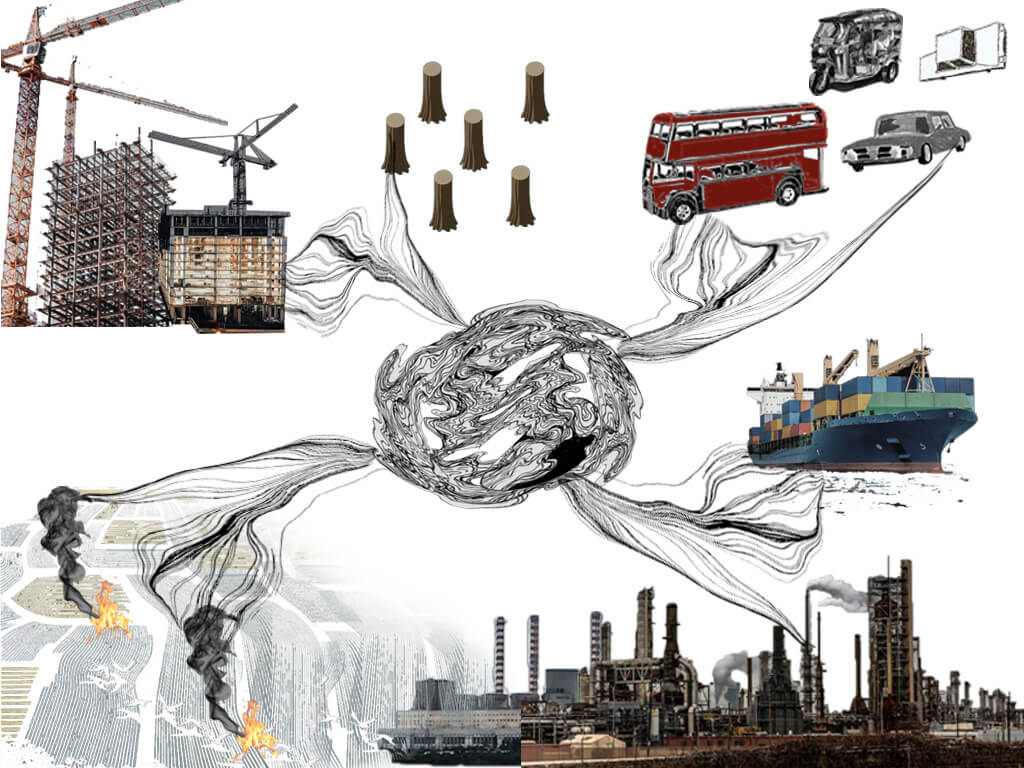

In most cities of India, the major sources of air pollution are vehicle exhaust, biomass and open waste burning, industrial emissions, road dust, power plants and diesel generators to name a few. Delhi’s PM 2.5 Air Quality Index ranges from 184 to a severe high of 449, forcing authorities to even shut down schools.

India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), aiming “to meet the prescribed annual average ambient air quality standards at all locations in the country in a stipulated time frame”.

In 2019, there were 131 cities in India whose air quality did not meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standards; with concerted effort and attention to the issue, 95 of these cities witnessed an overall improvement in PM10 levels by 2021. But the picture is still clouded by smog, not only in Delhi but also in other cities especially if they are land-locked; coastal cities like Mumbai are slightly better off as the sea breeze helps to clear the air. Despite this, Mumbai’s AQI has been in the red several times this year.

Many cities all over Asia and Africa face a similar situation with a large majority of their populations breathing polluted air and bad air leading to the death of millions every year. Аir pollution is not only an environmental risk to human health but is also one of the most avoidable causes of death and disease globally. Polluted air has turned out to be an invisible killer in cities.[1] [2]

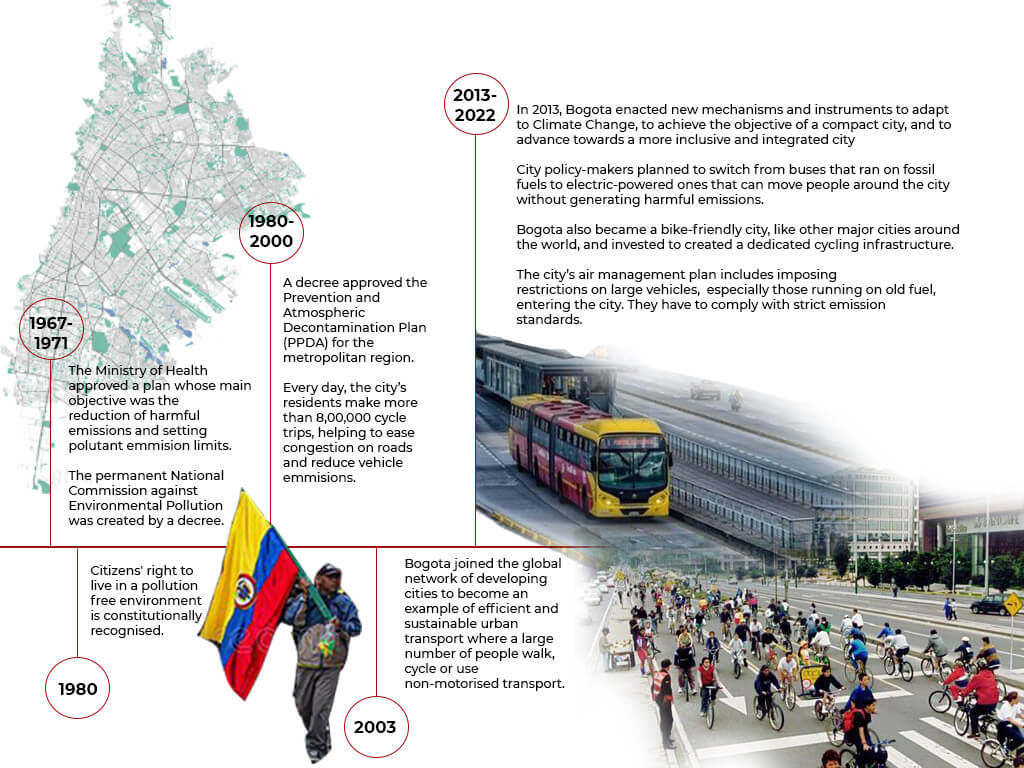

A smaller city-scale example is Bogotá in Colombia. It presents an interesting contrast with China which saw a public health crisis in the year 2013, after reports showed that 1.1 million people were dying due to the polluted air every year. It was called an “airpocalypse”. Schools, roads and airports had to be shut temporarily, and people in the polluted cities of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei and Shanghai made noise. The Chinese government clamped down on factories, took old vehicles off the road and shifted from coal to natural gas. The cities saw a substantial reduction in air pollution thereafter.[4]

Bogota chose to take the ground-up route with people’s participation. The government put a massive emphasis on the transport sector, moving to cleaner fuels for vehicles and creating infrastructure for non-motorised transport such as cycling and walking. These measures were supplemented with penalties on older vehicles. The city has 550 kilometres of cycling tracks; after the lockdown, 80 kilometres were added. The city also improved its walking routes by making them well-lit and away from traffic which saw an increasing number of people commuting on foot. The city policy-makers switched the mass transit system from fossil fuels to now run on electricity. Bogota is now an example of how a city, especially in a developing country with few resources to spare, can bring about a change in its environment, specifically to reduce air pollution and make its air healthy for all.[5] [6]

In India, the most polluted city is Delhi while the least polluted city is Imphal, Manipur. Imphal’s AQI value is the lowest in India at 11.14 μg/m3. The population of Imphal is less than Delhi, and it does not qualify as a metropolis. However, Chennai (26.06 μg/m3) is the ninth least polluted city in India, an expanding metropolis with a large population.[7]

India’s Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, was among the first laws to address air pollution. It aimed to “preserve the quality of air and control of air pollution.” A point of critique of the Air Act has been that it concentrated on large and egregious sources of pollution like factories and power shops, but did not cover dispersed sources of pollution such agrarian fields, vehicles and homes. However, the law has enabled people to take elected governments as well as large polluting corporations to courts.[8] [9]

In August 2022, the UN passed a resolution declaring that “everyone on the planet has a right to a healthy environment, including clean air, water, and a stable climate.” By formally acknowledging the impact of Climate Change on people’s well-being, the resolution allowed citizens of many countries to challenge environmentally destructive policies under human rights legislation. The Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, Inger Andersen, stated, “The resolution will trigger environmental action and provide necessary safeguards to people all over the world. It will help people stand up for their right to breathe clean air, to access safe and sufficient water, healthy food, healthy ecosystems, and non-toxic environments to live, work, study, and play.” But this is easier said than done. There are miles to go before Indians in cities can hope to breathe clean air.[10]

Maitreyee Rele graduated from School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) in 2021, where she mostly chose to work on projects on a larger urban scale. She is interested in studying people, their cultures and the society in which they unravel. An unfathomable love for films, art and every other form of storytelling make up the rest of the being.