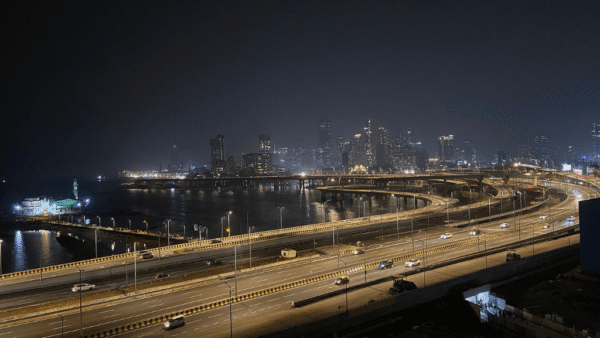

For children, a city is not just a network of roads and buildings—it’s a playground, a puzzle, and a storybook all at once. Unlike adults, who navigate spaces with routine and purpose, children engage with cities organically, turning a park bench into a bus, a narrow alley into a racetrack, and a flight of stairs into a castle turret. But modern cities rarely cater to this free exploration. Streets prioritise cars over pedestrians, playgrounds shrink into leftover spaces, and public areas become afterthoughts.

When cities fail children, they strip away the small joys that define childhood such as climbing a tree, chasing pigeons in the park, walking to school without fear. If children feel like outsiders in the places they call home, what kind of future are we building? It’s a question we must ask ourselves.

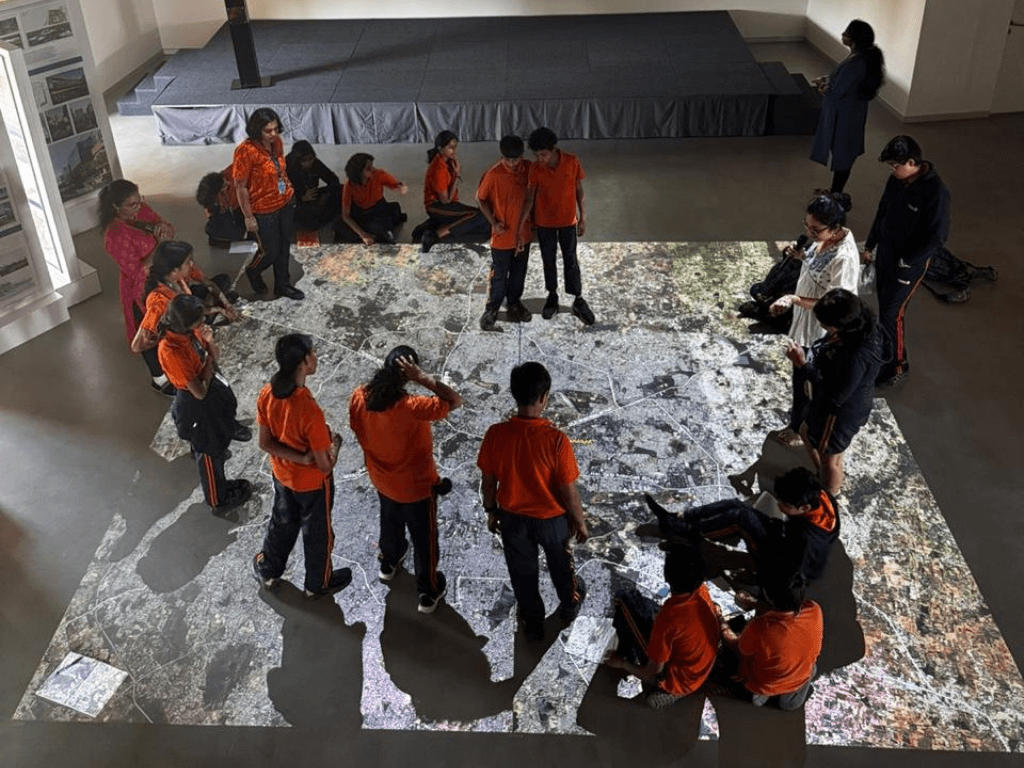

Cities are built for adults—commuters, workers, decision-makers. But children move through the same streets, play in the same parks (if they exist), and interact with urban spaces in ways that adults often overlook. Why aren’t they considered in city planning? This question took centre-stage during a session that we, at Mod Foundation, held and fondly called ‘Walk on Bangalore’. At BLR Design Centre, a dynamic space to engage with the city’s past, present and future, we engaged a group of young minds with the city in a way that left even us, seasoned architects and urban designers, in awe.

The aim was simple: Transform the city into a living classroom and enable participants of all ages to question, learn, and contribute to the urban discourse. We would be a bridge between citizens and subject matter experts, to foster a deeper understanding of the city’s layers. Their inquiries were not just expressions of curiosity but reflections of a deep, intuitive understanding of the city’s challenges.

Walk on Bangalore: Where it began

The original idea behind ‘Mapping Bengaluru’ which was version 1.0 of ‘Walk on Bangalore’—an ongoing research project at Mod Foundation—was to decode the city’s transformation through its historical maps and records. When ‘Walk on Bangalore’ was planned as part of the BLR Design Centre’s opening in November 2024, it was meant to be a fun, interactive way to showcase Bengaluru’s growth over time. A little nostalgia, a little history—simple enough.

Then came the happy accident, an unexpected surprise request. It was such a success that it sparked immediate interest, more requests to hold the session, conversations with curious participants, and an eagerness to share the experience with a wider audience. Swati Jain, a talented educator from Tapas Education, and a friend of Mod Foundation, casually asked if she could bring her students— 8- to 10-year-olds—to the session. She was ready to take a chance on this experiment. The Mod team hesitated, having never worked with little humans before. Should we simplify the content? Filter out the complexities?

Then came the realisation for us: Why dumb it down when children already see the city for what it is—chaotic, confusing, and often unfriendly? The decision was made. Content would stay the same, only the language would be simpler.

Photo : Namitha Nayak

A walk through time, literally

By viewing cities as living classrooms and playgrounds, children emphasised the need for inclusive, flexible, and nurturing urban environments. Their observations challenged conventional planning priorities, advocating for cities that are not only efficient but also joyful and engaging for all age groups. The session kicked off, and within minutes, doubts vanished. As the children stood on the massive map of Bengaluru from the 16th century, projected onto the floor, they were not just looking at history—they were stepping ‘into it’.

The team combined floor-mapping projectors showcasing Bengaluru’s growth over the centuries, using old archival maps as a guide. From the days of Kempe Gowda’s original fort to the modern sprawl of flyovers and tech parks, the maps told the story of a city in motion. A wall projector displayed archival images of markets, processions, and street life from different eras, creating a vivid visual timeline in tandem. A trivia session kept them engaged—”Guess which landmark this is?” or “Find a street that has changed the most over time.” Each question sparked a new set of observations, often leading to hilarious, yet insightful, remarks. “Wait, I have heard the name Majestic – we passed it on the metro ride.”

One child walked over the Kempe Gowda-era pette and immediately asked, “Wait, is there a chocolate pette?” Another participant, staring at a map showing encroachment over Bengaluru’s lakes, had a different concern: “If people build on lakes, where do the fish go?” The question struck a nerve—because what the child was really asking was what happens to nature when the city takes over. It is a question that adults should have paid closer attention to as they accelerated urban development.

The activity turned into an impromptu urban treasure hunt where they identified landmarks, traced old lakes that no longer exist, and even attempted to guess what areas of the city might have looked like before the buildings arrived. Another child pointed at an old lake on the map and asked, “If this was here before, where did all the water go?” It was not just an interactive history lesson; it was an exercise in critical thinking. The children were not just learning about their city—they were understanding it, questioning it, and reimagining it.

Photo: Mod Foundation

What children see that adults miss

Using some of their questions as examples, the team found themselves applying the complex theory of semantics (or at least attempting to) to interpret the wonderfully profound questions the children asked.

The question, “How can people build on lakes?” highlighted a fundamental urban issue—our encroachment on natural water bodies. Many cities struggle with flooding and water shortages precisely because of poor planning decisions. A child’s simple question cuts through layers of policy debates and exposes the core problem: We are destroying ecosystems for short-term gains.

“Do the pettes (markets) still sell the things they are named after?” was a reflection on Bengaluru’s evolving identity. Pette areas, historically known for specific trades, have undergone transformations that have erased their original purpose. This seemingly innocent question raised important concerns about heritage conservation, mixed-use planning, and the rapid commercialisation of historically important precincts or districts.

“Who should we go to with ideas about our city?” This question underscored a glaring, yet relevant, gap in public participation. Most city-making decisions happen behind closed doors, excluding not just children but also many older citizens. If children do not know where to take their concerns, it is a sign that participatory governance needs to be strengthened. The debate of whether lakes are more important or bus stations is one that even seasoned policy makers struggle with.

It brings to light the fundamental challenge of balancing ecological sustainability with urban expansion. In a child’s mind, the choice is not between one or the other; it’s about making sure both can co-exist. Maybe that’s a lesson the grown-ups should take to heart. Instead of viewing these as mutually exclusive, urban planning must integrate nature into infrastructure—such as green bus depots, permeable surfaces, and stormwater management in transport hubs.

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Little voices, big impact

Children experience cities at eye level—where footpaths should exist but don’t, where playgrounds have been turned into parking lots, where their everyday routes to school feel unsafe. And that’s the heart of the issue: Cities fail children not because they dislike them; they fail because they don’t think about children very often. If a city cannot offer a child a safe place to play, a shaded path to walk, or a simple way to understand its history, then what kind of future is it really building?

Schools teach about urban geography and history, a static truth, but rarely do they explore how students can actively engage with their surroundings or exert agency in shaping their cities. When children interact with their environment through movement, observation, and direct engagement, for example walking on a map, stepping over lakes and roads, and physically tracing urban growth, it makes spatial relationships tangible in a way no digital screen can replicate. They begin to see the city not just as a given, but as something that is constantly changing and hence something they can influence.

Exploring old images and maps helps children see how cities change over time due to social, cultural, and political influences. It shows them that cities are not fixed — they grow and evolve based on people’s actions and decisions. This helps children realise that they, too, can shape their surroundings in big and small ways. They begin to see that cities are not just places they live in, but environments they can question, contribute to, and transform.

Children are unencumbered by bureaucracy, politics, or financial interests. Their questions and observations stem from a place of genuine curiosity and concern. Cities are built to last decades, sometimes centuries. Planning with children in mind ensures that urban environments remain functional and enjoyable for future generations. By involving them today, we shape responsible citizens.

‘Walk on Bangalore’ may have started as an experiment, but by the end, one thing was clear: Our youngest citizens don’t just deserve a seat at the table, they might just be the smartest people in the room.

Photo: Van Leer Foundation

The way forward: Taking this beyond Bengaluru

If there’s one thing this serendipitous experiment at BLR Design Centre has proven, it is that children are brilliant urban critics—sharp, unfiltered, and full of the right questions. So, how do we turn this accidental discovery into something bigger and impactful, and in other cities too? Other cities have already shown that child-friendly urban interventions don’t need massive budgets. Rotterdam involves children in neighbourhood planning, making streets safer and more walkable. Bogotá transformed neglected streets with paint, pop-up playgrounds, and outdoor classrooms, proving that small changes can create vibrant, child-friendly spaces. Singapore installed interactive kiosks where kids can submit ideas for their neighbourhoods—because if they have concerns, why wait for adults to take them seriously?

In fact, the Mod Foundation team is now working to introduce ‘Walk on Bangalore’ as a module in the city’s schools with another friend of the organisation, Gully Tours. Anyone who is willing to break the mould could start. Bringing this to more Indian cities is simple. Start with interactive city walks. Let children trace history on large projected maps, ask their own questions, and rethink their surroundings. Use the city as a classroom. Schools can turn urban design into class projects, and local cafés, libraries, or bookstores could host monthly ‘City Labs for Kids’.

Why not let them redesign their own neighbourhoods, using anything from recycled materials to Lego blocks? The starting point is simple—open doors to young minds, and the results will follow. If we want our cities to be vibrant, fair, and sustainable, we need to design them with everyone in mind—including our youngest citizens. Because today’s kids are not just future city-makers. They are already shaping the conversation today. The least we can do is listen.

Cities aren’t just designed on computers—they are shaped by the people who move through them everyday. And if we truly want to build cities that are inclusive, vibrant, and sustainable, we must start listening to everyone, including and especially the children. Their questions cut through bureaucracy, exposing the gaps we often overlook. Their observations challenge our assumptions about what makes a city truly liveable. By giving them a voice in urban design and planning, we are not just creating better spaces for them; we are building a future that works for all of us.

Nidhi Bhatnagar is an architect and urban designer with a deep understanding of both theory and practice, and currently the team lead at Mod Foundation. Through her professional experience, she seamlessly bridges technical expertise with real-world application, working effectively with investors, developers, and operators in complex urban projects. Her design concepts are context-sensitive, and compelling, rooted in a keen grasp of the evolving urban ethos. Nidhi holds a Bachelor’s in Architecture from the School of Architecture, CEPT University, and a Master’s in Urban Design from the Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation, and Planning, Columbia University.

Cover photo: Children stand on a 16th century map of Bengaluru and look at the city’s growth. Credit: Mod Foundation