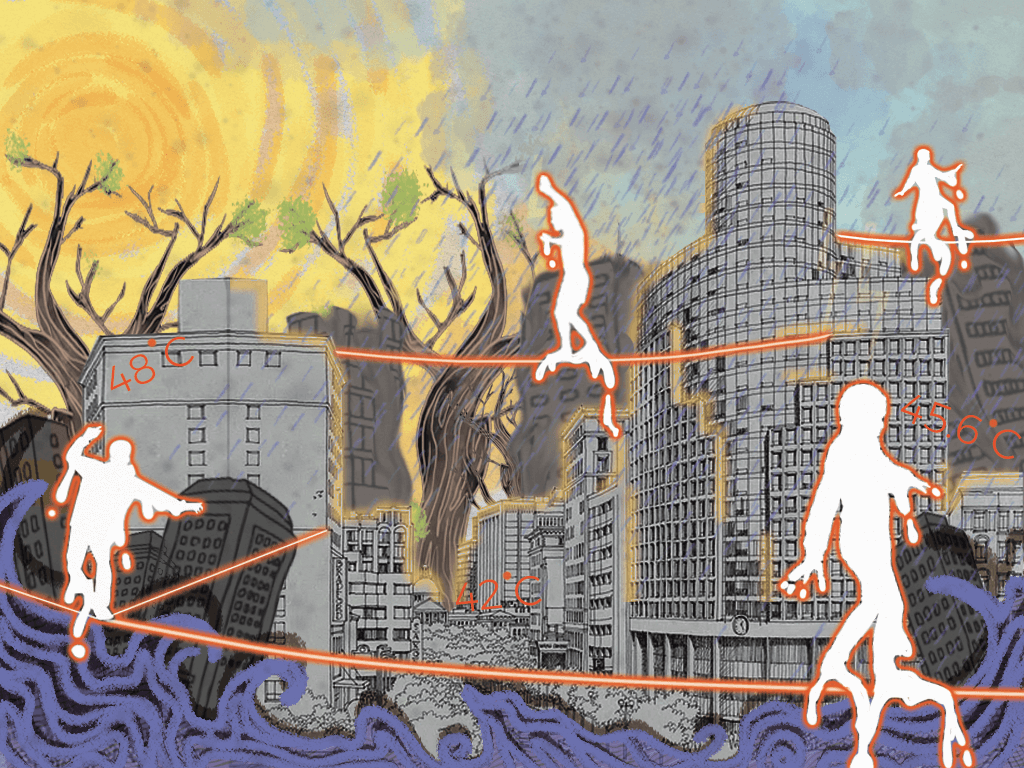

June 2024 will be remembered in contemporary history of India for the general elections that gave the country its third-term Prime Minister and its strongest opposition in a decade – and also for a climate phenomenon that rocked its land. Intense and unprecedented heat waves singed most of the northern states while unseasonal rains and floods inundated others. Hundreds died and cities across India grappled with what must be called a climate crisis. A rapid attribution analysis by Climate Central, found this not unusual given that more than 60 percent of the world’s population faced extreme heat in mid-June made at least three times more likely by climate change[1].

New Delhi, the national capital, where both the daytime and night temperatures breached previous records, registered 275 heat-related deaths in less than three weeks; many more might have gone unrecorded. While there were calls for outdoor workers to be taken off the streets during the blistering afternoons when the mercury crossed 40 degrees Celsius and nearly touched 50 degrees Celsius, there was no respite from the heat as night temperatures were the highest since 1969 at 35.2 degrees Celsius at Safdarjung station[2].The relentlessly high temperatures did not spare even hill stations in Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

Even as the northern cities reeled under heat, cities and towns in Assam, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka recorded heavy rains, landslides and massive flooding. The pre-monsoon showers in Pune on June 5 were so severe that they led to waterlogging, threw traffic out of gear, and shut down the airport. Pimpri-Chinchwad, on the outskirts of Pune, got an astounding 114.5 millimetres of rain in just an hour on June 23. Hard rain hit Delhi this week[3]. Bengaluru saw heavy rain days in May-June and severe waterlogging[4] with its wettest June day on June 2 breaking a 133-year-old record with 111.11millimetres of rain[5]. Assam reeled under floods this month[6].

As climate change-triggered extreme weather becomes more common, the questions are whether cities across India are prepared to deal with it, if they have emergency response systems in place, and if they have instituted mitigation measures and are on the path to climate adaptation. A considered review shows while a few cities have climate action plans, heat action plans, flood mitigation measures in place, these are only fitfully operational during extreme weather events while in many cities these plans are still in the making or non-existent.

The record-breaking heat in Delhi and other cities required the authorities to declare it a disaster on the lines of an earthquake or flood, but this is not even mandated in the protocols. This would have kept people indoors and safer, issued time-sensitive advisories, and alerted the healthcare system to deal with heat-related illnesses. Instead, several hospitals in Delhi even stopped sharing information on heat-related cases, as the media reported[7].

It was the same story in cities that saw massive floods – lack of information to people, chaos and congestion on streets, homes and shops inundated in no time. Bengaluru saw power tripping in many areas and commuters stranded; the flood on the Bengaluru-Mysuru road led to a 8-kilometre traffic congestion. In the past few years, floods ravaged even those cities which had not seen flooding including Srinagar and the desert town of Barmer[8].

As the intensity and frequency of heat and floods increase and cities expand mindlessly[9], the lack of preparedness to address the extreme weather events shows up. What should they do to brace themselves so that people and property are safe? How can nature-based urban planning help? And, importantly, are cities undermining climate concerns in the way they approach planning and construction?

Photo: QoC Photo

Old certitudes are failing

For decades, monsoon preparedness in most cities meant the annual exercise of cleaning and unclogging drains, desilting them, pruning trees, repairing roads and, lately, the installation of pumps to draw out water from low-lying areas. All of this is basic maintenance work. The long-term work focused on upgrading the stormwater drains network so that a higher volume of rainwater could flow out to the nearest water body. These measures are now inadequate. They fall short of what cities need to do to prepare for climate change-induced extreme events. The old framework of monsoon-preparedness itself needs an upgrade.

“Looking at the current trajectory, we are destined to get worse floods before we make any improvements,” says Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator of South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People (SANDRP), “Even when pre-monsoon work is done, it’s clearly not enough. They do it at the last moment; I have seen it in our colony in Delhi.”

For heat, a framework for heat-preparedness has to be set up in many cities. This year recorded hundreds of deaths and more than 40,000 suspected heatstroke cases[10]. Doctors signed many death certificates for heat strokes this year which was unusual, a doctor at Delhi’s Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital told the BBC[11]. The hospital opened its heat stroke clinic in May.

Preparing a city’s healthcare system to deal with heat strokes has been among the key aspects of the Heat Action Plan; recording these cases is equally important. The HAPs in Odisha prepared in 1999 and in Ahmedabad in 2013 should have nudged state and local governments to prime their healthcare system for heat waves. Yet, Delhi and other cities were caught napping. It is clear that cities can no longer afford to do only the basic mechanical preparation before monsoon or summer. This decades-old approach is proving to be inadequate – and will be as the climate impact gets stronger. This June was the hottest recorded on earth.

Cleaning the stormwater drains and dredging out the plastic that chokes it is necessary but insufficient. Heat stroke clinics, neighbourhood cooling shelters with drinking water facilities, and heat wave warnings to people are needed but they are not enough.

Nature-based planning and preparedness

What is required is a shift in understanding and gears. From urban planning to governance and preparedness, governments must recognise natural areas and factor in their role as climate mitigators. The ideal would be to embrace nature-led planning of cities[12] Climate mitigation and adaptation strategies must then follow nature-based preparedness and must be localised because different areas of a city show differing levels of flooding or heat[13].

Development and construction is planned around green spaces and watercourses, and trees are seen as a defence against climate events. More trees and green areas mean less flooding because the permeable soil soaks in considerable rainwater. Restored watercourses and dense treescapes cool down ambient temperatures and offer natural protection against heat. Changing to nature-led planning can make a climatic difference.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“Pune’s leaders could have focused on better city planning, sustainable city growth, better stormwater management, taken care of natural water areas and managed floodplains, improved drainage systems, collected rainwater, and had flood warning systems,” says Dr Shrikant Gabale, urban geomorphologist, about the rapid urbanisation there. Instead, cities rely on quick fixes.

Pune rolled out the Urban Flood Risk Management[14] programme in 2021-22 installing rain gauge[15] stations and CCTV cameras with flood sensors, and procuring pumps[16] but it did not help. The Guwahati Municipal Corporation launched Flood Early Warning System[17] with near real-time solutions but it had limited impact during this year’s floods.

‘Climate resilience’ has become a buzzword. In a limited sense, this means public services and infrastructure in cities return to functionality as quickly as possible, says Professor Raghu Murtugudde, IIT Bombay. “Ultimately, it should mean that resilience will bring the city back to being sustainable.” Comprehensive resilience would have to factor in the role of natural areas. Kochi, devastated by flash floods in October 2019, rejuvenated its canal system to make stormwater drainage more efficient[18]. though its natural areas have paid the cost of development. The East Kolkata Wetlands, a natural barrier against flood, were damaged by urbanisation but a management plan is in place to maintain the ecosystem[19]. Mumbai’s mangroves are natural flood barriers but it took years of court battles to halt their destruction.

Dr Gabale says, “Making cities flood-resilient can be achieved through a combination of infrastructure, policies, community engagement, and innovative technologies. Minute study and scientific design approach are must. Stormwater management, drainage system layouts, land use planning, flood resilient infrastructure, nature-based solutions, early warning systems, legislation and regulation, financial investments and incentives are the measures needed.” Adds Bejoy K Thomas, Associate Professor, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune, “There have been rapid changes in land use and expansion of built-up areas. Drainage systems are unable to cope and there are governance issues such as short-termism and the inability to curb illegal constructions. Another reason is the absence of basin level thinking.”

Photo: Shivani Dave

Delhi showed an alarming rise in night temperature, boiling water in taps early mornings, and an escalating water crisis[20]. Like Delhi, many cities are not cooling down at night because of increased built-up areas and concretisation. Even on days without official heat wave warnings, the threat from heat remains, this study showed[21]. Tracking the heat in Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Bengaluru and Chennai, this study[22] found that they all had become more concretised in the past two decades, contributing to the rise in heat stress.

Whichever way one approaches the heat issue, the role of depleting natural areas is a factor. Clearly then, the old-style construction-based development plans, devoid of protection to natural areas, have to be replaced with nature-based planning. This then must inform preparedness for heat and rain too.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Mandatory climate audits

By ignoring the role of planning and construction in extreme weather events, and continuing with the old approaches and frameworks, cities are undermining climate concerns. The build-more and build-higher approach on land converted from farming or claimed from forests and sea actively ignores the role of natural areas in mitigating climate events. With studies clearly showing this, if cities are unwilling to change their approach to make planning and construction more nature-led, they are undermining their own climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.

As a start, cities must undertake independent and multi-disciplinary climate audits of projects as well as their preparedness for extreme weather events. These audits must comprehensively examine the impact on natural areas due to construction, the renewal of green spaces and watercourses, the varying resilience of different areas across a city, and identify vulnerable groups most affected by extreme weather events.

“Audits have to track vulnerabilities among different socio-economic classes and risks to people, firms, corporations, industries, and infrastructure. They must assess natural hazards, vulnerabilities, exposures and effective and efficient response plans. Mainstreaming adaptation to natural hazards into fiscal policies and budgets is needed,” says Murtugudde.

Cities are, ultimately, about imagination. “You can choose a manner of urbanisation, and still urbanise,” argues Himanshu Thakkar, “For example, a concrete footpath can be designed in such a way that it also has the capacity to percolate water. You can have rainwater harvesting even on roads. And most cities have huge open spaces such as parks – Delhi is one of them – which can be hugely used for rainwater harvesting.”

If the government, as the biggest landowner, were to ensure this, it would make a difference to the city, Thakkar adds. “Groundwater is our biggest storage capacity, it doesn’t involve costs, and it is decentralised…It may not be possible to flood-proof cities but it is possible to reduce floods. This will also improve water security in cities. We can also use treated sewage as a resource to rejuvenate wetlands, streams and local water bodies.”

The buck does stop at any one office, as Dr Gabale says. “Government organisations and departments need better coordination. Floodlines should be marked for all water bodies and construction permits should be reviewed. Also, technologies like Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing technologies should be used for flood mapping, monitoring, and management. The smallest water body should be protected because it plays an important role in the behaviour of the entire water flow.” Weather stations, flood-level monitoring stations, the use of AI, deployment of staff are all government functions.

Domain experts are clear that climate audits and nature-led measures are the way forward to prepare cities for extreme weather. Are governments listening?

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.

Cover illustration: Shivani Dave