The 27th Climate Conference of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or COP27, at Sharm el-Sheikh was billed mainly as “the implementation COP.” People expected concrete decisions about rapid transition to non-carbon energy sources to achieve the temperature-rise goals set in the Paris Agreement. Additionally, developing countries expected that a Loss and Damage fund would be set up to ‘compensate’ the poorer countries to make good the adverse impact of Climate Change.

The principle of climate justice and historical climate debt by the rich developed countries to the poorer developing countries is a globally accepted one. It was enshrined as CBDR-RC (Common But Differentiated Responsibilities with Respective Capacities); it meant that while all countries are responsible to tackle the climate crisis, the developed richer countries have a greater responsibility as they have been primary contributors to the atmospheric emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) leading to Climate Change, and they have more financial and technological capacities too. Therefore, developed countries must provide financial and technological assistance to developing countries – not as charity but as their responsibility.

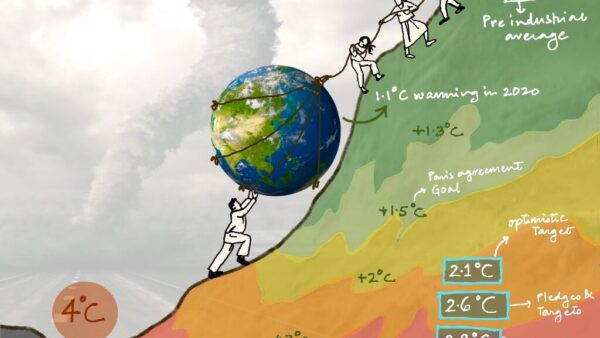

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its latest Climate Change Assessment Round 6 (AR6). Its Working Group 1 report released before COP26 assessed, among other things, the trends of current global Climate Change; Working Group 2 and 3 reports were released in early 2022. All the three showed that human enterprises were far from being on course to achieve the Paris Agreement goals; faster and stronger actions were urgently needed.

As more people now live in cities than in rural areas globally, and cities with roughly 55 per cent of the global population contribute nearly 70 per cent of the total greenhouse gas emissions, what happens in and to the cities is extremely important for Climate Change. Even in India, billed as a “country that lives in its villages”, nearly 35-38 per cent – or nearly 500 million – people live in cities. Cities, despite better economic and technological resources, are necessarily denser habitats with fewer natural commons to absorb the climate-related extremes. The tier-II and tier-III cities are overcrowded and ill-prepared to face any climatic extremes. So, what happened at COP27 mattered because it filters down to the last person in our cities.

The background

The COP27 elicited a great deal of interest worldwide but did not go the distance it could have to make good the global agreement arrived at COP21 in 2015 in Paris to “keep the global mean annual temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial average temperature, and to keep this rise within 1.5 degrees Celsius”. Most major economies including India had submitted their climate action plans till 2030. Known as the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the plans chart the pathways each country intends to take to tackle the climate crisis.

While major greenhouse gas emitting nations focused on reducing the emissions with mitigation-adaptation actions, smaller countries focused on the adaptation aspects. India being the third-largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter, its plans heavily leaned on reducing emissions as well as absorbing some of the emitted carbon dioxide. The first was to be achieved by reducing the emission intensity of GHG as well as increasing the percentage of non-carbon/non-fossil energy sources in its energy mix.

Photo: Thejas/ Creative Commons

Phase out coal before all fossil fuels

In August this year, India launched the Long-Term Low Emission Development Strategy (LT-LED) to guide the country towards low emissions. However, there is no clear guidance to states and cities on how to move ahead; moreover, this is not a detailed plan.

When the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) was drafted in 2008, some of us criticised it saying it was more a wishful statement than a plan. The then Manmohan Singh government argued that it was only a guiding principle. Guidance strategy has limited value. The only two missions of the Plan that have been reasonably successful are the National Solar Mission and the National Mission for Enhanced Energy Efficiency. Despite the intervening years, there is little clarity on how the government plots its next few moves for cities.

At COP27 this year, India played the game of phasing out all fossil fuels, in itself a legitimate goal, but India proposed this knowing that rich developed countries would not accept phasing out oil and gas. My understanding is India is not ready to phase out all fossil fuels; in fact, it is not ready to even phase out coal, let alone all fossil fuels. India wants to focus on public transport and electric cars to reduce fossil fuel use. How can electric vehicles (EVs) solve the problem when electricity is coming from coal? Besides, how many people can afford the EVs anyway?

Photo: IAEA Imagebank/ Creative Commons

Central government holds the key

I propose two feasible solutions: Phase out the 25 to 30-year-old coal power plants and put high emphasis on public transport. As power plants age, they become costly to run and become polluters. Indian cities should use railway lines instead of building expensive metro networks. Delhi has a good railway grid but it has been neglected on purpose. Also, CNG buses are affordable and their strength needs to be ramped up. Delhi was estimated to need 11,000 public buses; it has around 6,000 but the Aam Aadmi Party government has not added even 1,000 more. Thousands of crores spent on flyovers could have been used to buy buses.

For climate action in cities and otherwise, the buck stops with the central government. Most state governments and urban local bodies do not have the budgets to finance climate-smart solutions. The Centre has to come up with reasonable plans. In 2011, it had told the state governments to chalk out their climate action plans. States like Odisha enthusiastically unveiled big plans but the Centre said it could not fund the plan.

Many cities like Jaipur do not need the expensive metro rail network which costs Rs 300 crore to construct every kilometre; it becomes a tourist attraction, no more. A whopping Rs1.10 lakh crore has been earmarked for the bullet train; the money could have funded upgradation of public transport in 25 cities. The central government has to support projects in cities which use public funds or tax money for low-cost and ecologically-friendly urban transport. This is the most basic step to take.

The central government has to be accountable to the public and people need to hold it to account on climate, which is not happening.

Coal phase-out arguments at COP27

The Conference was expected to firmly put the world economies, especially the G20 (Group of 20 largest economies), which emit more than 78 per cent of the total greenhouse gases, on the course to rapidly shift away from fossil fuels. This called for concrete plans with timelines.

In the COP26 at Glasgow in November 2021, there was a selective proposal by the rich developed countries to adopt a resolution to “phase-out coal” within a short time span because coal is the most polluting of all fossil fuels. The economies of the developed countries already moved to a much higher dependence on oil and gas, renewable, nuclear and so on; they rely less on coal. In developing countries such as China, India, and Indonesia, the dependence on coal is overwhelming. Expectedly, China and India strongly opposed the move. Finally, a diluted text was adopted. In Sharm el-Sheikh, a similar failure to adopt any new progressive measure to shift the world’s economies from climate-threatening fossil fuels to non-carbon sources of energy has meant a chaotic climate for all. And because cities house millions of people in congested and inhospitable manner, the impact is bound to be worse.

A proposal moved by India and supported by the G77 and China – the largest country grouping in the UNFCCC – to “phase out all fossil fuels” was strongly opposed by the rich developed countries; it fell through. As a negotiation tactic, this was a smart move by India to relieve the selective pressure on coal, but as a climate outcome, this is an unmitigated disaster-in-waiting. Now, there is effectively no decision on the urgent action of phasing out all fossil fuels.

The only positive development, possibly as a bargaining tactic by the developed countries, was their willingness to green-light the Loss and Damage Fund to provide climate finance to developing countries. But, at this point, it is an empty fund with no money promised by anyone, even the modalities and operating framework are yet to be decided.

Major economies of the world failed to take a decision to decisively move away from the climate-disrupting fossil fuels. What is the reason? For that, look at the enormous money and political influence of the world’s fossil fuel companies, over 635 of whom were present at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, actively influencing government delegates. The profits of these companies took priority over billions of people suffering ever more from the increasing Climate Change impact. It’s not only us humans, but around one million other species of life are seriously threatened too and face extinction over the next few decades due to Climate Change threats.

Photo: Indrajit Das/Creative Commons

What lies ahead for cities in India

Millions of Indians have suffered various kinds of losses and damages in the extreme climate events. Flooding was unknown in the rain shadow areas of Sangli, Satara, Kolhapur in Maharashtra, but these districts experienced incessant rainfall and devastating floods last year. Maharashtra suffered the most recorded deaths – 350 – in 2021 due to extreme events, according to an analysis by the Centre for Science and Environment. Odisha registered 223 casualties. [1]

The massive flooding almost submerged well-drained cities and towns in the Konkan region of Maharashtra like Chiplun. The coastal cities and villages of West Bengal were severely hit by Cyclone Amphan in May 2020 which destroyed lakhs of homes, and by Cyclone Yaas in May 2021. The western coast, facing the Arabian Sea, was relatively calm and safer from cyclones for decades. However, over the past four years, the coastal cities, towns, and villages have been hit by four cyclones, an unusual occurrence. Even mega cities like Mumbai are now regularly disrupted by Climate Change-driven heavy rains, flooding, and cyclonic damages. All these are set to intensify in cities across India.

In 2022, India recorded six heat waves — an unprecedented occurrence. Thousands have died but official figures linking these deaths to climate events are scarce. Delhi reached a searing 49 degrees Celsius on a couple of days, some places in Rajasthan and Haryana exceeded 50 degrees Celsius for a few days. The impact is not uniform across all who live in cities – construction workers fainted of exhaustion while contractors accused them of laziness, crores of street vendors braced the burning temperatures.

The IMD reported that “the past decade (2011-2020 and 2012-2021) was India’s warmest decade on record”. And 11 of the recorded 15 warmest years occurred within the past 15 years. Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Gujarat and Haryana accounted for about 54 per cent of the total heat wave days in India in 2022. The predictions are that by 2050, heat wave incidents might increase four-fold if today’s emissions continue. Imagine the toll on the urban poor.

Who bears the brunt?

This is the core of the problem in India. While urban middle and upper classes have resources to cope with the increasing impact of severe heat-waves and massive flooding or foul air, the urban poor are paying the highest price – the six to seven crore construction workers in brutal heat, three to four crore street vendors, rickshaw pullers, porters, even traffic police personnel.

It’s not only the heat. When a city gets intense and heavy rains, and gets flooded, the low-lying areas and the drainage channels are inundated with sewage and dirty water; and there are landslides. Urban floods are not unique to some cities, they are now a national problem affecting millions of people in mega cities every year. Ahmedabad, a traditionally low-rainfall area, was inundated by July 2022.

As floods battered cities, few noticed the sharp increase in incidences of both urban and forest fires in 2022. As reported by the forest survey, an unprecedented 1,36,000 incidents of fires were recorded in India, just in the first four months of 2022, although peak summer was yet to start. In the cities, it is again the urban poor whose hutments, slums, and jhuggies went up in flames again and again.

Cities stare at increase in pollution

The other major challenge that Indian cities – already bearing the burden of some of the world’s worst Air Quality Indices (AQI) — is the continuation and likely increase in air pollution. This is now a given as the “coal phase-out” proposal was rejected. Coal being a major contributor to both particulate and gaseous air pollution as well as major water polluter, if its usage increases, so will the air and water pollution. Moreover, coal power is one of the biggest water guzzlers. With Climate Change creating erratic patterns in the monsoon – which is the source of 74 per cent of India’s fresh water supply – water shortage is getting worse by the year and will continue. Heat and water shortages together is a recipe for a perfect climate disaster.

What are our cities doing? Ahmedabad came out with a Heat Action Plan years ago, after over a thousand of its citizens lost their lives in one of the worst heat waves. Other large cities followed suit. Some have made a separate flood action plan. States now have their second edition of the State Action Plan for Climate Change. Unfortunately, the plans have hardly any ground-level inputs from the real stakeholders – construction workers, rickshaw pullers, street vendors, porters, waste workers.

Most of the plans are heavy on post-disaster responses like rescue and relief, which have a glamour element attached. While the National Disaster Management Act 2005 along with its National and State Disaster Management Authorities is under the all-powerful Ministry of Home Affairs, the State Action Plans on Climate Change are under the lightweight ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change. Does the big brother care to consult with the weak sibling?

But where are the ‘plans’ that really look ahead, take risk minimising actions, and focus on building adaptation capacities among the communities suffering the most from these climate extremes? It’s not only that the COP27 failed but, as a result, governments are not constrained to urgently adopt mitigation-adaptation measures or prepare for people to brace climate events. This is the biggest threat – climate or otherwise.

Soumya Dutta is a veteran people’s science activist working on Climate Change, energy and other ecological issues. He works extensively with many working-class communities and unions in India. Dutta is an advisory board member of UN Climate Technology Centre and Network; co-convener of South Asian People’s Action on Climate Crisis SAPACC; and part of climate & energy group, MAUSAM Trust.

Cover photo: wwf_france/ Creative Commons