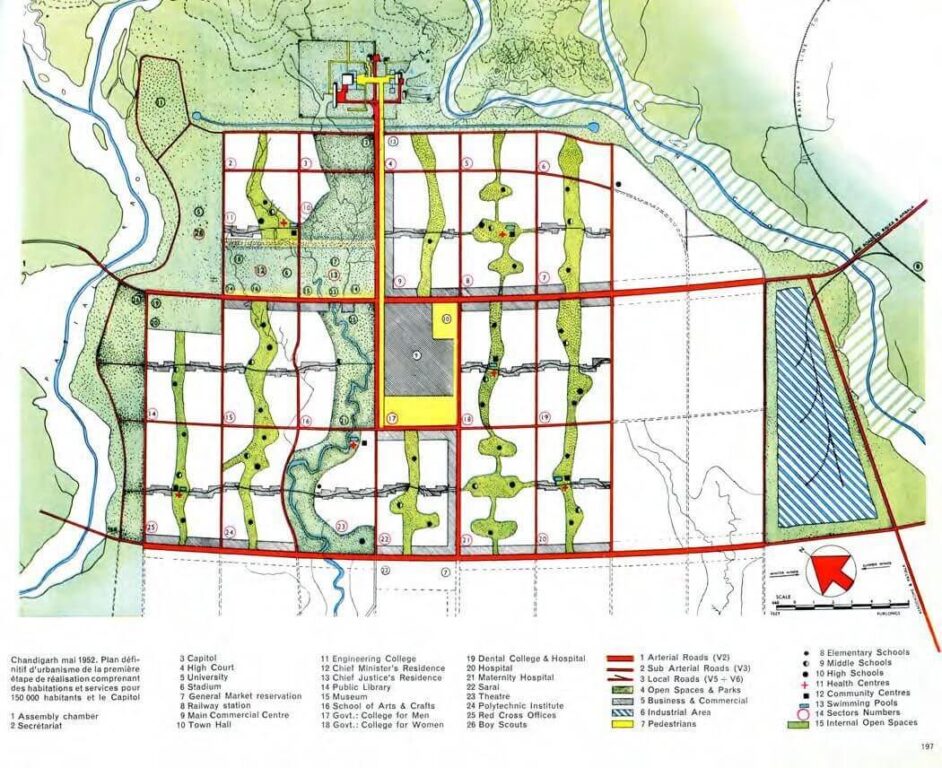

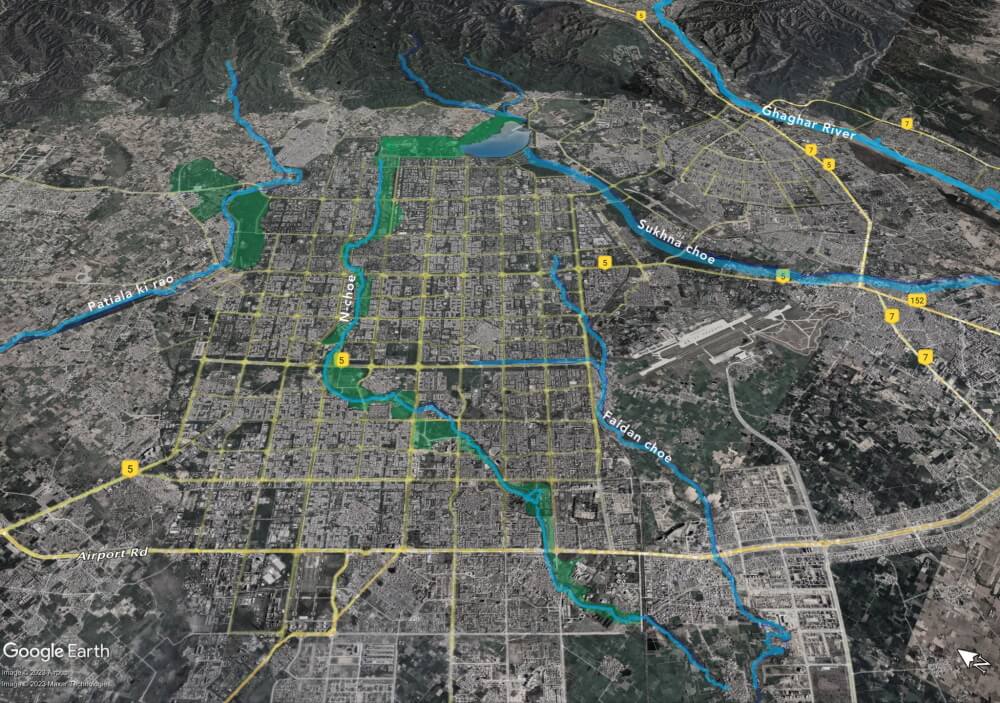

In 1948, a committee headed by engineer P.L Verma chose the site for a new town to be built as the capital for the partitioned Punjab. After considering several existing cities and taking multiple factors such as distance from the border, cost of land, availability of water and soil conditions, the committee decided to locate Chandigarh (30.74°N, 76.79°E) at the foothills of the Shivalik on a gently sloping site flanked by two seasonal streams namely Sukhna Choe and Patiala Ki Rao. A third seasonal stream, the N-Choe flows through the centre of the city surrounded by a green corridor, the Leisure Valley. The natural drainage of the city is from the North East to South West with these choes, or streams, forming its major channels.

The master plan for Chandigarh largely draws from the theories of 1940-50s, the most notable being the garden city movement. With ample green space developed as parks in each of its residential sectors, Leisure Valley running through the city, a lake and surrounding forest in the north, and greenbelt around the city, the master plan brought together a diversity of green spaces within its orthogonal grid. Aptly termed the City Beautiful, Chandigarh does offer clean(er) air, high tree cover and a well-drained city terrain to its residents.

Photo: Foundation Le Corbusier

However, a closer look reveals that the lakes, groves and gardens are mostly topological features, not living ecological places. Even though there is a romantic understanding of green open spaces, the hydrological cycles and complex ecology of a riparian forest are distant from the planners’ imagination.

Chandigarh landscape: A ‘hierarchy of open spaces’

In the hierarchy are its greenbelt, the lake, the Leisure Valley, parks, and its famous tree-lined avenues.

The greenbelt: In 1952, a five-kilometre radius surrounding the city was protected by the Punjab New Capital (Periphery) Control Act; this was enlarged to 10 kilometres in 1962. The Act mandated that no construction be permitted here, except with prior permission of the District Collector, in order to retain its agricultural and forest features. After the re-organisation of Punjab and the constitution of Chandigarh in 1966, this periphery came to be controlled by the governments of Punjab, Haryana, and Chandigarh. The romantic idea of the greenbelt has been dismantled mostly by the government projects but also by private real estate interests as well as the need to house people not accommodated in the Chandigarh plan.

The Lake: In 1958, Sukhna Choe was dammed to create the three-square kilometres Sukhna lake at the northern end. The site was a low-lying basin whose edges were raised to form the lake. The Choe came down directly into the lake causing serious siltation. To remedy this, it was diverted and three siltation pots were created from where the lake is fed. Additionally, land was acquired in the catchment area for a sanctuary which eventually became a protected wetland under the Government of India.

A bronze plaque embedded in a concrete cube at the lake declares Le Corbusier’s intentions: “The founders of Chandigarh have offered this lake and dam to the citizens of the new city so that they may escape the humdrum of the city life and enjoy the beauty of nature in peace and silence.” The city side of the lake now has a patchy amusement park, a club, tarred walking paths, harsh lighting, a restaurant and food court, and speakers playing near-continuous music. The wetland side is a thick forest area with diverse flora and fauna which migratory birds make their seasonal abode. Another lake was made in Sector 42 in 2008.

The Leisure Valley: This eight-kilometre valley stretches along the eroded seasonal rivulet N-Choe running north-south of the city. The N-Choe becomes visible in Sector 1 in the north and enters Mohali after Sector 51 before flowing into Ghaggar River. Ten public gardens flanking the N-Choe constitute the Leisure Valley. Referred to as the “lungs of the city” the linear gardens range from 55 metres to 300 metres wide. The Leisure Valley contributes significantly to the quality of life providing residents with aesthetic, ecological, social and infrastructural functions.

Sector parks: Sectors in Chandigarh are designed as “the container of family life.” There are only two vehicular entry points into each sector; a sector is divided into four blocks. Each of these (mostly) residential blocks has a small park. Chandigarh has about 1,900 large and small parks. With 38 square kilometres per capita, the city boasts of one of the highest green cover per capita among major cities in India.

Tree lined avenues: While the first phase of the landscape planning was done by Le Corbusier and team, MS Randhawa, the first administrator of Chandigarh, detailed the planting of the Rose Garden and chose various avenue trees during 1966-68. Thought was given to the structure, texture, and flowering season so that one or another avenue is in full bloom but this was ecologically questionable because the team chose single species plantation of ornamental trees for each avenue.

Walking for a ground view

Chandigarh is a network of roads, the seven Vs as they are called, supporting its status as one of India’s cities with highest per capita income and car ownership. The automobile-centered view enables a fast-paced but fleeting impression of the green city. To experience it closely, one must walk. A group of us architects, artists, students, and professionals came together a year ago to do this. There is something to be said about walking in Chandigarh; the act of walking makes one aware of the diversity of life that thrives – or not – in the interstices of its planned grid beyond its ornamental trees.

The format was simple and inclusive; anyone could propose and lead a walk after a discussion with the group. A small group usually does a recce, chooses a path, and announces it as a public walk on our Instagram handle; anyone can join. We walk, observe, and discuss the human and natural processes of our city. Some of the significant walks were along the choes and heritage zones of Chandigarh.

Photo: Jitesh Malik

Our first exploratory walk was along a popular part of the Leisure valley. About five of us started from the Rose Garden in Sector 16, a popular sightseeing spot with its pretty manicured garden hosting nearly 1,600 species of roses neatly inside flower beds. The tall central fountain is a city landmark. There are topographical undulations along the Choe which offers an immersive experience of the mountain landscape. A network of underground piped water with sprinkler systems helps maintain the smooth grass, according to the gardeners there. Much of the water used is city water – not grey water – supplied by the Chandigarh Municipal Corporation; there are serious debates about using this for parks.

Descending into the Choe gave us a closer view of drainage infrastructure and its bioswale function. In early March, the N-Choe passing through the Leisure Valley tends to be quite dry. Fallen dried leaves made crisp sounds as we treaded on them, birds hummed on trees and crickets competed to make a concert. We descended downstream. An edge of the Choe is lined with stone rubble, protecting it from erosion from the gushing seasonal flows; there were marks and debris from the last monsoon of weathered remnants of plants about seven to eight feet above the stream bed.

Mapping the bat colony

About 20 minutes of walking in the Choe brought us to a bend and a vehicular bridge – a bend not noticed from the road or gardens across the bridge. There are several such bridges and culverts along the N-Choe which ensure an uninterrupted flow of the stream below and the traffic above. In many ways, Chandigarh’s use of the natural choes to augment the stormwater drainage of the city holds lessons for newer cities. These bioswales came long before the push towards blue-green infrastructure in urban landscape design.

We had entered Shanti Kunj through this subterranean route. A bamboo grove with names etched on its smooth bark caught our attention. There are multiple ways in which people engage with a landscape; this seemed to be a lovers’ spot. Curious about what lay ahead, we walked through a grove of Harad trees to unfamiliar sounds – it was a whole colony of bats. This was the thick and narrow part of the Choe. As we jumped and crawled, the screeches turned louder and we wondered if we were going to be attacked. Something dripped on us too.

A few weeks later, we undertook a cycling trip around the N-Choe. It was spring and the city was blooming with many flowers. To our amazement, the bat colony had left that spot. The roosts are usually thousands of bats living together for about ten years. Was this the end of the roost period or had a disturbance caused the migration, were we responsible for it? Later, we came upon bat habitats south of the N-Choe in Sector 36 part of the Leisure Valley and at other places in Sectors 19 and 14.

Sensing the city

They were all Indian Flying Fox species. These bats, largest of its type, are typically urban creatures and use their deft flying skills to forage fruit from urban groves and help with pollination and propagation. Some studies show the connection between the roost location and riparian urban forests with tall trees along waterbodies. The location of the roost in Shanti Kunj seems like an ideal place; here, the Choe becomes narrow and inaccessible with limited human activity and minimum pollution of light. We will record these observations over time, connect the dots to deepen our understanding of the bat habitat, and the ecological impact. That this is a people’s effort makes it special.

Photo: Jitesh Malik

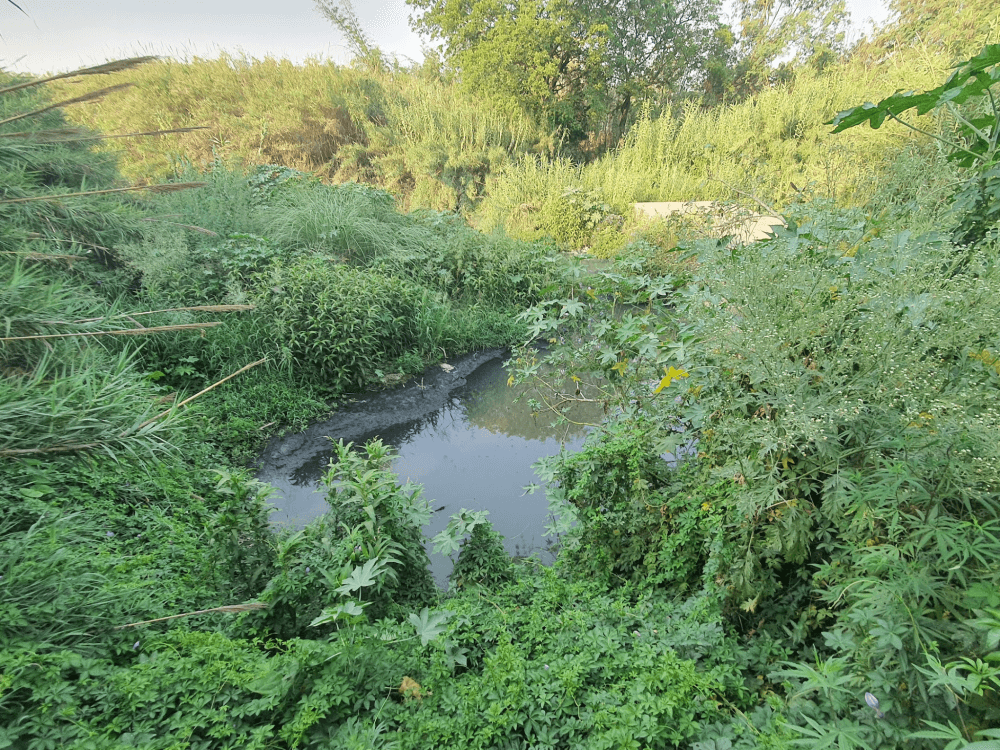

Then, we followed the stream as it left the municipal limits of Chandigarh to enter Punjab. At several points, real estate projects and government institutional areas have diverted the stream out of their campuses. Outside the boundaries of Chandigarh, the N-Choe lies abandoned, dumped with industry effluents and untreated sewage, as it flows south.

This method of sensing – not merely mapping – the city by walking allowed us an embodied experience. It was a reflexive process where sounds, touch, sights and smells evoked awe, surprise, fear, discomfort, and joy in us. The walking experience is but one of the multiple ways in which we can engage with the city’s ecology. The diverse composition of the group allowed us to discuss artistic, ecological, social, architectural, and technological readings of our city. For example, after a walk, a cyanotype printing workshop was organised and, at another time, the group documented diverse grasses along Patiala Ki Rao.

Photo adapted by Jitesh Malik

Zooming out: From the stream to the river

Chandigarh is constructed over an area of 114 square kilometres and around 50 per cent of it is green cover.[1] The streams that flow through the city originate in the Shivalik hills in the north. The N-Choe meets the Faida Pind Nallah on the immediate outskirts of Chandigarh and continues to the Ghaggar River near Patiala. The Patiala Ki Rao flows through Chandigarh and then goes through Mohali, Nayagaon, Kharar and Landran to eventually merge into the Sutlej at Bali Kalan, near Ludhiana. The Sukhna Choe joins the Ghaggar River near Mirpur village in Panchkula district.

What is evident from this reading of the choes is that there is complex ecology in them and surrounding them. Streams, birds, mosquitoes, and wind transcend state and municipal borders. Yet, cities are planned and built, all our policies and laws are framed, within these human-made demarcations. All discussion about the choes stops at the Chandigarh border.

While the Chandigarh administration acts as a steward for the choes within its territory, it officially ignores them when they cross its boundary. In fact, the choes may appear as seasonal streams in the northern sectors of Chandigarh but the same choes become nallahs down south. The nallahs have become dumping grounds for sewage, garbage, and construction waste – urban ecology uncared for.

The masterplan for Chandigarh paid attention to creating parks and green spaces which lend the city its tag of the beautiful city, but it may not have fully grasped the nuances of the hydrological cycles and the complex ecology of a riparian area turned into a city. The reserved forest near Patiala Ki Rao, for example, nestles between two bustling high-traffic roads but displays facets of urban ecology such as self-sustaining forest, low-lying grass patches, and streams struggling to support life due to high human impact.

Today’s plans for cities should do better to integrate urban ecology.

Jitesh Malik trained as an architect, artist, and a landscape architect. He is interested in non-textual ways of engaging with the city and its urban ecology. He lives and works between Chandigarh and Auroville. More information about the ecological walks can be found here.

Cover Photo: Jitesh Malik