For Surat, Patrick Geddes proposed that by very simple measures like planting more trees, cutting a few paths, filling up some unsightly holes, and making a few bridges from bamboos and branches, the “existing nullahs” could be transformed into public parks (Geddes 1965: 15). Young boys and girls could be mobilised as civic volunteers to carry out the same. And all this could be done “not as expensive municipal closure carefully fenced in with barbed wires and bye-laws” but by the youth, young men and women working as civic volunteers. And over time, the planting and watering would give rise to public parks for the benefit of all (ibid. 22).

In Dacca, Geddes found khals, with their many minor tributary nullahs, pools, ditches, and slopes to be an obvious and extreme example of the influence of natural drainage in shaping the original layout of the towns. What led to the deterioration of the khals was that initially people settled as close to the stream as its flood level would allow, and then with the growth of population, new and higher levels would be occupied and gradually, their ends and courses were raised by the accumulation of rubbish disposed of by the people.

New settlements came up on these and so it went on to create problems of sanitation and drainage. Geddes was quite aghast by the discussion among the engineers regarding the improvement of khals, one of the viewpoints expressed was to fill up the 12.5 miles of khals at the cost of Rs 7,50,000, so that 50 acres of land of far lower value could be obtained (Geddes 1917a: 18).

The splendid Dholai Khal, for example, which had fallen into disuse and abuse, in his estimation could be restored by “deepening and cleaning”. He was happy that canalisation of a portion of the khal had been suggested by the government engineer, he only asked for its further extension. Its benefits were immense: The silt obtained from deepening and cleaning could be a rich source of fertiliser, horticulture could be undertaken on the banks, gardens and green spaces could be created and pisciculture could be paid greater attention. But most important, it would be a “park system of the rarest extent and beauty, a water park unparalleled elsewhere, and on which, after the reasonable improvement for which we are pleading, a new recreative life would arise; and this for the University and city alike” (Geddes 1917a: 19).

But all this could be dealt with by planning with consideration and foresight. For example, the riverfront, the best of all the open places of Dacca, which had hitherto been neglected, could well be developed into a “river esplanade”. For that, encroachments would have to be stopped in reality. Bathing ghats could be provided, corners and vacant spaces could be used for trees and shaded areas to sit, and as funds flowed in from official and individual donors, “a new city front, at once useful and beautiful, healthful, recreative and religious alike, would gradually arise” (ibid. 6). And although water sports like boating and sailing were not popular sports, they could also be encouraged.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Repair and renew, with people

Typically, Geddes pointed precisely to the spots where something beneficial could be undertaken, and this was possible only because of the close contact he made with the area he was studying. His detailed comments are noteworthy. Referring to Hagi tank, he writes, it needs a little planting; the cluster of three tanks, presently surrounded by dilapidated and insanitary “bustis”, could be improved without a wholesale eviction and destruction of the hutments. A sketch or a model of the proposed plan could be prepared to show the tanks with rectified roads, lanes and paths, plantation attended to, house rebuilt with simple material of course, but with higher plinth, adequate space, light and ventilation, “in short at once with recovery of the old rural standards of good workmanship with the acceptance of the needs of the town”4 (Geddes 1917a: 14).

Even Lucknow, which had an excellent park system, Geddes found, needed to grade and plant the banks of the nullahs. These were annually being cleared at considerable expense to the municipality which could be greatly reduced, he argued, to one-third or even one half of the present outlays if they were planted. He felt confident that with help and encouragement from the municipality, leaders of the Mohalla Committee, and a plan for improvements prepared by officers of the Town Planning Committee, peoples’ active participation could be mobilised. Boy Scouts, the young citizens, religious leaders, teachers and their students, municipal workers, gardeners, town planning officers, needed to be mobilised in the task of restoration.

In Broach, Geddes identified possible sites for development of a playground, a garden and a market. But, “the greatest surprise and pleasure of our whole visit to Broach opens out as we go on eastward. The Nullah, though neglected, little spoiled, is even beautiful; it needs only planting here and there to make it perfect as a landscape, and a few paths to make it a resort,” Geddes suggested. The varied landscape of the town, which did not pride itself on its beauty and amenities, fascinated Geddes.

Photo: QoC file

Plan with environment, plant trees

It was of utmost importance to Geddes that the natural assets of a town, and everyone had a fair share of it, should be protected, nurtured, respected, and integrated into the design of that city. Every city offered a distinct and varied landscape, each city was different, and each required to be planned with respect to its environment. And where it had suffered and degraded, steps had to be taken to restore it.

Trees occupied a special place in his reports, he emphasised the need to grow trees, plants, shrub, bushes, which would provide shade, clean air, fruit, flower, in other words, health and joy. He had an extensive knowledge of trees, and offered detailed and precise suggestions on which kind of tree/plants best suited the need and condition of a particular site, whether it was the road-side, slopes, banks, poor settlements, parks or private gardens of the rich.5

Geddes’ knowledge of trees and his conviction that tree planting was vital for the health of the city environment is impressive. A large section of the Lucknow report is devoted to his proposal on better maintenance, expansion and improvement of the public spaces which dotted the city: Parks in residential areas, the surrounding temples, mosques and historical monuments like tombs, palaces, and so on. He variously recommended small modification in the layout, or just clearing of rubbish, planting of suitable trees, repair of already existing fountains, creation of better access to the park, addition of flower beds, hedges, shaded seating places, little playgrounds.

He strongly advocated better maintenance of spaces around the scattered tombs which lay neglected but which could be, with little effort and expense, transformed into charming public places. Not just isolated parks but also the houses surrounding it, the adjoining mosque or temple, tank and the roads around, could be slightly redesigned to uplift the entire neighbourhood. In summary, Geddes was suggesting for this “enormous city area” enlargement of spaces and their upgradation into parks including Zenana Parks, gardens, sports, recreation and leisure areas (Geddes 1916: 35–54).

An elaborate and well-argued reply, obviously to those who raised objection to tree planting on several counts, appears in his report on Lucknow. Expenses involved were often put forth as one of the reasons, to which Geddes’ reply was that establishment of a municipal nursery on one of the many vacant cultivable sites could be undertaken without incurring much cost. When the saplings were ready to transplant, teachers and a few pupils could be encouraged, with time more and more could be involved, to assist the Municipal Tree Planting Department.

The introduction of “Arbor Day”, a holiday for tree planting that was already popular in America and Europe, could be done in India. To protect young saplings from goats around, “tree guards” would be necessary, and these could be drawn from schools and neighbourhoods that wanted more shade and beauty in their locality. A little training and a manual would equip them to perform their task effectively. He goes on to argue that since watering the saplings for the first two or three years involves cost, provision of “weep holes” on the adjacent drain whenever possible can be more economical. To those who objected to trees as “dust-catching”, he retorted “Better dust upon leaves than in the lungs of the citizens” (Geddes 1916: 68).

Photo: Md Shaifuzzaman Ayon/ Wikimedia Commons

Native trees (not foreign) and small gardens

Geddes drew attention to the importance of selecting trees appropriate to the place and requirements. He had noticed that closer to the houses, small flowering trees, but in the interiors, trees with heavier foliage were grown. It was evident that, “…the universal popularity of the Neem, as compared with the tamarind for instance, is partly to be explained by the lightest breeze passes readily, as compared with the dense foliage of the other” (ibid. 69).

Geddes raised an issue which has acquired even greater significance in today’s cities of the increasing preference for foreign trees over their indigenous counterparts. While recognising the fact that the Australian Casuarina and Eucalyptus grow fast and with little water, Geddes found them lacking in beauty and shade. Such trees have their uses in a limited way and in other regions, “but in the town I plead that it is far better to confine ourselves to the vast repertory of Indian trees” (ibid. 70). They have no human association with India. He recalled the ludicrous example of Stratford-upon-Avon, the city of Shakespeare’s birth and death where “not a single one of the trees of Shakespeare’s poems or times or associations” had been planted (ibid. 70). One could add innumerable examples of such foolishness from every city in India.

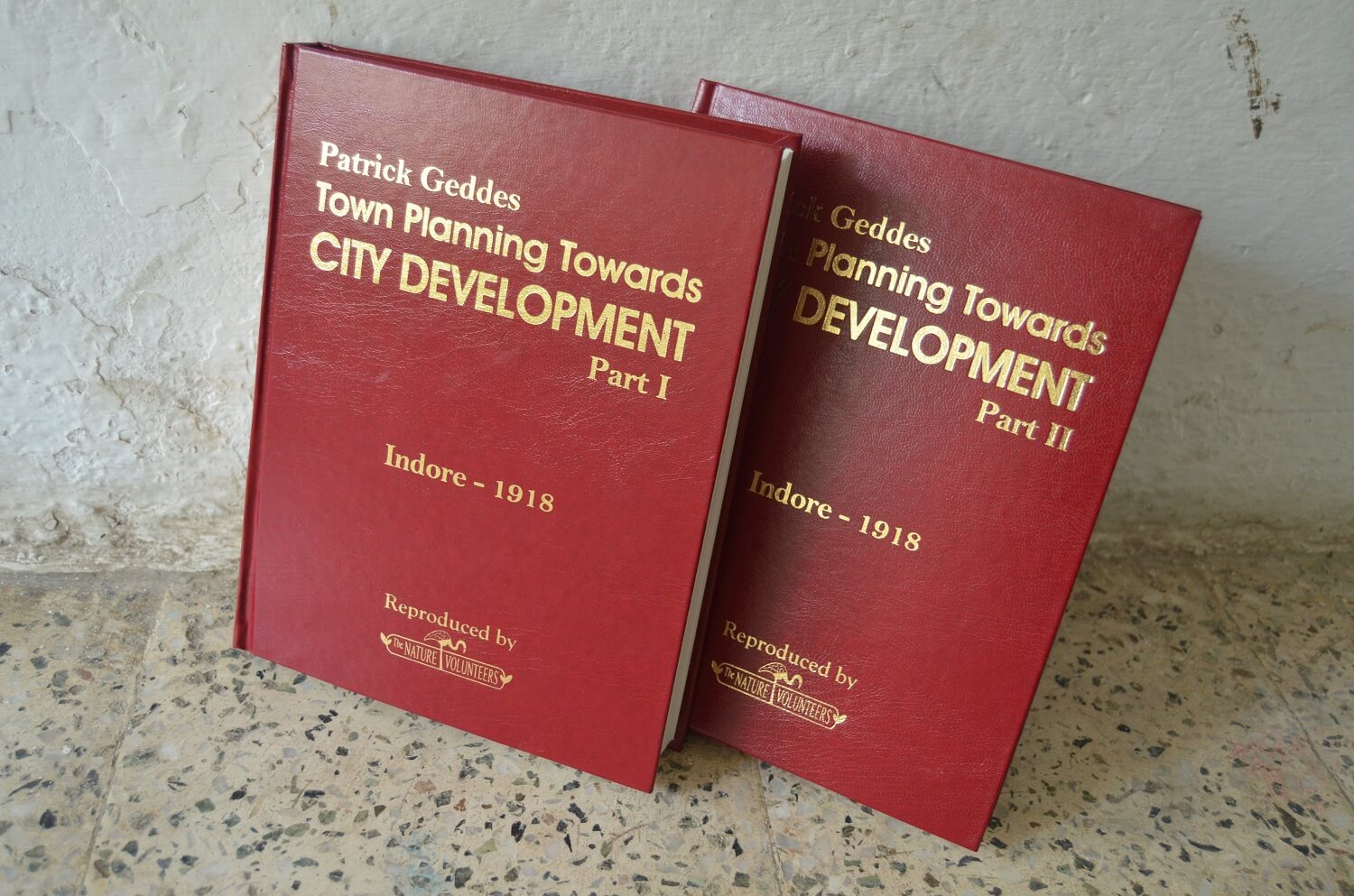

Geddes advocated gardens, many small rather than one big garden, to be developed in every locality, rich or poor, for the health benefits of people. With a little bit of planning, small spaces could be created everywhere for growing vegetables, fruits or for fresh air and additionally for providing an outlet not only for domestic water but for other organic waste matter which otherwise becomes a big problem. Geddes elaborated on this in his Indore report. The cost and effort of watering in the initial years was small compared to the returns. Interestingly, the diversion of domestic and other organic waste matter to water vegetables, fruit trees, is being practised at present by an NGO in Bangladesh6

On the question of open spaces, Geddes noticed that in several cities, large vacant areas, overrun by weeds and bushes, lying waste, only adding to the dust and heat in the atmosphere. They could certainly be cleared, and even on the poorest soil, he suggested, trees like the thorny Acacia could certainly be grown while selected fruits trees could be cultivated on the somewhat richer soil. Geddes was convinced that the non-availability of a healthy diet, fruits and vegetables, was responsible for the prevalence of a number of diseases, especially among women and children.

Not only isolated parks and gardens, Geddes recommended what the American planners and designers termed as “Parkways”. This meant that parks and public gardens which had hitherto been disassociated, like oases, were to be connected. This was to be achieved by connecting park with park by utilising every vacant spot, big or small, for planting trees, plants, shrubs, vegetation of all kinds, so that one park extends to the next in a continuous stretch. This could be tried out in both thinly populated and poor quarters as well as in expensive built-up localities (Geddes 1922: 53). The ecological benefit of the parkways is recognised more and more now.7 For the Kapurthala Palace square he made similar suggestions. A unified scheme of parkway could be undertaken to link gardens, zenana parks with others, to form a continuous open green space, even a zoological park (Geddes 1917c: 10).

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“Nature access” in cities

With the preservation of hills, moorlands, streams, rivers, Geddes believed, must come forestry, sylviculture, arboriculture, park making, and with it again must come “nature-access” to meet the need for physical and mental well-being of the city-dwellers. “Such synoptic vision of Nature, such constructive conservation of its order and beauty towards the health of cities”, Geddes argues in Cities in Evolution, “…is more than engineering: it is a master-art, vaster than that of street planning, it is landscape making; and thus it meets and combines with city designs”. (Stalley 1972: 162).

Accessibility was understandably an important condition for Geddes, with memories of free access he had to the vast countryside in his childhood looming large in his consciousness. It irked him that the city parks in his own country continued to be treated and managed very much like the mansion house parks which they often were, even after the municipalities had taken them over, “…each with its ring fence, jealously keeping it apart from a vulgar world”.

Coincidently, my attention was drawn to an article on Delhi by Anniruddha Ghosal who bemoans the loss of parks, public spaces, and playgrounds there. The parks, he recalls, were the first to go, replaced by malls and apartment houses; public places disappeared one by one and most important existing playgrounds were “beautified”, and flower beds appeared. “Then came the sign boards, banning football, cricket, gambling and drinking”. (Ghosal 2017: 5).

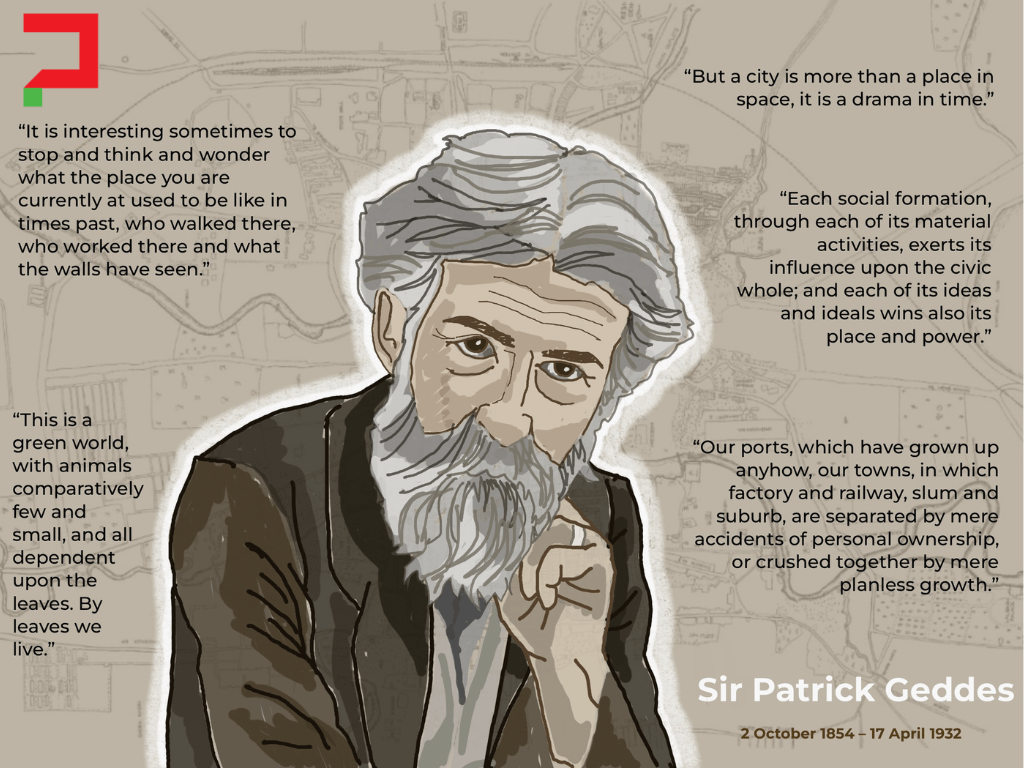

Dr. Indra Munshi, is retired Professor and Head, Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, which was set up by Sir Patrick Geddes as the first Professor and Head in 1919. She is also the executive editor of the Indian Journal of Secularism (IJS) brought out by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS), Mumbai. Her recent book is “Patrick Geddes’ Contribution to Sociology and Urban Planning – Vision of a City” published by Routledge – Taylor & Francis Group. This edited excerpt, with permission, is part of the chapter “Ecological Cities” from it.

Cover illustration: Nikeita Saraf