The gentle January sea breeze blowing across its 225 acres makes it the perfect time to be at Mumbai’s Mahalaxmi Racecourse. There’s unobstructed bright blue sky beyond its expanse, a skyline of rising towers around its eastern edges, a host of birds make a chorus of sounds above, ancient trees stand tall around its perimeter, the air smells clean and fresh as horse riders, walkers, joggers, football players and yoga practitioners take it all in. This is a rare space in Mumbai, by any standards.

Reclaimed from marshy land that was previously called the Mahalakshmi Flats, the Racecourse, housing the Royal Western India Turf Club (RWITC), occupies prime sea-facing real estate that is eyed by many. The land was leased from the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) to the Mahalaxmi Racecourse in 1914; it finally expired in May 2013. The past ten years have seen renewals of the lease as well as attempts to make ‘productive’ use of the prime land.

The latest salvo from the BMC is the proposal to construct a theme park spread across 120 acres of the land leaving about 90 acres for the Turf Club and its activities. The theme park, now controversial and challenged in the Bombay high court, will mean that one of Mumbai’s largest open spaces will no longer remain vacant, uncluttered, and accessible to all. In a city starved of open spaces, this is more significant than authorities care to acknowledge.

The Racecourse is seen as an elite space but only the Turf Club and its premises used as horse stables and offices are out of bounds for people without membership of the club. Large parts of the Racecourse attract a number of Mumbaikars from the crack of dawn to late evenings, providing a whiff of fresh air in the concrete jungle. The Turf Club has a social ecology of its own. The site was accorded Grade II-B heritage status which means it is largely protected and implies a precinct of local importance where construction is avoided.

At the heart of the controversy over the redevelopment of the Racecourse, into a theme park or whatever else, is not merely the control over this public open space but the purpose behind it. The BMC is the guardian of this open space; it has been functioning as a developer-broker.The people of Mumbai have the greatest stake over this expanse. Their say matters, or should matter, but the BMC’s actions hardly reflect this.

1. The BMC’s proposed park plan. 2. Red dashed line indicated the boundaries of this plot as per the MCGM of G/S ward plan. 3. The roughly 90 acres of land that are currently accessible for people to use for recreational purposes.

Why the open space matters

The 225-acre land of the Mahalaxmi Racecourse is shaped like a boot (perhaps, a Christmas stocking) tucked between two arterial roads, the E Moses Road to its east and Lala Lajpat Rai Marg to its west. The almost-oval racecourse forms the lower part while the northern part, a trapezoid, comprises the stables and auxiliary amenities of the Turf Club. To the south of the racetrack are the functional buildings of the club, its grandstands, and a spattering of restaurants. The walking track and central area, roughly 90 acres in the centre, are publicly accessible and used areas.

A major chunk of land that the BMC proposes to use for the theme park is this open and spacious central portion of the track, half of which is currently used for the Amateur Riders Club and the polo field while the other half is leased for commercial and private events. These spaces are usually open to the public – teenagers play football on the expansive field where polo tournaments are held, Mumbai’s ubiquitous cricket matches can be seen, people do group activities like yoga, and a stage prepared for a globally recognised music festival. The Racecourse, for those who know and use, remains an important public open space within the timings set by the Turf Club, which leads many Mumbaikars to believe this is private club land; the BMC does little to correct the impression. The Turf Club faces a host of challenges including reduced footfall at races and higher taxes on betting. However, these are of no bearing on the public land and the civic body’s plans for it.

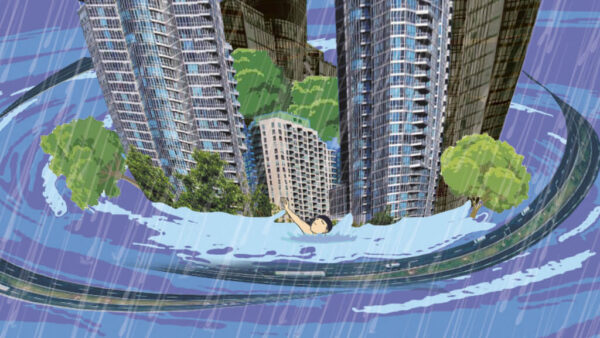

The Racecourse land is one of the largest open spaces in the city, a relief from the concrete jungle, clearly seen in a satellite image. The few large open spaces in Mumbai are inequitably located. Most of them are in the south to the centre of the city – the old city, as it were – while its expanded suburban areas have few, if you discount the Aarey forest. This means Mumbaikars travel long distances to make use of the Racecourse space. A theme park would hardly offer the expanse that this open space does.

However, the theme park is not the first proposal for the space. There have been several, from the pragmatic to the inane, over the past century. In 1948, planners NV Modak and Albert Mayer, as part of the master plan for the city, wanted to relocate the Turf Club’s activities and use the space for low to middle-income housing in between public parks. They stated: “In Bombay’s lack of parks and playgrounds there is probably no sizeable city in the world to compare it to.” In 2009, authorities planned a bridge over the Racecourse to alleviate the congestion of traffic headed towards south Mumbai. The theme park proposal was mooted first in 2013 and has been revived now.

While the contours of the theme park are not yet clear, what is certain is that it will dramatically change the way the space is now and how it is cherished by thousands. The park, which may be ticketed to cover costs, will mean construction cutting into the open space and possibly an end to the free access that people have, making this large open space a collective memory of the city. BMC Commissioner IS Chahal has assured the Turf Club members that a theme park will not necessarily mean an entertainment park with construction but there are proposals to erect a London Eye-like structure and construct an underground road 8feet below to reach the gardens of the new Coastal Road and so on. [1] [2] [3]What is needed is an open public discussion of these proposals.

Its ecological functions

The various ecological ramifications are less discussed. Mumbai has been grappling with increasingly poor air quality[4] with a 38 percent increase in PM2.5 levels from 2019 to 2023.[5] Bad air, as is well established by now, is directly related to and is the cause of a number of health problems. The correlation between air quality and urban land use, including the availability of open spaces, shows that they help to reduce the pollutants in the air and bring down the Air Quality Index.[6]

The relatively low-lying location of the Racecourse allows space for the rainwater to collect every monsoon which perhaps motivated old-time planners to consider turning it into a reservoir. Concretising vast stretches of the Racecourse, extensive piling and deep basement work[7] required for a theme park would prevent water from percolating into the earth, adversely impacting aquifer recharge and the groundwater table.

The trees, some over 100 years old, are a majestic canopy, offering respite from heat. They are critical to mitigate the Urban Heat Island[8] effect in which certain areas are hotter than their surroundings due to a combination of low tree cover, heavy concretisation, use of heat-trapping building materials, and traffic emissions. Those who use the Racecourse affirm this. While training for the marathon, Kushal Borlikar felt the area was cooler: “It was one of the advantages of practising here, especially during summer. Even a couple of degrees cooler makes a lot of difference.”

This open space is critical in a city with 1.24 square metres per person which is projected to reduce to 0.87 square metres per person.[9] The central government guidelines recommend 10 to 12 square metres.[10] Delhi is way ahead of Mumbai; south Delhi offers nearly 43 square metres per person while northeast Delhi has the lowest at 3.22 square metres which is nearly three times Mumbai’s average. This average, as per the BMC, includes traffic islands and rocks along the seashore too.[11] Ironically, Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 promises 2 square metres per person.

The people of the racecourse

Over the decades, people have claimed and used the vast expanse independent of its function as a racecourse. Universities and colleges hold their track-and-field trials for state-level competition, bringing in hundreds of students for practice, some as far as from Virar nearly 75 kilometres away.

Aspirants to the police force and railway jobs like Nikhil Thakur train here too. “There is no space on the roads. We have grown up in this area and come here since we were children. There are many other groups for running, yoga and more who come too…If a theme park comes up here, the walking track will cease to exist,” says Thakur.

Kushal Borlikar, training for the marathon, says: “Training on the road is no easy feat even early mornings. Here, there are no traffic signals, we do not have to watch out for cars or damaged roads, which allows for speed training. This place also offers the thrill sometimes of horses running on the track next to us.” RPF jawan Rajendra Yadav was training for the city’s annual half marathon and said “there is no alternative” to this space for training.

People living in railway quarters nearby come here for leisure or for sports practice. Teenage members of the Amateur Riders Club make videos of the space. “Everyone is welcome here, we want the place to remain this way and are looking for people to interview for our film,” they say.

Quite a few people come here in the mornings and evenings to play cricket and football, or walk and exercise, while others come to watch the horses run. Football coach Suraj Jaiswal has been coming here for 20 years though football was only permitted five-six years ago. He says, “We really don’t need anything else here. If this place goes, it will not be economically feasible for my students or me.”

Over the years, people have been involved in keeping this open space accessible to all. In 1986, when the club restricted access to people, Nivedita Shirodkar recalls standing in protest with a large group outside the Lala Lajpat Rai Marg gate. “Within a couple of days, the gates were opened to us,” she says. Purusottam Singhi narrates the involvement of the Joggers and Walkers Society (JAWS) in the use of this space. Both of them, former presidents of the society established in 1983, state that the absence of a clear public access to the walking/jogging track in the theme park proposal makes them wary; the walking community here would echo this. Instead of restricting people’s access, the authorities must take steps to make it more accessible.

The future

The boundaries of this open space have been blurring. The Arabian sea, Haji Ali Dargah and Mahalaxmi temple could be seen from its western gate till recently – views now blocked by the under-construction coastal road. The north-most part of the land was given to the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority for Line 3 of the under-construction metro. The avenue of magnificent trees to the south has been shrunk for road widening and a flyover. The construction of a cycling track, enclosed by tall fences, is underway. Tender notices have been issued for a promenade development on the Lala Lajpat Rai Marg side to the Mahalaxmi bridge.

With the edges of the open space thus threatened, a theme park means the land inside is threatened too. Irrespective of the fate of the Racecourse, will the Open Space Policy being drafted by the BMC apply here? A state government minister recently stated that the coastal road[12] could be connected to the park by a tunnel. Have feasibility studies been done for this or any other proposal? The BMC Commissioner stated that the theme park will be eight feet lower than the race track, implying concretisation and shore piling. A prominent Mumbai architect has suggested, in his capacity as consultant to the BMC, that topiary gardens like at the Palace of Versailles should be on this land.

Do Mumbaikars really want this development? It is simple to find out, says Pankaj Joshi, Principal Director, Urban Centre Mumbai, suggesting surveys and crowd-sourced ideas. “Such an important decision should be taken in a democratic manner…Multiple proposals must be invited, published and city-wide consultation campaigns run for opening a dialogue with the public to democratise decision-making.”

Robert Stephens, Founder of Urbs Indis and author of Bombay Imagined, points to proposals in 1865 and 1948. Former municipal commissioner Arthur Crawford imagined a 400-acre park to detoxify the Mahalakshmi Flats, Bombay’s first landfill; J F Bulsara proposed an expansive campus of the Bombay University, and the Modak-Mayer outline building low and middle-income housing. “All three were incredibly forward-thinking dreams which understood that this land would have an impact across the city and all sections of society,” says Stephens.

The ideal would be to simply leave the vast open space the way it is and undertake minimum upgrades in an ecologically-sensitive manner. The storm water drainage could be improved. Storing and harnessing rainwater can provide ample water for the racecourse reducing the current reliance on water tankers. Improving the public ground so that people can better access the space throughout the year may bring more Mumbaikars here. Subtle zoning and landscape design, well-designed and adequately-lit footpaths can elevate the open space into a frequently-used, luscious green ground.

As the future of this iconic open space of Mumbai hangs in balance, it is worthwhile to remember that open spaces were created to counter an old pandemic. Wrote J F Bulsara, in “Bombay, a City in the Making” in 1948: “…Our concern is not with a bigger Bombay but a better Bombay. A city is not great by its size, area or population, nor by its piles of buildings and sky-scrapers. We are not even laying down our objective of an ideal city as a great city, but as a good and beautiful city; a city that invites and enthuses the joy and fullness of life here and now, not one that demands the monotony of drudgery…” The imagination of open spaces, if anything, should have improved since.

Trisha Salvi is trained as an architect and has worked in myriad roles in art, design and urbanism, in Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Chandigarh. She sustains her passion for cities by photo-documenting them, speaking to strangers on trains, and walking around them till she has a suntan and blisters on her feet.

Photos: Trisha Salvi