It is an April afternoon. The DPS Lake in Navi Mumbai is almost dry and heat emanates from the crevices of the lake bed. Flanked by the NRI Complex of high-end apartments and the Delhi Public School, which lends its name to the lake, on one side and large swathes of green on the other, flamingos usually land here between November and May. However, this April day, as the water level dipped, there was a lone pink baby bird who appeared to have stayed behind even as a flock of large and white flamingos left the lake.

The baby’s hope for survival lay with Shweta Mahendra, a resident of the NRI Complex, who was watching over the bird for the last two days, and trained fire-fighters who arrived in response to a distress call. They debated on how to keep the solitary baby alive as the lake dried up further. “I don’t know how this bird will survive here alone. The water is going to recede further over the next couple of days,” said a concerned Mahendra. The hardy little bird was still there days later.

The lake is one of several water bodies and natural areas in Navi Mumbai, a satellite city planned across Mumbai’s harbour in 1972 and built over the next few decades to decongest the old city. The Navi Mumbai landscape was once an ecologically-rich rural one with small hill ranges and low hills, dozens of wetlands, creeks and intertidal areas, tropical semi-evergreen and deciduous vegetation, marshlands, estuary, and mangroves.

However, in the 50 years of urbanising the area, large areas of the marsh, wetlands, salt pan lands, mangroves and other natural features have been lost – the ecological price of making a new city. Even as discussions abound on how to conserve and increase the footprint of nature in our cities, Navi Mumbai is an example of how – and how much – a city impinged into natural areas and then impacted them.

From flamingos to wetlands

Navi Mumbai has been lately marketed as a “flamingo city” to attract investors. Most of the nearly 1.33 lakh flamingos sighted last year were in the Thane Creek, adjoining the city, whereas the number of birds in Navi Mumbai’s wetlands have declined. Flamingos usually land in the water bodies here between November and May, but it is becoming harder to find them in large numbers in April because of the dried up areas.

The DPS Lake, a key site for the birds, falls dry early in the year because the flow of water from the sea has been severely disrupted by blocked water inlets. Once the water bodies dry up, they become real estate. The large housing or commercial complexes stand between the inlets-outlets of the sea and the land, blocking the water flow. If this was not enough intrusion into the natural ecology of the area, hoardings announce more high-end housing complexes in the area with fancy international names.

Against this backdrop, the announcement at the DPS Lake warning people to “not enter and disturb the free movement of flamingos, action will be taken against offenders” is an irony in itself. Across the lake, the deserted watch tower for people to see flamingos in the season stands a mute reminder of how human beings modify or tweak nature to suit themselves even as they build new cities. The lake is drying up, the flamingos are going away – or gone.

City creeping into nature

Flamingo sightings are but one marker of how the ecology here has suffered from the relentless – and unsustainable – urbanisation. This, in a planned city.

Navi Mumbai, part of the larger Mumbai Metropolitan Region, has Mumbai city to its west, Uran and Alibaug to its south, and Panvel towards its east. Now expanding over an area of 343.70 square kilometres, the city was built by acquiring and amalgamating land of 95 villages across Thane and Raigad districts. The city comprises 14 nodes which include the bustling Vashi, Airoli, CBD Belapur, Koparkhairane, Rabale, Kharghar and so on.

The City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra (CIDCO) was entrusted with the mammoth task of making the city from scratch based on a plan drawn up by the well-known architect, the late Charles Correa, Pravina Mehta and engineer-planner Shirish Patel. The Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) was formed only in 1992 to manage the basic civic affairs of Airoli, Koparkhairane, Vashi, Sanpada, Nerul and CBD Belapur but the right to develop open plots in these nodes still rests with CIDCO.

More than half of the amalgamated land has been built upon, according to the NMMC’s Environmental Status Report 2018-19. This includes residential, commercial, industrial, administrative constructions and infrastructure such as crematoriums, water supply, sewage disposal, roads, and railways.[1] As a result, the city faces Climate Change hazards such as flooding, landslides, cyclones, increasing heat waves, and poor Air Quality Index, floods and heat waves, and frequent landslides in the Parsik Hills.[2]

“There is no greenery left in the city compared to what it had, which also led to the recent heat wave incident in Kharghar,” said BN Kumar, director of NatConnect Foundation.[3]

As the city expanded, the green and blue areas shrank. The state of the wetlands is an important marker of this. Navi Mumbai has at least 13 identified wetlands with a few more in nearby Uran[4] whose extensive mudflats are important sites for migratory birds and foraging areas for shore birds. The wetlands also sustain biodiversity, allow water to percolate into the ground, and help mitigate floods.

Photo: Parag Gharat

As urban land form replaced natural areas, wetlands across Navi Mumbai have come under a great deal of anthropogenic pressure, concluded a study by the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) in 2018.[5]

In six of the wetlands studied – Panje, Belpada, Bhenkhal, Training Ship Chanakya (TSC), NRI Complex and Bhandup Pumping Station (BPS) – there was a general decrease in the area covered with salt pan, wetlands, forests and agriculture. The slight increase in mangroves, according to Rahul Khot, the deputy director of BNHS, is “due to siltation which provided an ideal environment for them to thrive”.

The Panje wetland is the largest waterbird congregation site in Navi Mumbai and one of the best birding sites in Maharashtra, noted the BNHS study. Reduction or destruction of this could lead to human-bird conflict and be hazardous given that a large international airport is being constructed here. The wetlands are under “grave threat from unsustainable developmental activities, especially landfilling for residential, recreational and commercial purposes…” the study pointed out.

Flattening nature

Like most planned cities, Navi Mumbai’s nodes have the typical sectors with wide roads and open areas. This contrasts well with Mumbai but the question remains whether, for a planned city, Navi Mumbai integrated with its ecology or ignored it.

“When CIDCO took ownership of the land in Navi Mumbai, it did not even demarcate mangroves and wetlands. After filing a Right to Information (RTI) application, we found that it considered every piece of land as developable,” said Sunil Agarwal, who has spent years getting the wetlands recognised as ecologically sensitive areas. “CIDCO has been complacent about re-classifying these as Non-Development Zones (NDZ),” he added.

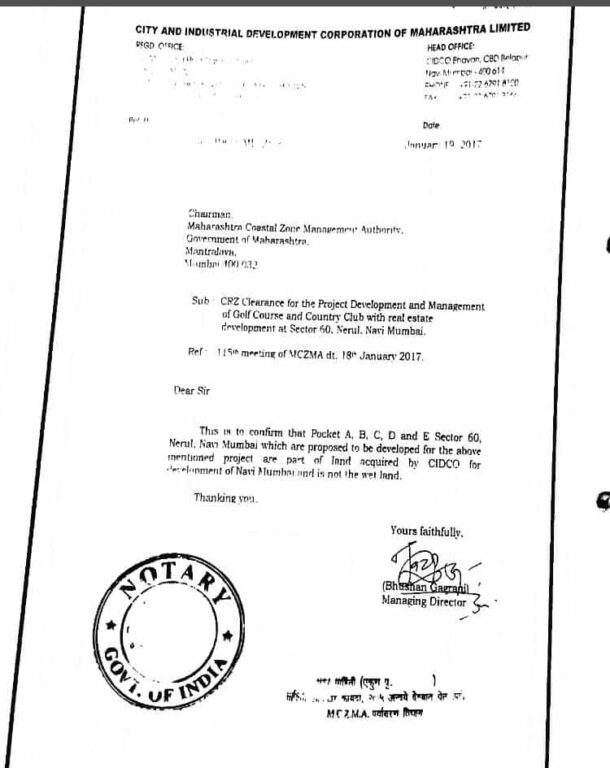

An example illustrates this. CIDCO had long drawn up plans to develop around 35.55 hectares in Sector 60 of Nerul node as a golf course and country club. A private firm was enlisted in 2004 but the land could be handed over only in 2016, by which time the plans included commercial buildings too. In January 2017, CIDCO submitted a letter to the Maharashtra Coastal Zone Management Authority (MCZMA) stating that it “is not a wetland”. This was a classic case of nature’s custodian turning aggressor.

The MCZMA allowed construction on the natural area but a counter petition was filed in 2019. “The future of the wetlands looks bleak with CIDCO generating third-party interests to generate profits from this land,” said Agarwal who, like other environmental activists in Navi Mumbai, believes has led to wetlands not being recognised as an invaluable natural resource. (CIDCO was repeatedly approached by Question of Cities for confirmation/clarification, this story will be updated as and when they reply).

The Panje wetland, for example, is adjacent to the massive Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust which makes it a strategic location for commercial development. Situated in the Dronagiri node, it is a part of the local ecology of mangroves, creeks, mudflats and marshy land that serves as a fishing area. “These are also holding ponds for stormwater and act as a flood control mechanism. Yet, 1,250 hectares were leased to a Special Economic Zone,”[6] pointed out Nandakumar Pawar, veteran environmentalist and chairperson of the Maharashtra Small Scale Traditional Fish Workers Union who used RTI applications to get information. CIDCO apparently holds 26 per cent stake with private players controlling the major share.

On his petitions in the Bombay High Court, the MCZMA declared 289 hectares of Panje, among others, as CRZ-1A area in 2018 making it a protected no-construction area. However, since all construction activity had not ceased, he went back to the HC in 2019 which transferred the matter to the National Green Tribunal. It ruled, two years later, that the inlets should be opened and all constructions and debris removed. CIDCO appealed against this – once again undermining its role as custodian of natural areas – but the NGT upheld its previous order.[7]

People as nature’s protectors

Many locals, including fisherfolk led by Pawar, are also battling vast landfilling activities. Nearly 200 hectares of the fishing zone near the JNPT was proposed to be landfilled back in 2008. When Pawar moved the NGT with a plea that the CRZ-1A area cannot be landfilled, officials claimed it was CRZ-4 which led to his petition being dismissed. His civil application is pending in the Supreme Court.

Environmentalists pointed to another worrying trend – that of the area demarcated as CRZ reducing from 100 metres to 50 metres from the high tide line in Palghar, Raigad, Ratnagiri, Thane, Sindhudurg districts over the years. Navi Mumbai falls in Raigad and Thane districts.[8] “If the areas where water fills up during high tide are being landfilled, where will the water go,” they asked.

Photo: Maitreyee Rele

Attempts were made, they said, to dry out the wetlands near the NRI Complex as well as Training Ship Chanakya (TSC) by stopping the inflow of water. “The impact can be seen in the reduced number of flamingos which need certain levels of water and fresh algae due to the intertidal water movement…If the birds don’t come here, it won’t be a protected wetland anymore. Then, the Adani group can have a report done that says that there are no birds here,” Agarwal said wryly. The Adani group is constructing the Navi Mumbai international airport here.

Development Plan 2038

In the Navi Mumbai Development Plan (DP) 2038, there is reportedly no separate category for mudflats and mangrove forests. “These ecologically important areas have been put under one land category, as creeks, making it appear like the creeks cover more area than they actually do,” pointed out Dulari Parmar, an architect and climate justice activist at Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA). In addition to the assault on natural areas, untreated industrial effluents are discharged into the sea, said Parmar.

The DP proposes a 35-kilometre Coastal Road between Belapur and Thane which threatens to wipe out entire ecosystems along the stretch. Parmar, like others, said there is no justification for the construction of this road. Another important aspect is that the initial plan for Navi Mumbai had a provision for holding ponds for stormwater management.[9]

Not only was this not followed but the DP 2038, prepared in the era of climate crisis does not even have provisions for adaptation or mitigation measures. Instead, its build-more approach could worsen climate events. Environmentalists like BN Kumar call for a Climate Action Plan covering all of Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR).

In fact, the DP 2038 does not even have a proper Existing Land Use (ELU) plan, making it difficult to map how much ecology will be lost in the next few decades.

The ‘Navi Mumbai Collective,’ a group of architects, planners and citizens demanding people’s participation in the formation and implementation of the DP, has been at this. Parmar, who is a part of the Collective, told Question of Cities, “The DP earmarks forest land for construction…The land along Parsik Hills and the forest in Belapur has been converted from reserved forests to playground/recreation ground.” The Collective has been calling for local level or neighbourhood plans, and addressing Climate Change challenges.

Activists and environmentalists have found over the years that CIDCO, NMMC and other authorities duck ecological questions or pass the buck. They can mutually discuss and do more than what citizens can, said environmentalists. Navi Mumbai is being promoted as a ‘flamingo city’ but, let alone the flamingos, even the existing green and blue areas of the city are under threat – by its own custodians – and people are fighting the good fight to save them.

There may be hope if environmental issues become election issues. As BN Kumar said, “These should be in election manifestos. There should be a demand for accountability from the authorities because governments change but the people remain.” So does nature.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover Photo: DPS Lake by Ritu Mittal