Jane Jacobs would have been 107 years old this May 4, 2023. People rarely live to this age. It is natural for us young people to dismiss people in history as not really relevant to our times. But it would be hard to do that with Jane Jacobs who, as I read her more and more, leaves me life lessons on how to see cities, people, and spaces.

Jacobs worked primarily in New York in the 1950-60s, advocating ideas of how cities ought to be planned and built – people-centric, sensitive to the “intricate sidewalk ballet” which happens every day, and paying attention to the local or micro aspects such as paving of streets and conserving neighbourhood parks. She, of course, stood up to the power and influence of urban planner Robert Moses, who imagined New York in the classic urban development style with large buildings and highways cutting through neighbourhoods. People make cities, Jacobs asserted, and spent her life popularising the idea of making cities more local, diverse and people-friendly, receiving criticism as well as celebrity status (she was once photographed for the cover for ‘Vogue’)

More than 60 years and many generations later, if Jacobs strikes a chord in me living in Mumbai, there must be something to her work. Yet how many know her or her work, how many beyond a few students in some architecture colleges or activists engage with it? Deep-diving into her work told me that the fight for diversity and equality in cities is universal and we must not stop fighting the good fight to demand – and make – better cities.

As architect-activist PK Das*, the first Indian to receive the Jane Jacobs International Medal in 2016, said in his acceptance speech, “We often find ourselves in zones of comfort and complacence, engaging in issues and places that have achieved exclusivity, but to get out and engage with situations of instability, deal with the barriers across city landscapes and their unification is the biggest challenge for the achievement of equality and justice.” [1] Jacobs shows people like me the way.

Jacobs did not formally study urban planning but her work on the ground and keen observations more than made up for it. As Dr Amita Bhide, Professor at Centre for Urban Policy and Governance (CUPG) at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, says, “Jane Jacobs does not claim to be a universal city theorist, which is the beauty of who she is…She’s not an academic. She speaks from experience and compassion. A city is a living thing of different kinds of things coming together, a living system. She asserted that city-making is not to do with power, economy, or money, but ordinary people who give life to the streets.”

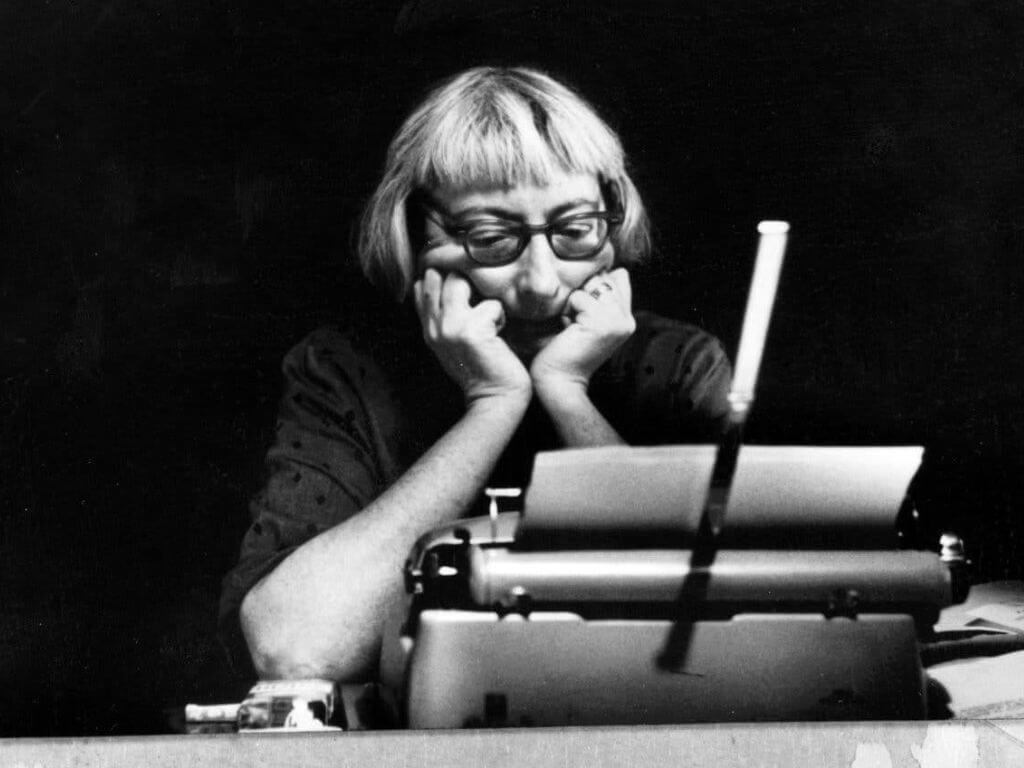

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Death and Life of American Cities

This is the title of her most-famous book published, through a grant of Rockefeller Foundation, in 1961. Written in a non-academic style, Jacobs used anecdotes and observations, introduced wordplay such as “choked downtown, haphazard suburban sprawl, blight at the heart” to describe Washington D.C., and persuaded professional planners and authorities to see urban renewal from the ground-up.

Popular terms – eyes on the street, natural proprietors of the street, sidewalk ballet – all are in this book. She writes that there must be “eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street. The buildings on a street equipped to handle strangers and to insure the safety of both residents and strangers, must be oriented to the street. They cannot turn their backs or blank sides on it and leave it blind.” Jacobs adds that a city’s sidewalks must have users “fairly continuously” on it to add to the eyes on the street. Jacobs describes her own, Hudson Street.

Mathew Idiculla, lawyer-researcher on urban issues and consultant with the Centre for Law and Policy Research, told Question of Cities why Jacobs is relevant to Indian cities: “She viewed cities as living ecosystems. They cannot, and should not, be ordered and disciplined by the brute exercise of state power…Specifically, her championing of “mixed-use” urban development as opposed to zoning cities for mono-functional land use, is particularly relevant for Indian cities which are historically mixed-use in character. Her support for denser neighbourhoods enabling more “eyes on the street” and preserving old buildings are directly relevant for Indian cities that are at the cusp of “urban renewal”.

Jacobs’s view of the city as a living ecosystem means every element – parks, neighbourhoods, sidewalks, the economy, and government functioned like a natural ecosystem. “Both types of ecosystems,” she wrote, “require much diversity to sustain themselves … and because of their complex interdependencies of components, both kinds of ecosystems are vulnerable and fragile, easily disrupted or destroyed,” she wrote. Check out the 1992 Modern Library edition of The Death and Life of Great American Cities here.[2]

Jacobs talked about the need for mixed-use neighbourhoods to encourage diversity, safety, creativity and increased opportunities for human interaction – all elements that ring true in any large Indian city in which urban development has come to stand for massive buildings and roads alone. Her ‘theories’ were often dismissed or criticised but they were, and are, borne out by people’s lived experiences. In fact, a group of academics and architects statistically tested out her “eyes on the street” theory in Philadelphia in 2017 and concluded that “crime rates were higher in neighbourhoods which had more vacant properties and lower in areas with businesses which stay open late.”[3]

Other work

Calling out planners for thinking that they could plan for an entire city in principle while these plans are applied in the form of small and specific acts done in specific places, she called planning the city “as a whole”, a delusion. “No other expertise can substitute for locality knowledge in planning,” she argued on the need for local area planning.[4]

In her book, Cities and the Wealth of Nations, published in 1984, Jacobs makes the case for local economies as essential to cities, that the development of import-replacement industries to make products from local resources instead of importing them. Unlike multinational corporations that are dictated by global economies, these businesses would be able to build strong regional roots, she argued.[5]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Jacobs versus Robert Moses

Moses was the all-powerful planner and administrator of New York holding several important positions and determining the shape and form it would take. But his view was primarily the centralised capitalist vision of the city – Jacobs opposed it tooth and nail, fighting back projects especially his proposed highway that would have cut through her neighbourhood and its parks. That protesting and writing shaped her into an urban thinker and activist.

The Jacobs-Moses faceoff was inevitable. He had an aversion for public transport fuelled his desire to build tunnels, pathways, bridges and tunnels – and he was unfazed by public opinion or what people wanted. The article, Jane Jacobs v Robert Moses, battle of New York’s urban titans, in The Guardian reads: “One neighbourhood resident, Jane Jacobs, received a flyer from the Committee to Save Washington Square Park in 1955, providing notice of the proposal to extend Manhattan’s 5th Avenue through the park…News of the proposed roadway provoked alarm. In a letter to the city’s mayor, Jacobs wrote, ‘It is very discouraging to do our best to make the city more habitable and then to learn that the city is thinking up schemes to make it uninhabitable.”[6]

Jacobs mobilised people in Greenwich Village to fight against the plan. The piece in Smart Cities Dive reads: “Robert Moses’ belief was that ‘cities are created by, and for traffic’ and in his love to move cars he had built tunnels, bridges, and highways to Manhattan, connecting Long Island to the city. It was his dream to build three highways through Manhattan: the Lower Manhattan Expressway the first to be constructed. A small group of Greenwich Village residents were going to fight the Goliath of engineering and planning, they chose their neighbour, Jane Jacobs to be David…The result was a strong and active coalition that appeared at every public hearing, wrote articles, protested in the streets, and counter-planned a healthy rehabilitation project for the neighbourhood.”[7]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In her words

Jane Jacobs, in a research paper, Putting Toronto’s Best Self Forward (1991), described an ideal street: “There are historical reasons why Toronto was laid out as a grid and why particular streets on this grid became main streets. But it isn’t for historical reasons that these main streets retain their importance and vitality…they remain the bones of the city and have much to do with its personality… One reason the main streets are so congenial and resilient is their easy adaptability, not only over time but also place. You can board a main street’s streetcar or bus and pass through an encyclopedia of neighbourhoods. The street takes on different nuances as it passes through different places, adapting to what is around it…The main streets are also very democratic spaces.”[8]

The mainstream planning did undergo changes, which professionals attribute to Jacobs’ persistence and protests. Critics have pointed out that her approach is non-theoretical, somewhat romantic in seeing cities in the image of Greenwich Village, and simplistic in that people were shaped by their environment. However, it is a testament to how much her work and words resonate with people, in cities around the world, that they are practised and cited even today. In the end, Jacobs’s vision held its own even though the Moses’ school of planning continues to play out in cities. Here’s an assessment.[9]

In the later years of life, Jacobs lent her name and time to found the organisation, Center for the Living City[10], dedicated to advancing social, environmental and economic justice and facilitating “cities that are vibrant, adaptive, equitable communities created by and for everyone.” The website of the Center also hosts a compendium of her work as well as films made about her and videos in which she holds forth on her ideas and views. They are available for viewing here.[11]

The Indian view

As Indian cities rapidly urbanise in form, adopting the Moses model as it were, certain characteristics stand out – gated communities, cleared and lifeless streets, slums and so on giving rise to a broken city fabric.

“In India, there is a great need to recognise that people make cities, which is why we need to bring in a lot of Jane Jacobs’ thinking into planning, governance and policy…(but) we have no respect for local institutions, local life. If we think of people’s participation it’s after making plans, not while or for making them,” explained Dr Amita Bhide. In Vadodara, Gujarat, she cites how nukkads or street corners where older people congregated gave way to wider roads under the Smart Cities Mission, taking away people’s space.

Dr Sheema Fatima, a post-doctoral researcher studying digitalisation in Mumbai’s urban periphery interprets ‘eyes on the street’ in the contemporary lens of increasingly polarised cities. She says, “Eyes on the street are supposed to be there for neighbours to look out for each other but this is now taking the form of monitoring and surveilling women, inter-caste dating, love marriages, what people are eating and drinking for moral policing.” She adds that if people really engaged with Jane Jacobs beyond principle, cities would be more empathetic, houses that are being bulldozed would not receive applause and people would not be unbothered about slum evictions.

*Disclosure: PK Das, architect-activist, is also the Founder of Question of Cities.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover photo: Jacobs Papers via The West End Museum