Thane, my home for the past 21 years, has historical sites, vibrant streets, amazing food and parks, besides the unmissable lakes and Yeoor Hills on the eastern edges of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. The rapid expansion of the city, adjacent to Mumbai, has meant a change in its relationship with its lakes. The famous Upvan Lake has transformed, over the years, from a quiet lake to a bustling, crowded one. Embankments have been built, edges concretised, statues and projectors installed in the water, podiums constructed cutting through the water, and a huge ghat construction is expected.[1] The project to ‘beautify’ and ‘conserve’ 15 lakes in Thane under its municipal corporation, is slated to cost Rs 53.36 crore.[2]

Despite the razzmatazz, the Upvan Lake now feels isolated, as if the beautification projects made it accessible but the waters became stagnant and dead. Would it have been better to leave it in its natural state, one that did not evict but embraced people? And what of the nearly 34 other lakes that cover an estimated 6,70,000 square feet, in varying shapes and sizes? Though rain-fed and not used as water sources, the lakes hold significant ecological and economic value. Rohit Joshi, a resident of Thane and founder of the Yeoor Environmental Society, has identified developments that harmed the lakes and regularly files complaints on issues of conservation.[3]

His latest campaign has been about the immersion of Ganapati idols made of ecologically unfriendly material in natural water bodies including the lakes here. Joshi and others want to persuade people to desist and ensure that the Thane Municipal Corporation complies with the guidelines and court orders to make immersion eco-friendly,[4] given that water bodies across Thane carry adverse impact of the immersion after Ganesh Chaturthi.

Thane’s lakes and wetlands form a complex ecological web. The city’s expansion in the past two decades has meant that these have been threatened by construction and encroachments. Like Joshi, Nishant Bangera, founder of MUSE foundation, Hema Ramani from Bombay Environmental Action Group[5], Pallavi Latkar of Grassroots Research and Advocacy, and Prof. Vidyadhar Walavalkar, president of Paryavaran Dakshata Mandal[6] have been campaigning to protect the natural wealth of the city. But for people’s efforts, the natural water bodies in Thane might have been in worse conditions.

Photo: Nishant Bangera

The TMC has spent nearly Rs 260 crore under the Smart City Mission but, instead of renewing the water network, has been dumping large amounts of debris in areas notified under the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) rules.[7] When persistent efforts to reach out to the authorities on this matter failed, Joshi filed a petition in the Bombay High Court. However, Grassroots Research and Advocacy has been working in collaboration with the TMC to renew edges and restore the landscapes in many lakes including Masunda, Devsar, Khidkali, Khardi, Desai and Kavesar.[8]

The Yeoor Hills too have seen people fight to save the greens and the biodiversity it holds with intermittent campaigns to clear the unauthorised bungalows, construction of hotels and weekend homes in the verdant forest, and protecting the rights of the Adivasis of Yeoor village by campaigning against vehicles in the eco-sensitive areas after 7pm.[9]

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

According to the National Wetland Atlas[10], Thane is a leading wetland district in Maharashtra and its lakes and creeks support a rich biodiversity besides performing ecologically-essential functions like flood control. Cities increasingly rely on natural wealth such as hills, trees, and water bodies to combat climate change impact. A threat to nature from rapid urbanisation or infrastructure projects can be seen as a violation of people’s right to life, as the Supreme Court recently affirmed.[11]

These efforts in Thane to conserve its ecology can be read in the context of the environmental resistance movements across India.[12] The striking feature of most of these movements has been that they are as much about social justice as about environmental conservation. So much of life is intertwined with ecology, after all.

Navi Mumbai story

To the south of Thane, among the oldest geographies in the region, lies the new city of Navi Mumbai planned and built in the 1960-70s. Once a verdant region with undulating hills going down to Raigad and Konkan belt, it has a network of rivers and lakes, coastal areas, wetlands, hot springs, and notified forests. Since it was first proposed covering 95 villages from Thane and Raigad districts with an estimated area of 343.70 square kilometres, the city has expanded manifold – at the expense of its natural wealth.[13]

The most controversial project has been the under-construction Navi Mumbai International Airport which has already ravaged the area’s rivers, wetlands, mangroves and hills that’s now starkly visible to anyone familiar with the area. The Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), which studied the airport’s ecological impact, showed that the airport area was a major habitat and congregation spot for many migratory and native birds but authorities have persisted.

Photo: Sunil Agarwal

Environmentalists like the late Darryl D’monte cautioned for years against locating the airport here. Activists have pursued the issue through the courts and sustained campaigns. The Conservation Action Trust, for example, filed objections even in 2020 against the environmental clearance and the relaxation in CRZ norms sought by Navi Mumbai’s nodal agency CIDCO. The airport is “an environmentally disastrous project and will cause serious flooding to surrounding villages and urban nodes,” said Shweta Bhatt, director, CAT, to the media then[14] and wondered if CIDCO or the union environment ministry had heard of climate change, sea level rise or bird strikes while clearing the project.

Another project that caused a massive uproar was the proposed golf course and residential complex over the TSC and NRI wetlands respectively. The golf course covers approximately 20 hectares; the residential complex on a 13 hectare plot is part of the TSC wetlands, according to reports.[15] https://india.mongabay.com/2020/11/navi-mumbai-couple-fights-to-save-a-bird-haven-from-becoming-a-golf-course/ Shruti and Sunil Agarwal, noticing the NRI wetlands behind their home dumped with debris, joined forces with other environmentalists and the Navi Mumbai Environmental Preservation Society to file a complaint with Wetlands Grievance Redressal Committee. The NMEPS also filed a PIL. After a long tussle, the construction was stalled and the builder asked to keep away from the wetlands. Says Sunil Agarwal, “The problem is that there is no authority to maintain these wetlands. At district level, there is the wetlands committee but they have not provided us the list of recognised wetlands. The first step is to recognise all these ecosystems as wetlands, which have been excluded from the Wetland Rules of 2017.[16]”

Photo: Rohit Joshi

Dilip Koli, member of the traditional fisherfolk community and part of the Paramparik Machhimar Bachao Kruti Samiti, has lived along the wetlands for years and has led struggles against encroaching projects. Nilesh Patil of the Aagri Koli Youth Foundation has been advocating for the rights of the indigenous people to the land and its resources. BN Kumar, founder and editor of NatConnect Foundation, among others has been a strong voice in resisting the threat to the ecology in Navi Mumbai.

“Both Thane and Navi Mumbai have beautiful lakes, water bodies and wetlands as well as lots of forest areas. These cities could have been classic cases to showcase how nature and biodiversity can co-exist with development plans but this has not happened,” remarks Stalin D, environmentalist and founder of Vanashakti, who works relentlessly on ecological conservation through litigations and advocacy campaigns.

Activism and environmental justice

Resistance can take many forms, as Thane and Navi Mumbai have shown. It does not always take the form of a protest or a large march but often reflects as small acts such as that of Rohit Joshi or Sunil Agarwal or Nishant Bangera. Individual acts can motivate others to join forces which then become movements to bring about change. Activism or resistance can be anything that questions prevalent norms and business-as-usual. In all its forms, it builds communities, energises neighbourhoods, produces knowledge and leads to an exchange of ideas or information which, in turn, nurtures the resistance.

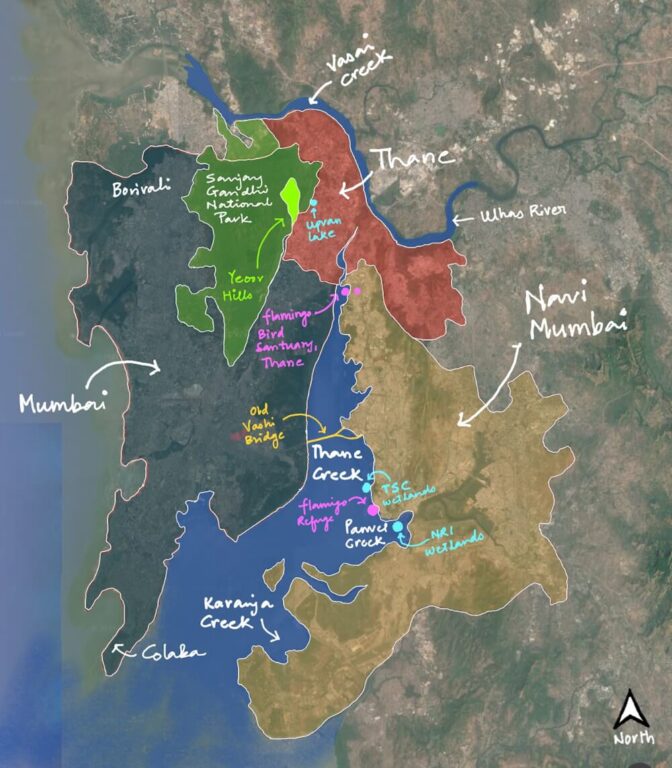

The act of mapping urban areas ecologically and making this information public could be termed as soft activism. Abhijit Ekbote does just this. An urban researcher, teacher, geospatial mapping expert and founder of City Resource[17], Ekbote is inventorising nearly hundreds of wetlands in the Thane district using remote sensing techniques and mapping those in the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) with funded research.

He says, “Navi Mumbai was planned with holding ponds. Today, after 40-50 years, the ones that exist have become wetland habitats which attract migratory birds such as Flamingos, Painted Storks, Black-headed Ibises and many types of raptors and warblers. They have become a complex ecosystem with a rich biodiversity, they are important for coastal protection, act as sponges, help in percolation, and act as a crucial carbon sink. Tidal action here helps in preventing floods in the municipal areas during heavy rain.”

He is working with a team of experts to show the ecosystem services and vulnerability parameters of these wetlands and rate them from least to most vulnerable. This will show areas highly affected by large infrastructure and development projects, so that interventions can be prioritised. A Good Practices Manual is also in the offing to assist the NMMC or organisations which intend to show the range of nature-based solutions relevant to this context.

“I feel that ‘soft activism’ plays the role of creating awareness in communities where the intent is to work in collaboration with the local government to protect the wetlands,” says Ekbote who has always believed in collaborating with all stakeholders.

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Fishing villages and their resistance

Along with Agri communities there are more than 25 Koli, or fishing, villages along the Thane creek. Their activities create an interdependent ecology and a “complex living web where marine life, mangroves and villages are linked to each other through livelihood, social, and sacred relations.”[18] Reclaiming the wetlands for development projects, which systematically reduces their claim over the water bodies, has led the Koli villages to defy orders and continue fishing.[19] Yet another everyday act of resistance.

The Kolis of Thane and Navi Mumbai have been resisting encroachment into their land for decades as their community has done in Mumbai. But with many new projects like the Third Mumbai project or NAINA[20], Golf course project[21], JNPT Project[22] and the Navi Mumbai International Airport (NMIA)[23] on the anvil, there is a constant tussle and anxiety over what will happen next. Their resistance is driven by the question of their livelihoods too as the fish catch depletes.

In 2021, the Navi Mumbai Special Economic Zone, took advantage of the COVID-19 slowdown and began the landfill wetlands and mangroves in the Uran region. There was massive resistance by the people and environmentalist groups leading the Bombay HC to halt the construction and term it illegal. CIDCO, the government’s urban planning agency, was a 26% partner in this project, which was all the more shocking to the protestors.[24] Activists like Stalin D have been vocal about “how brazen the authorities have been” in filling up rivers or wetlands.

Resistance can also take the form of advocacy as the non-profit Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) did, along with Ghar Hakk Sangharsh Samiti and Panvel Sheher Nirman Abhiyan, by hosting a people’s consultation for the Panvel draft Development Plan 2024-2044 on August 31.[25] It focused on key issues such as land use, public amenities, slum rehabilitation, and environmental justice giving insights into the discrepancies on the ground and why the Adivasi and Koli communities should intervene.

For the future of the ecology in Thane and Navi Mumbai, activists and others are hard at work today if not to stop all projects then, at least, to limit the damage to natural areas here.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, is now with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover Photo: Seawoods flamingo refuge spot in Navi Mumbai where migratory birds are spotted from October to March every year. Credit: Abhijit Ekbote