Between January 29 and February 8, 2023, Mumbai ranked as the “world’s second-most polluted city” in the global Air Quality Index. In 2021, the city ranked 124 in the world air quality report. The deteriorating air quality was starkly evident in the blanket of smog which the city woke up to through the months of January and February.

Mumbai, which boasts of a long sea coast, has overtaken the landlocked Delhi in the list of the most-polluted cities in the world. The argument that the Mumbai’s bad air quality is buffered by the sea no longer holds water. The city’s air quality has been fluctuating from ‘poor’ to ‘very poor’, and residents cannot breathe easy. The term ‘AQI’ has now been added to the Mumbaikars’ regular talk.

Air Quality Index or ‘how bad is our air’

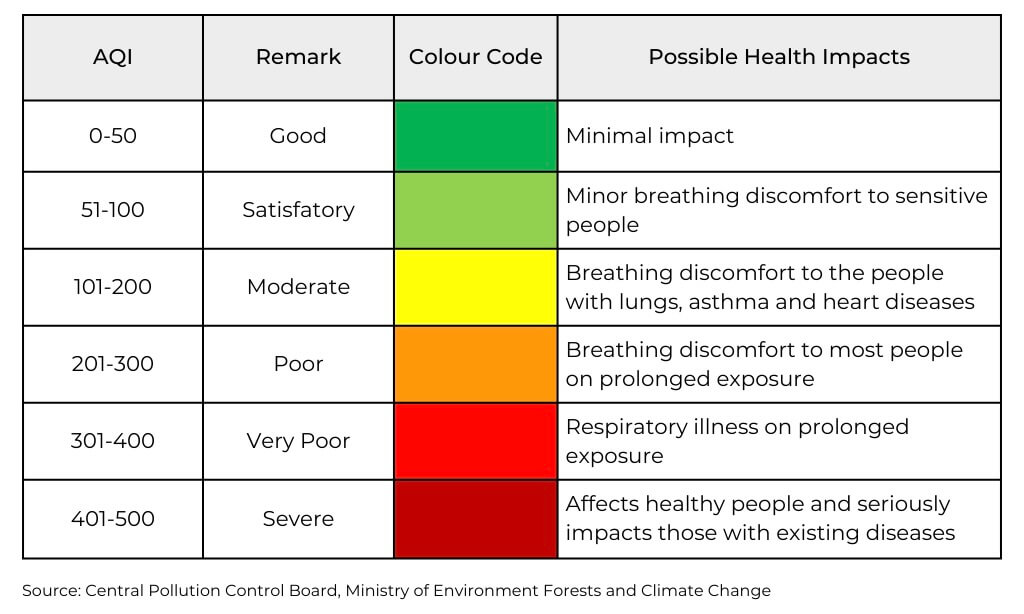

Launched in 2015, Air Quality Index or AQI is a number showing the quality of air in an area. It is an indicator of air quality, and records the levels of multiple pollutants in the area. It transforms complex air quality data of eight pollutants into a single number.

The eight pollutants that are monitored for their concentration to calculate the AQI of an area: Particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, ground-level ozone, ammonia, and lead.

How is AQI calculated?

The sub-indices[1] (concentration) of individual pollutants contributing to the overall AQI at a particular monitoring station are calculated using their average concentration value over a 24-hour period (eight hours in case of carbon monoxide and ozone) and their health breakpoint or health value[2] concentration range.[3]

All the eight pollutants may not be monitored at all the locations. The overall AQI is calculated only if data is available for a minimum of three pollutants, of which, one should necessarily be either PM2.5 or PM10. In the absence of data on particulate matter, data is considered insufficient for calculating AQI. A minimum of 16 hours of data is necessary to be able to calculate the concentrations of these pollutants.

The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) air quality monitor displays the individual pollutant-wise sub-index to provide the air-quality status for that pollutant, even if the overall data is insufficient to calculate the AQI. It may not give the complete picture of air pollution and its effects in an area but AQI is the only way we have to measure the air quality in our cities.

Problems with the ‘average’

The average AQI, while being a convenient marker to track the city’s pollution levels, is just that – an average. It glosses over the highest and lowest readings and, therefore, can end up masking or papering over the more polluted areas. While one or two averages a day help keep track of how polluted Mumbai is, what is needed now as air pollution shows little sign of abating are more measuring stations – ideally one or two per civic ward. For example, on February 13, 2023, when Mumbai’s average AQI was 148, there were cleaner areas such as Worli with a remarkably low AQI of around 82 while areas such as Bandra-Kurla Complex showed a reading of 311.

The localised information has then to be relayed to people in meaningful ways on a continuous basis. This allows people to take the steps at their end such as suspending their morning walks and runs, staying indoors, and planning other activities. More stations at more locations across the city will help get a better and granular picture of the exact level of air pollution, going beyond the average readings.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Causes of Mumbai’s poor air

There has been a major rise in the number of bad air days this year compared to the average in the past three years which was 28 days; this year saw 66 days of ‘poor’ and ‘very poor’ air in the winter months, according to Dr Gufran Beig, founder of System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting And Research (SAFAR) who now teaches at Bengaluru’s National Institute of Advanced Studies. He analysed the data for 92 days till February 8, 2023.[4]

The first Air Quality Assessment carried out by National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) and Mumbai Pollution Control Board (MPCB) in 2010[5] was repeated at least a decade later and its findings were presented during a town hall in 2021. It was found that 45.1 per cent of particulate matter came from unpaved road dust and 26.6 per cent of the share was taken by paved road dust in Mumbai. This, in effect, means that road dust contributes to close to 72 per cent of particulate matter in Mumbai. The next highest contributor to particulate matter is construction at eight per cent.[6]

A study by SAFAR found that the transport sector contributed to 30 per cent of Mumbai’s pollution. Biofuel or residential emissions followed second at 20 per cent, industries contribute 18 per cent, and 15 per cent from windblown dust. The rest of the pollution can be attributed to weather-related factors.[7]

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), in its budget for the year 2023-24, identified road and construction dust, traffic congestion, industries, the power sector and waste burning as the major contributors to air pollution.

What the construction rules say

The continuous din of construction is a sound that most Mumbaikars are familiar with. What they also saw for the past two months is the dust that rose from it, covering in thick layers the city’s high-rises, leaves of trees, and literally every surface. Mumbai has been home to a massive and continuous stream of construction and demolition – from metro lines and flyovers to the Coastal Road and massive commercial or residential complexes. The ongoing redevelopment of several buildings adds to the dust.

Besides, the BMC has undertaken infrastructure work which require digging up of roads across the city by its Hydraulic Engineering Department and Storm Water Drains Department. The BMC has laid down rules for its contractors – and for all construction sites – which make it mandatory for them to “adopt environment friendly construction methods and practices so as to cause minimum inconvenience to the public and protect ecological degradation”. To contain air pollution:

- All construction equipment, including the wheels of vehicles, should be washed clean of visible dirt/mud before exiting the construction sites.

- Dust-producing materials should be transported in vehicles fitted with covers.

- The height from which materials are dropped shall be the minimum practical height to limit the generation of dust.

- During dry weather, dust control methods such as water sprinkling ought to be used daily especially on windy, dry days to prevent any dust from blowing and causing nuisance. Contractors are supposed to provide water sprinklers for dust control.

- Dust-generating materials need to be stored in closed containers/bins or in areas that are protected from the wind. During drilling and blasting, water sprays, canvas covers and blast nets need to be used.[8]

In mid-December last year, as part of the steps to bring down air pollution, the BMC directed assistant municipal commissioners of 24 municipal wards to halt all construction and waste disposal work for 10 days, along with asking ward officers to clean dust from roads. It also said that it would sprinkle water on roads in areas where air pollution levels are high. In mid-February, the AQI levels in Mumbai continue to be ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’.

Photo: Imtiyaz Shaikh

It was found that Mumbai Metro construction, which has been in the news for a host of environmental reasons including indiscriminate tree-cutting at Aarey, has also been a major contributor to dust pollution, according to a report by World Resources Institute (WRI). Similarly, a NEERI study commissioned by the MPCB found in 2018 that the work carried out by Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation Limited was exceeding the prescribed standard of noise levels for day and night time. The Bombay High Court, however, allowed them to continue with the work between 10pm and 6am provided they followed the guidelines laid down by NEERI.[9]

The rules set by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and enforced by the MPCB, the execution wing of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change of Maharashtra, have laid down Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Management Rules. It is mandatory to shut internal and approach roads to the site, designate delivery and deposition points for the debris, monitor work zone air quality and also the ambient air quality. The Rules also lay down that debris and transport vehicles should be covered; water sprinklers have to be used at all unloading points and on the roads taken by these transport vehicles; these vehicles be washed only at designated spots and the water reused within the plant for suppression of dust.[10]

The important law

The Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, lays down rules for the prevention, control, and abatement of air pollution through the pollution control boards in states. It gives powers to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) at the national level and the state boards in various states of India. The Act grants the CPCB and state boards the power to declare air pollution areas, impose restrictions to maintain standards for emissions, and consent to setting up of industrial plants. The boards also have the authority to carry out inspections of plants and equipment. Through an amendment in 1987, noise was also included in the list of substances suspended in the air as pollutants which allowed the Act to also regulate noise pollution.

A systemic exploitation of Mumbai’s environment is underway, with the continuous concretisation of the city’s forests and sea shore. With vegetation cover threatened by increasing construction, the trees on land and mangroves in between the land and sea unable to absorb the rising levels of pollution, Mumbai is looking at a grim state of affairs. Rising pollution levels and temperatures in the absence of trees will not only lead to more health problems but also intensify the ill-effects of the increasing Urban Heat Islands.

The air pollution and smog are likely to be followed by a harsh summer — the February temperatures are already way above normal. Initiatives at the personal level do not enhance the collective life of cities. Without a major intervention by all authorities to restore Mumbai’s ecological balance, the future is grim indeed.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover photo: Imtiyaz Shaikh