“Any city, however small, is in fact divided into two. One the city of the poor, the other of the rich. These are at war with one another.”

This comes from the path-breaking work, The Republic, by the Socratic scholar Plato around 375 BC and concerns justice, order, and character of the just city-state. Plato’s words should find a place in old history books but these, like some of his other observations, resonate in our present too.

The urban local body elections, we are constantly reminded, are about ‘development’ in our cities and the party or parties that bag the majority in a municipal corporation gets people’s mandate to carry out this development. And, so the juggernaut of development gathers momentum, its popular narrative strengthened by election campaigns and statements of key leaders. Its meaning has been mangled to fit the neoliberal perspective which largely means building more and turning over public property – especially land – to private entities, and focusing on a few select showcase areas in the city that are aggressively marketed as the outcome of ‘development’.

In the process, of course, the city is divided into two – one for the ultra-rich and the other for everyone else. Plato’s words still ring true.

This pattern of the ‘development’ narrative dominating urban local body elections was discernible, to those who read between the lines, in the recently concluded elections to 29 municipal corporations across Maharashtra, most notably in the politically significantly heavyweight like the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation but also in the municipal corporations of Navi Mumbai, Thane, Pune, Nashik, and smaller cities like Kalyan-Dombivli and Vasai-Virar in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR).

All political parties wooed voters repeating this narrative of development in their campaigns, advertised the big-ticket infrastructure projects they had built or planned, showed fantastical dreams of a gleaming city packed with modern transport networks and glass-fronted high-rises in gated complexes with a massive central park somewhere, and joyous middle or upper-middle class families partaking it all. No one did it more aggressively or efficiently than the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which has made this version of development all its own. Its ally, the Shiv Sena led by Eknath Shinde, attempted to compete but fared a poor second.

Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis credited ‘development’ for the BJP, bagging the majority in 25 of the 29 municipal bodies. “We faced these elections with a vision of development under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi… That is why we got a record-breaking mandate,” he asserted and, for good measure, added that “we cannot differentiate Hindutva from development”[1]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This dangerous fusion of capital-intensive private-profit-oriented city-making with a toxic expression of majoritarianism is not new but noteworthy. Other leaders like the Speaker of the Maharashtra Assembly, Rahul Narvekar, too emphasised the role of ‘development’ in the elections and the fact that the people’s mandate for the BJP now symbolised “…the desire of Mumbai’s people for the city development.”[2]

Whether its development narrative propelled its success or other factors such as election management did, the reality is that the BJP bagged 89 of the 227 seats in the BMC – not much better than 82 seats in the last election in 2017 but emerging as the single largest party and prepared to preside over Mumbai with Shiv Sena. We can ponder how different this will be from the (undivided) Shiv Sena-BJP combine which governed the BMC for nearly 30 years but it will be an academic exercise. We can ask if all the ‘development’ in Mumbai since 2022, when the Maharashtra government administered the BMC after the elected body’s term expired, had the people’s mandate but it would be futile.

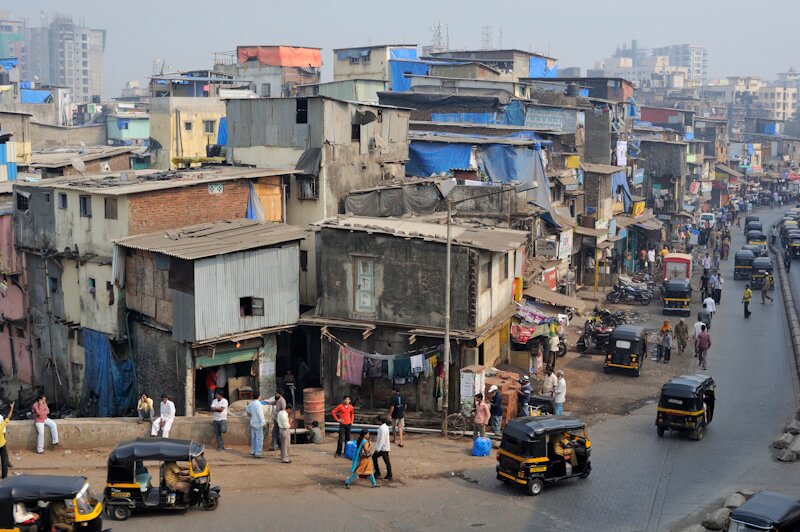

What has prevailed above all noise and news is that the development juggernaut is now in full flow in almost all cities of Maharashtra, most importantly in Mumbai. But what is this development, indeed? What is its nature, what are its impacts on the ecology in the city? Who or which sections of the populations benefit the most, if not exclusively, because development does not mean the same for all of Mumbai’s 18 million? In the marginalised M-East ward, among the poorest part of the city, it means reliable and safe community toilets; in the tonier parts of south Mumbai or Juhu-Bandra, it means the seamless coastal road.

The limited framework of development

The classical understanding of urban development is the deliberate transformation of land and space to improve living conditions for the majority, make accessible health and education facilities, ease mobility for people and goods, enable social and cultural connections while ensuring the protection of natural areas. In the narrative of development now in play, development has been reduced to buildings and more buildings, exclusive enclaves for those who can afford them, mega road projects to move private vehicles furiously fast, and fancy passion projects like the proposed central park or Mumbai Eye.

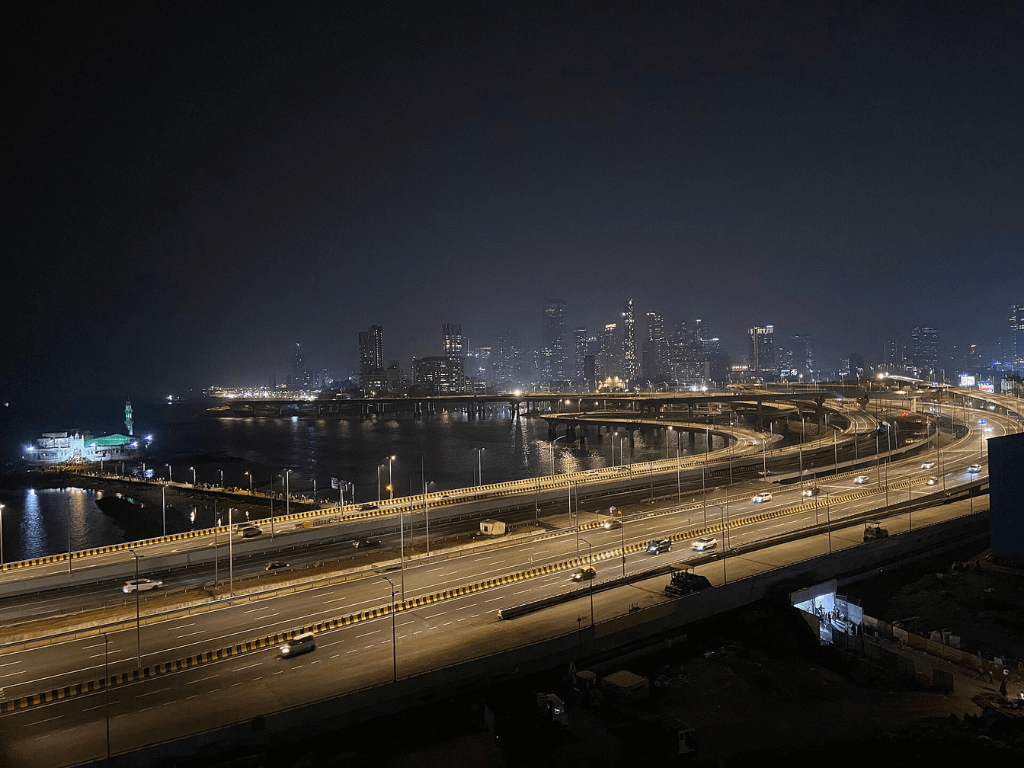

In the past few years, this brand of development has given us massive, mega-crore physical infrastructure projects that largely serve the selected specialised class – the coastal road and the trans-harbour link in Mumbai; the twin tunnel through forested areas and the Thane-Ghodbunder elevated road in Thane; the Ring Road, Purandar greenfield airport, and Mula-Mutha riverfront in Pune, the dream of creating a ‘Third Mumbai’. Then, there’s the redevelopment of old buildings and slums on virtually every street. In a nutshell, this is the limited interpretation and implementation of development.

Photo: Pexels

In Mumbai alone, redevelopment projects worth Rs 18,000 crore reportedly got off the ground in just six months of 2025, taking the total worth of housing redevelopment projects to Rs 1.3 lakh crore. The transport infrastructure boom connecting the city to the larger Mumbai Metropolitan Region, and projects within other cities of MMR like Thane and Panvel, reportedly has Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) signed worth a staggering Rs 3.5 lakh crore.[3] A ‘Third Mumbai’ is being constructed from scratch as a greenfield project in the MMR which carries MoUs of over Rs 4 lakh crore.

The figures are head-spinning, the projects marketed as unprecedented, and the excitement palpable in the corridors of power and those who buy into this narrative of development. However, this is a reductive and exclusionary version of development that blithely ignores comparable social and cultural infrastructure, that cares not a whit about spatial and services equity in a city, that turns most of the city’s residents – except a specialised few thousand perhaps – into cogs that run its economic engine.

It could be the harried and sweaty middle-class worker running to catch the local train at Mulund to reach south Mumbai or the well-off trader comfortable in her car that takes over two hours to negotiate roughly 20 kilometres from Goregaon to Worli – they are both breathing in increasingly toxic air across Mumbai, they are both severely affected by the monsoon flooding and extreme heat. And the same goes for their families. For the millions of marginalised, at the bottom of the pyramid, every bit of this is intensified – extreme heat means their livelihoods are impacted, flooding takes away their homes, air pollution sends them to unaffordable doctors.

How, indeed, has the ‘development’ helped them live a better life? When development is reduced, deliberately and continuously, to physical construction and projects, that too meant for a select few, what does it deliver to the millions in the city and is it even urban development in the true sense? If the answer is difficult, then why did people give their mandate for more of this reductive and exclusionary version?

Even the World Bank, the world’s largest multi-lateral financier cast in pure capitalism, understands urban development as safe and adequate housing that’s affordable, and resilient low-carbon infrastructure accessible to all. Its documents invoke the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable and state that urban development is about “fostering inclusive, resilient, low-carbon, productive, and livable cities”.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The cost of this development

This version of development comes at a cost to nature and people, hiding its true and complete cost. As the environmental economist Dr Pavan Sukhdev remarked at a conference in Mumbai: “nature does not send us an invoice” but millions of the majority are paying the cost.

In only a few months of 2025, the BMC and the state government okayed a plan to slash nearly 46,000 mangroves for the coastal road extension to Bhayander, gifted away 256 acres of salt pan lands – an essential element in Mumbai’s coastal ecology – for the Dharavi redevelopment project, and released a draft plan for commercial exploitation and construction in the eco-sensitive buffer zone of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. In the past two years, building norms were changed to allow builders – Mumbai’s most powerful lobby – to construct on every inch of a plot without leaving any area for trees around a building. Hundreds or thousands of trees are hacked every year.

The story in Thane and Pune is no different. Pune’s environmental warriors have been fighting against a road cutting into the hillocks at Vetal Tekdi as well as mounting resistance against the Mula-Mutha riverfront development which endangers river ecology.[4] Thane lost over 1,200 trees every year in the past few years for one project or another. Its lakes, once in abundance, have been shrinking in size and numbers as the construction frenzy holds away over the city.

Near Nashik, over 1,700 trees spread over hundreds of acres were to be chopped – with the government’s permission – to construct ‘Sadhugram’ for the Maha Kumbh next year.[5] After citizens took the issue to the National Green Tribunal, the tree-cutting was stayed but the threat is not over.[6] In Panvel, once an idyllic town, rapid urbanisation and proximity to the Navi Mumbai International Airport has intensified air and water pollution, deforested mangroves, disrupted the coastal ecosystem, leading to loss of habitat for marine life and birds. “Increasing population, urbanisation and industrialisation resulting in the depletion of natural resources like water and biodiversity” are the main drivers, flagged off the Environmental Status Report 2024-25 of the Panvel Municipal Corporation itself.[7]

The question, therefore, is inescapable: If this version of development is hurting nature and not helping the majority of people, then what is its purpose? The answer is blowing in Mumbai’s sea breeze and smells ‘profits’.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The myth of people’s mandate for this development

That this version of development has people’s mandate is hard to believe but it evidently does. In fact, the majority or the masses are paying the price for it – in public land gifted away, in declining quality of everyday life, in the increasing burden on the public exchequer and so on.

Take Mumbai’s coastal road in the Arabian Sea as an example. Its ecological cost includes enormous land-filling or reclamation of land to the tune of around 275 acres, a project that the UN-IPCC termed “maladaptive” from the climate change perspective. But the nearly 30 kilometres expressway, mainly for private cars, will cost the BMC a whopping Rs 35,000 crore from south Mumbai to Bhayander. Public funds, exclusive private use. How does this constitute as ‘development of Mumbai’?

Similarly, acres of land across the city – from salt pans to the eastern waterfront – are being gifted away to private entities for construction of various projects; if not leased outright, then on the basis of the questionable public-private-partnership in which the ‘public’ seems to increasingly recede or play a minor role. This, in the guise of development, is shrinkage of public property and funds – without consent. If the true nature of development – its complete costs and impacts – were made known to people, would they have given their mandate for more of it?

As development becomes more reductive and exclusionary, people’s relationship with the city space itself begins to fray, even snap. Jonathan Raban, the late British award-winning travel writer, playwright and critic, noted in his genre-bending work The Freedom of the City about the people-city relationship: “We need – more urgently than architectural utopias and ingenious traffic disposal systems – to comprehend the nature of the citizenship, to make serious imaginative assessment of that special relationship between the self and the city; its unique plasticity, its privacy and freedom.”

Raban cast the city as “theatre of the self,” a place where individuals curate their public personas, a “soft landscape” shaped by the people who live in it rather than a hard, unchanging structure, foisted upon them. But development, sold as the ultimate urban dream wrapped in a neoliberal miasma, is the “hard structure” in our cities. No election in India’s democratic architecture brings out the relationship between people and the city as the urban local body elections do – they are intimate, grounded, closely-contested, and impact people’s everyday life. Yet, across Mumbai and other cities that elected local bodies, the local was relegated or forgotten as the over-powering development narrative – set from the state headquarters – held sway.

Cover Photo: Pexels