The call on countries to “transition away from fossil fuels” is being celebrated as a historic outcome of COP28, the recently concluded annual UN-led climate conference in Dubai, UAE. Indeed, it was the first time that such a call has been made in any decision under the UNFCCC or the Paris Agreement,[1] and has been hailed by many quarters, especially developed countries as a key political success led by Dr Sultan Al Jaber, CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Corporation (ADNOC) and host of the 28th Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC.[2]

However, the truth is that once again, in the warmest year recorded in history, nearly 200 governments failed to arrive at a consensus to phase out fossil fuels, that is to stop extraction of coal, oil and gas to immediately and drastically reduce CO2 emissions, as informed by science and driven by the principles of equity and Common but Differentiated Responsibility (CBDR). The so-called first time ‘signal’ heralding the end of fossil fuel age, or the UAE Consensus,[3] the insipid outcome document of COP28, is nothing but a carefully crafted fable to hide the status quo agenda of the rich, powerful and fossil fuel-addicted nations and corporations.

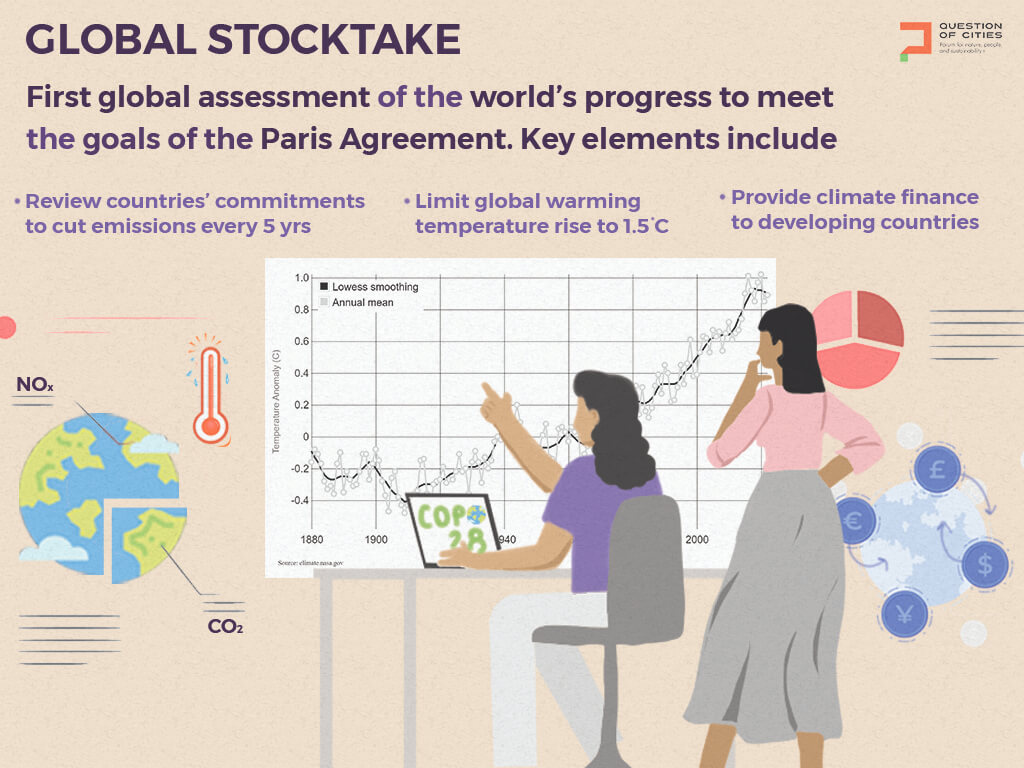

The Global Stocktake,[4] a core component of the Paris Agreement[5] was on top of the agenda of COP28 and involved an exhaustive appraisal of how far the world has come in tackling climate change and how far it still has to go. It is meant to be an assessment of mitigation and adaptation actions so far, as well as climate finance[6] provided and technology transferred from developed to developing countries, “in the light of equity and the best available science,” as per the Paris Agreement.

Over the past two years, governments, scientists and civil society groups have submitted[7] thousands of documents to conclude[8] that nations are not cutting emissions fast enough, they are not sufficiently prepared for climate hazards and developed countries are not providing enough support to developing countries. The GST synthesis report[9] concludes that there is a “rapidly narrowing window to raise ambition and implement existing commitments in order to limit warming to 1.5C”. Achieving the 1.5C target, or even the “well below 2C” goal, requires nations to fill the extensive “implementation gaps” between their climate strategies and real-world action.

Illustration: Shivani Dave

Victory for fossil fuel industry

This is where Dubai disappointed, even as it finally acknowledges the role of fossil fuels in the climate crises after nearly 30 years of knowing, ultimately the COP28 only “call[ed] on” all countries “to contribute to” a list of goals, including “transitioning away from fossil fuels…accelerating action in this critical decade”, which is way short of a clear and time-bound commitment to “phase-out [10] fossil fuels” that is needed to stay below 1.5C[11].

What is worse is the final outcome while giving a free pass to gas and oil as transitional fuels, it goes on to urge countries to “phase-down unabated coal power,” which is coalspeak for promoting carbon capture storage and other ‘technologies applied or measures taken to reduce pollution and/or its impacts on the environment[12]. The most commonly used technologies are scrubbers, noise mufflers, filters, incinerators, waste—water treatment facilities and composting of wastes, none that have proven to make any real difference in emission reductions.

Essentially, an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels with no plan, no clear financial commitments and no timescale is not, by any stretch of the imagination, something to celebrate about. This was a victory for the fossil fuel industry, not for the world.

While the decision on the ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’ in the Global Stocktake took most of the limelight especially in relation to mitigation, less attention was paid to the decision[13] on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), where Parties struggled to find consensus on the GGA framework. For many countries, adaptation is a matter of survival. COP28 failed to send a strong political signal on the need to ramp up both adaptation action and support for developing countries in enhancing adaptation and no accountability in tracking and assessing the support provided.

The consolation Fund

The only success worth celebrating, and the credit goes to Dr Sultan Al Jaber, for his diplomatic coup to get countries to agree on the decision to operationalise the Loss and Damage Fund on the first day of the COP28. “Loss and damage”[14] is a term used to describe the unstoppable harm caused by climate disasters. For more than[15] 30 years, small-island states in particular, have been fighting[16] for funds to help them deal with everything from hurricane damage to sea-level rise.

Countries agreed in Dubai that the fund would be housed in the World Bank for at least four years, but it would also be an independent entity under the UNFCCC’s financial mechanism. Incidentally, unlike other forms of climate finance,[17] there is no firm obligation for developed countries to pay into the fund. It will, therefore, depend on the generosity of wealthy nations. A total of $770.6 million was pledged by a few rich countries by the end of COP28. With $115.3 million earmarked for setting up the fund, the money pledged so far would cover less than 0.2 percent of the developing countries’ annual needs.[18]

Meanwhile, on the sidelines of negotiations, 130 governments launched a new initiative[19] to boost renewable energy and energy efficiency. The initiative sets a global target to triple installed capacity to at least 11 terawatts (TW) by 2030 and double the rate of global energy-efficiency improvements, from roughly 2 to 4 percent per year, by the end of the decade. The announcement was broadly welcomed, but many highlighted that the growth of renewables “must go hand in hand with a full fossil fuel phase out”.

India, it must be noted, is not a signatory to the initiative. The energy breakdown makes it clear why – coal is the country’s top energy source with a share of 55 percent in 2022, according to the Union ministry of coal; this is followed by oil at 24 percent. An analysis[20] by researchers at Climate Action Tracker described the pledge as a “key highlight” of COP28, saying it could “close about a third of the gap between current policies and 1.5C in 2030 if fully implemented”.

Photo: Shailendra Yashwant

Importance to multi-level initiatives

In other positive developments, there is strong momentum behind national governments committing to integrate subnational governments into their climate strategies under the CHAMP (Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnerships)[21] for Climate Action initiative. Across both NDCs and Adaptation Plans, there is now recognition in the COP agreement about the importance of multi-level partnerships in delivering them, while the operationalisation of the Loss and Damage Fund includes recognition of cities as a venue for direct access to funding.

For too long, city representatives have been arguing for multi-level green deal governance and for revising the governance and regulation of energy and climate action. Likewise, some European city groups have been staunchly advocating for direct actions in cities. For the first time ever, cities had a seat at the COP table and thanks to that nearly 70 countries have committed to work with local leaders on the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) due in 2025 ahead of COP30 in Brazil, and, countries will for the first time be required to deliver National Adaptation Plans alongside them. The final COP28 agreement reflects growing understanding of cities as critical climate battlegrounds and partners for action — a fitting recognition since 70 percent of CO2 comes from urban areas.

In the end, many will remember COP28 in the oil-producing nation of UAE as the most controversial of all the COPs, but so was COP26 in Scotland and so will be the COP29 to be held in Baku, Azerbaijan, next year. These are fossil fuel producing nations; it is in their interest to keep drilling and selling the fossil fuels which makes it highly ironic, also a clear conflict of interest, for them to discuss action against climate change.

Who sat at the table

There are many who believe that no fossil fuel lobbyist or company representative, let alone leaders of the business, should be in the COP negotiating rooms. Many want the fossil fuel producing nations to be gagged at COP. As Marta Schaaf of Amnesty International puts it “Arms dealers are not asked to peace talks, so it is warped to ask climate wreckers for their view on how to fix the damage they have caused.” Others point out how multilateral processes do not work like that. Many believe that we cannot solve the problem without including the people who are part of the problem; not having them might mean that the COP process is dead.

However, COP28 broke all records in giving access to fossil fuel lobbyists. Controversy had gripped COP28 even before it started, with the appointment of Dr Sultan Al Jaber, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, as the president of the conference. It did not help matters when a leaked letter from Haitham Al Ghais, secretary general, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, urged 13 of its members to reject any text targeting fossil fuels and to top it the controversial statement by Dr Al Jaber when he said that there was “no science” to justify the phase out of fossil fuels to restrict global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

According to the advocacy group Kick Big Polluters Out,[22] the number of industry representatives pushing the case for fossil fuels at COP28 had nearly quintupled[23] in the past three years. In 2021, at the COP26 gathering[24] in Glasgow, Scotland, there were 503 fossil fuel lobbyists present. That increased to 636 at COP27[25] in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, last year before ballooning to a whopping 2,456 this year in Dubai.

At least 80 of the 200 countries at COP28 were demanding ‘fossil fuel phase-out’ language in the run-up to the final text of the UAE outcome. Despite this, when it came to the final consensus, the handful of the world’s powerful prevailed and the world missed another opportunity to strike at the core of the climate crises.

Photo: ‘Climate Change: America and the World’ by the Phelan US Center, exhibited at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Inclusivity and justice on COP agenda

Climate discussions and agreements may sound like word salads but the focus has to be on people’s lives and rights, on climate justice and inequality. This takes the COP discussion into the arena of human rights and should ideally have reflected during the summit, but it did not, given its domination by western businesses, society, and media. The COP28 had nearly 80,000 people in attendance; the assumption is that there was fair representation of all people and nations. This was not the case.

As it is such spaces are not designed for inclusivity or justice-speak. It is well known that many civil society representatives and even government delegations from the worst-affected nations cannot travel to these summits because of travel costs and accommodation. No COP can claim to have a full representation of the world. Moreover, the UAE’s criminalisation of freedom of assembly, closure of civic space, and repression of critics limited meaningful participation of activists and human rights defenders in climate negotiations.

Climate activists were unable to march outside of the official COP28 venue as protests are illegal in the UAE, unlike at previous UN climate summits such as COP26 in Glasgow where thousands of climate activists rallied in the streets. Advocacy actions and protests within the UN-run “blue zone” were also severely limited, with unprecedented restrictions on freedom of speech from the UNFCCC Secretariat.

And yet, activists organised a protest march with over 100 participants and a people’s plenary calling for a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war. Across the civil society space, in demonstrations and people’s interventions, solidarity was expressed with the Palestinians. It was an important message not often heard in these corridors. The fact is that war and militarisation – which are about oil and gas too – are big contributors to climate injustice..

The talk of climate justice is still in the corridors, but it will, hopefully, make its way to the main halls soon. The way civil society groups from around the world made the connection between the two at this COP was extremely powerful. This fosters hope that international forums will not have silos; that we can talk about the economy, ecology and urban question in an inter-connected way.

Shailendra Yashwant is an environmental journalist, documentary photographer, and campaigns consultant based in India. He works on climate change-related mitigation, adaptation and projects and policy-making initiatives at national and international levels. He is a Senior Advisor to Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) and a steering committee member of the Pesticide Action Network (India).

Cover photo: Shailendra Yashwant