Bengaluru, the capital of Karnataka, was known as the land of a thousand lakes. Until 1896, the lakes and wells were common water sources till the first piped water supply came from Hesaraghatta in 1896. The water bodies are, in local parlance, tanks which were mostly built as small earthen dams across valleys to irrigate paddy fields in their command areas. But as Bengaluru grew, it incorporated them into its fold. At one time, there were close to 1,000 tanks or lakes.[1] All networked with each other and with the three major valleys which made it a unique hydrological system in any city.

These included small water bodies too. In Kannada, kere means a large tank and kunte is a small tank that cattle used to drink from. All the keres and kuntes combined would have been around a thousand, therefore the description as the land of thousand lakes. This unique water network was subjected to neglect and apathy which has led to the severe water scarcities in recent years. At present, there are about 210 lakes, and, as I understand, only 186 of them have water.[2]

Recently, I happened to be on a site visit to Devanahalli tank which we filled with treated rainwater and diluted wastewater. The managing director of the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) and three chief engineers were with me, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) zonal commissioner too came with chief engineers and officials from the horticulture department. They approved of the measures and spoke about replicating them in other tanks like we did in Devanahalli.

This showed the willingness of the authorities to be persuaded but there is a need for external pressure from civil society groups if Bengaluru’s water system has to be improved. It may be too little and too late to address the present water crisis, which is a manifestation of the prevailing political economy and land development, but it is important for the future.

Building a water supply source

To understand the present, we must go into history. In the 19th century, three years — 1874 to 1876 – saw rainfall failure which led to severe droughts as the tanks went dry and a famine ensued. Without food and water, nearly a lakh people died in the then Mysore kingdom, many of them in Bengaluru where they had migrated for jobs and food.[3] [4]

The then rulers of the city, the Diwans of Mysore, looked for a permanent water source and commissioned the Hesaraghatta Water Supply Scheme from River Arkavathi, nearly 18 kilometres away.[5] This was constructed in 1894 and water was brought to Bengaluru using steam engines. The modern city eventually got piped water from this source as well as the interconnected tanks. However, wastewater began to flow into the tanks, polluting them, causing them to stink and breed vector-borne diseases like malaria. Gradually, the tanks ceased to be sources of water for the city.

After Hesaraghatta dried up, the city started drawing water from another source, Thippagondanahalli, on the Arkavathi River in 1933. But it dried up too, forcing Bengaluru to be dependent, since 1972, on the Cauvery which is nearly 100 kilometres away and 300 metres below the city, and requires energy to pump water up to the city.[6] However, the Cauvery water is not only insufficient but also Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have been locked in a legal dispute over water sharing.

Bengaluru receives a total supply of around 1,450 million litres a day[7] but the population growth has been staggering. It went from less than a million in the 1950s to 13.6 million in 2023[8] – the growth shows as densification within the city but mostly as expansion in its periphery. The peripheral areas do not have a water supply network. The people living and working there depend on groundwater – borewells – for their water supply.

There has been a consistent increase in the demand for water[9] [10] The draft Revised Master Plan 2031 estimates that Bengaluru will require 4,282 million litres a day.[11] Borewells have supplemented the water from the Cauvery. If the groundwater depletes, the city is in trouble.

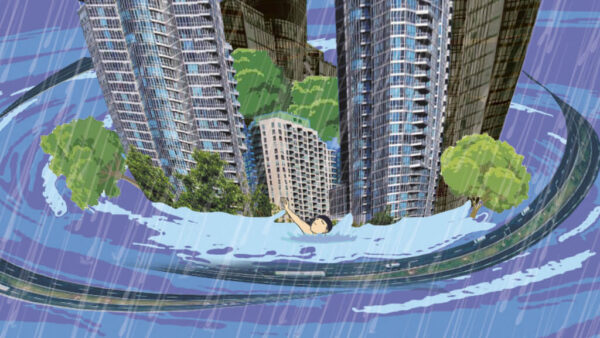

Bengaluru, like all cities, rapidly concretised which means a reduction in the green cover that helps water to percolate. The mapping by the Bangalore Urban Information System shows an alarming 1,055 percent increase in concretisation or increase of paved surfaces between 1973 and 2023.[12] This concrete forms an impermeable layer on about 800 square kilometres, diminishing the scope for water to percolate and leading to a higher runoff. Also, the intensity of rainfall has increased due to the Urban Heat Island effect. Bengaluru used to get 60 millimetres per hour; it now gets 240 millimetres per hour overwhelming the storm water drainage.[13] [14] The reduced percolation and greater runoff means floods that we saw last year when the newer peripheral areas were inundated.

The traditional way

A practical solution is to recharge the many wells across the city. We, in the Biome Trust, took this up. We were already working on rainwater harvesting, groundwater depletion, and flooding. In 2015, we enlisted the help of the Mannu Vaddar community, traditional well diggers whose skill supposedly goes back a thousand years. They were struggling for livelihood. Together, we set a target of recharging a million wells. This gave them work and Bengaluru got a partial solution to its water problem.

Since then, the Mannu Vaddars have dug nearly 2,50,000 wells and, in many areas, they ensured that the water reaches the aquifers. These areas – Yediyur, IIM Bangalore, Rail Wheel factory, Yelahanka, Cubbon Park, Lalbagh, and Rainbow Drive – do not flood as much and their groundwater has been recharging. Many are private properties, where rainwater harvesting is mandatory too, so our work does not need official permission.

The Mannu Vaddars rely on their acquired traditional knowledge which includes the location of old wells dug by their ancestors. They have visited homes with old abandoned wells and safely dug 20-30 feet deep. They have cleaned, desilted, and disinfected wells to ensure water supply round the year. Their knowledge of the location of old and new wells, and their wisdom and skills have helped to educate homeowners about recharging wells by harvesting rainwater.

Their method is to filter rainwater at the rooftop and allow it to percolate into the ground. A typical recharge well is three feet in diameter and 20 feet deep, and costs around Rs 40,000. This method has shown some results because the city has had a rainwater harvesting byelaw for 10 years which mandates new constructions to install a rainwater harvesting structure and a recharge well.

There are 750 Mannu Vaddar families at the task while a few of them work to lay foundations or excavate for pipelines and so on. They are independent workers whose work is facilitated by the Biome Trust which connects them with people. They live across the city; one location is Bhovipalya, near Sarjapura.

Lake restoration as a solution?

The restoration of lakes has garnered attention in recent times but it is important to decide the purpose of lakes in Bengaluru’s urban paradigm. They were built for irrigation which is not the purpose any more. What will the restoration of lakes give the city now? Are they for recreational purposes or to help percolation? Are they supposed to be wetlands, for flood control, places of biodiversity? Some of these functions are contradictory. So, it is not merely about restoring lakes but determining their purpose in the city’s water framework.

If they are used for flood control, they have to be drained out during rains but if also used for fishing, the fisherfolk will lose their livelihood. If they are for recreation, motorboats and other facilities will impact biodiversity. Until the purpose is decided, a lake cannot be designed or restored appropriately. The question is whether the decision is of the neighbourhood community or the city. Without this, we end up with state intervention and individual efforts which give us a ‘soup bowl’ lake, which is cleaning and mere concretisation to hold water but without the biodiversity and aesthetics.

The lakes were vibrant spaces, sometimes filled with treated wastewater and were spaces or wetlands which fostered mammalian, reptilian and bird biodiversity, spaces where people could pick fodder for their cattle, fisherfolk would fish for the cooperatives, and groundwater was recharged. Although citizens’ intervention in the revival of lakes such as Jakkur[15] or Puttenahalli[16] has softened the ‘soup bowl’ effect, the water bodies still face the challenge of untreated wastewater and construction. There is immense pressure on the lake ‘land’. It is a struggle between the real estate lobby and the lakes.[17] [18]

Treated wastewater is a great resource available through the year to supplement rainwater which drains into a lake. Besides recharging groundwater, it has microclimatic and biodiversity advantages. The appropriate restoration design would be to have a gentle slope in the lake so that birds and waders can come in and the fish can breed in the deep end. We need to make sure that certain areas are no-go zones and only certain areas are for recreation. If we craft it as a socio-ecological construct, then it can have a functional construct too.

However, lake restoration or conservation can never be sufficient; they are, at best, a supplement. Other measures will have to be taken. There are laws which make it mandatory for every new building to have rainwater harvesting, a sewage treatment plant if the gated community has more than 20 flats or 10 acres, a meter for volumetric pricing for every set of flats, dual plumbing, an automatic level controller to the overhead tank and so on. The law on rainwater harvesting is from 2009 and the sewage treatment plant from 2016; residents have to pay a fine if they fail to harvest rainwater. It is a question of persuading more people to follow them.

Tapping ahead

The shortfall is made good by water tankers. In this sense, tankers are a consequence of the state’s failure. It is only because the state does not supply water that people sink a borewell, and if it is not sufficient, they begin depending on tankers. The tankers get the water from the groundwater farther out in the city – agricultural fields, private residences and, even, burial grounds.[19]

If the groundwater is low, it takes a long time for the tankers to fill and results in soaring water prices. Tanker owners cartelise and raise prices, especially in summer, as service providers do. The government can ensure that tankers do not do price-gouging. This is where it becomes important to ensure that lakes are filled with treated wastewater allowing the aquifer to replenish. The supply increases and tanker prices could drop. This is the way to handle the tanker lobby instead of merely regulating them or determining prices or taking over the tankers. To augment the water supply by ensuring fuller aquifers is in the hands of the state.

If every household harvests 60 millimetres of rain, the water will not come into the stormwater system contributing to floods but will recharge the aquifer. At the watershed scale, lakes should be designed to receive the residual stormwater. The overflow from one lake can cascade to the next and all the way to the Arkavathi or Dakshin Pinakini river. This will enable flood control as well as groundwater recharge. In the non-monsoon season, the treated wastewater can fill the lakes and reach the aquifers below.

The challenges are that institutions in Bengaluru, as in any city, work in silos. The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB), the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) with its control of lakes, the groundwater authority, and the wastewater department within the BWSSB, have to work in tandem. Coordination is key to addressing the city’s water issues. Unless the right institutional architecture is created, water will remain a pipe dream in Bengaluru.

S Vishwanath, a well-regarded urban planner, was on a committee to frame bylaws for rainwater harvesting in Bengaluru. He is also the founder of Rainwater Club, director of Biome Environmental Solutions, and a trustee of Biome Environmental Trust. He launched the ‘Million Wells’ campaign with the Mannu Vaddar community to rejuvenate Bengaluru’s groundwater table. He is a member of the Technical Committee of the BWSSB .

Photo: S Vishwanath