What is the current situation of wetlands in Navi Mumbai?

It is bad. In 2018-19, the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) was appointed to do a baseline study of the wetlands in Navi Mumbai as the new international airport was coming up for which environmental clearance had not been granted. The BNHS had warned that the wetlands were being buried, which was alarming. It identified five major wetlands, among them Belpada, Bhendkhal, Panje in Uran, NRI and TS Chanakya in Nerul. CIDCO which planned and built Navi Mumbai had leased out Belpada wetland to the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust, and Bhendkhal and Panje to Navi Mumbai Special Economic Zone (NMSEZ). The migratory birds visiting wetlands have site fidelity. If they do not find familiar wetlands, they may land on the mudflats nearer the airport, the BNHS had warned. Yet, all the wetlands are being systematically destroyed. For instance, at the 289-hectare Panje wetland, over five lakh birds used to flock. Now bird sightings are a rare phenomenon here.

In 2018, the Bombay High Court appointed committees[2] on wetlands and mangroves. On our complaints, the mangrove committees had asked CIDCO to stop dumping[3] debris on mangroves and wetlands but the city planner claimed helplessness as it had leased the sites to NMSEZ. Ironically, CIDCO is a 26 percent stakeholder in NMSEZ and it was shocking that it was allowed to shirk its responsibility. Then, we approached the state environment ministry which ordered a halt to the debris dumping. We — NatConnect Foundation,[4] Vanashakti Foundation,[5] Sagarshakti along with the local fishing community — have been complaining, jointly or independently, against the deliberate destruction of wetlands.

In the light of the SC order, have they been declared as wetlands and protected?

Not yet. Water is a state subject under the Constitution; it is the state government’s responsibility to conduct ground-truthing, document, and notify the wetlands identified and listed by the National Inventory of Westland Assessment (NWIA), popularly known Wetland Atlas. This is a three-step process. The documentation has to be submitted to the state’s Environment Department which directs district collectors to act further. Only the State Wetland Authority is empowered to notify the wetlands.

Our understanding is that ground-truthing has been completed and the report is to be submitted to the Environment Department. The list shows 450 wetlands across Mumbai and its suburbs plus, and over 3,500 in Thane and Raigad districts, but the protection part is far away. Take the Lotus Lake wetland in Nerul. CIDCO started[6] dumping debris here in violation of the Bombay High Court’s order. On a petition by Advocate Pradeep Patole, the HC rapped the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation when it argued that the wetland is under CIDCO’s jurisdiction.

Local environmentalists and citizens under the banner of Save Navi Mumbai Environment led by Sunil Agarwal[7] began agitating, doing rallies every Sunday, to have the debris removed. My complaint to the Centre led to the state’s Environment Department asking CIDCO and Thane collectors to explain the status of the wetland. The collectors did not respond; CIDCO sent a six-pager stating this was not a wetland and began dumping debris from the Navi Mumbai International Airport. But the fact is that the Lotus Lake figures in the wetlands list documented by the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM).

So are you saying that, despite the legal win, the lack of implementation means wetlands still do not have any legal protection?

Yes. That is the unfortunate truth. Take the case of DPS Flamingo Lake.[8] The State Wildlife Board has declared this April that the nearly 30-acre waterbody shall have the conservation reserve status following concerted collective efforts. Citizens groups such as Save Flamingos and Mangroves, Kharghar Hill and Wetlands, and Save Belapur Hills besides NatConnect Foundation held a series of silent human chain agitations. Forest Minister Ganesh Naik pushed for the protection after our presentation to him. The Forest Department and the Mangrove Cell presented the proposal to the Wildlife Board. Now we await the Government Resolution to be issued with all protection guidelines after which a monitoring committee must be set up.

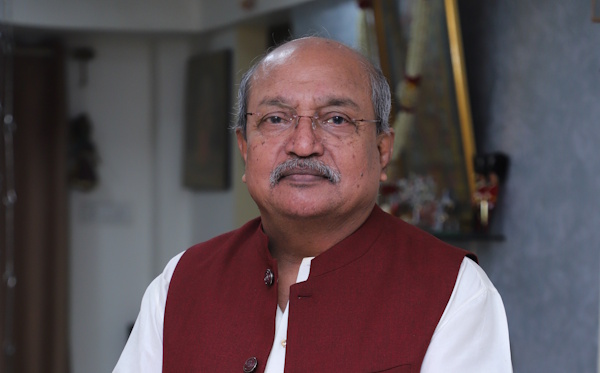

Photo: NatConnect Foundation

You mentioned approaching the Prime Minister on protection of the wetlands. Have you heard back?

Following NatConnect’s appeal to the PM, the MOEFCC officially admitted to us that only 102 wetlands of the more than 2 lakh major wetlands of 2.25 hectares are notified. This means that 99.99 percent wetlands are yet to be given legal protection. This is startling. The ministry’s Wetlands Division confirmed that while 1,89,644 wetlands have been ground-truthed (physically verified) and 1,16,425 boundaries demarcated by States and Union Territories, only 102 wetlands have so far been formally notified for protection. None of the 24,000 plus wetlands of Maharashtra are notified. The ministry says it has formulated the National Plan for Conservation of Aquatic Ecosystems Guidelines, 2024, to enable states to conserve and restore wetlands but plans and guidelines unfortunately do not translate into ground level action.

The DPS Flamingo Lake makes an interesting case study. Can you explain it given your involvement?

It is a long-drawn struggle, dating to 2010 when the Navi Mumbai Environment Preservation Society led by the late Vinod Punshi[9] launched a campaign to protect the lake from debris dumping by CIDCO and it wanted to develop land and a golf course adjoining the NRI and TS Chanakya wetlands. The Bombay HC struck it down and ordered the preservation of the three wetlands. CIDCO then moved the Supreme Court where it’s pending. Meanwhile, CIDCO designated this wetland as a developable area and the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation, in its draft Development Plan,[10] also marked it as such. Thankfully, following our protests, the status was changed to ‘waterbody’. This applies to NRI and TS Chanakya wetlands as well.

About the DPS Flamingo Lake, CIDCO had buried the inter-tidal water flow channels to the waterbody while constructing the access road to the passenger water transport terminal; another three channels were also mysteriously blocked. As a result, the lake dried up, flamingos got disoriented and many died crashing into the gigantic sign board of the terminal. Following a hue and cry, the then forest minister Sudhir Mungantiwar announced that the government would[11] protect flamingo abodes and formed a committee which recommended the Conservation Reserve status for DPS Lake. This was also endorsed by the renowned Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. When Ganesh Naik succeeded him, we apprised him of these aspects and he ensured that the proposal was on the agenda of the Wildlife Board chaired by Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis. As I said earlier, we still await the formal GR.

Photo: NatConnect Foundation

What are the continuing major threats to the wetlands?

The major threat, ironically, is CIDCO itself. It’s a commercial organisation with no care for the environment and trying to sell every inch of land. I have lived in Navi Mumbai for the past 45 years and see the change. In the 1970-80s, CIDCO used to leave 40 percent open space[12] for gardens, roads, maidans but now it’s all about monetising land. In Ulwe, near the new international airport, it put up a casting yard during the construction of the Atal Setu trans-harbour link and, after the work, began allotting the land including to a temple. CIDCO’s map shows a flood line through the temple plot which means it is a flood-prone area but it has encouraged construction.

The other threat is from the ‘debris mafia.’ Redevelopment is going on across Mumbai and Navi Mumbai; the debris goes to Kanjurmarg or Navi Mumbai mangroves and wetlands. There’s no protection to nature.[13] Even the NMMC’s flying squads which would send back the dumpers are not seen any more. Another threat is from the infrastructure projects. The permissions to cut mangroves for such projects are not monitored. For instance, a project proponent could cut 1,000 trees instead of the permitted 100 but no one checks. Official neglect and people’s apathy are big challenges too.

Now there’s the wetlands committee, mangroves committee, and Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary Management Plan. What would all the movements demand of them?

Committees and reports will come but unless the wetlands are notified, they are not protected. The notification is crucial. It’s the job of the district collectors to protect them. In the absence of any formal notification, many wetlands are being lost. This is a fight and we have already lost a huge wetland at Jasai which was landfilled by JNPT, ostensibly to build for project-affected people. Mangroves under NMSEZ land have been buried. But nature has its way. The rising sea levels and natural flow of water led to the mangroves reviving on their own.[14] The areas buried by NMSEZ at Pagote and Bhendkhal are full of water now. Nature seems to be striking back. The Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary Management Plan also faces challenges[15] as the satellite wetlands around the Ramsar site face grave dangers.

As my friend Nandakumar Pawar says, successive governments keep harping about preserving mangroves and wetlands. At international climate summits like the COP, the Prime Minister and Union Environment Minister get wetland resolutions passed. But back home, there is no serious action. We recently requested the PM to ensure notification of all wetlands with the speed he is fond of. Unfortunately, environmentalists are branded ‘Urban Naxals’ who always oppose development; all we want is to balance construction with environmental care. Wetlands act as carbon sinks, support the local economy, and recharge groundwater table. Mangroves are our frontline soldiers shielding the coastal areas from storms, tidal attacks and tsunamis.

Photo: NatConnect Foundation

The Navi Mumbai International Airport has an ecological cost. How have citizens’ movements focused on it?

First, the location is ill-suited. Airports all over the world are built far away from cities, not in the middle of them, but Navi Mumbai airport is surrounded by thickly populated areas of Ulwe, Nerul, Kharghar, Kalamboli and Panvel. Builders are selling property at high prices, citing airport views and proximity; the region is becoming congested. Then, Ulwe and Gadhi rivers were diverted, hills flattened, stones quarried from there and airport construction debris were thrown in the wetlands. The government has played with the environment and the people living here will pay the price.

A few citizen groups and environment forums fought but, ultimately, it’s not only the job of a handful of us; it’s collective responsibility. Environmental protection is a constitutionally guaranteed right under the Right to Life which places responsibility on governments and authorities. When they fail, it is nothing but an invitation to disaster. We are grateful to the National Green Tribunal and Human Rights Commission which took suo motu cognisance of media reports arising from our campaigns. But courts have their own pressures too. We are relentlessly pursuing the environmental causes by petitioning the central and state governments. Unfortunately, red-tapism blocks the green cause.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS), she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons