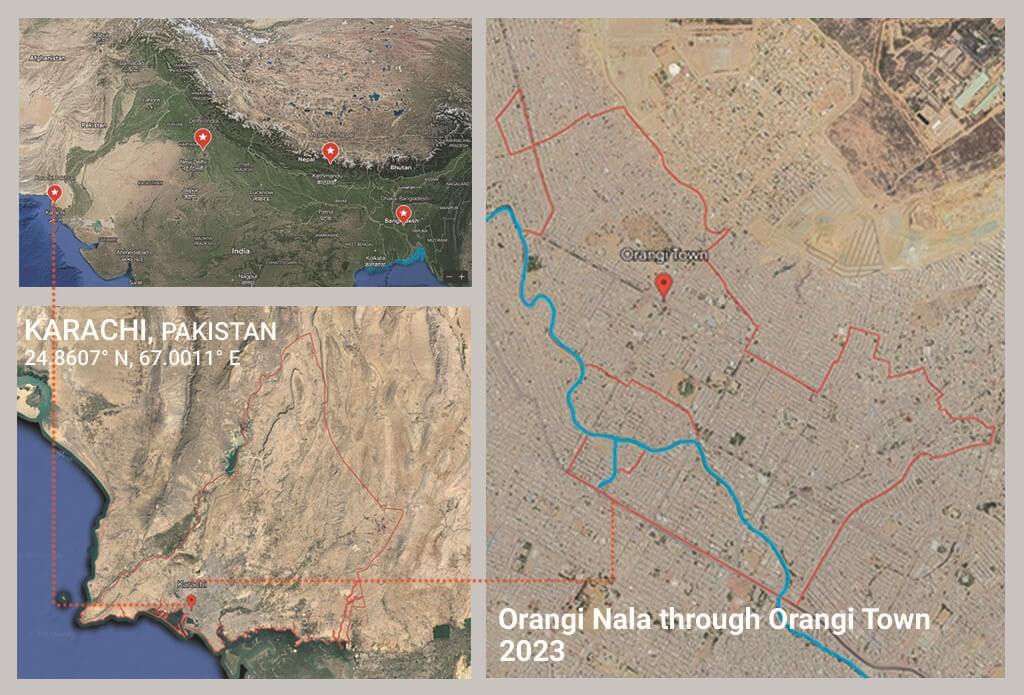

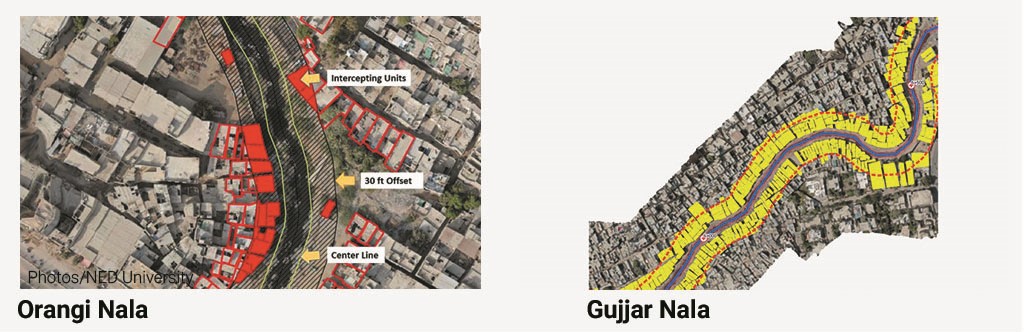

For three years and as many monsoons now, 40-year-old Ambreen Naz has struggled to live her life in a partially demolished house by Thorani Goth, along the Orangi Nala in Karachi, Pakistan. The Nala, a small stream which flows through the city towards Arabian Sea, spawned the Orangi Town, Pakistan’s largest slum with an estimated 2.4 million[1] people living in it. Naz’s house was among the 1,721 of the 6,932 houses along the city’s three nalas – Orangi, Gujjar and Mehmoodabad – partially demolished by the Sindh government on the orders of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, in April 2021, as a measure to control and combat ferocious floods.

Large-scale slum demolition as a flood-control measure gained legitimacy as parts of the settlement in Orangi Town were, and continue to be, illegal. The demolition was mandated by the country’s highest court almost a year after the devastating floods in Karachi, Pakistan’s financial hub with a population of more than 16 million of which half live in informal squatter settlements called katchi abadis. In August 2020, a staggering 484 millimetres[2] of rain led to the submergence of vast areas of the city. The water did not drain out. The culprit, in popular imagination and official perception, were the settlements in Orangi Town, especially the illegal ones.

The monsoon has been particularly harsh on Karachi except in 2021. In 2019, 2020 and 2022, it rained 352.8mm, 520mm and 493mm respectively between July and September, according to the Pakistan Meteorological Department’s records. Dr Sardar Sarfaraz, the chief meteorologist confirmed “these are climate-related catastrophes that we are experiencing…the rise in global temperature is causing these intense bouts of rainfall.”

Map: Shivani Dave

As weather events triggered by Climate Change intensify across Asia[3] including Pakistan, cities like Karachi have witnessed massive flooding. Building flood control and resilience have become critical to the city but the axe has fallen on its poorest living without the security of shelter. Does it have to be so?

Whither rehabilitation?

The Supreme Court, while ordering demolition, had asked for rehabilitating the evicted along the Orangi Nala. Pushed to uphold this, the Sindh government prepared a resettlement plan for the nearly 7,000 households estimated at PKR 10 billion[4]. Each household would be given an 80 square yard plot and financial assistance to build a home but in Malir district, nearly 30 kilometres away, where the government had acquired 248 acres land for the purpose. This did not impress many of the evicted.

“It’s a house for a house but I will not move to a place smaller than what I have,” said a vexed Naz, terming the deal “unfair” because her partially-demolished house stood on 120 square yards. She wanted the new home “to be in the same district and of the same size”. The lack of confidence in the government’s relocation plan stems from the fact that no meetings were held with the distressed. “We have no communication, formally,” said Arsalan Anjum, 37, community spokesperson and member of the Orangi Nala Mutasireen Committee (ONMC).

Two years later, as people like Naz use a giant red tarp to cover the enormous cavity which was once the rear wall of her house and deal with hazards such as rats biting her sons while they were asleep at night, rehabilitation is hanging fire. This August 18, the Supreme Court finally took notice. Hearing a petition filed by the affected[5] against the former chief minister for not complying with the court’s directives to pay PKR 3,60,000 in four tranches – only two tranches of Rs 90,000 each were released before payment was stopped – the court ordered the release of the unpaid amount within 30 days.

Along Orangi Nala, the affected people are delighted with this small win, that they will get the unpaid amount they desperately need. They know the resettlement and rehabilitation plan remains to be implemented but the uncertainty around it has increased. The Chief Justice who ordered it has retired, the chief minister is no longer in the chair, and officers in the Karachi Municipal Corporation are being frequently transferred.

In the resettlement plan, the government offered two alternatives[6] but no decision has been taken even two years after the demolition. The government could release a lump sum to the affected to purchase 80 square yards land and construct a house based on the market value of the place from where they were evicted, or hand over the plots in Malir to each affected household and pay for the cost of construction as per the standards set by the Pakistan Engineering Council.

Neither has materialised. For the nearly 7,000 households comprising no less than 65,000 people, their future remains as uncertain as it was when the flood waters rose in 2020 followed by the bulldozers which tore into their homes. Along with their homes, their livelihoods too took a blow then; many families are yet to recover from the total impact.

Master Plan needed

Indeed, Karachi’s future is uncertain given the gap between what the city needs – a comprehensive urban plan with adaptation to Climate Change – and what it has now which includes disorganised policies, chaotic under-funded programmes such as nala cleaning, multiple agencies and government structures. This is a recipe for possibly greater disasters in the years ahead as the frequency and intensity of floods increase. There is no doubt that Karachi needs a comprehensive Master Plan with climate adaptability.

“…With the rise in Earth’s surface temperature driving climate change, future perturbations in local weather events in Karachi are predicted…In August 2020, Karachi received more than 8 inches, over 20 cm, of monsoon rainfall which is the estimated amount of rainfall in Karachi in one year. Flooding is particularly perilous for vulnerable infrastructure, especially financially unstable citizens who reside in impoverished neighbourhoods with poorly constructed homes…It is evident that climate change is exacerbating floods, droughts and wildfires in Karachi,” observed this scientific study[7]

It also pointed out that the “transmissibility of infectious diseases, air pollution, and adverse health outcomes are all consequences of Climate Change that have occurred in the city of Karachi. The ongoing damage due to Climate Change on the city’s environmental, and social structures are leaving the city’s vulnerable citizens plagued with illness. The clear implications of climate change pose a major threat for public health”.

Mohammad Yunus, director of the Urban Resource Centre, a non-governmental organisation, recalled that 20-30 years ago the monsoon rainfall was light but continued for weeks allowing the water enough time to flow out. “Now, we have a weeks’ worth of rain in a couple of hours,” he said, adding that the water had no passage to flow out. Yunus warned “climate-related downpours will become even more unmanageable in times to come”.

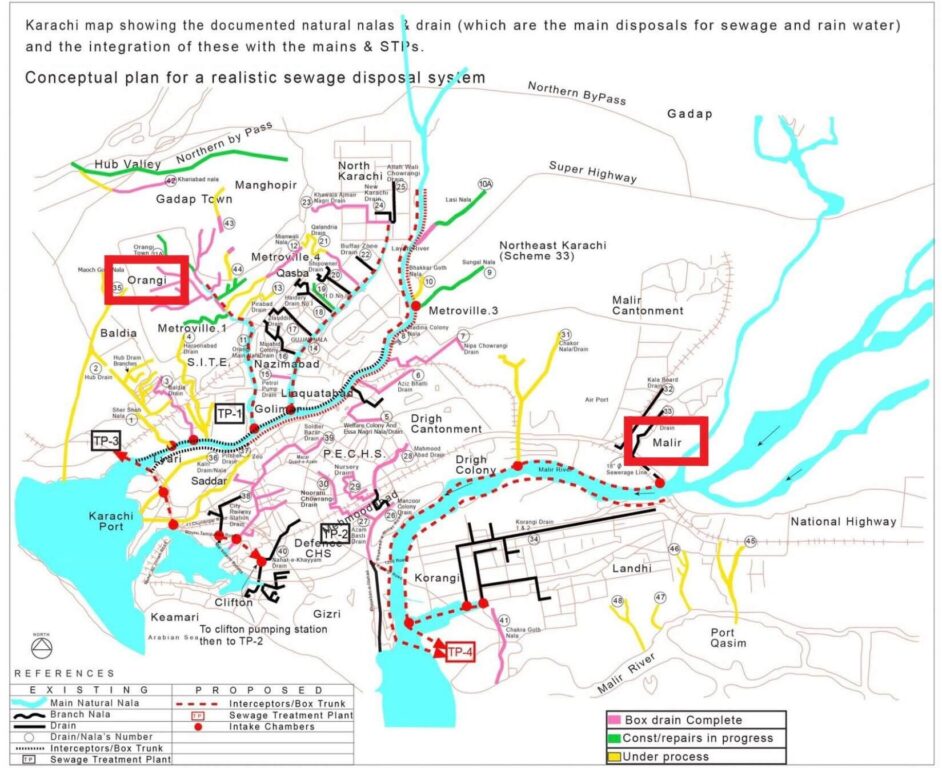

Karachi with its hotchpotch of buildings and thousands of kilometres of impermeable asphalt roads cannot absorb the rainwater. Nor can the 550[8] or so big nalas (the biggest being Orangi, Gujjar and Manzoor Colony nalas) and small constricted stormwater drains already filled with solid waste and wastewater carrying water into Malir and Lyari rivers, both of which rise on the foothills of the Kirthar range and run parallel about 14-20 kilometres apart to flow into the Arabian Sea.

According to Dr Noman Ahmed, dean of the Architecture and Management Sciences at Karachi’s NED University: “Land formations such as natural hills, hillocks and water bodies are either levelled or reclaimed to enhance footprint of commercial development. Our policies, programmes and projects have very little consideration for climate-related initiatives.” The response, as it did after the flooding in 2020, was to remove illegal settlements along the Orangi Nala. Now, the Nala has undergone a makeover with walls and roads constructed along both sides of the waterway, but the homes that were razed remain in the same condition.

The top court’s order to rehabilitate “preferably within one year” has been conveniently forgotten. Even the petition filed by over 40 civil society organisations against the Sindh government’s contempt of court, for refusing to follow Supreme Court’s orders, has failed to pressurise the government.

Nala cleaning and climate justice

Nala cleaning was deemed a top priority after the floods. However, “it is a temporary relief,” said Mohammad Yunus. With Karachi generating 13,000 tonnes[9] of garbage every day, nalas get clogged repeatedly in the absence of a proper solid waste disposal system. Nala cleaning has helped flood control to some extent in the past two years but governments have to put in a sewerage treatment network too.

“During normal rains, the existing stormwater drains can work efficiently if solid waste dumping is controlled,” said a senior Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB)[10] spokesperson but the water channels are insufficient for “intense downpour as a result of climate aberration”. Residents along the nala throw garbage into the drains. “People know the consequences but there’s no disposal system,” said Mohammad Ismail, 45, who had a stitching centre in his home employing eight people.

Ismail’s story of the flood echoes across Orangi Town. “During the 2020 floods, water entered my home. My wife and I, in chest-deep water, tried to salvage the eight machines I had bought but the damage was done. Then, the authorities broke down most of my home,” recounted Ismail. He now works as a daily wage earner at a clothes factory. “From 3,000-4,000 rupees a day, my earning is down to 400-700…it’s a dog’s life.” Although he received PKR 1,80,000 as compensation, he remains in debt given the galloping cost of living. Pakistan’s inflation was at a record 36.4 percent this year, the highest in South Asia[11], mainly due to food prices, according to Reuters.

The ONMC stated that it was “unfair” that a household was not recompensed based on the damage and loss, and unfortunate that the drone survey carried out to establish the number of homes to be demolished was faulty. “People should have been provided with an alternative before the anti-encroachment drive,” said architect and urban planner, Arif Hasan.

Karachi’s stormwater drains were not always like this. About four decades ago, the water was clearer but now, along with the solid waste, more than 400 million gallons per day (mgd) of wastewater flows into them. According to the 2019 World Wildlife Fund-Pakistan report[12], Karachi produces around 475 mgd of wastewater, of which 88 percent flows into the Arabian Sea – untreated – despite having three effluent treatment plants.

In the Orangi Nala, as in others, the affected people also paid for the cleaning. The newly-constructed walls hide the sludge but stench fills the air. The walls prevented the overflow into the slum during heavy rainfall last year, but little else. We would be “chest-deep in muck, our belongings floating in the filthy water,” Naz recalled the rainy days before 2021. Residents like her do not have money to rebuild their homes. “There are days when we don’t have enough to eat,” she whispered.

Family relationships are at stake too. Asghar Ali, 19, said his parents worked hard and his mother sold her jewellery to upgrade their tenement, but the 2021 demolition turned it to rubble which they see, heartbroken, from their one-room rented quarter. “I can’t bear to see my mother crying, she does that all the time,” said Ali, who started working in a lathe factory while still in college. “The atmosphere at home is always sombre…happy days are over for us,” he said, reminiscing how the family of six would gather at tea.

Climate and Karachi Master Plan

There should be no doubt now that the Karachi Master Plan has to prepare for climate adaptation and it would have to factor in social justice, given that climate policies can improve or worsen the lives of the poor. “What Climate Change has done, metaphorically speaking, is to set the cat among the pigeons. We will have to ensure that social justice is a key pillar of our response. Climate policies that make one segment of the population better off at the expense of another more vulnerable segment, are in essence, enhancing climate risks that will only make cities, like Karachi, collectively less resilient,” warned Imran Saqib Khalid, climate governance expert at the WWF-Pakistan.

As climate catastrophes like floods turn into life threatening multipliers for those directly affected – damaged homes, job losses, rising debt, increased school dropouts and adverse health impacts – climate adaptation in Karachi, and other cities across Pakistan, has to necessarily mean climate justice. To do this, the governments at various tiers must sink their political differences and approach the task with a mix of science and empathy.

Without substantive policies and steps devoted to climate adaptation and environmental development, the Master Plan for Karachi would have limited relevance. For example, the city’s natural water channels do the job of sewers and the stormwater drains are unable to handle the load of water when it rains as it did in 2020 and again in 2022. The Master Plan would also need to carry out a flood risk assessment to identify and understand current as well as likely flood impact in the future. However, there is no assurance that it has mapped the locations badly impacted by past floods.

A flood map well-grounded in academic studies as well as lived experiences would help to also develop an early warning system for people. This is essential if Karachi has to secure its residents against rising incidences of fierce floods. Equally important is that the Master Plan recognise and mark out the floodplains of the rivers and streams, and do not allow any new development on them.

All this would call for the national, state and city governments to collectively join the dots between Climate Change and issues on the ground, and distil the learning into the Master Plan. However, with political conflicts between the three governments and their tendency to firefight one problem after another, this is a tall order.

Zofeen T Ebrahim is an independent journalist who has written extensively on development issues including Climate Change, urban infrastructure, water, energy, gender, and how these impact our lives. She contributes regularly to English daily, Dawn , The Guardian, The Third Pole, Thomson Reuters Foundation, and Index on Censorship.

This is the first part of a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship to report on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia.

Cover photo: Ambreen Naz stands near her demolished house in Orangi Town, Karachi.

Photos: Zofeen T Ebrahim