The growing need for affordable and adequate housing in our cities has not been sufficiently addressed by the current market and state mechanisms. As a result, a part of the urban population – typically those who migrate in search of work – are forced to live on pavements, under flyovers, and in makeshift rooms. Factors such as forced evictions without adequate rehabilitation, distress migration, violence, and discrimination on the intersecting axes of caste, religion, gender, sexuality, marital status are among several reasons that lead to homelessness. Climate change-related events like harsh summers or cold winters make this condition worse.

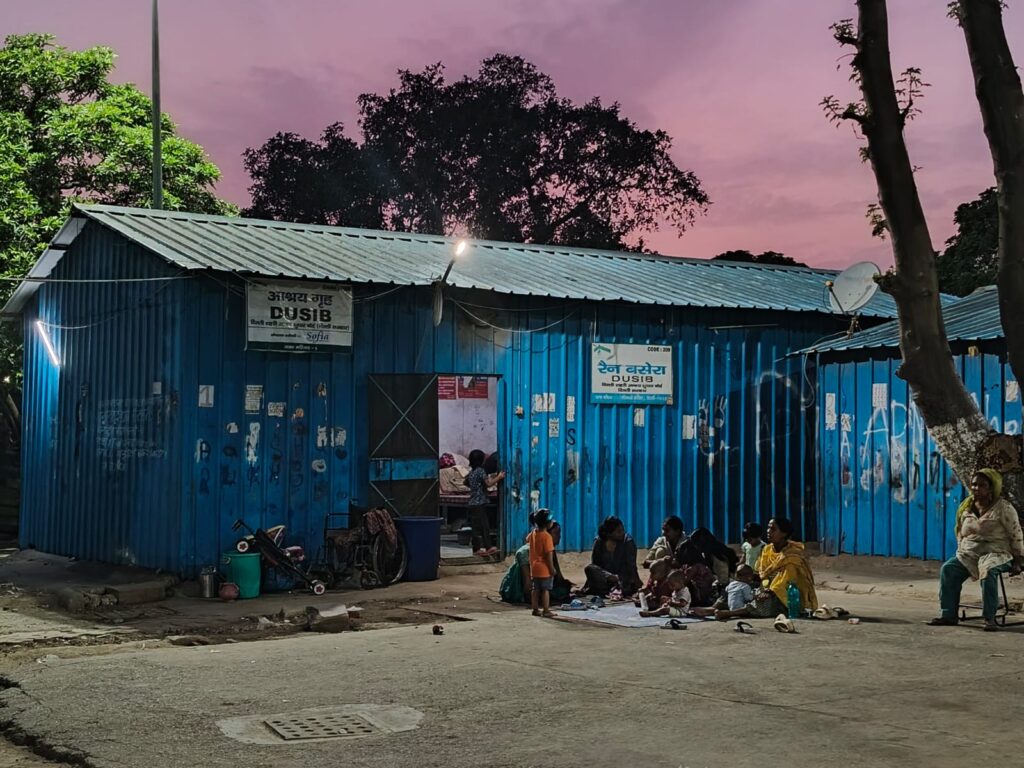

A 2024 survey by Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath (SAM:BKS), a network of organisations and individuals working on the issue of homelessness in Delhi, estimated that over three lakh people are forced to live on the city’s streets without shelter. Despite having the largest number of homeless shelters in the country – over 190, operated by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), these are not sufficient to accommodate such a large population.

The poor and homeless contribute the least to climate change but are the most impacted by it. This impact remains largely undocumented and unattended to, especially as state policies do not recognise them as a vulnerable group. For instance, the Delhi Heat Action Plan (HAP) 2024-25 outlines the need for setting up additional shelters and incorporating cool roofs, among other measures, to mitigate the effects of heat waves. However, it does not recognise specific extreme heat-related challenges of homeless persons and does not enumerate measures for their protection.

Further, Delhi’s homeless shelters are not enough to protect them from the impact of climate change. Over half of 195 shelters, nearly 103 portacabin shelters with a capacity of 6,280 people, are tin shed-like structures, often without adequate doors and windows. Instead of protecting against extreme heat, they trap heat inside, adding to the heat stress on the homeless. Without cooling shelters and public drinking water facilities, most of them struggle to make it through the day, every day, in summer. We spoke to a few to document how extreme heat impacts them and how they are coping with it. Their second names and locations have been edited to protect their identities.

‘Fans and coolers are of no use inside the tin shelter’

Gulafsha, a young domestic worker with her family of five, lives in a portacabin shelter. She cannot find better paying work partly because she does not have the requisite documents such as an Aadhaar card. Surviving on meagre family income, despite both her parents adding to hers, they find it difficult to cope with the rising heat. Her father delivers vegetables on a bicycle, even in the afternoons, and has to climb stairs multiple times to make deliveries.

Gulafsha says she feels dizzy and faint every day. The family cannot afford to buy enough water for each member. “I drink water if I have money or if I can find a public water dispenser or matkas. Otherwise, I go without it. Gala sukhne lagta hai aur paseena bhi bohot aata hai (My throat starts drying and I sweat a lot).” Gulafsha says they need at least five to six bottles of water every day for the family but can only afford one. “If there are water pots around, at least I can refill my bottle.” She recalls that people of Delhi would keep water out for birds and animals but has not seen it lately. “I hope the government places pots and bowls of cool water in as many places as possible to help us and the animals,” she adds.

Inside the tin shelter, fans and coolers are ineffective because of the trapped heat. The limited water for residents means women and children often do not have enough to bathe though the heat and sweat demands bathing twice a day as Gulafsha’s younger brother and sister would like. As water tankers do not come regularly at the shelter, her siblings cannot bathe multiple times a day. “If it becomes more hot, they will want to bathe three-four times a day. I don’t know how we will manage,” she sighs.

‘I experience sweating, weakness; I cannot bear this heat’

Reshma moved to Delhi from Jaipur 23 years ago. She survived on the streets for years but says Delhi’s heat was not as bad then. “It was not as hot, it has gotten worse now. I regularly experience sweating, physical weakness, and feel faint. I cannot bear this heat,” she says. As a waste picker, Reshma spent most of her time in the open and found it difficult to work during the summer months. “But, at that time, there were more trees and parks where we could easily find shade. That’s not the case now.”

Over the years, Delhi’s green cover has reduced and the city lost more than 60,000 trees in only seven years till 2022[1] to make way for concrete roads and buildings. Many streets are without trees that provide natural shade and cooling for pedestrians and the homeless. Our report Climate Change and the Urban Poor- Impact of Heat Waves on Homeless Persons in Delhi[2] highlights how the areas with high concentrations of homeless persons coincide with areas with high land surface temperatures. The streets provide no relief to homeless persons, the conditions in the homeless shelters are no better.

Reshma’s woes are exacerbated inside the portacabin where she lives. “The shelter gets so hot during the day that fans and coolers give little relief. It is difficult to sleep inside, so I take shelter under a tree.” She splashes water on her face multiple times a day and keeps washing her hands and feet to cool herself. “I also wet my dupatta and wrap it around my body to keep it cool.” Such measures are common among the homeless persons in Delhi but it can lead to skin irritation and bacterial growth.

Tin structures become unbearably hot during summers

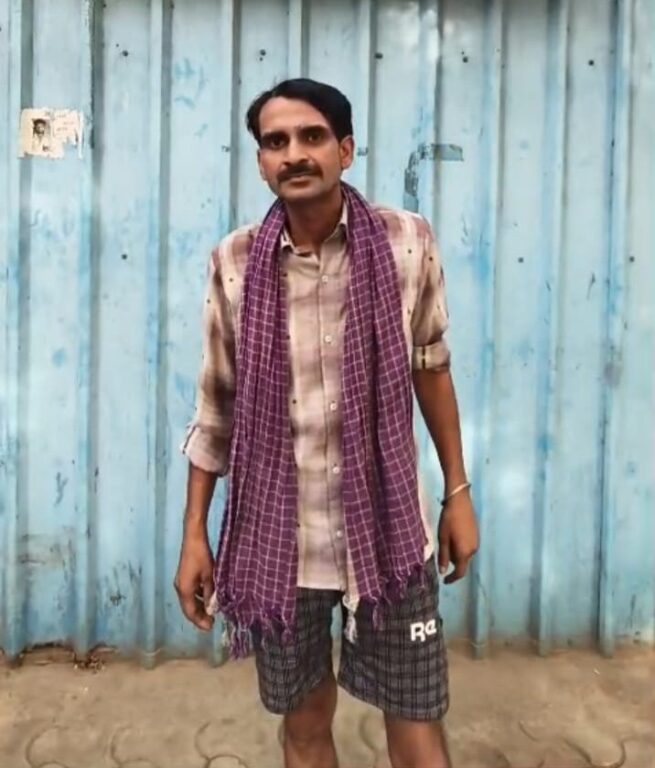

Decades ago, Sourav Kumar migrated with his family from Haryana to Nangloi, Delhi, where his father worked with the Delhi Transport Corporation. This allowed Sourav to complete his Bachelor in Arts from Delhi University. For personal reasons, he left his family in Nangloi and made his living taking on daily wage jobs and seasonal work at weddings and parties.

In Yamuna Pushta, he lived on a flyover as the nearby shelter was often full. During peak summer, the concrete flyover absorbed and trapped heat, making the nights unbearable. “There was no relief from mosquitoes and flies all night, the traffic noise made it impossible to sleep. Only the occasional gust of wind from a passing vehicle gave some comfort.” At dawn, still exhausted, he would seek shelter in nearby parks until it was time for him to work.

The rains brought no solace either as Sourav could not find immediate shelter. Sourav now takes shelter in a portacabin whenever beds are available. But the tin structures become unbearably hot during summers. “The temperature is so high, it is unbearable. Coolers are not effective.” Water scarcity makes things worse. “Earlier, I could go through the day with just one litre of water but it is not enough. We also need water for bathing…I am sweating right now. Temperatures are rising rapidly,” he rues.

‘I used to sit under trees to cool off but now they are gone’

When Iqbal came to Delhi in 1977, he was just 10 years old. A few years later, he earned a living working where he could — stores, weddings, whatever came his way. Now, around 60, his body is worn and his breath shortens with even mild exertion. “Saans phoolta hai, utna kaam nahi hota (I run out of breath, I can’t work so much),” he says. Begging is his means of survival. He sleeps wherever he finds space — on pavements, traffic islands, under flyovers in familiar locations like Turkman Gate, Himmatgarh, Delhi Gate, or stretches along the Ring Road. More than the passing cars and mosquitoes, Iqbal is bothered by police harassment and evictions. “They keep pushing us out. It’s hard to live like this. Lekin majboori hai toh neend aa hi jati hai (There is no choice but to fall asleep),” he says with a tone of resignation.

For the homeless across Delhi, this resignation is all too familiar. This summer is worse than before with the city experiencing its first heat wave of the year early in April when temperature reached 40.2 degrees Celsius.[3] “It’s hotter than I’ve ever known,” Iqbal says. With no money to buy cold water, he drinks what is available. His friend says, “The streets are too hot to sleep. So, we wet a cloth and lay down on it.”

‘Difficult to sleep at night as the ground stays hot until 5 am’

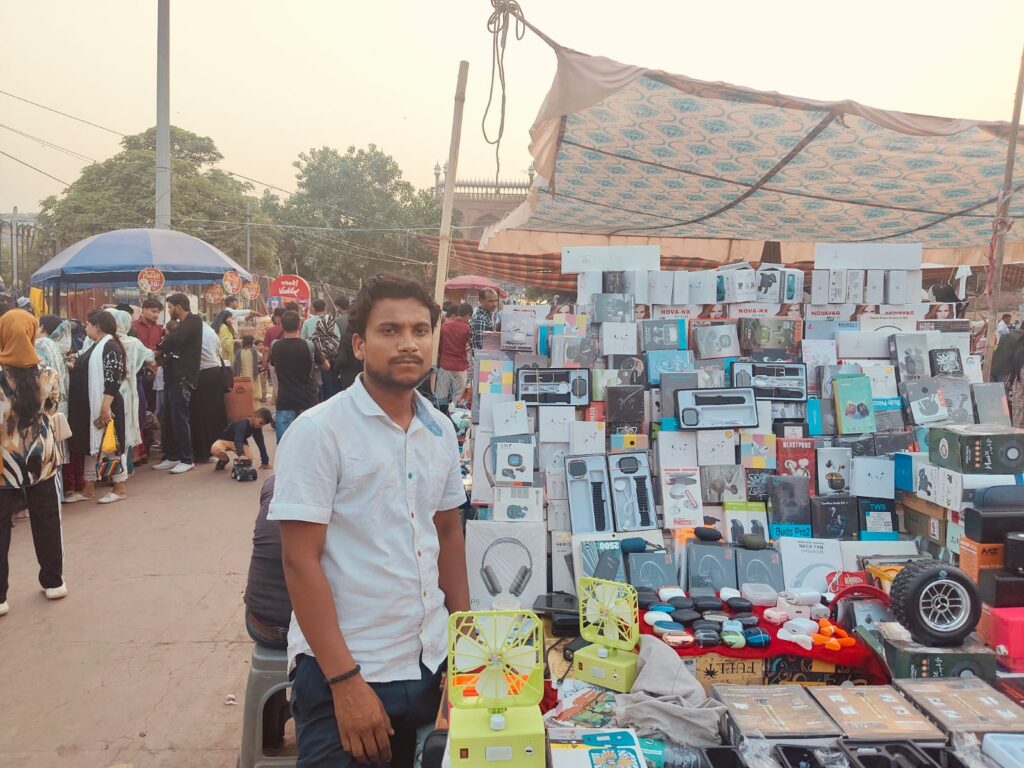

Every day, Abdul Rehman stands for hours in the hot sun, his small vending stall squeezed between hundreds of other stalls, shoppers and tourists near Jama Masjid. “When it gets too hot, I drink water or open the umbrella above my stall but not for too long. The authorities might evict us.” Originally from Bihar, Abdul came to Delhi in 2011, at the age of 14. Since then, he has been selling wares and has managed to rent a small room for Rs 5,000 a month for his family of five. His wife works as a security guard at a nearby homeless shelter, and together they just about get by.

“Twice a week, I sleep here to protect my goods,” he says. Other vendors sleep on the steps of the mosque. “The steps are hot in the harsh heat of daytime, the ground stays hot until 4 or 5 am. After that, we get some relief but it’s time to start the day.” Abdul finds the time between 12 noon and 3pm the most unbearable and tries to rest under a tree if he can get a trusted friend to look over his stall. Last May, Abdul collapsed while working. “Someone gave me glucose. I went to the nearby metro station just to be in the AC for some time before seeing a doctor.” Although he is not homeless, the precarity remains. If he loses work, he will not be able to afford the rent.

The way ahead

Across Delhi, many like Abdul get stuck in a cycle of temporary renting and periodic homelessness, struggling to maintain a sustainable income. His story underscores how housing is not just about having a roof over one’s head. It is about securing stable livelihoods, accessing basic services and infrastructure, and climate justice. Those who contribute the least to the climate crisis, suffer the most; not having a home worsens the heat impact.

With over three lakh people on Delhi’s streets unable to access shelters or basic services, increasing their vulnerability to extreme heat, there’s work to be done. The government must identify high-risk areas with high concentrations of homeless persons for immediate intervention. This must include setting up of temporary heat resistant shelters and cooling stations with water dispensers, food, electrolytes, toilets, and first-aid to counter the impact of the heat. Many public parks and green spaces, which were open to all, do not allow access to homeless persons anymore. This needs to be addressed.

The shelters, while offering some relief, are ill-equipped with facilities and services needed to cope with extreme heat. The DUSIB must ensure adequate supply of clean water, functional fans and coolers, and regular pest and vector-control measures inside all shelters. Further, as many stories highlight, portacabins trap heat. Cool roofs must be installed in existing shelters, including portacabins, as part of the programme outlined in Delhi’s Heat Action Plan of 2024.

All homeless persons must be provided access to healthcare and medical facilities, including regular visits from Mobile Medical Health Vans in shelters and high-risk areas. Welfare schemes and identity cards like ration cards, election cards and Aadhaar cards must be made available to homeless persons, irrespective of their existing documentation and proof of address/residences. Lastly, the lack of a comprehensive policy to develop permanent and secure housing options for the homeless has resulted in a piecemeal approach. The government must adopt a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritises homeless people for housing in all government schemes including access to subsidised rental and ownership housing with access to adequate finance.

With inputs by Shravani Bolage

Nivea Jain is an architect and an urban development practitioner who joined HLRN as a Program Associate in 2024. Focused on HLRN’s National Evictions and Displacement Observatory, she documents forced evictions across India and coordinates support for affected communities. She also contributes to HLRN’s wider programs and communications initiatives.

Israr Khan has been with HLRN since 2010, where he first started as Office Assistant, and then as Outreach Worker in 2022. He works closely with communities in informal settlements and homeless people in Delhi. His work involves organising community meetings, documenting personal narratives, and facilitating access to government welfare schemes to help improve their living conditions.

The Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) is a 25-year-old organisation based in New Delhi that works for the recognition and full implementation of the human rights to adequate housing and land in India. For more information, please visit: https://hlrn.org.in

Photos: Israr Khan