Navi Mumbai, across the harbour from Mumbai, is a coastal city carrying all possible Climate Change risks of an expanding and dense metropolis. This makes it imperative that the city becomes climate-informed and develops strategies to deal with the impact. Imagined in the 1960s, Navi Mumbai was developed to decongest Mumbai and develop an infrastructurally-sound satellite city. Much like Mumbai, Navi Mumbai too was developed through largescale land conversion and terrain re-engineering of large parcels of wetlands, mudflats, and salt pans. Environmental conflict was thus written into the city’s development, damaging its ecology and undermining people’s Right to Environment.

Initially steered by the City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO), the city began to be governed by the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) in 1991. It has grown to house a population of more than 1.8 million which is expected to exceed 2.8 million by 2038, according to the Navi Mumbai draft Development Plan (DP) 2018-2038. The DP offers the best opportunity to recognise the Climate Change challenges that the city faces and strategise action. However, it barely recognises the projected climate impacts.

Any review of the DP or acknowledgment of people’s Right to Environment has to identify the Climate Change hazards the city faces: Flooding, landslides, cyclones, increasing heat waves, and poor Air Quality Index (AQI).

Navi Mumbai was conceptualised with a unique drainage system where stormwater and wastewater disposal systems are separate. Despite this, several flooding hotspots dot the city – specifically Vashi’s Sector 9, Mahape MIDC, the Agricultural Produce Market Committee area, MAFCO market, Talavali village and Balaram Wadi at Ghansoli, Turbhe and Rabale MIDC. In the climate hazard mapping last year by Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA), several other locations were also seen to be vulnerable to flooding – Airoli Sector 9, Ghansoli Sectors 8A & 5, Talavali Gaothan area, Vashi Sector 19A, Sanpada Sectors 8, 18 and 19, Seawoods Sectors 30 and 25, and Belapur Sectors 4 and 5.

With the increase in population, the demand for natural resources, infrastructure, housing has intensified and the need to deal with Climate Change impact has become urgent. Climate events which occurred once every 100 years have become more frequent. For instance, cyclones which were rare, have hit the city several times recently. Cyclone Tauktae in May 2021 led to life losses in Airoli-Sanpada areas and affected the fisherfolk living in Sarsole and Diwale Koliwadas.

The eastern edge of Navi Mumbai, bordered by Parsik hills – a reserved forest area – sees frequent landslides due to a loss in its vegetative cover, deforestation, and exposed quarries. The NMMC’s City Disaster Management Report, 2015, identified eight landslide prone locations which are primarily urban poor settlements – Durgamata slum in Belapur; Mahatma Gandhi slum and Ramesh Metal quarry in Nerul; Indiranagar slum in Turbhe; Rabale-Bhimnagar, Ashwin quarry, and Ambedkar Nagar in Ghansoli; and Ilthanpada in Digha.

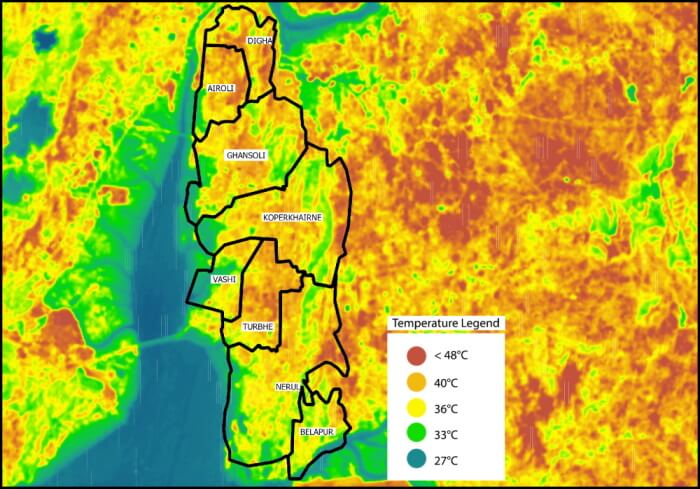

Navi Mumbai also faces heat waves and forest fires. Summers are hazardous as they are coupled with heat waves exacerbating the urban heat island effect in an increasingly concretised city. Findings from a Land Surface Temperature (LST) analysis in 2021-22, conducted by YUVA under the Climate Justice Project, shows that Vashi and Airoli areas recorded 44.8 degrees Celsius in March this year while the highest LST that month in Mumbai was 46.4 degrees Celsius in Mankhurd. Besides, parts of Navi Mumbai experienced severe temperatures too. This adversely impacts social and environmental indicators. In April this year, the city saw 10 per cent rise in schoolchildren affected by dehydration, vomiting and diarrhoea. Heat-induced forest fires have become a regular phenomenon; the exposed quarries have exacerbated this largely in Belapur-Nerul section and Mahape area of Parsik hill.

Source: YUVA, 2021-22 Climate Hazard mapping in MMR.

Navi Mumbai deals with poor Air Quality Index too; land-use planning is responsible for this. In the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) Regional Plan of the 1960s, before Navi Mumbai was planned, large parcels of land along Parsik hills were earmarked as industrial zones, a similar zone was also planned in Taloja which is adjacent to Navi Mumbai, and nearby areas were marked for housing. The highly polluting industries in the industrial zones have caused massive health impacts and environmental disruption over the years. The Maharashtra Pollution Control Board data in 2019, based on information from hospitals in the area, showed a rise in patients with air-borne diseases. On November 14, 2022, the air quality monitoring station in Mahape recorded 260 AQI – as poor as Delhi’s AQI which is deemed very unhealthy (AirVisual, 2022).

Climate-informed Development Plan necessary

It was imperative that the Development Plan 2038 (DP) addressed these and related Climate Change risks, and evolved mitigation and adaptation measures with holistic strategies. The multiple and multi-scalar impacts had to be addressed at both macro and micro scale. The DP would have then set the city on the path of climate mitigation and adaptation, and protected people’s Right to Environment.

Over the past few decades, the NMMC has committed to environmental sustainability, climate action and disaster responsiveness through three city-level action plans; however, none of these find a mention in the DP. It’s a classic case of one hand not knowing what the other has done.

Firstly, there was the Government of India’s Climate Risk Management programme (2015) to integrate risk reduction measures in development plans and undertake mitigation activities; flowing from that, the city’s disaster management plans and the Hazard Risk and Vulnerability Analysis should have been in the DP. Secondly, the NMMC’s Disaster Management Plan of 2015 highlighted Climate risks which made slums highly vulnerable to flooding, fire, and cyclones, and recommended measures for rehabilitation of people living in them. However, the DP does not identify a single slum this way, let alone suggest or develop protocols for safe rehabilitation.

Thirdly, according to the National Clean Air Program (NCAP), Navi Mumbai comes under the purview of non-attainment cities – cities that have fallen short of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for over five years. The NMMC has to implement actions for efficient mobility and connectivity, improving public transport and last mile connectivity, and so on. Though these are directly linked to urban planning and must reflect in the DP, they find no mention.

The DP is an opportunity to create a comprehensive and dynamic city plan, reflecting the present land use but also accounting for changes in the future. Given the Climate Change hazards on the horizon, Climate-informed development planning was necessary. It is disappointing that the Navi Mumbai DP fails to reference and include mitigation and adaptation strategies to reduce risk and build climate resilience.

DP ignores Climate Change

The draft DP not only has contradictions but also fails to recognise – and address – the immediate and long-term impact of Climate Change. It should have sought to conserve the existing ecologically sensitive regions to prevent greater climatic disasters in the future. For a coastal city, the coastal areas are natural buffers from the sea, and open spaces act as natural sponges to maintain ecological equilibrium neither find a mention in the DP.

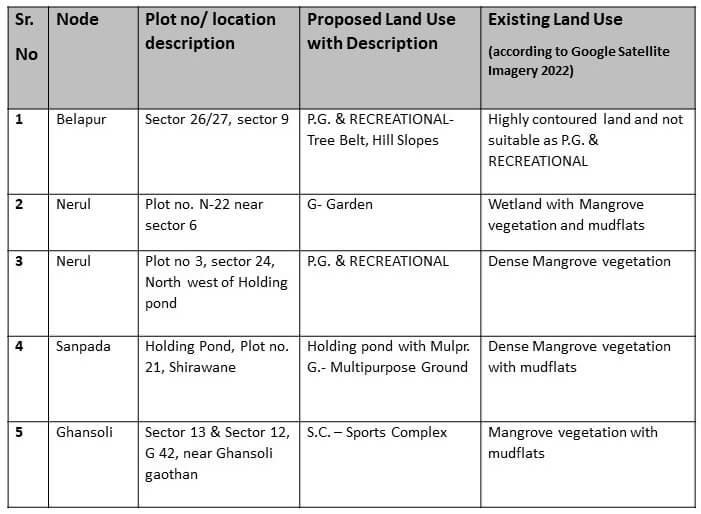

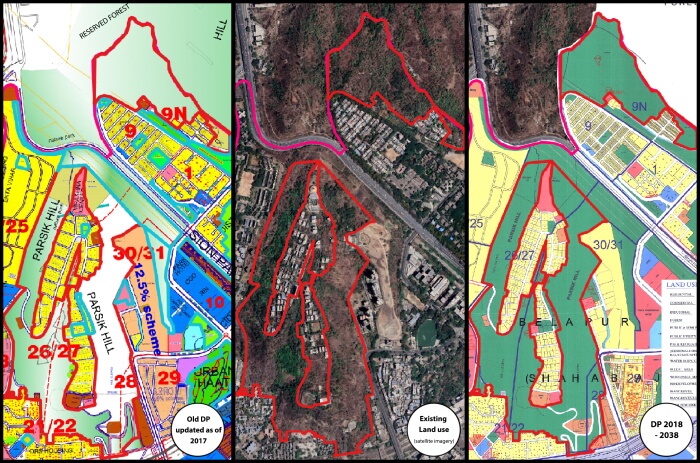

Instead of clearly demarcating and conserving existing eco-sensitive areas, the Proposed Land Use (PLU) in the DP shows several lapses. For instance, an estimated 4.22 square kilometres of forest cover has been reduced (from 26.55 square kilometres to 22.33 square kilometres), multiple land parcels allocated for playgrounds and recreational grounds have been demarcated on forests, hill slopes and wetlands with mangroves which will only lead to tree felling or conversion of these lands permanently damaging the ecosystem.

Source: YUVA

The DP fails to employ the basic Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) guidelines in marking various CRZ areas. These ecologically sensitive areas could have been delineated by incorporating one or all the documents available such as the Wetland Atlas of Maharashtra, the Forest Survey of India maps, and Coastal Zone Management Plan maps which safeguard the wetlands. Ideally, the DP should clearly mark the existing flood lines, low-lying areas, high tide and low tide lines, and so on to ensure that the land use reservations do not contradict or undermine these areas.

The proposed land use (PLU) in the plan shows a fair number of green spaces but their ownership, usage and accessibility are masked with a single shade of green. The shortfall on land allocation for public utility allows for few recreational spaces, open spaces and sporting facilities in the public domain; those that exist are private clubs. Open spaces allow for the percolation of rainwater which helps to prevent flooding and to recharge the natural aquifers, but these are not reflected in the development guidelines for open spaces. Moreover, the inclusion of parking lots (Belapur Sector 13) and swimming pools (DY Patil Sports Stadium in Sector 7, Nerul) create an illusion of open space.

Then, the DP dilutes reservations on public space which helps to green-wash it. The PLU maps show parks, gardens, recreational grounds, stadium, tree-belts, open spaces all under a single category of PG/RG (playgrounds/recreational grounds). This makes the mapping ambiguous and is likely to lead to misinterpretation or conflicts as these areas have different legal designations or protection. For instance, the DY Patil Sports Stadium is a private facility, inaccessible to and unaffordable by the public. Similarly, playgrounds of private schools, shown here, are highly monitored inaccessible spaces.

Additionally, the factories in Rabale and Taloja pollute air and water with serious consequences on the health of residents. They also dump waste and effluents in Panvel and Thane creeks causing direct harm to the ecology leading to degrading mangroves and fish population which, in turn, impact the already vulnerable fisherfolk. Some of these areas may be located beyond the NMMC but they impact lives in Navi Mumbai. Such climate and environmental impacts transgress boundaries making it necessary that the DP addressed both city and regional planning.

Whither flamingo city?

The NMMC has made grand efforts to model Navi Mumbai as the Flamingo City as large flocks of the migratory birds nestle here every winter. The DP takes no note of this entire ecosystem and, in fact, proposes an 18-metre-wide and 35-kilometre-long coastal road from CBD-Belapur to Thane along the coastal stretch of the city.

This road will wipe out the entire ecosystem including large dense swathes of mangroves, wetlands, mudflats, and grasslands as well as open the area for further construction and ‘development’. Instead, the DP should plan buffer zones around such ecologically rich and sensitive stretches to conserve, protect and promote the migratory birds and other fauna. Despite receiving international recognition under the Ramsar Convention of Wetlands, proposed projects such as the coastal road disregard the importance of these wetlands. From Mumbai’s coastal road experience, it is known that such projects can cause massive ecological disruptions and are inherently “maladaptive” to climate risks.

People’s Right to Environment includes space too. When CIDCO developed housing in the then nascent Navi Mumbai, it went in for low-rise building with proportionate open spaces incorporating the neighbourhood concept. This housing stock is on the verge of being redeveloped. The newly introduced Unified Development Control and Promotion Regulations (UDCPR) permit high Floor Space Index (high-rise) redevelopment which would mean high population density on a small land parcel, causing pressure on the existing infrastructure as well as on natural resources.

Photo: Raju Kasambe/ Creative Commons

The way forward: Climate just city planning

In the DP, land use under the category of environment only includes four sub-categories: PG/RG, water bodies and creeks, mangroves, and forest. This is a simplification of complex environment into broad categories which glazes over their role in maintaining ecological balance. Equally, such categorisation of land parcels makes it easier to convert them piece-by-piece into urban plots for ‘development’.

A way out would be to carry out a comprehensive value assessment and clear sub-categorisation of ecologically sensitive areas. For instance, the value of vacant lands in ecological terms is higher than its land price alone; they should be sub-categorised as grasslands whose dependent flora and fauna need to be conserved. Natural assets like mangroves, wetlands, salt-pans, creeks, water bodies, forests, beaches, rivers, hillocks must be clearly demarcated as “protected spaces” in the ELU and the DP.

Navi Mumbai needs to have a hierarchy of open spaces with each having a different degree of accessibility. The ELU should analyse open space requirements at different hierarchies – local, ward, and city levels – and maintain their integrity while making land reservations. This will enhance people’s accessibility to open spaces and directly touch on their Right to Environment.

It is, by now, well accepted that Climate Change impact on health and livelihoods affect urban poor disproportionately and unequally. However, they have been erased from the city’s planning process. The Navi Mumbai’s DP does not identify a single urban poor settlement. Many of them are precariously located in low-lying areas, along nallahs and hill slopes, which are frequently affected by floods and landslides. During a climate hazard, the lack or low availability of health, transport, and water infrastructure in these areas make residents more vulnerable.

The urban poor living in such settlements also lack access to climate risk reduction information, and are less prepared for adaptation. Any climate adaptation programme should be linked with social security and equality. In the context of DP, the PLU maps should integrate disaster planning along with provision of social amenities in slums. The steps that the NMMC has taken so far to combat Climate Change impacts must be holistically addressed for the future.

The DP is as an opportunity to link climate adaptation with land use planning; it should not be a lost opportunity and must further integrate into regional and state plans. The DP sets out a land-use plan for the next two decades. It cannot be unmindful of Climate risks that Navi Mumbai faces; it must mainstream climate action. This calls for integrating environment with other sectors such as planning, policy-making, budgeting, and implementation. Climate Change impacts are layered and multi sectoral; they cannot be ignored in the process of city planning. Mainstreaming Climate Change into city plans would go a long way to ensure that people’s Right to Environment is protected and actualised.

Dulari Parmar, a Project Associate at Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA), has experience in community-led mapping. Her work focuses on climate justice in coastal cities. She extends her gratitude to Marina Joseph and Manasi Pinto from YUVA, for helping shape this essay with their critical inputs.

Cover photo: Kartik Mistry/ Creative Commons