Lalit Dulal, 25, remembers that catastrophic day as if it was yesterday. He was in Melamchi Bazaar when he came upon the devastating flood sweeping away stones, logs, and cowsheds on June 15 two years ago as the Himalayan glaciers melted and brought down a torrent. “We got to know that the Melamchi River had flooded. My family and I moved to a safer place. The incessant rain showed no sign of stopping; the entire Melamchi Bazaar was destroyed,” recalled Dulal.

His house was far from the river, so it was not washed away. “However, my maize and vegetable crops cultivated on roughly 0.126 acres were destroyed. Even the tractor used for farming was submerged,” he recalled. Rudra Kumari Shrestha, 30, was less fortunate; she helplessly watched her house on the top floor in Rudreshwar Higher Secondary School’s compound collapse. “Floor by floor, the entire house sank; all my property was gone in a few minutes,” she cried. Melamchi has not been the same again though life is slowly trickling back to pre-flood normalcy.

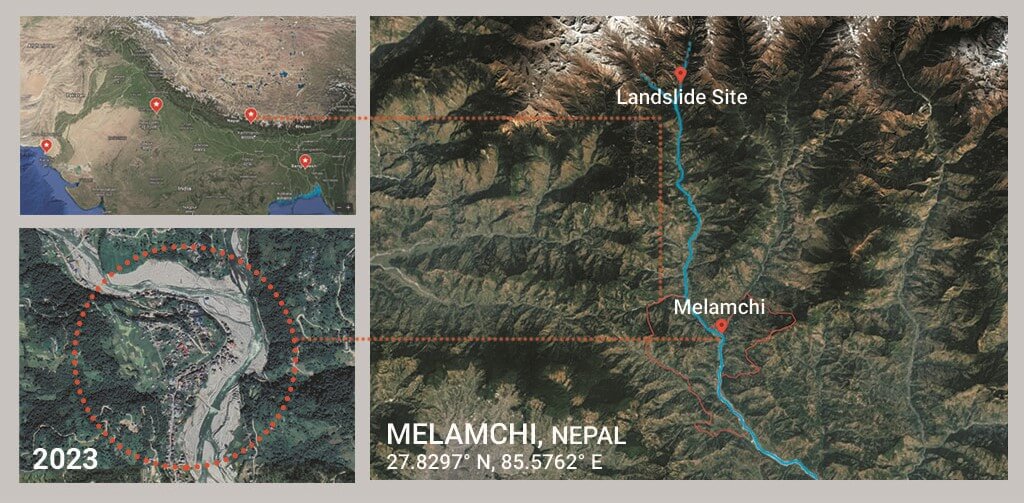

Map: Shivani Dave

The unprecedented flood in the Melamchi River, 41-kilometres long which originates in the Jugal Himal range and joins the Indrawati River at Melamchi Pul Bazaar, severely damaged its ambitious water supply project. Counted among the national pride projects[1] and built with international funding to supply 170 million litres a day to Kathmandu, it had been nearly three decades in the making but operational for only a year. It had not budgeted for Climate Change impact.

Located around 76 kilometres from Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal, Melamchi in Sindhupalchok district was a small town in the 1990s when the project took off the ground. Now, Melamchi faces multiple hydro-meteorological hazards and the inevitable impact of rapid urbanisation which precipitated environmental degradation. The risks are now extending to the upper reaches of the Melamchi River, jeopardising water supply to Kathmandu especially during heavy rainfall and floods.

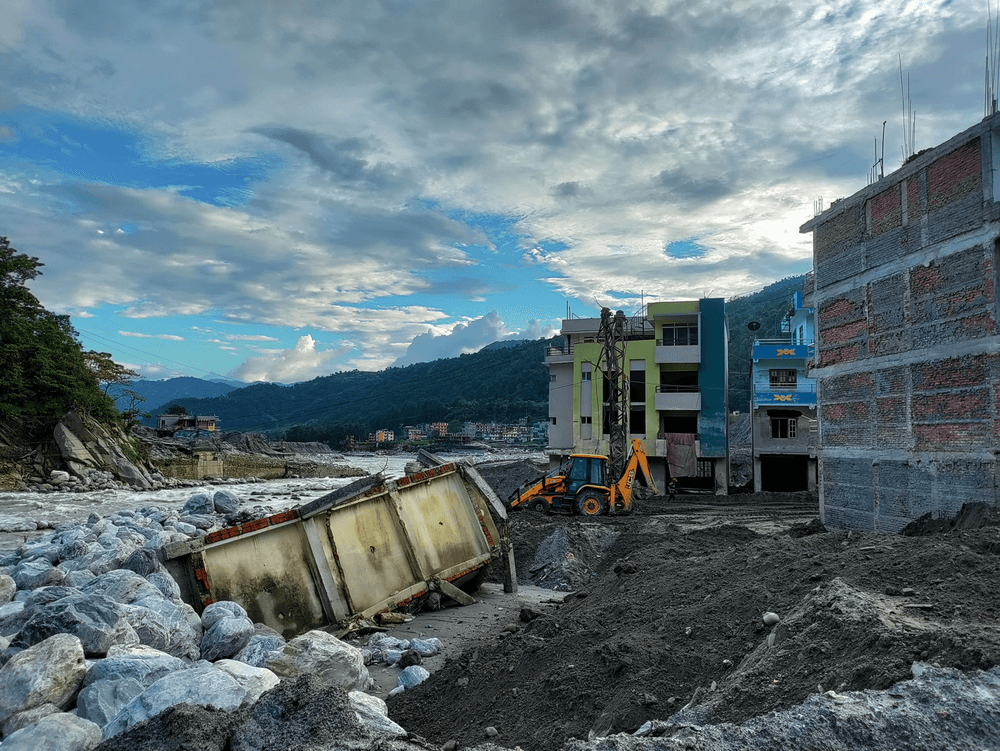

Photo: Dipen Dhungana

Growth marred by disasters

The history of Melamchi dates back centuries to the Rana dynasty. The town was on the Kathmandu-Tibet route, and remained quiet and quaint for years. As the Melamchi Water Supply Project (MWSP) gained ground and work opportunities opened, people began settling here. Schools, hospitals and other infrastructure expanded. Soon, Melamchi had turned into a centre of attraction in the district, and Melamchi Bazaar became a thriving business hub with hotels, lodges and handicraft businesses catering to tourists passing through the town.

The town comprises Mongolians, Aryans and other ethnic groups living across its 13 wards. The major source of livelihood is agriculture and animal husbandry and dairy business; its growing economy has focused on commercial farming by setting up pocket areas. Besides agriculture, Melamchi’s recent prosperity has been driven by tourism (tourists heading to Gosaikunda, Helambu, Panchpokhari), industry and watershed[2]. However, “the devastating earthquake of 2015 brought Melamchi to a complete standstill. As it was slowly bouncing back, the unprecedented flood in 2021 pushed Melamchi into further misery,” said Dharmakrishna Shrestha, a septuagenarian businessman here.

The Melamchi Municipality took its present shape in 2017 when four neighbouring village development committees (VDCs) of Bhotechaur, Haibung, Thakani, Dubachaur and a part of the Shivapuri National Park were incorporated. The Municipality witnessed[3] rapid population growth since 2011, at 5.2 percent per annum. Melamchi Bazaar became the business and service hub. Its fortunes saw a dramatic turnaround with the June 2021 flood as many lives were lost and massive damage to infrastructure ensued. Minesh Gurung, project officer at Practical Action Nepal working in Disaster Risk Reduction field, noted that Melamchi has always been at risk of multiple disasters including earthquakes, floods, landslides, fires, lightning, and glacier melting and glacial lake burst.

The conversion of vast areas of farm land[4] into housing plots, driven by rapid urbanisation, has been increasing in Melamchi. The trend of land transactions has increased land subdivisions and sprawl. Thirty-seven percent of the municipality was forested[5] in 2017; it would have declined. To add to this, haphazard construction of roads and the expansion of settlements has put a strain on the natural environment. In recent years[6], the number and scale of operation of stone crushers and sand mining has increased dramatically along the Indrawati River.

Horrendous floods, sign of future

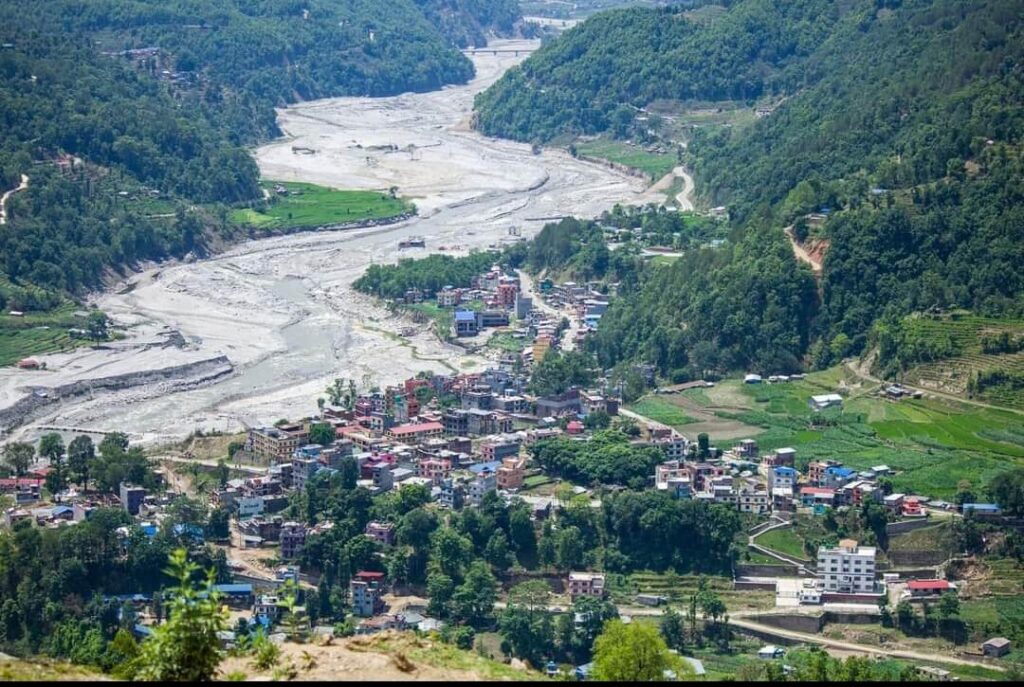

The Melamchi River watershed receives more than 1,200 mm of rainfall during the monsoon every year. Extreme precipitation events and associated hazards continue to occur; these are compounded by Climate Change as witnessed during June and July 2021 when it not only rained massively but flood water engulfed parts of the town. The flash flood on June 15 followed by a recurring flood the following month devastated 255 households, two concrete bridges, two suspended bridges and thousands of hectares of agricultural land, bringing the entire town to a dead halt for several weeks. Large parts of Melamchi were covered in rubble and thick mud, thousands of trucks were needed to clear it.

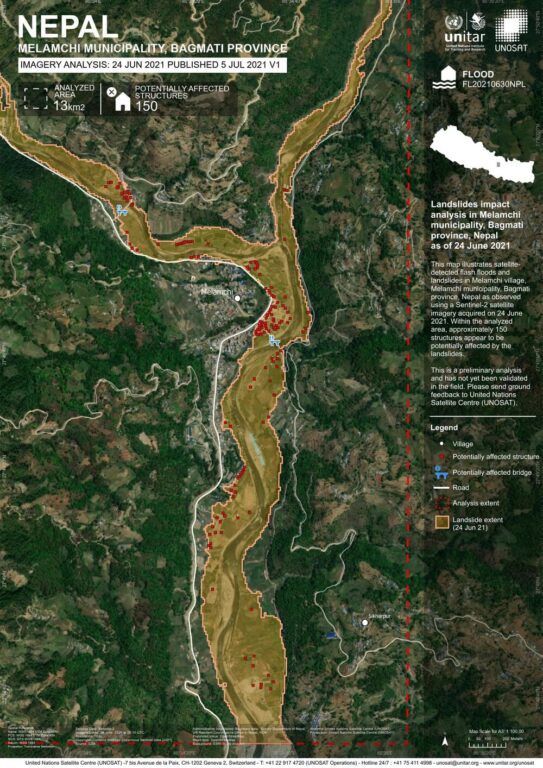

Map: Shivani Dave

Researchers are still investigating the causes of the devastating flood and the contribution of different factors but most research offers the view that the massive disaster was the result of a series of compounding events. A study by ICIMOD[7] in 2021 on the Melamchi Flood Disaster attributes its cause to multiple processes along the Melamchi River including massive 21 million metric tonnes of debris dumped in the upper part of the Melamchi River; of this, four million metric tonnes trickled down during the flood which means that the remaining is lodged in the upper part of the mountain region around Bhemathang. Therefore, the danger is not over yet. The ICIMOD study too says so.

Ranjan Kumar Dahal, a leading geologist and climate researcher who studies Melamchi area, confirmed[8] that around 15-metre-high debris has piled up at the Melamchi Water Supply Project site and the clean-up work could cost Rs 300-350 million [about £1.8 million USD?]. “The floods damaged the roads and bridges to the project site and washed away the campsite and construction materials,” said Dahal.

Some studies[9] have indicated the overflow of the Pemdan glacial lake located upstream in Melamchi catchment which resulted in the destruction of the natural dam of the Bhemathang area, ultimately eroding the riverbed. The origin of this disaster can be traced to, among other factors, the 2015 earthquake which triggered multiple landslides in the Melamchi River catchment increasing its susceptibility to slope instability. Another noticeable factor, linked to Climate Change was the perceptible five to nine degrees Celsius rise in temperature that month which melted the glaciers and cascaded unimaginable torrents into Melamchi area[10]

Climate Change impact is written all over the calamity. Ichharam Sapkota, disaster risk reduction in-charge for Melamchi-based Community Development and Environment Protection Forum, attributes the flooding to unusual and sudden heavy rainfall in the mountains possibly triggered by Climate Change. “The impact of Climate Change is increasingly being felt across Sindhupalchok district with an unnatural temperature rise leading to rapid snow melting in the mountains. Heavy rainfall in high Himalayan regions has resulted in this flood,” explained Sapkota.

Photo: Dipen Dhungana

More responses needed

Climate Change impact was likely exacerbated by human interventions and urbanisation decisions. There was record-breaking pre-monsoon rainfall including in the usually arid regions which should have alerted authorities. Experts said that 60 percent of the rainfall occurred in only two weeks.[11] The day that Melamchi River burst was also when Chame, a district capital city, was massively flooded.

Human factors cannot be ignored too. The negligence of locals in adhering to construction guidelines played its part. Amrit Kumar Dhital, chief administrative officer of Melamchi Municipality, explained that “the UNDP report classified areas around the Melamchi River into high-risk red zone, low-risk yellow zone, and non-risk green zone categories. The flood washed away the red zone area resulting in damage amounting to 500 million US dollars.”

The mushrooming urban settlements with massive construction in the high-risk areas of Talamarang, Thulokhet and Melamchi Bazaar should have been strictly prohibited but the municipality failed to stop rapid and thoughtless urbanisation. People paid a heavy price for this: Municipality requested residents to comply with the rule but did not take strong action against violators.

Asha Khanal Shrestha, a 42-year-old hotelier, and her family lost her Melamchi Cafe Inn in the Bazaar as well as her agricultural farm nearby. “Our family has been living in Melamchi for three generations. We had never imagined that a flood of this intensity would ever occur,” said Shrestha, adding that the family had invested Nepal Rs 16 crore to build the hotel and paid 4.5 lakh in taxes to the Municipality – it went in a flash. “My husband cleaned the sediments and removed the water. Our request to the municipal authorities for an excavator was in vain…we still fear massive floods every monsoon,” she said.

Besides the municipal apathy, there was another disturbing aspect – the lack of disaster risk assessment and quick emergency response mechanism even in the high-risk areas. The Municipality, however, disagreed. Dhital argued that “the Municipality was constantly in action…We waived off charges for three months for people in rented houses, provided basic food for six months to all the affected.” However, people were “unwilling to migrate to safer places because they consider leaving their ancestral land a bad omen.” The key here – and Dhital agreed – is that the existing policies provide compensation only for people who lost houses but not their land or other property.

This highlights once again that Nepal has work to do on the disaster response and rehabilitation mechanism. Importantly, how and to what extent Melamchi – and similarly ecological-fragile places – can be urbanised should have become a focal point of debate. It is important to empower the local government with more human and financial resources and institutional capacities for effective disaster management instead of top-down strategies to combat such disasters.

Since that devastating flood, Melamchi has continued to face calamities. This August too, heavy floods disrupted road networks and caused agricultural damage showing that the one in 2021 – though massive – was not an exception. Melamchi is situated on one of the most geologically fragile areas of Nepal and carries great risks of earthquakes, landslides, and floods; this should have led the Municipality to devise short-term strategies along with comprehensive plans to address the crisis, and paid close attention to the urbanisation model adopted.

There are issues which transcend economic and infrastructure damage in a flood, such as people’s mental health. After June 2021, Melamchi witnessed a surge in suicide cases and people suffering from anxiety and depression. “Women, children and senior citizens have been severely affected. Children couldn’t attend school, women lost their land and had restricted mobility,” pointed out Asmita Aryal, officer of the judicial committee of Melamchi Municipality. In fact, deputy mayor Uma Pradhan called for analysing the disaster from a gender perspective, noting that during the 2015 earthquake as well as 2021 floods, women, children, and the elderly were disproportionately affected. “Men often leave villages for work, women bear all the responsibility,” she said.

A two-day psycho-social counselling session had been organised then but more needs to be done, she agreed. The Municipality had collected data to identify trauma-affected people and found that they had low self-esteem along with apprehensions or fear of “something wrong” happening. It also developed a communication strategy that involved regular door-to-door interaction with the women, children and elderly people, recreational activities like music and culture programmes including sessions on motivation and positivity.

Disaster governance and road ahead

Urban governance during such disasters has its roots in the provisions of the new Constitution of Nepal, 2015, which assigns disaster management to the concurrent right of federal, provincial and local governments. In cities, it would be the urban municipalities, with autonomous governing status, that are entrusted with the responsibility. However, there is scope for confusion and crossed wires – while local governments have the authority to deal with the Climate Change impact, disaster management is a shared responsibility. This has resulted in a muddle about policies, planning guidelines, and regulatory frameworks.

However, Melamchi Municipality was influenced by the June 2021 floods to form a team of scientists to assess disaster risks and propose short-term, medium-term, and long-term measures to mitigate future disasters. Towards this, the Municipality instituted building standards for settlements around Indrawati and Melamchi rivers, and identified alternative sites such as Bhattar in Talamarang, Tar in Melamchi and Paglipati to relocate settlements in the high-risk areas but has been unable to implement it.

Besides, it has installed three early warning stations to share flood-related information with people in advance to help them prepare, launched the Melamchi Flood Fund and mobilised resources from the federal government and community-based organisations for relief and reconstruction, set up the Emergency Work Operation Centre to report disasters and ensure a flow of disaster information, and formulated a monsoon preparedness and response plan mandated by the nodal National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority. Equally importantly, the Municipality evolved a school-college curriculum exclusively related to the environment and disasters to improve disaster awareness and preparedness.

The major challenge has been resources. Despite submitting a report to the federal government, the Municipality has to date not received funds for reconstruction in Melamchi. “While agriculture and social security sector easily receive grants from the federal government, a dedicated grant for disaster is absent,” pointed out Sujan Dulal. This has affected the rehabilitation and reconstruction work.

The authorities in Melamchi and Kathmandu could draw lessons from this experience about urbanisation in the context of Climate Change but significant discussions have not happened in this direction. The Melamchi flood disaster has left enough wreckage for Nepal to reflect upon about how its cities and towns should develop and expand.

Kushal Pokharel is an independent researcher and science communicator based in Nepal. His writings have appeared in leading national and international media outlets including research journals. His research interests span natural resource management, water security, Climate Change and development with a focus on public policy and governance. He also serves as a faculty of research methods and skills.

Chhatra Karki, a science journalist based in Kathmandu, Nepal, has rich experience in newspaper and online news portals. In recognition of his exceptional contributions, he was honoured with the Science and Technology Journalism Award from the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology in 2021. His expertise encompasses a wide range of topics including environment, Climate Change, science, health, and current affairs.

This is the first part of a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship to report on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia.

Cover photo: Melamchi Bazaar by Dipen Dhungana