In 1983, the Rural Litigation and Entitlement Kendra, a non-governmental organisation with its headquarters in Uttarakhand, wrote to the Supreme Court complaining about the quarrying being carried out in the Mussoorie region of the Himalayas. Landslides had devastated the area and killed locals when the hillsides were blasted. Five years later, the Supreme Court held that all the mines in the area, barring three, should be shut down. Mining in the valley had violated the Forest Conservation Act; economic development could not come at the cost of environmental degradation, it held.

This litigation led to the passing of the Environment Protection Act, 1986. It was the first case where the apex court had applied the concept of sustainable development. The landmark judgment upheld the environmental rights in India, citing that the Constitution of India guarantees the right to wholesome environment as a Fundamental Right under Article 21, the Right to Life, which also encompasses the less-discussed Right to Environment.

The Right to Environment, now universally accepted as part of human rights, are interpreted through rights to health, food, clean water and air. Its international roots, in the material sense, lie in the famous Stockholm Conference of 1972 during which the United Nations recognised that addressing certain environmental problems called for international cooperation. The Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment stated: “The right to a healthy environment is crucial as cities are facing the effects of air and water pollution. As more and more people are suffering from diseases owing to pollution, it becomes important to effectively implement the right.”

India responded with an amendment to the Constitution in 1976 in which Articles 48A and 51 A (g) were written explicitly for environmental protection. Article 48A comes under the Directive Principles and instructs the State to protect the environment. Article 51A (g) states that “It shall be the duty of every citizen of India to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife and to have compassion for living creatures.”

Fifty years later, in July this year, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution recognising the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a human right (Resolution 76/300).[1] This follows similar resolutions adopted by the UN Human Rights Council and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe last year, and has been deemed a “catalyst for accelerated action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals” by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment.

The recently concluded COP27 too stressed “the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and livelihoods”.

Photo: Eric Parker/Creative Commons

Inalienable but has to be claimed

The debate about the need for the Right to Environment has been settled; it is difficult to deny or erase the right now. Whether directly stated or indirectly inferred (as in India), it is now accepted as an inalienable part of human rights. A healthy environment is necessary for the overall growth of human beings.

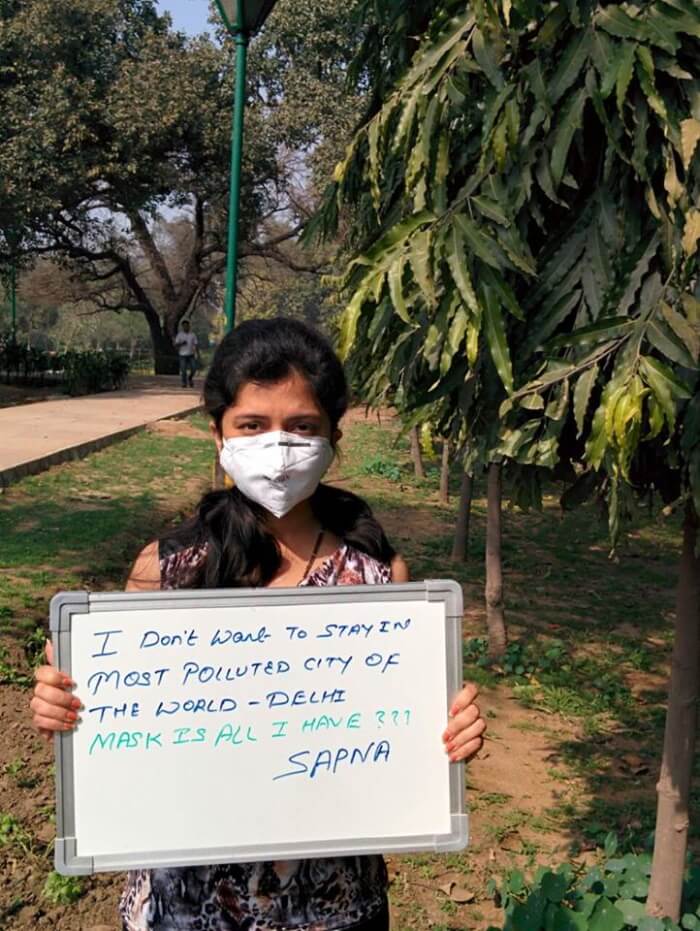

As cities are built and expanded on the profit-motive, the natural ecological balance is disturbed and the relationship between people and nature slowly weakens. The impact is all around – poor air quality, polluted water, congested spaces all of which affect people’s quality of life and are even responsible for deaths. Failure to secure environmental rights has meant that people in the land-locked northern India breathe highly toxic air every winter and millions struggle to get clean drinking water or adequate space in cities across India. Polluted cities and increasing deepening of Climate Change impact strike at the very root of our Right to Environment.

The latest Lancet Commission on pollution and health report blamed pollution for nine million deaths globally. It noted that India – where bad air kills more than a million people every year – was among the worst affected leading to an estimated 1.6 million deaths in 2019. The overall pollution-related deaths,[2] at 2.4 million, were also the highest in India; this includes water, lead and occupation-related pollution, the report pointed out. A majority of these deaths were caused by Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2.5) pollution, it added.

Activism to claim the right, crushed by violence

Like all rights, it does not mechanically or inevitably manifest in people’s lives; it has to be fought for and claimed, often through long-lasting protests or extreme action which more often than not brings on the might of the State on the protesters. The right has been invoked and tested through the bevy of laws on the environment enacted over decades, on the basis of which environmental activists and civil society have repeatedly approached courts.

This claiming of environmental rights, explicitly or otherwise, lies at the heart of many battles that the civil society has fought in the past few decades, often knocking on the doors of the Supreme Court to stall projects that could damage the environment, disturb ecological balance, and compromise lives.

Ideally, the State should enforce the right; when it does not, people are pushed to fight the State and claim the right in protests that have often turned violent – violent against nature as in Mumbai’s Aarey forest where more than 2,000 old trees were hacked in 24 hours in 2019 to make space for a metro car shed or in places like Thootukudi where 13 protesters were killed and more than 100 injured in 2018 in police firing as they raised voices against the pollution and excessive emissions from the Sterlite Copper plant.

As many as 200 environmental activists were killed in 2021, according to the non-profit Global Witness which tracks such attacks; Latin American nations ranked at the top of the list.[3] According to the UN, three people a week around the world are killed in their fight to protect environmental rights, with many more being harassed, intimidated, and criminalised for their essential work (UN Environment, 2020). Though Mexico, Brazil and Colombia were the deadliest places for environmental activists, according to the Global Witness report, India was among the handful of nations where violence against environmentalists had increased most markedly in recent years. As elected governments side with big business against the interests of nature and people, the battles turned intense and are likely to escalate.

“The most important is Article 21, the Right to Life, and that includes a clean and healthy environment. When the executive fails, the court has to step in,” says Vivek Chattopadhyaya, principal program manager of the air pollution control programme, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi. Article 21 is the responsibility of both the central and state governments, but if the government does not do its duty, people have the right to sue the government. And the right to protest.

Photo: Creative Commons

Poor implementation of law

The Right to Environment is reflected in a host of laws enacted from time to time — The Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, the National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, and the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974. They make it incumbent on the State to protect the environment but people have had to drag the State or corporations to court instead. Even on occasion that the judicial orders have been in favour of nature and people, their implementation on ground has remained tardy.

In 1996, while hearing a petition filed by Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum, the Supreme Court passed an important judgment. Citizens had filed a petition against the untreated effluents released by tanneries which polluted the Palar River, the main source of water in the area. Deciding in favour of the petitioners, the court observed that the tanneries were a health hazard to the people. This judgment sought to ensure a healthy environment and stressed on sustainable development; however, it did not fully reflect on the ground.

“It doesn’t matter what the court has said and not said. You just have to look around to see its impact. If the Right to Environment had been strictly enforced, then the country would look different – whether the pollution control is doing its job, whether the Environment Ministry is relevant, and whether the courts are able to play the role of a positive force,” says Chennai-based environmental activist and writer Nityanand Jayaraman.

It has been a chequered journey, a mixed bag, with the numerous progressive judgments on the Right to Environment since the 1990s; they are important but they did not always check environmental damage.

Special ecological tribunal

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) was established under an Act in 2010 to dispose of environmental protection cases, conserve forests and other natural resources matters. It was also meant to enforce legal rights relating to the environment, and giving relief and compensation for damage to person or property, according to its establishing law. With the NGT structure, India became the first developing nation and the third country in the world, after Australia and New Zealand, to have a specialised ecological tribunal.

The NGT has passed numerous orders in these years that have upheld the ecological integrity of an area, but has come under criticism for its relative powerlessness to have them implemented. “The NGTs are technical forums. It passes orders but it does not look at it from the governance perspective. Though it is a judicial body, the NGT does not have the teeth like the SC or high courts,” says Soumya Dutta, trustee of MAUSAM (Movement for Understanding of Sustainability and Mutuality).

The NGT order of January 13, 2015, on the Yamuna River was significant but the restoration project has missed numerous deadlines. The river continues to be in a pathetic polluted condition. After the petition by Manoj Misra, convener of Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan, the NGT bench presided over by chairperson Justice (retired) Swatanter Kumar issued 28 directions for the implementation of the ‘Maily Se Nirmal Yamuna’ rejuvenation project by March 2017. The bench levied a fine of Rs 5,000 on anyone spotted throwing waste in the Yamuna, and a fine of Rs 50,000 for dumping of construction debris.

“The directions were significant but nothing came out of it. The problem with the NGT is it has no power of contempt,” says Misra, adding that the provision to jail offenders has not been used. Adds Chattopadhyaya, “The tribunal should be further strengthened – give it more powers, equip it with expert members.”

The NGT was severely criticised for its inconsistent judgment in the petition against Sri Sri Ravi Shankar’s Art of Living Foundation which had organised a three-day cultural event in March 2016 on the Yamuna floodplain. Before the festival, Misra petitioned the NGT to stop the event as it would damage the floodplain. The Tribunal had failed to stop the event despite the environmental consequences. Later, it held the Art of Living Foundation responsible for the damage and imposed an environmental compensation fine. Irrespective of whether the amount was paid, in full or not, the pollute-and-pay one’s way through would hardly help in ecological conservation or upholding people’s Right to Environment.

Photo: 350.org/ Creative Commons

Striking a balance

Four and half years later, the Thoothukudi[4] case presents a piquant issue that must be playing out in many locations around the country: the hard choice between jobs at polluting industries and clean environment to live in. Many, including those who were injured in police firing, want the plant to reopen as they grapple with the loss of jobs and livelihood.

Caught between exercising their Right to Livelihood and Right to Environment, locals seem to have chosen the former given that families suffered without jobs. But they should have never had to make this choice. It is not a choice at all – a clean environment without livelihood holds little meaning, jobs without a clean environment adversely affects their lives.

This points to the limitation of having the right and the laws with which the right can be exercised. “Not law, but culture, can play an important role in ensuring a clean and healthy environment. In order to have a healthy environment we need to have a culture which values the environment,” says Jayaraman.

Three years after India passed the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1981, the Bhopal gas leak happened. “The Act did not protect the people of Bhopal. The regulatory collapse prevailing in the 1980s is no different now. There is no change in regulatory discipline,” says Leo Saldanha, coordinator of Environment Support Group, a Bengaluru-based NGO which works on environmental and social justice initiatives.

Saldanha shared the example of the London Smog of 1952 which killed more than 4,000 people and many suffered respiratory ailments. This prompted Britain to pass the Clean Air Act in 1956; air pollution is taken seriously and countermeasures are still being put in place. “What is the purpose of having such jurisprudence that doesn’t deliver in real terms? We need a structural change as India’s nightmares will be worse than other countries,” says Saldanha.

In 2019, the Government of India launched the National Clean Air Programme but Indian cities regularly occupy the top ten or more spots in the list of all cities in the world. Stringent environmental laws alone will not improve air and water quality, or make open space available to people.

People have to be aware of rights – specifically the Right to Environment and what it means in our lives – and fight the good fight. The rights exist, the legal routes to establishing and claiming those are there too. When the State appears to have abdicated its role as protector of the natural environment, people have to step up to see it as a trans-disciplinary issue and take action. Otherwise, the Right to Environment as part of Right to Life will be redundant. As Dutta puts it, “If Delhi’s residents lose nine years of their life on an average due to pollution, where is their Right to Life?”

Shobha Surin is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An associate editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: Adam Cohn/ Creative Common