Over the past decade, several studies investigating climate variability in Hyderabad have identified two major challenges. One is the rise in temperature and urban heat island effect across the city, and the other is changing rainfall patterns leading to near-drought conditions, large variations in precipitation, and urban flooding. These are generally attributed to the accelerated pace of change in land use and the resulting changes in land surface cover, leading to the drastic shifts in local climate. The prolonged heat waves, variability in monsoon rainfall, and hot-dry winter were associated with El Nino/La Nina events over Telangana.

This has, in some measure, drawn attention to the role of natural ecology in cities. The revised guidelines issued by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs in 2015 mandate that land use planning must incorporate ‘blue green infrastructure’, ecosystem-based approaches, and integration of resilience measures within urban planning. Subsequently, the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority invited proposals for integrating blue green infrastructure for climate resilient urban and regional development.

This essay attempts to unpack the conceptual underpinning of blue green infrastructure which has caught the imagination of urbanists as a panacea to climate change events. In the dominant perspective, blue green infrastructure is not about creating resilience or adaptive capacities of communities or ecologies critical to survival but is a continuation of the commodification of nature through ecosystem services and carbon sinks embedded in the system. In fact, it is made possible by the systematic dismantling of environmental protections, disregarding indigenous knowledge, and displacement of communities.

Photo: Kulsum Nafisa

To subsume nature into an economic entity, protection and conservation laws are replaced by the rhetoric of ‘carrying capacities’ for industrial planning, ‘environmental assessment’ of megaprojects, and ‘flexibility’ of pollution control boards. The blue green infrastructure is, without doubt, a neoliberal policy of development of stable markets in ecosystem services and the economic valuation of nature. What we need is to adopt the degrowth principle of living within the earth’s regenerative limits in socially equitable and collectively supportive ways that address global and environmental crises.

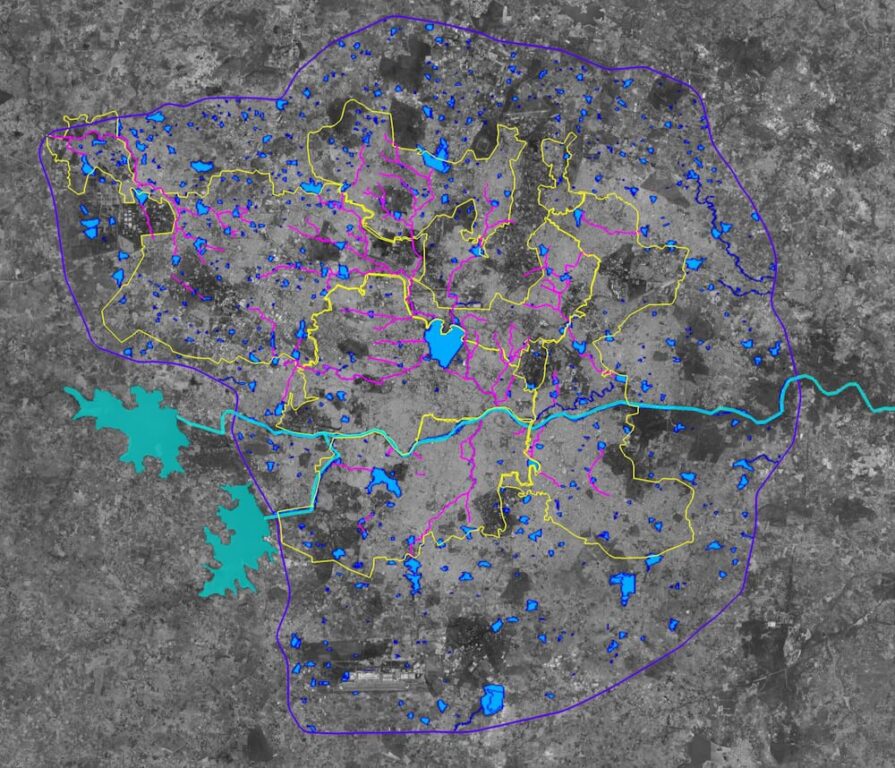

According to this WRI study[1], the rapid urbanisation of Hyderabad has resulted in an increase of built-up areas over 15 years (2000-2015) from 413 square kilometres to 581 square kilometres. This corresponds with a depletion in ‘blue cover’ from 48 to 36 square kilometres and ‘green cover’ of 65 square kilometres in a radius of 20-kilometre core region. During the same period, in the peripheral regions of the city in the 20-50 kilometre radius, the built-up area increased from 114 to 261 square kilometres while ‘blue cover’ decreased from 121 to 71 square kilometres and of 1,125 square kilometres of ‘green cover’ was lost.

The economic and functional aspects

Urbanisation is the main driver of the expansion of built-up areas including buildings, roads, and other infrastructure like special economic zones with manufacturing and service industries tied to global economic circuits. Such an expansion changes the natural environment, leading to a loss of biodiversity and disappearance of natural systems which act as a buffer against climate-related weather events. The existing natural network of the city is sought to be preserved to sustain economic growth; the natural environment is viewed through the lens of safeguarding the built infrastructure. From this perspective, the natural environment or blue green infrastructure is seen purely in a functional role.

Photo: Arshiya Syed

The blue green infrastructure is defined[2] “as a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services. Ecosystem services are a group of provisioning, regulating habitat-supporting, cultural services that natural ecosystem provide that are of value to the natural world and to humans…This network of green (land) and blue (water) spaces can improve environmental conditions and therefore citizens’ health and quality of life. It also supports a green economy, creates job opportunities, and enhances biodiversity.”

This is being promoted because it uses natural capital such as ecosystems and forests with low-impact technology and is relatively low cost. While urban built infrastructure is now defined as the primary marker of growth and development, it is important to ask these questions of blue green infrastructure: to whom will natural resources be distributed and from whom will natural resources be withdrawn.

The concept became popular after the failure of climate mitigation to ‘build resilience’ to minimise the impacts of global warming. There are two routes that blue green infrastructure takes as its starting point. One is an extension of green infrastructure from landscape urbanism[3] through technological means of providing ecosystem services and ensuring their production, and two, as a separation from urban grey infrastructure through engineering to remove stormwater quickly and improve water quality.

The primary purpose of the blue green infrastructure is the management of urban stormwater, reducing runoff, and lessening the possibility of urban flooding whose frequency has increased vastly in the last two decades. There are economic benefits – it is less capital intensive, reduces water treatment costs, increases groundwater resources, increases investment, land and property value; environmental benefits – besides reducing the flood risk and runoff volumes, improving water quality and groundwater recharge, reducing UHI, and improving biodiversity. Its social benefits include improved physical health, mental well-being, quality of life, increased public safety, healthier air, spaces of recreation and leisure. [4]

Reducing economic risks associated with flooding, heat waves, and other environmental stresses justify the investments made. Civil sector institutions like think tanks, NGOs, professional advocacy groups, scientists and academics promote the ecosystem services of blue green infrastructure as commodities based on ecological analysis[5] of abstraction (blue/green/grey), measurement (function/benefit), and classification (carbon sinks/pollution capacity).

Within the urban development and design discourse, blue green infrastructure is regarded as a complex subject, functioning as a placemaking process, to include environmental and water resource management in an existing urban fabric. In its broadest sense, it is the alignment of engineering with landscape and urban planning, hydrological planning, architecture, health and wellbeing, economic development and climate change.

However, the blue green infrastructure approach involves a capture of resources by transferring public assets into private hands and expanding private role in the public sector, thereby limiting public access to decision-making processes. It treats climate as a resource and, thus, finds a way to attribute an economic value to it.

This approach exacerbates inequality by disempowering minorities and worsening wealth concentration in cities but blue green infrastructure creates, enables, and sustains the services and institutions required for economic growth. Despite market-driven development increasing vulnerability and reducing urban resilience, the proponents of blue green infrastructure position themselves as champions of resilience.

Illustration: Kulsum Nafisa

Questioning the Hyderabad model

Two decades of continuous branding and marketing of Hyderabad as a ‘model of development’ of economic growth and improved urban liveability for external investors and expatriate white-collar workers took a severe hit in October 2020 when the city was severely flooded because of a deep depression in the Bay of Bengal, caused by the global warming of seas. While parts of the old city relied on century-old stormwater management infrastructure, the newly developed areas with vast gated communities, commercial zones of conspicuous consumption, and economic infrastructure supporting the IT and services industries were all paralysed.

This was due to the inadequate underground infrastructure such as drainage systems and mismanaged land planning which did not account for water flows, topography, and zoning. Similar events have happened since, the latest on June 6 this year when Hyderabad received heavy rainfall leading to waterlogging and massive traffic disruptions. The official data showed most areas registering 57 to 85 millimetres rain in a few hours.[6]

In 2020, to retain the image of ‘Brand Hyderabad’, the government of Telangana quickly constituted a new department and launched a project to improve flood resilience called the Strategic Nala Development Plan (SNDP)[7]. Despite studies by various consultants, the department was primarily staffed with civil engineers who assessed existing nullahs, stormwater drains, and critical narrow points. The first phase covered 1,452 square kilometres and had 58 projects to renew 80 kilometres of nullah at Rs 982 crore. It involved debris removal, desilting, solid waste disposal, and the establishment of several sewage treatment plants (STPs) and box drains. The next phase was more contentious; it entailed the demolition of thousands of encroachments to widen the nullahs before transforming them into parks, walkways, and leisure and recreation zones.

A similar policy is shaping the development[8] of what the government has identified as man-made lakes, of which 185 lakes are in Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) area. While these lakes were originally meant to supply water, they are connected through swales and shallow drains, ultimately flowing into Musi River and serving as flood mitigation. Besides the mitigation, the government intends to improve liveability, capture land value through ‘clean and odour’ free lakes, and create walkways, small parks and generate new economic activities.

Following the National Forest Policy which mandates that states must have one-third of their land as forests, the state launched ‘Telangana ku Haritha Haram’[9] (Garland of Telangana). A massive plantation programme was started for every possible open space outside forests to increase the ‘green cover’ from 25.16 percent to 33 percent. In the GHMC area, 7 crore plantations were done and 1,976 nurseries established. In addition, the creation of new parks near the lakes and heritage conservation of stepwells were included as green efforts. Recently, the Act to protect and preserve water sources, landform, and trees was modified to remove 40 types of trees that previously required felling permission.

Photo: Arshiya Syed

Limitations of blue green approach

These projects provide an empirical understanding of the danger of relying on the narrow blue green infrastructure approach to mitigate climate change effects in cities, as well as the inadequacy to understand that climate resilience depends on the preservation of the natural environment in cities. The compartmentalised focus on water as an isolated element in the city comes from a functional approach of preventing and managing urban flooding.

Similarly, the restrictive understanding of ‘green’ in terms of a quantitative measurement of tree cover results in a flawed understanding of trees and vegetation as interchangeable units, whose role and effect is understood only through numbers. This blue green approach understands climate mitigation only in terms of specific problems such as flooding, pollution, heat island effects, temperature rises, and unpredictable weather patterns. These problems are addressed through functional solutions: The management of water and the planting of trees.

Additionally, it has immediate harmful effects on the social fabric of vulnerable populations who inhabit these locations where the SNDP and Haritha Haram projects require their land. For instance, the demolitions of settlements along Musi River will displace a large number of poor and render them homeless. Secondly, the riverfront development plans to[10] divide the 20 kilometres into three river zones – the leisure area from Outer Ring Road to the walled city as an entertainment zone neatly integrates with the existing gated communities nearby but these will be saved from demolition because of their relative position and land values.

Photo: Arshiya Syed

Not blue green but degrowth

In conclusion, the limitations of the blue green infrastructure approach call for a shift in policy and planning to foreground the preservation of a city’s ecological system as a whole, and emphasise a more holistic interconnected web of water, soil, topography, seasonal variations, landscape, and socio-cultural factors. Such a shift will also require a change in the understanding of the environment as an integrated system, of which cities and their population are one part, rather than as commodified collections of individual water bodies and vegetation.

This will only be possible if climate mitigation policies in cities are decoupled from their role as enablers of economic growth. What we need is degrowth that recognises the physical limits of growth, and questions the neoliberal dimensions of development. Degrowth is an invitation to be on the long journey of decolonising our growth imaginations. It insists on deconstruction and re-evaluation of beliefs within the urban context, and the relationship between capitalism and productivism, consumerism and materialism, development and the quasi-religion of economics, science and technology.[11]

As Herman Daly, American ecologist-economist wrote, “We have many problems – poverty, unemployment, environmental destruction, climate change, financial instability but only one solution for everything, namely economic growth. We believe that growth is the costless, win-win solution to all problems, or at least the necessary precondition for any solution. This is growthism. It now creates more problems than it solves.”[12]

In this perspective, blue green infrastructure is merely a neoliberal tool in the garb of ecology.

Arshiya Syed is the founder of an architecture and urban design firm Studio Maqam in Hyderabad, Deccan. She is a graduate from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, and an Urban Fellow from the Indian Institute of Human Settlements in Bangalore. She is also a visiting faculty conducting urban design and housing studio in architecture schools.

This is Arshiya’s third essay supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship to report on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia. In the first essay, which has two parts, she reflects on the making of new ‘cities’ in the neoliberal framework with commodification of land at the expense of natural environment and topography. The concluding part can be read here. In her second essay, Arshiya examines the market-led ‘sustainable’ development approach shaping Hyderabad Vision 2050 and Telangana’s State Action Plan for Climate Change which places development in the neoliberal context.

Cover photo: Paved park over Gandipet Lake in Hyderabad. Credit: Arshiya Syed