The narrow dingy lanes in Cheetah Camp in Trombay, on the eastern edges of central Mumbai, are lined with tightly stacked rows of one-room kitchen tenements. A handful of two-storey houses tower over them. Some have managed to build small shops in front of their houses, further narrowing the lanes. This is a part of the M-East civic ward in Mumbai – one of the poorest places in India’s wealthiest of cities.

Visually, the M-East ward does not resemble Mumbai’s iconic landscape at all. In terms of amenities too, this area looks like a forgotten and ignored part of the city – its roads and footpaths broken, water supply wrecked, sewage overflowing, tightly-packed ‘homes’ that are hell holes, open gutters, dilapidated community toilet blocks, and more. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) is barely present here. Unkempt and deficient in every way, yet housing lakhs of people who run tiny businesses or work as daily wage labourers.

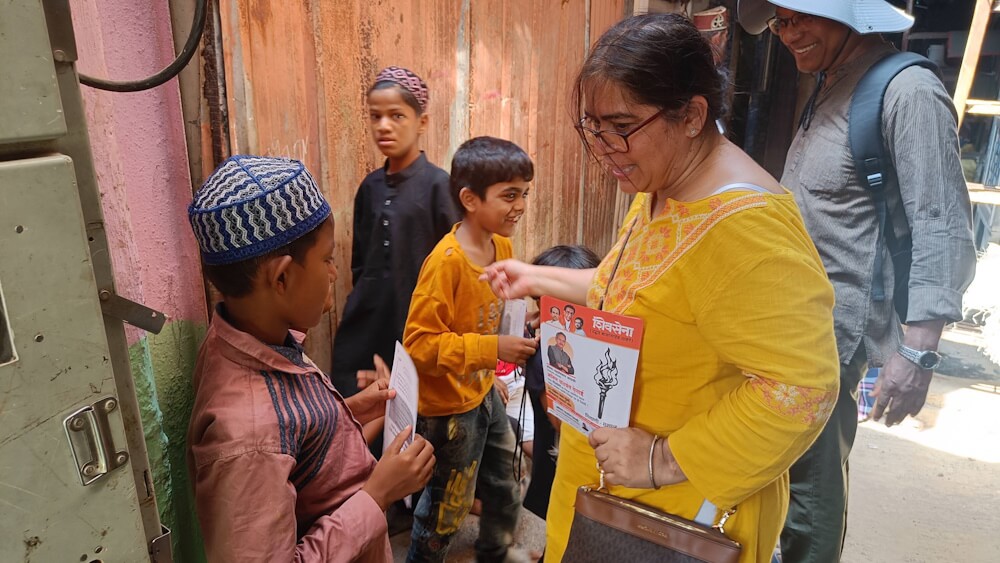

In the Cheetah Camp lanes, dodging the overflowing soapy water as women wash their family’s laundry in the open narrow lanes, Sabah Khan and her team trudge around distributing pamphlets of candidates. A former faculty member in the reputed Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Khan has been working in the M-East ward through the community organisation Parcham Collective. “Sabko vote mubarak bolkar aage lana hai, theek hai,” (Greet everyone and bring them forward to vote) says Sabah, drawing parallels with the familiar greeting of Eid Mubarak, given the large number of Muslims here.

The voting awareness is essential across the civic ward that comprises, besides Cheetah Camp, equally deprived areas such as Vashi Naka, Mahul, Lallubhai Compound, Deonar which is (in)famous for abattoirs and the city’s landfill, RCF Colony, Bainganwadi, Indian Oil Nagar, Shivaji Nagar, Milan Colony, Mankhurd and Govandi. This is what urbanists would call the underbelly of the city, created partly by government policies of urban development in the rest of the city and partly by a steady influx of poor migrants. .

It forms a part of Mumbai North East Lok Sabha constituency which otherwise has a large middle to upper class spread comprising suburbs like Vikhroli known for its verdant trees and upper middle-class housing, Ghatkopar which is a commercial and resident hub for middle class to wealthy Gujaratis, and Mulund which has a fair count of modest to rich Maharashtrian and Gujarati families. The M-East part of the constituency does not quite fit in but it exists.

However, the enthusiasm here for the general election is hardly low. Local leaders of parties have taken over and do the ground work for the candidates of the national parties — Mihir Kotecha of the Bharatiya Janata Party and its allies Shiv Sena and Nationalist Congress Party who is facing off against Sanjay Dina Patil of the Congress, Shiv Sena (UBT) and NCP (Sharad Pawar). In the 2014 and 2019 general elections, the BJP took this seat but in two elections prior to them, the Congress and the NCP had won from here.

The sounds of an important election are back in these congested lanes and filthy bastis, the songs played aloud, flyers being distributed, election-related nukkad (corner) meetings being held and so on. Sabah Khan’s work is important because she reaches out to women on the importance of voting and what to keep in mind when they are in the voting booth.

But will people here vote, do they believe that their votes will make a difference?

Mixed reactions to voting

The M-East ward comprises migrant families, many of them new to the city but a few who have been here for generations without their lives improving, and a large number of project-affected persons (PAPs) evicted from their legal or semi-legal dwellings in the better-off parts of Mumbai to make space for infrastructure projects over the last 25 years.

In the Cheetah Camp area alone, live a total of 8,07,720[1] people of all religions, according to official data. Here, as the voting fervour picks up for the ballot on May 20, many are interested to get their finger inked but a few remain disinterested. There is an undercurrent of dissatisfaction with the current government and, given half a chance to be honest, most of them do not want it back in power. But they hesitate in saying so.

Many first-time voters like Aafreen Rabbani Mousa, 21, tailor, could not really care less about the world outside her home. She was satisfied that her father had registered her as a voter. “I do not have expectations in terms of education or employment. I have been watching YouTube videos of how to vote,” she says but fights shy of discussing her preferences or issues influencing her vote. Elsewhere in Cheetah Camp, on a late Sunday evening, women gathered at one of the masjids where they were informed about the importance of their vote as Muslim women and issues like the Asifa rape case, the CAA-NRC protests, and triple talaq.

School teachers and principals – all women – pitch in to help voters. Shabana Khan is among them. “When voters, especially Muslim women, find their names out of the voters’ list because they have shifted houses and so on, we help them with documents and also educate them on how to go about the enrolment process to ensure equal participation in voting,” she says.

Across Cheetah Camp, people’s demands are old, simple and basic — roti, kapda, makaan aur naukri (food, clothes, shelter, jobs). Their pathetic living conditions which have not improved for decades, they realise, are more to do with the local Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation than the Government of India but their chance at improving their lives in terms of jobs or livelihoods and household expenditure – including an LPG cylinder – have to do with the latter.

As in Cheetah Camp, so in the rest of the M-East ward – the narrative is of dissatisfaction, distrust, fear at being persecuted for their faith but quiet and invisible in their resistance – and voting.

M-East on no one’s radar

Given its large spread of Muslim and Dalit population with a sprinkling of OBCs and the preponderance of project-affected persons and migrants, slums or badly-constructed resettlement colonies are the most common form of housing here. In Cheetah Camp alone, nearly 78 percent of people[2] live in slums. The highest number of water supply complaints in Mumbai are registered in the M-East ward. Other grievances are about roads, drainage and solid waste management, according to a report by Praja, urban governance NGO.[3] [4]

The central government’s ‘Housing for All’ by 2022 and Swachh Bharat Mission on solid waste management and toilet construction across the country should have left the M-East ward in an improved state after a decade. Yet, in these lanes, there is hardly any talk of it. People have heard of these programmes but have not connected the dots between them and the abject state of their lives.

The squalor from M-East should have reached the BMC and government headquarters in Mumbai as well as in Delhi but it has not. Residents here hope that every election will bring them candidates who will at least hear them out, understand their issues, and move the needle two points ahead to improve their living conditions. This too has not happened. With cynicism riding high, their votes get aligned on the basis of caste and religion, their passions whipped up on the basis of caste and religion.

Added to the poor status, these factors have been powerful enough to bring out voters here. The overall voting percentage[5] in the 2017 BMC elections was 62.09 percent, higher than other constituencies that recorded between 48 to 58 percent. “Around 2,000 new voters have been registered this time in the Cheetah Camp,” says Sabah Khan, confident that people will vote in large numbers.

Issues persist, voters befuddled

Manohar Naidu, a corporator from Cheetah Camp area, says his ward lacks a proper hospital but political representatives have failed to address the lacunae.

“Rs15,000 crore has been spent on installing lights on the highway. That money could have been used to build a hospital here which is more urgent. The lack of doctors, proper blood banks and surgical equipment leads to delays in attending to emergency cases,” says Naidu. Even a basic amenity such as a market has been excluded from Mumbai’s Draft Development Plan 2034.[6]

With the Deonar landfill — Asia’s second largest open landfill which receives over 4,500 metric tonnes of garbage every day — only eight kilometres away, residents of Cheetah Camp battle against air pollution even on days when the rest of Mumbai breathes clean air. The M-East ward frequently records the highest levels of air pollution of the 24 wards in Mumbai. A power plant, petroleum refineries and the massive construction in the past few years have added to the pollution.[7]

The presence of a waste treatment facility, which also treats bio-medical waste, beside the Deonar landfill has added to the area’s pollution, say residents. According to RTI information, asthma led to 6,757 deaths[8] between 2016 and 2021 (except 2017 and 2020) here. Around five kilometres away, Govandi has seen the most number of cases of respiratory issues among residents even as the government-run Shatabdi Hospital lacks adequate resources and equipment to treat asthma-related emergencies.[9]

The oil refineries near Mahul contribute to the chemical waste and so does the incinerator which emits hazardous gas. Mahul was declared unfit for habitation during a case in the Bombay high court. “Pollution has been gradually affecting the health of everyone living and working in the ward but it has been largely ignored,” says housing activist Bilal Khan. The National Clean Air Programme, or even the BMC’s effort to use mist vans to keep down air pollution in select (better-off) areas have no presence here. “The process to avail schemes from the government is tedious for which locals require help from NGOs,” says Khan.

Asked about the Smart Cities Mission rollout, Naidu echoed residents: “Aap apne Taj Mahal ko savaro, dekho hamari halat, shaam ko yahan swimming pool ban jayega raaste mein,” (You all can decorate your ‘Taj Mahal’ but a ‘swimming pool’ of stagnant water will be formed here on the road by the evening). ‘Achhe Din’ is a slogan they have all heard but have not seen good – or better – days since 2014.

In Lallubhai Compound, Jitendra Bhagwan More, who works as a sweeper on contractual basis, wants this from any government – basic safety equipment such as headgear, gloves and a house. He fears that programmes like the Smart Cities Mission will bring in machines that could take away his job. “If I don’t work, who will bear my household expenses? I send my children to an English-medium school for a better future,” he says. Mehrunnisa, in her late 50s, is caustic about “waiting for ‘Achche din’”. A domestic worker who lives with her son and daughter-in-law, she lists problems from inflation to lack of job opportunities for women. “Voting the present government out is the only solution,” she says.

Rehabilitation

In these parts, women’s safety is still a matter of concern unlike many areas of Mumbai. With limited educational facilities, young girls are forced to commute long distances. “Many families get their daughters married off early or girls are forced to quit studies because of security reasons,” say Shabana and Bilal Khan, a housing activist. The number of dropouts from municipal schools here was 23.6 percent[10] in 2016. The M-East ward also had the highest number of malnourished children at 51 percent[11] in 2015-16 – higher than the city’s average.

Bilal Khan says the M-East ward needs to be rehabilitated: “The poor infrastructure of the ward is alarming, it slows down development given that the base isn’t strong enough to make sustainable changes.” However, the demand for better housing under various schemes was turned down by officials over the last few years who justify that it would be difficult to rehabilitate people from here elsewhere in Mumbai, he explains.

The legal-illegal conundrum hangs heavy here. At the dead-end of a lane in Cheetah Camp, a group of young boys standing over mounds of garbage point to an empty ground. There used to be a basti here but was demolished by the BMC terming it “illegal,” they say, which means voters have declined. The empty ground has been turned into a make-shift playground highlighting the lack of a safe open space for recreation.

Rehabilitation, as proposed by a BJP representative here, according to Naidu, means being “sent off to Mithagar in Palghar, Thane district” which will uproot them from their work and community support. “We will stay here. We just need facilities here,” he asserts.

The M-East ward in Mumbai could be as far away from a Smart City[12] as it could be – while the latter focuses on smart mobility, e-governance and e-services, stormwater management and so on, all that the M-East of Mumbai wants are basic civic amenities of safe and affordable houses, clean streets and sanitation, low air pollution, and work opportunities. Which candidates are listening?

Zoya Khan is a media graduate from St Xavier’s College, Kolkata, and recently finished the post- graduate diploma course at Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic, Mumbai. Khan, fascinated by people and their stories, is exploring filmmaking and screenwriting as a career.

Photos: Zoya Khan