The geography of any city and its development is rarely understood and used from the point of view of open spaces. They are taken for granted and it is assumed that they will be consumed as the city is expanded, that they will be covered with construction in the name of development. But it is the state of open spaces that reflects the state and quality of life in a city, the dignity of public community and collective life.

Though open spaces are considered as recreation grounds, play grounds, parks and gardens in urban development plans, this is a limited view. The entirety of open spaces in a city should include its invaluable natural assets which are not usually seen as open spaces such as hills, forests, natural plantations, mangroves, wetlands, rivers, ponds, lakes, and in coastal cities, the natural coastline, creeks and beaches. Equally importantly, these should be mapped in a comprehensive manner and this priceless information should be made accessible and available to people if we are to see any change in the existing matrix of urban planning.

The marking and provision of open spaces are a part and parcel of development plans in cities because regulations make such a provision a precondition of urban development. However, the current paradigm of planning sees open spaces as constraints on development – taken to mean real estate and construction – or a byproduct of the real estate activity or left-over spaces. Open spaces are a lot more. Only when people are aware of the necessity and co-existence of open spaces in their neighbourhoods, in a proportion stipulated in most planning regulations and necessary for healthy, dignified and sustainable living reflecting the larger ecological attributes, can they fully participate in their planning and collectively decide the nature of growth and development.

It is also assumed, wrongly, that open spaces are nothing but open-to-sky spaces for people’s recreation and entertainment. This is but one function. Open spaces bring together a multitude of urban functions: ecological, social, public health, public safety, aesthetics besides recreation. The most iconic open spaces combine all or most of these functions. Planning requires public authorities to ensure that adequate, good quality and accessible spaces are available to all people as their right – and recognised as part of the fundamental Right of Life encompassed in Article 21 of the Constitution. But the need of the hour is to recognise natural areas as open spaces and integrate them so that the definition is expanded. This will help raise public consciousness about open spaces and initiate better city planning.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Open spaces and planning

Besides the recreational opportunities they provide, open spaces are significant from the standpoint of public health. Medical experts have advocated for decades that such spaces are essential for physical and mental well-being.[1] After all, the origins of urban planning in Indian cities date back to the devastating epidemic outbreaks during the colonial regime and regulations which followed to ensure adequate open spaces for light and ventilation as preventive measures.

Open spaces are also important from a safety perspective. During emergencies such as fire outbreaks, earthquakes and other disasters, they serve as refuge areas for people. It follows, therefore, that there should be sufficient open spaces in every neighbourhood – not on podiums in gated complexes and private areas, but at the ground level of the mother earth which are networked across neighbourhoods, and are accessible to one and all.

The networking of open spaces in a neighbourhood and across a city is more important than acknowledged in planning. This gives us the powerful idea of linear parks – kilometres of green open spaces which are interlinked across a city – akin to a river flowing and connecting millions of people. This is important to address the segregation and fragmentation that happens in cities, and also to challenge the idea of centralisation with one large park for the entire city. Linear parks make open spaces more accessible and democratic to more people.

Open spaces are equally important for a city’s ecology too. This function has been largely ignored but they offer a range of ecosystem services. Groundwater percolation is one of them. By absorbing rainwater into the ground, open spaces help reduce the surface runoff in our built environment and the intensity of urban flooding. Unfettered open spaces at the ground level, on mother earth as it were, can reduce the impact of the urban heat island effect and regulate the microclimate even in highly dense neighbourhoods.[2]

Open spaces also support natural vegetation and, therefore, carbon sequestration which is now an important means of climate change mitigation. And open spaces help to improve the air quality by dispersing polluted air, and support biodiversity which is critical to maintaining the natural ecosystem in an urban environment. Open spaces are the best home to trees and urban forests without which cities remain an unbearable mass of concrete.[3]

It is, therefore, imperative that open spaces are duly recognised in the planning process. Let us imagine a network of open spaces in a city being at the heart of urban planning and development. This is contrary to the prevailing notion about open spaces as wasted spaces to be used to maximise the construction and real-estate potential. We badly need this shift in planning.

Our Mumbai mapping

Networking various open spaces in a city into linear parks allows the development of an elaborate system of green connectors amidst the concrete. These can be avenues, gardens, promenades, boardwalks, cultural squares, wetlands, salt pans, beaches, promenades, and rock formations. Both the natural and built open spaces can radically enhance the character and quality of the city’s landscape. Such a network will not only improve the environmental condition of the city but also provide opportunities to millions of people for walking, cycling and, importantly, social networking which help bring people together in an urban environment known for atomising and individualising people.

Photo credit: Mumbai’s Open Spaces

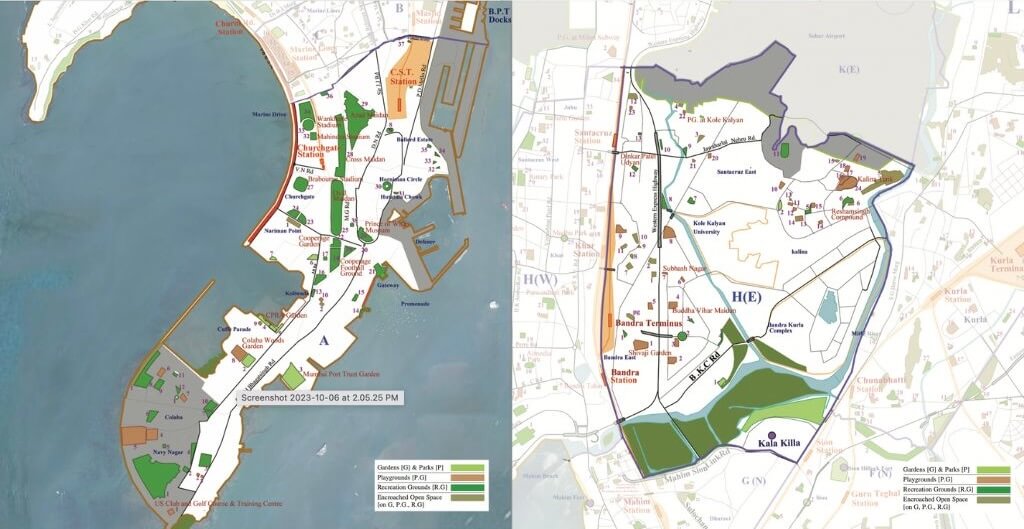

This is especially significant in a dense city like Mumbai where the availability of open spaces is well below the internationally recommended level. Mumbai’s development plans classify open spaces into recreation grounds (RG), playgrounds (PG), parks (P) and gardens (G) overlooking the many natural open spaces available in the coastal city. However, even within the limited definition, there is an important lapse: it shockingly lists far fewer open spaces than there are.

Mumbai’s Development Plan 2014 listed 800 reserved open spaces across the four categories of RG, PG, G & P but in the comprehensive survey and mapping that some of us undertook in 2011, we found a total of 2,152 reserved open spaces in the above categories – nearly three times more. This was presented to the city as Mumbai’s Open Spaces Map[4] and a preliminary listing document which, I believe, was a necessary step towards a comprehensive plan.

Of the 2,152 reserved open spaces, nearly 600 spaces were encroached upon and, in many cases, built upon too. Comprehensive information of 752 spaces was not available with the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) which is solely responsible for the city’s open spaces. A check with a few of the 24 ward offices across Mumbai confirmed that there was neither a thorough documentation of open spaces within a ward nor consolidated information available to people. Moreover, natural spaces were not classified as such but simply marked as No Development Zones which means they could be released for development later. Our mapping suggested classified reservations in the NDZs.

Unfortunately, the DP 2034 did not improve on this. This abysmal situation warrants people’s intervention where we have to join hands to prepare a complete inventory of open spaces in our neighbourhoods. This information can be made widely available so that any move by the BMC to change the classification or nature of an open space can be effectively and locally resisted. This would also help to democratise the process of planning, implementation, and monitoring. It is our collective responsibility to ensure that all open spaces are protected from abuse and misuse – and remain open to all.

However, this does not mean that the BMC is off the hook. It is the civic body’s responsibility to prepare a comprehensive record of all the reserved open spaces irrespective of their ownership. If some are privately owned, the BMC must initiate the acquisition process with utmost priority in a time-bound manner. Under no circumstances should construction be permitted on these spaces; the relevant laws and Development Control Regulations must be amended to prevent such construction. It is the BMC’s responsibility and duty to prepare a comprehensive map of open spaces and maintain all such spaces in collaboration with people. This map should be available to all.

Mapping, open data, and protection

The ward-wise Open Spaces Map and the detailed listing of open spaces in each of the 24 wards across Mumbai which we carried out was not an end in itself. The mapping and listing were to re-envision Mumbai’s plan in an ecological way.

The mapping included all the RG, PG, parks, gardens, natural and ecological assets such as hills, forests, water bodies and so on, public places such as railway stations, markets, and public amenity buildings too. This was the first such map in Mumbai and it showed a distinct geographic character of the city. The Open Spaces Map also marked out encroachments. Of the 2,152 open spaces tabulated, at least 1,552 were available while nearly 600 were encroached upon. The DP 2034 ought to have acknowledged this, incorporated a similar tabulation as part of the official document, and ensured that the open spaces are protected from all building activity irrespective of the purpose of the construction.

Despite the comprehensive Open Spaces Map and ward-wise tabulation made available for the first time, the BMC and its outsourced planners overlooked the city’s open spaces network. The information could have been used to facilitate meaningful public participation and dialogues during the preparation of the DP 2034. This was not done. What will happen to the open spaces we had tabulated in every ward by 2034 is anyone’s guess.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What lies ahead

The monitoring of the thousands of open spaces across Mumbai is necessary now especially as the new regulations allow for construction without even providing open spaces on the ground. In essence, the regulations allow builders to construct on every inch of a plot and provide ‘open space’ on the podium of a gated complex. This is scandalous.

This has been challenged by me and others in the Supreme Court on the basis that the podium-level open spaces cannot compensate for their absence on mother earth. They are an apology for open spaces and perform none of the vital ecological functions that natural open spaces do – they cannot absorb rain water to reduce the runoff and increase the groundwater level, they cannot support trees which are essential for carbon sequestration and micro-cooling of areas, and they cannot help in mitigating climate change impacts.

This assault on open spaces is at odds with what the Mumbai Climate Action Plan stated about open green spaces and trees: “The city will work towards green space access for all citizens, undertake conservation and extend biodiversity to protect the city from the impacts of climate change. Urban green cover helps minimise the mean rising temperature, reduce the effect of heat waves, and arrest urban flooding. This goal can be achieved by increasing the vegetation cover and permeable surface of the city surface area by 30-40 percent by the year 2030 and reducing the heat island effect…Ensuring an equitable distribution of open spaces, increasing the per capita open space to 6 square metres by 2040 and restoring, maintaining and enhancing the city’s biodiversity and ecosystem will also be important”.[5]

The loss of open spaces on the ground level and consequent depletion in tree cover is likely to have devastating impact on flooding during intense rain events which studies have indicated a rise in the coming decades, depletion of groundwater table which could lead to soil changes, loss of natural ecology and biodiversity, rise in overall ambient temperature, and an exponential increase in building density in an already super-dense city.[6] Without natural open spaces on the ground, Mumbai risks becoming a hotter city; studies show that open spaces with concrete paving were 1.5 to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than surfaces with trees.[7] Urban forests and lush tree covers cannot be replicated at podium level. Plants in pots at podium level placed around manicured green lawns are not a substitute for trees at the ground level in terms of environment and climate change threats.[8]

People’s participation can ensure that open spaces are protected. Within neighbourhoods, people can add to our documentation, fill gaps if any, organise exhibitions and dialogues at the open spaces, and evolve ways to maintain and protect them. Various citizens’ forums, residents’ associations, and other groups are welcome to use the Open Spaces Map and ward-wise listing we created.

Eventually, we can hope that such participatory activities will augment our list and people’s movements will help evolve plans in each of the 24 wards in Mumbai so that the city’s meagre open spaces, its ecology, can be preserved especially from the brutal construction onslaught.

PK Das is an urban planner, architect and activist with more than four decades of experience. He has been working to establish a close relationship between his discipline, urban ecology and people through a participatory planning process. He has received numerous awards including international ones for his work in revitalising open spaces in Mumbai, rehabilitating slums and initiating participatory planning. He is also the founder of Question of Cities.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey