Jane Jacobs is not a well-recognised name in India. Familiarity with the US-Canadian journalist-urbanist-activist and her work is limited to academia and architects. But there isn’t a better time than now to revisit the formidable figure who has influenced urban thinking, especially about common people and their everyday lives in cities, as cities stare at sharp inequalities and gentrification. The future of our cities depends on, as Jacobs advocated, our ability to know our cities and neighbourhoods. What better way than to walk around, discover and come upon little epiphanies?

Jane Jacobs Walks or Jane Walks started in India only a few years ago but the idea is picking up momentum. In 2013, Jane Walks were hosted in Chennai, Puducherry and Mumbai. This year, walks in Gurugram and Imphal will be hosted to mark Jacobs’ birth anniversary. Question of Cities speaks to four women behind the Walks — Alisha Sadikot, an independent museum, art and heritage educator, in Mumbai; Urmi Buragohain founder of PlaceMaking Foundation who conducts Jane Walks in Imphal; Nidhi Batra, founder of Sehreeti Developmental Practices who launches the walk in Gurugram this week; and Vidhya Mohankumar, founder at Urban Design Collective who has hosted the walks in Chennai, Puducherry and Mumbai.

What drew you to Jane Jacobs and her ideas or ways of seeing a city?

Alisha Sadikot: As I got interested in the contemporary story of Mumbai, I started looking for people who wrote about cities because I’m not an urban planner or architect. Jane Jacobs’ language, I found, addressed regular people. I liked the way that she spoke about cities. She tried to convince people about what she saw as valuable in city spaces and streets, she talked about what I like about Mumbai’s neighbourhoods. People are being told that things that give life to the streets – chaos, noise, low-rises, walking – are not good. To me, it felt as if she could have been talking about an old Mumbai neighbourhood.

Urmi Buragohain: I was exposed to her ideas when I was in college. Her anti-authoritarian stand appealed to me but it took years for her principles to sink in and make sense. After working in Australia, the Middle East, Qatar, and now in India, her core message is clear — it’s the people who make cities and not buildings.

The traditional planning approach, particularly in the Indian context, still fails to acknowledge this; people are expected to fit into a plan which is sometimes quite rigid and two dimensional.

Nidhi Batra: I think early on in my urban design studies, I realised the main difference between architecture and urban design. An architect is often this demi-god providing for the client, creating a big marvel, with a strong idea of ‘ego’; an urban designer thinks of people because the act of city-making is itself a collective act. This way of looking at the process of city-making attracted me to Jane Jacobs’ work.

Vidhya Mohankumar: The first book in our master’s programme in urban design in the University of Michigan was her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. I felt an instant connection to the words she used to describe cities and streets. Jacobs speaks about the benefits of sidewalks, the “eyes on the streets” which fits perfectly in the Indian context. I immediately connected to her ideas.

Photo: PlaceMaking Foundation and Studio HOOD

How did you come to host a Jane Jacobs walk?

Alisha Sadikot: A lot was happening in 2019, I was reading Jane Jacobs and I was involved in conversations about the big things that were going to change Mumbai such as the Coastal Road and Aarey protests. Doing a Jane Jacobs walk in areas that were the city’s first suburbs might seem conflicting to what she was talking about. But early suburbanisation in Mumbai was so different from urbanisation in the West. I wanted to move away from the traditional walks in south Mumbai. I was studying Dadar where neighbourhoods were swiftly disappearing as renewal and development projects happened. I follow the Jane’s Walk festival which happens worldwide. I wrote to them asking if we could do a walk in Mumbai and they agreed.

Urmi Buragohain: I returned to India from Australia around five years ago. I am a stranger in my own hometown Imphal and rediscovering places. Now, with the experience from overseas, I look at places and issues differently and I’ve been thinking how to bring those experiences into a practical reality here. Recently, I met Shantanu from Studio HOOD and our thoughts merged. We thought Jane’s Walk is the perfect opportunity to provide a platform where people from different backgrounds can mingle.

Nidhi Batra: We have been doing walks in Gurugram but this is the first time we are calling it a Jane Jacobs walk. Jane Jacobs is not popular in India but her ideas are relevant. The idea of Jane’s Walk is to celebrate her. And it’s a good time to link with the global movement.

How did you identify the route for your walk?

Alisha Sadikot: Various things happened in Mumbai about 100 years ago that led to the growth and development of Dadar as a neighbourhood. It has changed so rapidly that today it ticks all the boxes that Jacobs was talking about. Dadar was planned to encourage people from Fort and south Bombay to move but it wasn’t just top-down planning. Communities which moved to these areas adapted the plans to suit themselves. For example, there were different types of streets which meant a lot of walking, it was mixed use so that people didn’t have to go far to visit temples, markets, parks and schools. Wadala nearby has changed too, the ground+two buildings are now high-rises. As I was walking and researching, I thought it made sense to put all these together on a walk.

Urmi Buragohain: We didn’t want to do the usual walk through the historical landmarks in Imphal. One key aspect here is its connection to water and numerous small ponds, but people are getting disconnected from these natural assets. After embankments were built along Nambul river, it further alienated the people from using the river and interacting with it. We thought we would take participants through all this and end the walk in a community hall which is a facility in all neighbourhoods in Imphal. We will experience how neighbourhoods differ and how people interact in public spaces.

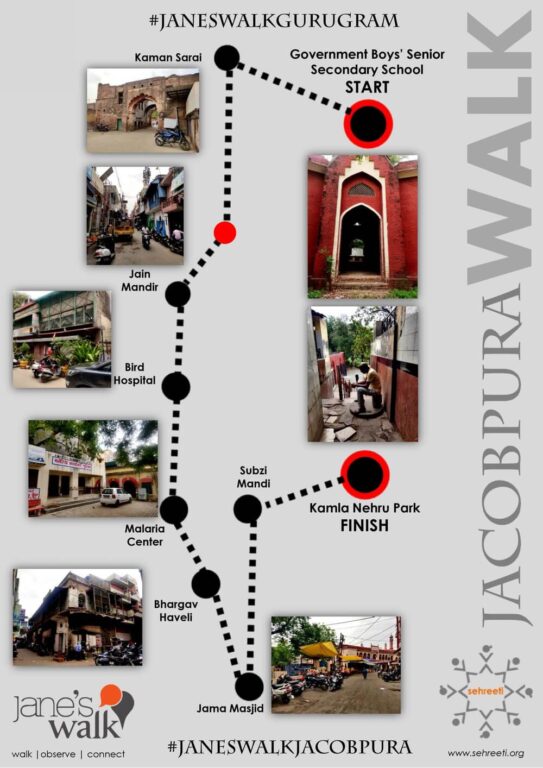

Nidhi Batra: The Gurugram walk is aimed at uncovering the layers of history, development and everydayness as a group. Gurugram is usually identified with swanky buildings and corporate life, but that is not its origin. Did you know the British were here? A Mr Jacobs, then deputy commissioner, established Jacobpura in 1861. This old Gurguram was a sarai, a market primarily of baniyas, which came to be known as sadar bazaar. This area is now super active, an important bus station connects this bustling old area to the rest of the city and Delhi. Its heritage is hidden, retail activity has taken over, old houses are now godowns, an old British-era school is demolished for a hospital. Gurugram is a palimpsest, being written over, sometimes fully erased and sometimes the text is intact. The new city has been unsympathetic to this area, it is important to engage with it now.

Photo: Nidhi Batra

How do you apply Jacobs’ philosophy to your city, which ideas of hers resonate most with you?

Alisha Sadikot: Jacobs spoke about places that are used throughout the day which is something I experienced myself. I’d be sitting in one of the small parks. Suddenly, I was surrounded by parents, especially mothers, waiting for the school nearby to let children out. Later in the day, college students came to hang out; early morning was when local residents did their exercises or just hung out. It was not lying vacant. Jacobs’ idea of “eyes on the street” and having a connection to the street outside were what we saw in old buildings with front courtyards. I came across a lot of oral histories as people talked about how they used compounds and low walls, how children used the streets. I also found that there were many different routes that you could take on your way to the station, the market, the school, and not be on just one main road for cars. I like the mixed use or multi-use, and the diversity given the different communities that live there. These areas are quickly disappearing. I wanted people to walk in these areas before they did.

Urmi Buragohain: In the Indian context, Jacobs’ concept of “eyes on the street” is something we used to have in our cities but we are becoming more and more inward looking. Manipur has gone through a long period of insurgency. Only recently is it coming back to some normalcy but people have suffered which reflects in the built environment. Buildings are dilapidated and the infrastructure is crumbling. There’s a small grocery shop in front of our gate. There are benches outside where a group of elderly people are always sitting, and seeing who’s coming and going. They are our ‘security system,’ things like this should be promoted.

Nidhi Batra: Jane Jacobs describes the early indicators of decline of cities – cultural xenophobia, self-imposed isolation, shift from faith in logos and reason to mythos. One needs to just look around India, Gurugram or other cities, to know we are facing this. Gurugram, a complete laissez-faire development and so-called millennium city, has failed to provide basic amenities for all. Jacobs went into tangible aspects of the length of a sidewalk or block so that a person can reflect on an idea while walking. In Gurugram, even planned colonies have tiny parks which I call ‘pocket handkerchief’ parks. The voice of the community is important to change the narrative of development, for this knowing the area is important.

How has the response been?

Alisha Sadikot: I have never filled up walks so fast as when I did the Jane Jacobs Walks. I think a lot of people don’t actively think about things in their daily life. For example, a lot of young people looking for homes are being told that their perfect life is inside a gated community with swimming pools and parks, and this is how they lose connection with the public park around the corner, the streets, the footpaths.

Vidhya Mohankumar: Jane Walks is a global event which happens during Jane Jacobs’ birth anniversary on May 4. But the feedback we got is that it’s too hot and exhausting this time of the year. Now, we host a walk on request. We host Jane Walks in Chennai also on August 22, Madras Day. They have been enriching exercises for us personally because of the research that goes into learning about the neighbourhood.

What are your thoughts about Jacobs in the Indian context?

Alisha Sadikot: People know of her in architecture and planning schools but no one really talks about her outside of them. I don’t think there’s a wider impact. I think that big cities already have a lot of what she saw as being the best part of cities but, in our aping of western ways of living, we are losing all of that.

Urmi Buragohain: In India, the general public is not aware of Jane Jacobs. In the US and Canada, it is different. She was from there and her principles have been applied for quite a while. Cities there started hosting these walks a long time ago and have now become a movement, gained global status and recognition. I hope the idea will pick up in India too.

Nidhi Batra: Jane Jacobs is a celebrated figure in the West, she is part of popular culture. She is almost like Frida Kahlo in the making. I love the fact that there is a Jane Jacobs Planning Division, a part of the New York’s Department of City Planning, which focuses on creating livable, sustainable, and equitable communities in the city. This is critical. In India, such collaborative design practices are emerging. The spirit of participation is very much a part of our culture. I think it is important that this spirit is nurtured, celebrated and imbibed, rather than only remembering her as an icon.

Vidhya Mohankumar: Jane Jacobs’ ideas are in the background but we use them to know more about the neighbourhood. This is a lens to understand neighbourhoods better. We have experimented in converting a walk into an audio one, or converting a walk into a series of poems about the neighbourhood. In Mumbai, we had readings from Jane Jacobs’ book. The neighbourhood shapes the walks, not the other way around.

Cover photo: Participants at a Jane Jacobs Walk in Dadar, Mumbai. Credit: Alisha Sadikot