Nearly 1,500 families residing in Ambedkar Nagar at Cuffe Parade, Mumbai, underwent “physical, mental trauma, financial loss and most importantly their right to shelter” when they were evicted in May 2017, observed the Maharashtra State Human Rights Commission (MSHRC). In its order two years ago, the Commission directed the state government to form a committee and plan the rehabilitation of those displaced.

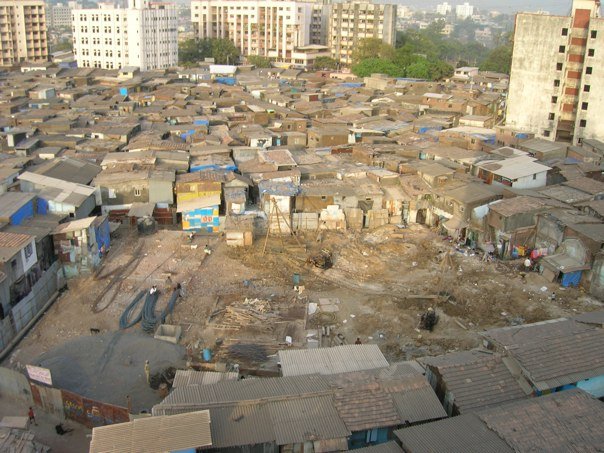

An informal settlement or slum on the city’s edge, Ambedkar Nagar dwellers had encroached upon the mangrove area, claimed the state forest department. It pushed the demolition drive which lasted four days in the punishing summer heat and rendered thousands of families homeless.

Demolitions of informal settlements are not new in Mumbai or in any city of India. What made this case different was the approach to seek justice. In their submission to the MSHRC on behalf of the evicted, activists of the Ghar Bachao Ghar Banao Andolan relied upon the Delhi High Court’s judgment of March 2019 that slum dwellers have the Right to the City.

This judgment has since become a benchmark not only among activists but also urban planners, and lawyers for its clear articulation of the Right to the City (RTTC), a concept and a slogan first introduced by the French sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre in 1968. It encompasses people’s right to belong to a city and make urban spaces, and it also covers the more tactical rights to housing, work, leisure and more in a city.

The international movement around RTTC has been strong but the idea – political in nature – has only been sporadically addressed in India. The Delhi HC brought it centre stage. It should have gathered momentum especially in the Covid-related lockdown of March 2020 which saw millions forced to march out of cities on foot to reach their villages because they could not – or did not want to – live in cities. The jury is out on whether the Delhi HC has proved to be significant in deepening conversations and building movements around RTTC but the consensus is that urban Indians are better off with at least the words on paper.

The all-important ruling came in the case of Shakur Basti, near Madipur Metro station in Delhi. Around 5,000 slum dwellers of the jhuggi jhopri were evicted in December 2015. The informal settlement had come up on railway land, claimed the authorities. Hearing a petition filed by Congress leader Ajay Maken, the bench comprising Justices S Muralidhar and Vibhu Bakhru stated that “…removal of the jhuggis without ensuring their relocation would amount to gross violation of their fundamental rights” and observed that “the Right to the City would be relevant here as an important element in the policy for rehabilitation of the slum dwellers”.

The Delhi HC invoking it has given teeth to urban movements campaigning for rights, especially for housing rights. “It’s a good order. It has become a tool for us while fighting for the homeless and the displaced,” says Bilal Khan of the Ghar Bachao Ghar Banao Andolan who cited it in Mumbai’s Ambedkar Nagar case.

as illegal occupants even if their structures are legal.

Photo: Andrew Wade/ Creative Commons

Housing right recognised, not always upheld

The RTTC was embraced by ‘Cities for All’ policy paper released on the eve of the UN Habitat III and explains it as “the right of all inhabitants present and future, to occupy, use and produce just, inclusive and sustainable cities, defined as a common good essential to the quality of life”. It contextualised what the United Nations Committee for Economic Social and Cultural Rights had laid down about urban settlements of the poor: that they come up because of displacement, poverty, disasters and development projects, and under the human rights law, a government is bound to provide social protection.

The concept, founded in the intrinsic values of human rights, has been invoked time and again in cities around the world but the practical implementation has been a challenge. Alison Brown and Annali Kristiansen in ‘Urban policies and the right to the city: rights, responsibilities and citizenship’ write that “…the Right to the City is a vehicle for urban change, in which all urban dwellers are urban citizens; it creates space in which citizens can define their needs but, in order to appropriate substantive citizenship, citizens must claim rights of participation and allow others the same right. The critical problem is that there is little practical guidance on what the right to the city entails, or how it can influence relations between urban dweller and state.” [1]

In India, courts have often cast informal settlements and citizens without formal housing as “encroachers” or “public nuisance”. However, courts have reiterated the right to housing and the Supreme Court has upheld that the right to adequate housing is interpreted as a fundamental right, emanating from the right to life protected by Article 21 of the Constitution of India. [2] The Delhi HC went a step further and articulated it in the context of the Right to the City.

There have been other verdicts in favour of slum dwellers earlier too, but the Shakur Basti one was specific, progressive and highlighted the rights of every citizen. Mathew Idiculla, a lawyer and researcher on urban issues and a consultant with the Centre for Law and Policy Research, says, “Unlike the Olga Tellis verdict, this evoked the right to the city and gave clear remedies. It said that slum dwellers cannot be forcefully evicted, that too without consultation.”

Despite court orders, the right to housing is usually violated while evicting slum dwellers, who, activists say, are easy targets. Slum dwellers, often seen and treated as illegal occupants even if their structures are legal, tend to be excluded from basic rights. Reports from across the country narrate ruthless evictions which are traumatic for the slum dwellers – many of whom are unaware that they can claim the Right to the City.

In Guwahati, for example, hundreds of residents of Cachal area were forcibly evicted in May during a heavy downpour because the authorities wanted to protect the wetland, Silsako Beel, and make the city flood-free. The residents said they had been living there for 20 years, paying electricity bills and taxes, yet there was no talk of compensation or relocation.

Hundreds of evictions despite judgment

In the Olga Tellis versus Bombay Municipal Corporation case in 1985, the judges had said that the right to livelihood was part of the right to life and held that eviction is also deprivation of means of livelihood for the poor. In the Sudama Singh case of 2010, the Delhi HC said that slum dwellers cannot be evicted without rehabilitation and they also should be consulted on the relocation.

“The Olga Tellis case was a broad judgment. It did not specify how to protect the rights of slum dwellers. The Sudama Singh case was the first major judgment in favour of slum dwellers…Yet the courts have often supported eviction,” says Idiculla, “The judgments in both the Sudama Singh and Shakur Basti cases used the jurisprudence of the South African Constitutional Court, which has given many progressive judgments supporting rights of informal settlement dwellers.”

The Delhi HC judgment is binding in its own court only, but its persuasive value cannot be denied. “It is not binding across India. It can be cited but that doesn’t mean that the other courts are bound to follow it,” says Idiculla. The judgment, however clear on people’s Right to the City and hailed as progressive, did not prevent other evictions especially without consultation and giving prior notices. The Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) documented at least 245 incidents of forced eviction across India during the pandemic from March 2020 to July 2021. [3]

Lawyer and activist Gayatri Singh points to the Khori Gaon eviction and in Mumbai’s Bandra to show that little has changed since the Delhi HC judgment; slum dwellers were given notices of eviction without alternative accommodation. “The argument is that there is no land available to rehabilitate people in Mumbai. Why the double standard because builders manage to acquire land belonging to the government,” she asks.

In 2021, thousands of people protested at Khori Gaon in Faridabad, around 40 kilometres from Delhi, as their houses were bulldozed and nearly a lakh were evicted from the Aravalli Forest land. The SC ordered eviction on the grounds that the informal settlement had encroached on the forest land but directed the Municipal Corporation of Faridabad to rehabilitate those eligible.

Ishita Chatterjee, an architect and PhD scholar at the University of Melbourne who studied the Khori Gaon settlement, points out that the mere existence of court verdicts in favour of people in informal settlements does not guarantee the protection of their rights. “We can hope that (such) court verdicts will impact other cases but, unfortunately, that is often not the case. They are dependent on the bench hearing the cases, state policies and compliance of court orders…The HC judgments in Khori Gaon case in 2016 were exemplary for emphasising social justice and questioned the state authorities, but that was completely ignored by the Supreme Court,” she says.

unaware that they have the right to the city.

Photo: Joe Athialy/ Creative Commons

Implementing the RTTC judgment

The Delhi HC judgment can translate into positive measures if the Supreme Court endorses it, says Idiculla. “If the Supreme Court cites and quotes the Delhi HC judgment, and comes out with a progressive verdict using the same principle, it will have an impact across India. At a political level, if these ideas translate into policy measures, it will give protection to the slum dwellers,” he explains.

The recognition of the Right to the City means that not only do people have a right to housing but also that slum dwellers play a role in the rehabilitation process, and that there is a deliberative democratic process. In both the Sudama Singh and Shakur Basti cases, the court used the term “meaning engagement”. In the evictions since, the authorities have not even engaged, let alone meaningfully, to consult the people or work out a rehabilitation plan.

Shweta Damle, founder of Habitat and Livelihood Welfare Association, says the apathy towards rights of slum dwellers continues. “There is no positive change after such verdicts because everything is linked to the market which has reaped the benefit (of housing policies). Slum formation happens because this is the most affordable place. Slums are vibrant economic hubs, living is subsidised,” she points out.

The rehabilitation or rehousing process can begin with the clear and complete recognition of housing as part of the Right to the City by all stakeholders, but the perspective is lost in the long and cumbersome nature of the process. Even when rehabilitation accommodation is offered to the evicted, the alternative housing is far away from their place of work, point out activists who call for in-situ upgradation.

The existence, or the lack, of documents to prove the claims of slum dwellers becomes an issue here raising questions about whether documents of citizenship become necessary to claim one’s Right to the City. Even if some slum dwellers know their rights, it is not easy for them to go the legal way to fight for their Right to the City to be honoured, especially when basic rehabilitation is itself fraught with harassment from the authorities. “There should be pressure on the government instead to enforce policies and ensure they are implemented,” says Singh.

It’s a long and difficult road ahead.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An associate editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: Creative Commons