Food is an integral part of celebrations like festivals, weddings, birthdays, or funerals and protests, even the subject of music and art. The two women featured in this interview have gone way beyond recipes, even heirloom recipes, to think and reflect upon food trends, changing palates and more. With culinary chronicler and food consultant Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal, who shuttles between Mumbai and Dehradun, and Bengaluru-based independent food journalist and author Ruth Dsouza Prabhu, Question of Cities explores a veritable platter of festival foods, memories, trends, and more.

Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal, owns and manages a culinary consulting company, A Perfect Bite Consulting, which does research, culinary chronicling and food trends. She is also the curating editor of the annual Godrej Food Trends report – a qualitative and quantitative deep-dive into the food industry. A Gujarati who grew up in Mumbai and married into a Dehradun-based family, she is now into researching-chronicling and teaching foods of these traditions besides others, and independently publishing journals and books.

What are the food memories you have carried with you?

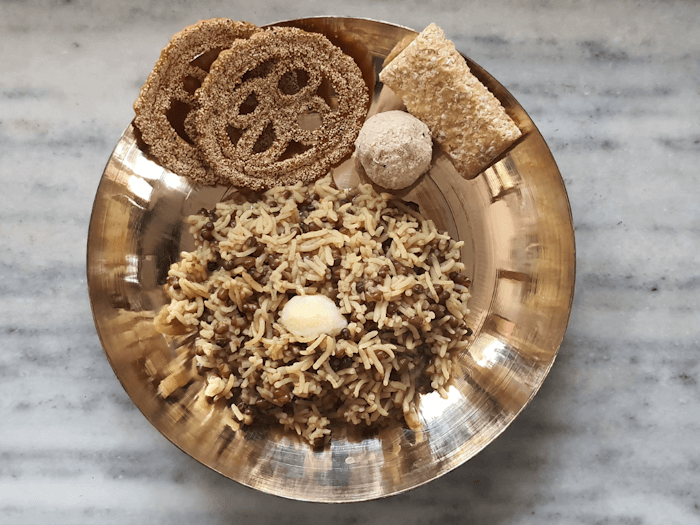

I am very lucky to have grown up in a Gujarati family in Maharashtra and marry into a family in Uttarakhand. I have seen different cultures with a lot in common. One of my fondest memories is of Sankrant. In Maharashtra, tilgul is associated with the festival. In the days running up to the festival, we had so much fun – my older cousins prepared the kites and manja days in advance, we would sit listening to their gossip and help them if we were allowed to. Til (sesame) laddoos and chikkis were prepared, so we would keep snacking on them as we passed by the kitchen. On Sankrant day, we would be on the terrace almost all day. A full meal was not cooked, fada ni khichdi and fada no sheera along with snacks like dhokla were the focus of this festive meal. After I got married, I learned that Sankrant is celebrated in a different way in Uttarakhand. Tilgul is common but in different forms. The North has gajak along with til ladoo and urad ki khichdi. We now celebrate in both ways while also trying different things. Across India, wherever the festival is celebrated, I see some form of khichdi and some preparation of til.

What changes has the commercialisation of festival foods brought about?

As somebody who lived in Mumbai in a joint family, the tradition of Diwali faral started a month in advance, especially when my dadi was around. It would include making gathiya, chorafali, and other snacks well in advance. On Diwali day, there was a puja and, on New Year Day, all the snacks would be spread out on a round table in our drawing room. Back then, families were large and houses were big, so everyone came together in festive spirit.

In the nuclear family with my husband and kids, our different schedules meant that Diwali preparations began only a day earlier. I found it convenient to outsource things and would order special mithai or faral from home chefs. It was great because I got traditional home-made dishes but saved time. There is, of course, commercialisation of food in cities but it does not wipe out traditions. People in cities don’t cook much at home during Diwali. There’s a lot of outsourcing because there are great options available for food gifting, everything from traditional faral to Diwali-themed chocolates and cupcakes, and something for every budget. In Mumbai, I also got to order different kinds of regional offerings like chhena poda for Diwali one year and baklava in tilgul flavour for Sankrant another year.

Living in Uttarakhand now, I find that away from urban centres, things are less frantic during festivals. All the elements and foods are very much there but it’s simpler, more leisurely. In Dehradun, during Diwali, we light about 50 diyas in mustard oil around the house, and there’s also a little nip in the air which makes it special. Diwali morning starts with keel or puffed rice and patasha or sugar candy eaten with milk. For kids we have something called khilonas which is sugar shaped in different moulds. My husband has fond memories of khilonas. You crush patasha and mix it with keel and milk, and that’s your breakfast. My favourite dish is the upma that’s made two-three days later from the leftover keel.

Photo: Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal

What items have gone out of the plate in festival celebrations in cities?

The biggest factor is convenience. If something is not convenient, it falls out of practice. That said, there are also people who realise that some traditional things we did were good for us like making pickles during summer and jams from fruits in winter. In Dehradun, we make it a point to get together as soon as the shraadh period ends, by which time the monsoon is also over, to make something called naal badi out of colocasia stems. It’s skill-intensive and time-consuming, but the ritual has passed down in the family. When you move away from traditional homes, you also move out of traditional systems where there are more people to do things. In between work and home responsibilities in nuclear families, things get left behind. It takes time and motivation to prepare a traditional meal or cook elaborately for festivals.

In my chronicling, I have realised that our festival traditions are aligned to when we did not have watches or calendars to mark time. Festivals were the markers of the change of seasons; the timeline of festivals and seasons showed us how to eat. For example, Sankrant is when winter foods come in. Odisha’s Pakhala made from rice fermented overnight, known in other regions as Phantabhat, tells us that spring equinox is over and summer is about to start, so cooling foods come in.

The prasad given during festivals was when vaccines or medicines did not exist as they do today. Many kinds of prasads like Panchamrit were made to boost immunity and prasad changed according to seasons. Mithais are basically high-energy foods but not in the same way – kheer in summers is cooling while halwa has ghee and flours which together warms your body in winter. My hypothesis is that ladoos have origins in Ayurveda; certain ingredients were crushed and sugar-ghee added before shaping it into small balls. Every occasion has a specific ladoo. In many homes, you see grandmothers still make ladoos on certain days or for kids who are travelling away from home. It’s a way of showing love but there’s also a nutritional aspect. These were high-energy foods made with health-boosting ingredients And it’s a tradition. My nani would send for us, now my mother sends for my children.

Photo: Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal

What drives you to document food traditions and dishes?

The more I study about Indian food and culinary traditions, the more I am in awe of how our ancestors had figured out so much. What’s on our Indian plates is for taste and flavour, but also has roots in Ayurveda and seasonal eating. It takes into account the relationship of the human body to the environment. While we may have inherited how to do it, we have not learned why we do it. A simple example is tadka. It adds flavour to dal or sabzis but it’s also important for plant-based diets because these nutrients are oil soluble; the fat of the tadka helps us absorb them better.

Similarly, in turmeric milk, the fat in the milk helps our bodies absorb the benefits of turmeric or curcumin. I know all this through research because no one ever tells us the ‘why’. Today, we make dal-bhaat but in a routine manner but if you look beyond, not only does dal change as we travel across the country but every dal has a different tadka based on seasons. In monsoons, a few cloves may go into some preparation while summer dals are lighter in spices. Indian cooks have such traditional permutations and combinations that they calibrate and apply to daily cooking based on the climate, season, and the health of people at home. If someone has a stomach upset, there’s more asafoetida in the tadka; if someone has a cold, there’s extra ginger. This is inherited knowledge.

The idea of archiving is to keep such knowledge alive and in practice, beyond recipes in a cookbook. Documentation is important. And modern science is ratifying traditional practices. Haldi Doodh, now popular as turmeric latte, is a great example. There’s a ‘new’ concept called meal sequencing, in which one eats raw vegetables before the main meal but in traditional Bengali or Maharashtrian meals, this was always done as koshambiris or salads. Then, there is intermittent or circadian diet but, historically, according to documentation available, people ate this way before we got the colonial breakfast-lunch-dinner. So, modern concepts like circadian rhythm eating, root-to-tail eating, zero-waste cooking are traditional practices. Traditions survive centuries because they work; documentation helps understand them.

Ruth Dsouza Prabhu is the go-to food expert for all things Mangalorean Catholic in the culinary sphere. A popular food journalist and author, she co-authored and edited India’s Most Legendary Restaurants based on the Taste Atlas, and is a contributing author to The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine in which she plumbed the depths of her hometown Mangalore.

Would you talk about your journey with food writing over the years?

I have been a food writer for the past 17 to 18 years. Although I started out doing food journalism with listicles and trend articles that publications wanted, I have lately focused more on food histories, traditions, and cultures. On my social media handles, I try to talk about Mangalorean Catholic culinary traditions which are native to me because a lot of the old traditions and history are disappearing. It’s my attempt to keep them alive through a medium that’s popular today.

What are the memories of festival foods you have carried with you?

Catholics don’t have too many festivals but, in whatever we do, like in any Indian tradition, food plays a huge part. From my childhood, I remember the feast of Saint Mary, called Monthi Saibinichi Fest in Konkani, which falls on September 8 every year. It’s a harvest festival, we make an odd number of vegetable dishes along with other delicacies, and the entire family comes together. Even when I was away for college and work, I would try to come home for it. The feast was always in my mother’s house; it’s tradition we continue even today.

Of course, Christmas is the biggest festival for us. There’s the western food which naturally came into Christianity but Mangalorean Catholics celebrate it slightly differently. One of the things we have is a collection of different sweets called Kuswar which used to be made only at home but are now outsourced or commercialised. Our chicken roast is also Indianised, our biryanis are different. You will find these flavours in the Anglo-Indian community in Bengaluru.

I married into a Gaud Saraswat Brahmin family and my husband is from Kochi. As an interfaith couple, we wanted to bring up our child with an understanding of different food cultures including the ones in Bengaluru where we live. So, we make it a point to celebrate key festivals such as Easter, Ganesh Chaturthi, Onam, St Mary’s Feast, Christmas, and Eid, and learn a little more about them. Every year, I try to change the themes a bit. I have been cooking Onam Sadhya for ten years now but realised last year that different regions of Kerala have variations of the same dish. I wrote about it and brought it into our Sadhya. The Thalassery side, the Syrian Catholic side and the Malabar side were represented this year; we had 22 people over for the meal.

Photo: Ruth DSouza Prabhu

How significant has been the practice of feasts or eating together during celebrations?

Food has always been a brilliant way to connect with people because all of us have to eat. In school, if children sit together with their dabbas, and someone’s dabba will have biryani on Eid or a mother would have packed an extra dabba of biryani, which helps them appreciate other cultures. We seem to have lost sight of it now but this is how our country stayed together. Food has a strong ability to unite people, to exchange an understanding of each other’s culture, and teach us to live in harmony. But it can also be a massive dividing factor – religious perspectives or meat-versus-vegetarian choices. Anything can become a flashpoint but food has immense responsibility to bring people together.

What changes do you see with the commercialisation of festival food like faral?

When all festival food was made at home, women could not step out to do anything else but society has changed a lot. That we can continue to revel in food traditions without putting the entire burden on women is great. Women have also turned it into their work. I get my Kuswar from a specific woman in Mangalore because it matches the taste in my memories. The flipside of commercialisation is the loss of bonding that happens when people sit together and make something. Like the ladoos during Diwali was, in many homes, a family activity. Knowledge about food and its traditions got passed down this way, which is now lost. Also, only certain food items lend themselves to being commercialised; not all. So, a lot of knowledge and traditions around festival foods are dying.

What foods have gone out of the plate in celebrations in cities?

Many labour-intensive traditional sweets like mani (pudding) have. It has to be stirred for hours before it comes together and then set. We now have a shortcut method using ragi which sets easily; the original recipe that uses raw rice and palm sago starch stirred together has gone off the scene. A celebration food we make is called Leitao which is an entire pigling roasted in an open pit usually on Christmas or a wedding; there is literally no one doing this anymore. Someone who is old-school might cater it for you but it’s rare. The last time I saw it was at my wedding, 21 years ago. Most of our sweets are still made traditionally. My mother definitely knows different payasam preparations that are not around anymore.

Photo: Ruth DSouza Prabhu

Why do you archive and document dishes?

My mother wrote about Mangalorean Catholic recipes called Randhaap Shindhaap first in Konkani and then Jane Dsouza’s Cookbook in English. I wanted to modernise traditional cooking, make it more accessible. There are things she tells me from her memories of her mother cooking and it does not remain a simple recipe in the book. I wanted to document it all – the memories as well as the food. I also find that it’s an interesting way to connect with people. The lineage of Mangalorean Catholics is supposed to have started from River Saraswati, across Bihar, then to Konkan, Goa and, after the Portuguese inquisition, down to Mangalore and Kerala. There are a lot of crossovers between Saraswat Brahmins and Mangalorean Catholics in food, versions of the same dish. We have a dish called pathrade with colocasia leaves. I believe there’s a version in Bihar and I’ve had another version in Arunachal Pradesh. One dish but three communities talking about it. I am excited to connect the dots in history.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, works with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover photo: Aishwarya Dhamapurkar