On December 1, New Delhi was the most polluted city out of 244 cities in India as its Air Quality Index touched 388, according to Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) data. Through the month of November, the city had registered alarming levels of AQI, even tipping beyond the maximum of 500 on the scale. The impact of severely polluted air on people’s health, especially the vulnerable and marginalised, has been documented. However, what flies below the radar is the combined effect of air pollution and heat.

High levels of heat and heat waves lead to physical distress, especially for informal and outdoor workers, as we documented in Delhi in this essay and this. The national uproar about polluted air has made public and official concern about heat waves recede into the background. However, on the ground, in the many bastis and jhuggi-jhopdis that house a large number of informal workers, the combined impact of poor-quality air and heat – even in November and December – is inescapable.

Heat in winter months sounds like an anomaly, yet some areas in Delhi experience it which makes it imperative to have a working Heat Action Plan (HAP). But the plan that Delhi got this year, prepared by the Delhi Disaster Management Authority, does not even recognise such heat spots.[1] In its implementation, phase one or the pre-heat season is listed as January to March, phase two or the heat season from March to July, and phase three or post-heat season from July to September.

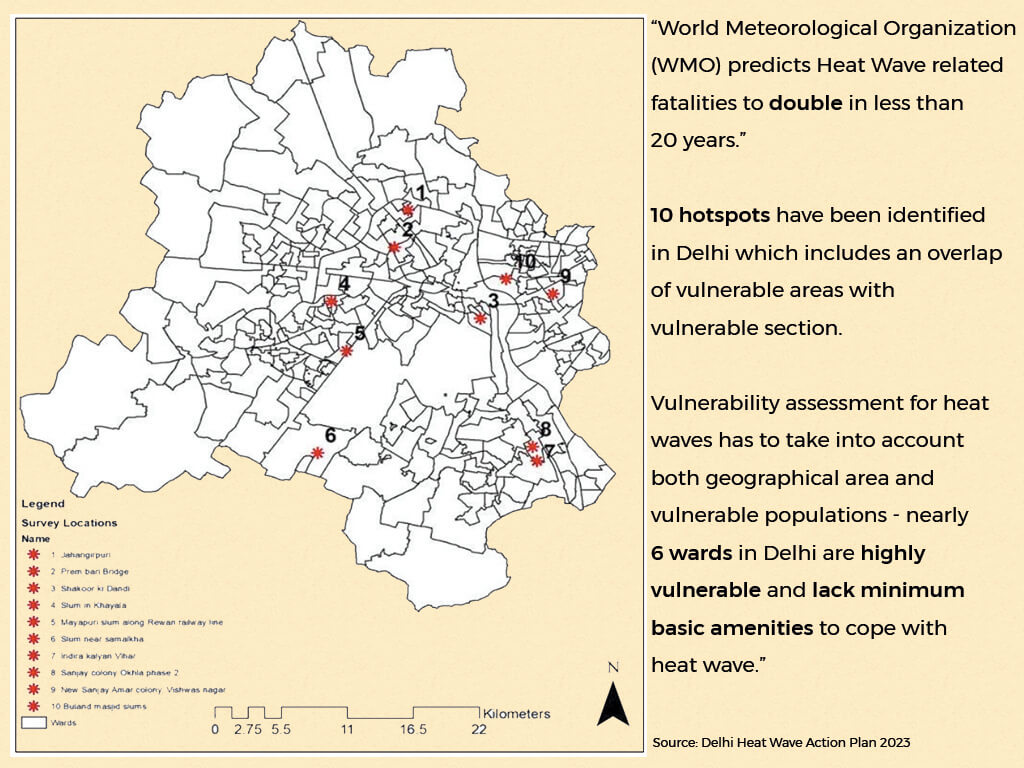

The plan identifies thermal hotspots using data from the LANDSAT 8 satellite and provides a vulnerability analysis across identified wards in the hotspot areas of the city. These areas were arrived at on the basis of a comprehensive index comprising nine sectors – sanitation, water, electricity, health, transportation, housing, cooking, awareness, and heat symptoms – each with sub-sectors.

Photo: Sejal Patel

The cumulative ward-wise analysis shows that approximately six wards in Delhi’s Harkesh Nagar, Khayala, Wazirpur, Bijwasan, Vishwash Nagar and Jahangirpuri have been categorised as highly vulnerable. These wards are found to be deficient in basic amenities for coping with heat waves which points to critical gaps in infrastructure and services. This signifies an urgent need for targeted interventions to improve the resilience of the people here, and mitigate the impact of heat waves.

As part of our study on heat and the city, we conducted field work in Sanjay Colony in South West Delhi. Sanjay Colony is the hotspot in one of the most vulnerable thermal spots — Harkesh Nagar in Okhla Phase II. Sanjay Colony is a highly industrial area, with a population of around 66,820 over an area of 1.99 square kilometres with a population density of 33,414 people per square kilometre. Our study, conducted In November, was to understand the combined impact of polluted air and heat, and document the expectations of residents from the HAP, if they were aware of such a plan.

Sanjay Colony case study

Delhi was experiencing a mild cold spell. Daytime temperatures hovered around a pleasant 27 degrees Celsius. Night temperatures dropped to around 17 degrees Celsius. But, the perennial lingering heat for the residents of Sanjay Colony was felt even in mid-November. The balminess here did not come from bonfires and kitchens, but from the many industries and manufacturing units which surround this low-income residential area. These units, many of which make ready-made clothes, are the source of livelihood for the residents, but they bring ailments too .

Sanjay Colony is one of the ten hotspots identified in the Heatwave Action Plan (HAP) 2023. Kesari Devi, 63, lives in Phase-II of Sanjay Colony. Working as a scrap-picker, she earns about Rs 250 a day. She lives in a makeshift hut on the roadside, protected by only a silver tarpaulin cover which she borrowed from her boss in the Okhla Industrial Area. According to her, clean drinking water is a major issue that the residents face. She lost two of her children to dysentery 20 years ago.

Photo: Sejal Patel

She and others living here are unaware that there is a HAP which places responsibilities on the state government and local administration. This is not surprising; it underscores the need for governments to prepare and execute mass awareness campaigns to inform people of the phenomenon and the preventive or adaptive steps they need to take in consonance with the systems that the government will put in place.

“If a plan is made to counter high heat, please ensure clean and adequate drinking water for us,” said Kesari Devi. The supply of clean and adequate water is the bare minimum requirement for a vulnerable population in intensely dense areas such as Sanjay Colony to tackle heat. Delhi’s HAP acknowledges the issue of water supply in terms of vulnerability and also identifies women in slum clusters as most vulnerable to a heat wave.

Here, people’s makeshift houses are surrounded by the dumping ground. On December 12, Kesari Devi’s hut, along with those of her neighbours, was demolished purportedly to reduce air pollution, but without any notice. “This happens often,” she laments in vain, “We only have to bear the loss.”

Although some cleaning happens, the monsoon season brings the filth into their living areas while the high summer temperatures make the stench unbearable as noxious gases are released from the dump. Another aspect that increases the vulnerability of people to heat waves, which is also acknowledged in the HAP, is the lack of sanitation. The plan underlines the importance of sanitation in vulnerable areas but does not elaborate on short-term or long-term pathways to address the issue.

In the Colony, there are small manufacturing units such as the one operated by Mukesh Kumar Gupta. He makes readymade clothes. Gupta, 40, migrated to the capital 40 years ago and feels that the heat has increased over the years. “This colony is hotter than the surrounding areas,” he said, unknowingly pointing to the Urban Heat Island effect, in which certain parts of a city have higher temperatures than their surrounding areas. “Industries have been expanding and the population too. Many industries here operate without permits,” he added, suggesting a tax on them and calling for people’s participation in making and implementing the HAP.

In the dingy sewing rooms of the stacked building in the colony, we spoke to Harish Gaur. The 42-year-old tailor, who works for 10-12 hours a day, talks about how workers like him cannot even afford to take a day off. Gaur said, “What is a Heat Action Plan if it doesn’t deal with the wages when we fall sick?”

Heat wave and air pollution

This year’s air pollution has made the heat crisis worse in densely-packed areas such as Sanjay Colony. “Pollution, added to heat, damages the lung tissue making it vulnerable to infections and susceptible to an aggravated impact of pathogens. Since heat is harmful to lungs, the combined effect of heat and pollution may be higher in summer,” said Rajeev Sadanandan, CEO, Health System Transformation Platform.

During our field visits, we found that kidney-related ailments were common among rickshaw pullers, construction workers, and daily wage labourers. The impact of heat waves, as an outcome of climate change, on non-communicable diseases and the mental health of the working class is not yet well recognised in India but international studies point to red flags. Prolonged exposure to heat, heavy physical exertion and resulting dehydration, which is routine for daily wage workers, can have a serious impact on the kidneys. When combined with the effect of polluted air on the lungs and other systems, it can mean a spell of ailments for people who can least afford treatment.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is exacerbated by increased and extended episodes of air pollution. The risk of dying from pulmonary disease increases by 1.8–8.2 percent during a heat wave,[2] according to this study. The Delhi HAP does not even recognise the cumulative health impact of air pollution and a heat wave. While there has been discourse around the impact of the Urban Heat Island effect in the increased intensity of heat waves in congested and concretised urban spaces, there is hardly a reference to UHI’s role in increasing air pollution.[3] The UHI caps dust and other particulates at a low level in the atmosphere which results in a ‘Pollution Dome’.

Air pollution and Urban Heat Islands are usually affected by both natural and human factors.[4] (Clinton and Gong, 2013, Li et al., 2017, Ma et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2021). Delhi, as a city grappling with both, is stuck in a cynical cycle of extreme health hazards. As Sadanandan explained, “It is now known that the fine dust particles can even enter the foetus through the placenta. A person who is carried in, delivered, and grows up in Delhi is likely to have lung issues early in life, which will be carried through life. This will be further exacerbated through heat, leading to morbidity which creates a vicious cycle of ailments.”

The question also arises about the adequacy of Delhi’s health infrastructure to tackle these climate hazards. According to a report by World Health Organization (WHO),[5] hospitalisation rates will go up by 8 percent for every 1 percent increase in temperature above 29 degrees Celsius. There are concerns about the adequacy and accessibility of the existing health infrastructure for all of Delhi’s residents because public health facilities are overcrowded and inadequate, which forces the poor to access private healthcare which, in Delhi, is one of the highest priced.

Our field work and interviews confirmed this. The poor were paying exorbitant amounts of money for medical needs in private hospitals and clinics. The NSS health survey[6] for 2017-18 highlighted a significant contrast in hospitalisation costs between private and public hospitals. On an average, the expenses per hospitalisation case in private hospitals amounted to ₹31,845—seven times higher than in public ones. This substantial difference underscores the considerable financial strain faced by those seeking private healthcare.

Photo: Kapil Kajal

Heat and community studies

The government will have to address the combined effect in the HAP – with people’s involvement. ‘Heatwave planning: community involvement in co-producing resilience’,[7] a study on increasing community engagement in policy making in the UK, states that “community entities emerge as distinct powerhouses…standing in stark contrast to the top-down governmental approach.” Policy documents underscore the significance of community and voluntary sectors, perceiving them as locally-trusted agents to reach and aid vulnerable or ‘hard-to-reach’ demographics, DECC, 2014.[8]

Aiken, 2015,[9] posits that community-driven endeavours are often conducive to social and technological innovation and experimentation. Projects rooted in communities, especially within the ambit of energy, sustainability, and food, frequently accentuate self-sufficiency as a cornerstone, leading to a sense of empowerment, Firth, Maye, & Pearson, 2011;[10] Rezaei & Dowlatabadi, 2015.[11] This has significant implications for resilience on various fronts.

The portrayal of communities as organic and agile entities in policy landscapes underscores their pivotal role. The recognition of their credibility, ability to tap into nuanced community needs, and role in fostering self-sufficiency augment societal resilience. Moreover, the synergy between community initiatives and place-based identity emphasises the importance of a collective ethos.

Localise the HAP

The report[12] by the Centre for Policy Research found that the documentation of heat-related deaths in India presents a significant challenge, which casts a shadow over the efficacy of HAPs. India, like other countries, struggles with the categorisation of heat-related deaths due to their complexity. Doctors find it challenging to classify them, especially when comorbidities are involved, often leading to these deaths being attributed to other causes and skewing the statistics.

Official estimates from the National Disaster Management Authority suggest a staggering 26,000 heat-related deaths between 1990 and 2020. However, this figure might not encompass the full scope of heat-induced fatalities, given the challenges of documenting such cases. Ailments and deaths from air pollution are relatively better established. But without clear heat morbidities and fatalities, the combined impact is difficult to establish and, therefore, address in the HAP.

To establish a more accurate count of heat-related deaths, experts suggest conducting excess mortality studies akin to the ones done during the COVID-19 pandemic. This process demands meticulousness and resources, and must be undertaken area by area in the city. Collaboration between various departments of a government, and between governments, is needed; so is a standardised approach rooted in scientific rigour. Only then can Delhi aspire to generate reliable data on heat-related deaths – a crucial step towards formulating effective and targeted HAP.

Asher Ghertner, interdisciplinary geographer, advocates shifting the narrative towards a systemic examination of environmental issues. “When dhobis washing clothes in the open or waste workers clearing trash from planned neighbourhoods were criminalised as ‘the polluting poor,’ but people running diesel generators for fully air-conditioned or air-purified estates were celebrated as ‘citizens’, the collective crisis fundamentally linking the rising fossil fuel burning to environmental impact becomes difficult to tackle,” he explained.

Though Delhi’s HAP mentions civic services like water and housing, the action was missing as we noticed during our field visits and interviews. Area-wise holistic risk assessment studies and abatement plans should become part of the HAP. It is crucial to integrate both short-term and long-term solutions into comprehensive action plans.

The lessons from Delhi HAP, on this aspect, is a way forward for other cities too and highlights the need to shift from enclosure-based solutions to more sustainable and equitable approaches. Revisiting mixed neighbourhood models and favouring more inclusive urban designs are possible steps. A reimagination of the urban landscape based on equitable access to clean environments becomes imperative.

In the recent Lok Sabha sessions, several parliamentarians voiced grave concerns about the country’s preparedness for heat waves and asked whether there are plans to notify heat waves as a disaster to get funding from the National and State Disaster Management Funds. In response, the Ministry of Earth Sciences acknowledged the rise in temperature but asserted that there are no plans to designate heat waves as a natural disaster as this requires “a special request” from the state.

This is not enough. “The government must ensure that a HAP is sufficiently funded and targeted at the worst-affected people,” said Amruta S., Climate Campaigner at Greenpeace India.

What is imperative is to combine Delhi’s HAP and air pollution management. This necessitates a paradigm shift to anchor policies in a holistic approach which considers localised vulnerabilities, community involvement, and inclusive urban planning. This means a departure from prioritising individualised responses towards collective, community-centred solutions which address the root causes of air pollution and heat-related health risks. Only this approach can take Delhi’s poor towards a healthy and sustainable future.

Hrushikesh Patil is a Maharashtra-based independent journalist and environmental lawyer interested in covering the impact of Climate Change-induced disasters on vulnerable communities. Currently working with the Goa Foundation as lawyer and researcher, he is also a member of the environmental communications and advocacy volunteer collective called ‘Let India Breathe’ and is a recipient of many awards.

Sejal Patel, an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker currently working from Delhi, keeps a strong research focus on rural communities and data journalism, as well as the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to the fields. Patel holds a postgraduate degree in Convergent Journalism from AJ Kidwai Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia. Through her work, she aims to challenge established norms, foster social justice, and instigate transformative change.

This is the third essay in a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia. The first essay focussed on the climate vulnerabilities of people owing to evictions for G20; and the second highlighted how climate events impacts Delhi’s informal workers the most.

Cover photo: Sanjay Colony, Delhi. Credit: Google Street View.