The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its sixth assessment report has warned of more intense storms and flooding as the planet warms. This is not the first warning bell. Even as dire predictions about rain and submergence turn into reality, cities across India have hardly taken concrete steps to address flooding. Instead, trees are razed for infrastructure projects and high-rises, water bodies are built over or lie neglected. How are city planners still designing urban spaces without understanding the consequences?

Most cities in India have the same story — expanding built areas, rapid depletion of vegetation, and more flood-prone areas. Though ‘resilience’ has become a buzzword, the efforts to make cities flood-resilient are half-hearted at best. For the past few years, there have been talks to make Kochi, Mumbai, and Chennai sponge cities – cities, which absorb rainwater through a number of green methods, to reduce the flood risk. China started turning its cities into sponge cities – with promising results. Indonesia’s capital Jakarta is on its way to adopt the concept and Auckland, New Zealand’s largest metropolitan city, has set an example of being the “world’s spongiest city”. The path to making cities flood resilient is green.

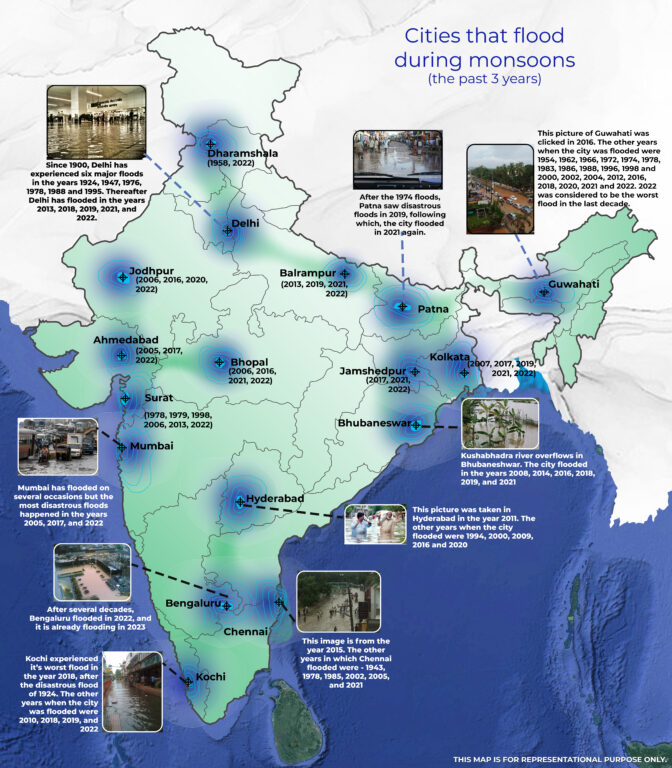

Map 1: India floods

This map is an illustration of how cities, large and small, across India have seen frequent floods and waterlogging in the last decade. Other cities and towns faced floods too. In 2022, the annual rainfall measured across India amounted to 1,257 millimetres; ten years earlier, the total was 1,054 millimetres. In the past few years, there have been cases of flash floods in cities that do not flood regularly.

In the past 122 years, New Delhi experienced six major floods in 1924, 1947, 1976, 1978, 1988 and 1995, but just the past decade has seen five major floods – in 2013, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022.[1] Bengaluru, despite its natural topography of rivers, valleys and lakes struggled through severe flooding in the last few years. After the 1974 inundation in Patna, the city witnessed disastrous floods in 2019 and 2021. In Guwahati, Chennai, Bhubaneswar, Kochi, Bhopal, Ahmedabad, and Surat — flooding has become more common.

Why are our cities flooding? There are different parameters for urban flooding, and for every city, the primary parameter might vary. These range from Climate Change to an increase in impervious surfaces in cities, encroachments on water bodies, increase in population and a spike in informal housing, poor land-use planning, geography and soil conditions, improperly-designed infrastructure, and inadequate drainage system. Why are our cities not draining themselves out? The answer is in how cities are constructed – more and more construction which disregards all else. The neglect and insensitivity have resulted in our cities turning into massive machine-infrastructures built upon land that has been tamed instead of being a part of the land.

To add to it, the drainage systems are poor. The stormwater system is disproportionate to the density of built spaces in newly-developed areas, the increase in untreated garbage and lack of desilting clogs drains, a lack of understanding of topography and hydrology while making urban development plans, rampant deforestation and encroachment of blue and green spaces. A city which is able to regulate and discharge rainwater would be a step closer to being sustainable.

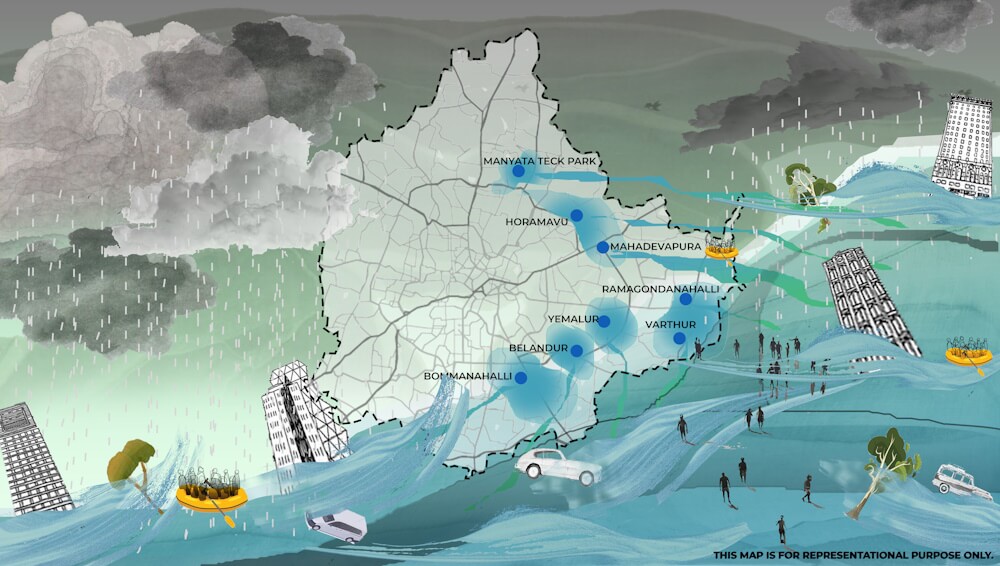

Map 2: Bengaluru

Bengaluru, which is situated in the rain shadow region of the Western Ghats, is part of an ancient wetland system. Bengaluru is located on a ridge which allows water to flow around it in three different directions.[2] Across the city, its once-interconnected lakes linked by canals or kaluves have turned into individual basins as their connection was snapped by parcelling of land and construction. In a heavy downpour, a lake that has excess water cannot transfer it to the next lake through the kaluves. This has happened due to the encroachment of lakes and stormwater drains for construction and real estate, polluting the water bodies with debris and untreated discharge, rendering them lifeless. Construction and concretisation does not allow water to percolate into the ground which has increased waterlogging in the city.

A study by Indian Institute of Science (IISc) found that there had been a 79 per cent reduction in water bodies and the number of lakes in Bengaluru in only 44 years between 1973 and 2017 while urban areas of Greater Bengaluru increased by a staggering 1,028 percent.[3]

In 2020, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) identified 211 flood-prone areas across the city, 58 severely vulnerable to flooding and 153 moderately vulnerable.[4] Bengaluru, with its interconnected lakes and kaluves could be a natural sponge city, if only it took immediate measures to conserve what is left of its natural areas and repair its ecology.

Map 3: Rotterdam

When it pours in Rotterdam, the city is barely affected because it was planned in ways that water would drain out. Instead of fighting the water, the Dutch have shown how to live with it, with minimum fatalities and disruptions. Rotterdam, the second largest city in the Netherlands which lies at the confluence of the rivers Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt, has 90 per cent of its area below sea level. The city was built by landfilling. Its name literally means, ‘the dam on the river Rotte’ but a spate of disasters including the flood of 1953, which took 1,800 lives, changed its direction. The government initiated the Delta Works (known as Deltawerken in Dutch) programme to avoid a once-in-a-100-year flood.

Later, in 1999, the city completed building a system of floodgates, called Maeslantkering, near the mouth of the North Sea to protect the city from storm surges and flooding. It is tested from time to time. From trying to fight off water by building levees and dikes, the city of Rotterdam has embraced its reality — of a city built on water that’s bound to flood. Its planning and design weaves in its topography. Rotterdam has built several water retention ponds across the city which help to collect rainwater and prevent waterlogging. These ponds have acted as floodplains. The new rowing course just outside Rotterdam, where the World Rowing Championships were held, is a part of the Eendragtspolder which is 22 acres of reclaimed fields and canals doubling as retention ponds. At 20 feet below sea level, it is among the lowest points in the Netherlands but, with bike paths and water sports, is a popular recreational space.

Besides, 0.33 square kilometres of the city’s 18.5 square kilometres of flat roof space was covered with green and the city is developing a ‘green-blue grid’. The idea is not just have green areas but also create reservoirs and tanks to retain excess runoff.[5] Dakpark, once a railway switching station and a neighbourhood infamous for drug dealers, is now a dyke with a shopping centre and roof park which slopes down.

In a bid to stay ahead of Climate Change, Rotterdam has opened the world’s largest floating office building alongside a floating farm, and a solar-powered Floating Pavilion in 2010 on its harbour.[6] The city also has an app with a GPS which tells residents exactly how far below sea level they are. Dutch children are also required to earn diplomas to certify that they can swim with their clothes and shoes on. All the measures show how a city built by landfilling can flood-proof itself with appropriate and sensitive urban design.

Map 4: Auckland

The term “sponge cities” is used to describe urban areas with abundant natural areas such as trees, lakes and parks or other good design intended to absorb rain and prevent flooding. (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change)[7]

The concept envisions urban areas with regenerated green spaces and water courses which can hold the rainwater or allow it a free flow while also effectively utilising it to mitigate flooding. Sponge cities have abundant natural areas such as trees, lakes and parks intended to absorb rain and prevent flooding; cities as diverse as Shanghai[8], New York[9]and Cardiff[10] are embracing their “sponginess” through inner-city gardens, improved river drainage and plant-edged sidewalks, according to this report.[11]

Auckland, in New Zealand, turned out to be the most spongy city in a survey conducted by the architecture-design firm, Arup, when compared to seven other cities in the world.[12]

New Zealand is prone to flooding when it rains. Auckland re-engineered pavements using gravel instead of tiles and cement to allow water to filter into soil, replaced empty lawns with native plants, and along the shore, planted trees to block the runoff. The city has engaged people to make Auckland more sustainable.[13]

How can cities turn into sponge cities? First, integrating green infrastructure such as permeable surfaces, green roofs, and urban wetlands to help absorb and retain rainwater, and reducing the surface runoff which is a key feature of the concept. This keeps the water from getting polluted as it travels to larger natural drains and allows water to seep into the ground where it has a tendency to collect itself.

Auckland has incorporated these nature-based solutions into urban planning, by emphasising such green infrastructure projects.[14] The city, like sponge cities of China, has also incorporated water-sensitive design practices by implementing sustainable drainage systems (SuDS). They employ techniques like rain gardens, bioswales, and retention ponds, hence allowing cities to manage their stormwater runoff at its source. This ensures minimising strain on drainage systems.[15]

Urban designer Yu Konjian first articulated the sponge city idea in 2012 after flooding wreaked havoc on dozens of cities in China. Shenzhen and Harbin are examples of China’s Sponge City Programme. Under the watchful eye of Kongjian and his firm which has carried out over 1,000 projects across 200 cities, the Bangkok Benjakitti Forest Park was spongi-fied and deemed a success; the sponge city model is improving day by day as the evidence base grows.[16]

Auckland has the highest sponge rating of 35 per cent followed by Nairobi and New York. Shanghai and London have also taken steps to turn into sponge cities.[17] In the United States of America, the two cities that are making headway in sustainable urban planning are Pittsburgh and Los Angeles. Cities are making permeable pavements, developing rain gardens, making vegetated swales which are essentially ditches filled with grass and plants that gather stormwater and help it seep into the ground. Los Angeles has its own story too.[18]

Maitreyee Rele graduated from School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) in 2021, where she mostly chose to work on projects on a larger urban scale. She is interested in studying people, their cultures and the society in which they unravel. An unfathomable love for films, art and every other form of storytelling make up the rest of the being.