Forty years ago, the issue of housing of the vulnerable and poor in the city came to the fore in the most shocking manner. The monsoon of 1981 saw massive demolitions of slums and pavement shanties across Bombay, the bulldozers turning the apology of houses into rubble, decimating the meagre belongings of the poor, bundling them with their little children into trucks and police vans to be carted away to the margins of the city – sending a message that they were not welcome. The words “demolition drive” sent shivers down the spine of those who could not afford permanent or better accommodation.

The political class and the middle class saw slums as “dirty” and “unwanted” in the city and slum dwellers or pavement dwellers as “encroachers” of precious commercial land. Little thought was given to the fact that the millions who occupied slums serviced the city in myriad different ways – as maids, drivers, workers, carpenters and plumbers. The irony that cheap shelters they were forced to live in lowered the service costs was lost on the elite, who mocked them and wanted them evicted.

On the ground, this translated into a series of inhuman demolition drives from 1980 onwards. The state government, led by chief minister AR Antulay, had more sinister motives: he targeted slums on prime land like in Nariman Point and other lucrative south Mumbai areas. The government and politicians were stepping in for builders, the poorest in Bombay were paying the price.

These demolition drives, inhuman and questionable, threw up resistance of various types: Legal, remedial, and activist-advocacy. The severe housing shortage and the inability of the government to address it made shelter a burning issue. Bombay, and Maharashtra, became a laboratory or a crucible of action against the inhumane demolition as well as the early articulation of housing as a right. This expanded to other cities and states later.

Several organisations of slum dwellers sprung up to protest and demand better from the government, enraged sections of the civil society grouped to articulate and amplify the voice of the slum and pavement dwellers. The early 1980s saw journalist Olga Tellis and the Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights (CPDR) file cases in the Bombay high court to get a stay on the forcible eviction of pavement dwellers. Advocates Colin Gonsalves and PA Sebastian brought their professional expertise to the issue, some of us from youth organisations – inspired by the Naujawan Bharat Sabha which identified with Bhagat Singh – became part of this work. Nearly 30 organisations came together under the banner of Nivara Hakk Saurakshan (later Suraksha) Samiti.

Nivara Hakk began as a collective, an umbrella organisation of the groups and people involved in the struggle for housing rights, and remained that for years before it was formalised. It was representative of grassroots slum groups as well as middle-class advocacy organisations. Its street-level resistance – the ability to bring out thousands of slum dwellers for dharnas and morchas – made the state government take notice.

The guiding principle behind Nivara Hakk was – and remains – that decent and affordable housing is a right of all citizens and it should be claimed from the state. Towards this, different means have been used – street agitations, demonstrations at demolition sites, morchas to government offices, advocacy among slum dwellers, legal work, and support to slum dwellers to undertake self-development of houses at alternative sites like Sangharsh Nagar.

In these four decades, the issue of housing has been foregrounded, even centralised, in the discourse on urban rights or right to the city.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

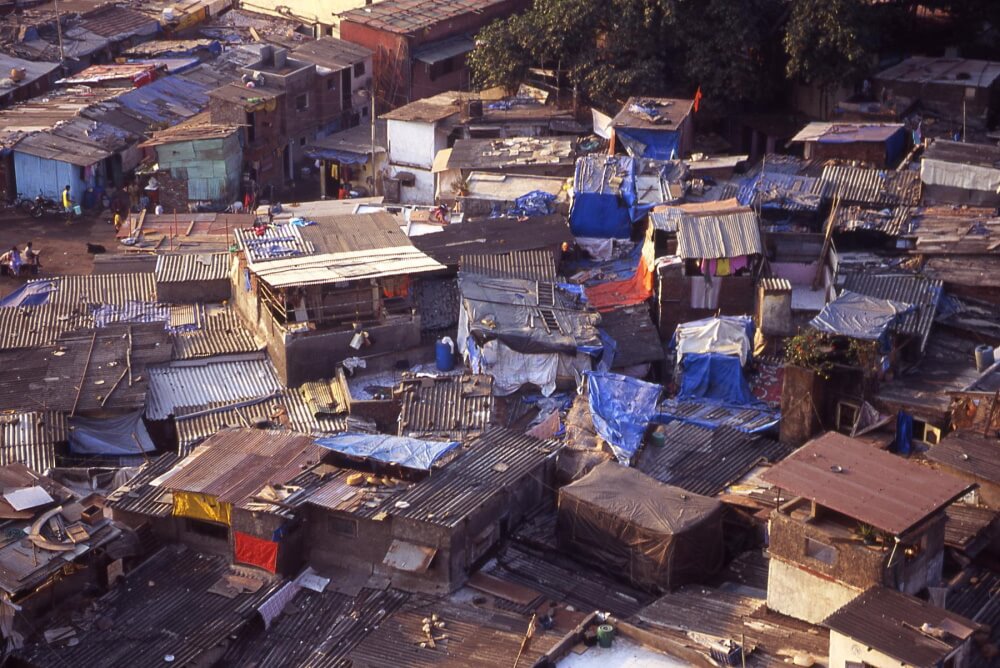

Sanjay Gandhi Nagar slum

The housing struggle in the early 1980s was personified by the battle waged by the Sanjay Gandhi Nagar slum dwellers. This slum with nearly 350 families, on prime land near Mantralaya in south Bombay, was threatened with demolition. It was opposite the multi-storey complexes where IAS officers lived. Most of the staff in these towers came from the slum. In fact, the domestic help in the house of the then housing minister, V Subramanian, lived in Sanjay Gandhi Nagar but the irony escaped the minister. Nivara Hakk was working in the slum as social worker Anna Kurian had set up a school and a creche. When the bulldozers rolled in, people reached out to us.

Around the time that the slum was facing demolition, filmmaker Anand Patwardhan was in Mantralaya to show his documentary “Bombay, Hamara Sheher”. Shabana Azmi, there for another meeting, happened to watch it too – and was moved. She joined the hunger strike at the slum; she had come with only the clothes on her back but the Bollywood star sat there for 10 days. Her spontaneous act of support turned into a long association whereby Shabana Azmi became the face of Nivara Hakk and the struggle for housing rights.

Nivara Hakk had organised massive morchas, street protests with plays and songs, demonstrations at Mantralaya to push for housing as a right, beyond the demolition drives. It was constructive and went beyond anti-demolition protests. Other groups worked on advocacy and in legal forums. In 1985, during the Congress’ centenary year celebration in Bombay, the state government was keen that demonstrations and hunger strikes did not go out of hand. It changed the law to give squatters rights with the concept of a cut-off date or year. Those who could prove that they had settled in slums before 1980, later extended to 1985, could claim rehabilitation though at a different site.

Most migrants in the Sanjay Gandhi Nagar slum had come just after 1980 and were not eligible. The government wanted the land for a fire station but builders were also interested in the prime plot. The battle had to be fought on the ground. Violence ensued, barbed wires went up, heavy police presence marked it out, Anand and Shabana’s hunger fast drew attention of the media, and a child died in the retributive police action. The prime location, involvement of activists and celebrities, State violence, relentless protests – the fightback led by Sanjay Gandhi Nagar Rahivasi Sangathan and backed by Nivara Hakk – made it a symbol of the 30 to 40 slums being demolished across the city.

Role of the courts

The courts, both the Bombay HC and the Supreme Court, were part of the story on housing rights. The HC said that a citizen’s right to life included their right to livelihood, and demolishing their place of residence could adversely impact their livelihood. An initial order of stay by Justice Lentin of the Bombay HC provided immediate relief to lakhs of pavement dwellers facing eviction. However, the final SC judgment said the right to walk on a pavement superseded the right to shelter. Chief Justice YV Chandrachud made poetic references to women bathing on pavements being a blot on humanity, but asserted that pavements were public property and not meant for housing. The judgment did make general references that the state should provide affordable housing to those without shelter but no process was laid out.

Street struggles, therefore, continued though there were debates on tactics. Many groups in the Nivara Hakk collective went their own way. Some like YUVA, who disassociated themselves, continued work on the issue through awareness-building. Eventually, with the remaining three-four groups Nivara became an organisation in 1986-87. Our fight on Sanjay Gandhi Nagar had expanded to a broader struggle on housing in the city, housing as a right which put the onus on the state to provide affordable housing, a right which could be claimed by the poor.

Meanwhile, the struggle of the Sanjay Gandhi Nagar slum residents bore fruit by 1986. The Maharashtra government offered the residents a three-acre plot in Goregaon for rehabilitation. It was barren land, Nivara Hakk helped to level it, and PK Das designed the housing community with low-rise buildings, common amenities and open space. The fight was for rehabilitation in situ, but the Sanjay Gandhi Rahivasi Sanghatana and we agreed that the new site offered secure land tenure which was not possible in Nariman Point.

Photo: Creative Commons

Housing rights movement

The sharp street battles and broader struggles through the 1980-90s were triggered partly because the city had the most expensive real estate in the country and commercial stakes were high. Asserting the right to housing was, therefore, equally important especially for the poorest; Nivara Hakk was a key part of the movement, indeed.

Broadly, this movement can be seen through three phases. The first was the initial phase in which poor people’s right to shelter was fought for and recognised in law so that there would not be summary evictions. The second phase was when the government and the municipal corporation had recognised slum dwellers in law but left them to their own devices in unhygienic conditions which spurred Nivara Hakk (and other organisations) to get them to provide basic civic facilities such as water, sanitation, and so on.

An example would be the National Park case, coincidentally also named after Sanjay Gandhi. Through the early 1990s, the borders of the National Park were occupied by thousands of new migrants – the last big wave into Mumbai. Politicians and slum mafia made hay “selling” land and settling them here. As demolitions continued, slum dwellers from other areas and new migrants to Bombay went to the area too. These slums, with a high Muslim population, were targeted during the communal riots of 1992-93 and Nivara Hakk joined the work to provide relief supplies. Eventually, we were drawn into the housing struggle when environmental organisations filed petitions in the Bombay HC to demolish these slums.

What followed was a unique struggle of thousands of slum dwellers. Resistance and marches combined with media campaigns, court cases and negotiations with the government from 1998 onwards resulted in the creation of Sangharsh Nagar in 2007. The Congress’ Vilasrao Deshmukh government agreed with the court that those who had houses in the National Park before January 1995 would be eligible for re-housing. With Nivara Hakk’s oversight, a slum rehabilitation project under the government’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) was approved in Chandivali for a massive 90-acre layout. As many as 14,000 families already have 225 square feet tenements and 8,000 more families are waiting for theirs. There are problems galore but Sangharsh Nagar – a layout of over 300 buildings in over 25 clusters – represents the success story of grassroots movement for housing rights.

There was the third phase of the struggle too. In the post-liberalisation years, the trajectory of ‘development’ became an issue of debate. Slum Redevelopment Schemes and the Slum Redevelopment Authority had emerged. The approach was to hand over slum plots to builders, have them provide slum dwellers with houses in multi-storey buildings free of cost, and allow them to develop saleable high-end apartments to recover investment. Such SRA projects became the rage as slum committees became power brokers for builders and slum dwellers who nursed aspirations of “living in a building” supported them.

So, in the third phase Nivara Hakk turned to education to convince slum dwellers that this might not be in their best interests, supporting the section that wanted to redevelop the slum themselves. Nivara Hakk tried to make it work in Sanjay Gandhi Nagar, the resettled colony of people from Nariman Point. If they self-developed, each family could get 500-600 square feet homes with common area amenities for all 350 families but they would have to take individual loans and responsibility. The builder was offering them Rs six to eight lakhs as well as a free 225 square feet tenement. They went with the builder.

Nivara Hakk then became a sort of a trade union, often helping slum groups negotiate with the builder for better terms. We see what stage of the struggle people are at, try and unite them, and get them the best possible deal. We also provided relief to earthquake-hit regions in Latur (1993) and Bhuj (2001), and worked on the housing issues there.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Housing movement in the housing market

The housing market in Mumbai has undergone major changes in the last 40 years. The SRA schemes meant that builders were roped in to provide houses to slum dwellers. It was lucrative but it came with political risks; now the market has stagnated and profits plateaued out. Then, slum demolition is not as frequent or shocking as earlier; so, the fightback has also declined. The relationship between the political class and slum dwellers changed; politicians need votes of slum dwellers and many politicians have turned real estate developers which meant eviction was not an option.

Over time, Nivara Hakk’s role too changed. From street fights and struggles to ensure slums are not demolished, we focussed on slum improvement and re-housing. Besides engaging with the government and municipal authorities, we set up balwadis and vocational centres in slum communities. The Goregaon vocational centre, for instance, has trained thousands of young people as beauticians, in computer and sewing skills guaranteeing them a monthly income of Rs 15,000-25,000 each.

The focus is now on improving the conditions in slums, ensuring that finance is available if slum dwellers want it, and reducing builders’ involvement. This market calls for government bodies like MHADA to fund slum dwellers for self-development. Otherwise, we are looking at a massive scandal of land as in the BDD Chawls case where more than 60 per cent of the area is being taken over for upper class housing, as highlighted by town planner Shirish Patel and others.

Looking back, Nivara Hakk was shaped by the situation in the 1980-90s: We plunged into the issue, went where we were called to help to stall demolition, used street fights and confrontation with the government to have housing recognised as a right. We also had hundreds of grassroots meetings with slum dwellers, placed stories in the media, communicated with stakeholders, and more. Nivara Hakk realised that securing rights is a process of both movements and negotiation, both have to be done.

Politicians are more receptive now to issues of housing as a right, at least on the surface. Remember the declaration of 40 lakh free homes by the Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray in 1998? The ‘free’ homes were not built, but the promise helped the party win elections. Now, no politician wants to be seen as anti-slums, but decent and affordable housing is still not a reality for the majority. Winning housing rights is an unfinished struggle and will remain so for a while.

Gurbir Singh is a senior journalist and works as a Consulting Editor for The New Indian Express. He is also one of the founding members and an office bearer of Nivara Hakk Suraksha Samiti.

The cover photo shows a child looking at the remains of his house, which was razed for widening the Mithi river in Mumbai. The Bandra Kurla Complex, a posh area on the other side of the river, though on encroached land, is untouched.

Photo: Joe Athialy/ Creative Commons