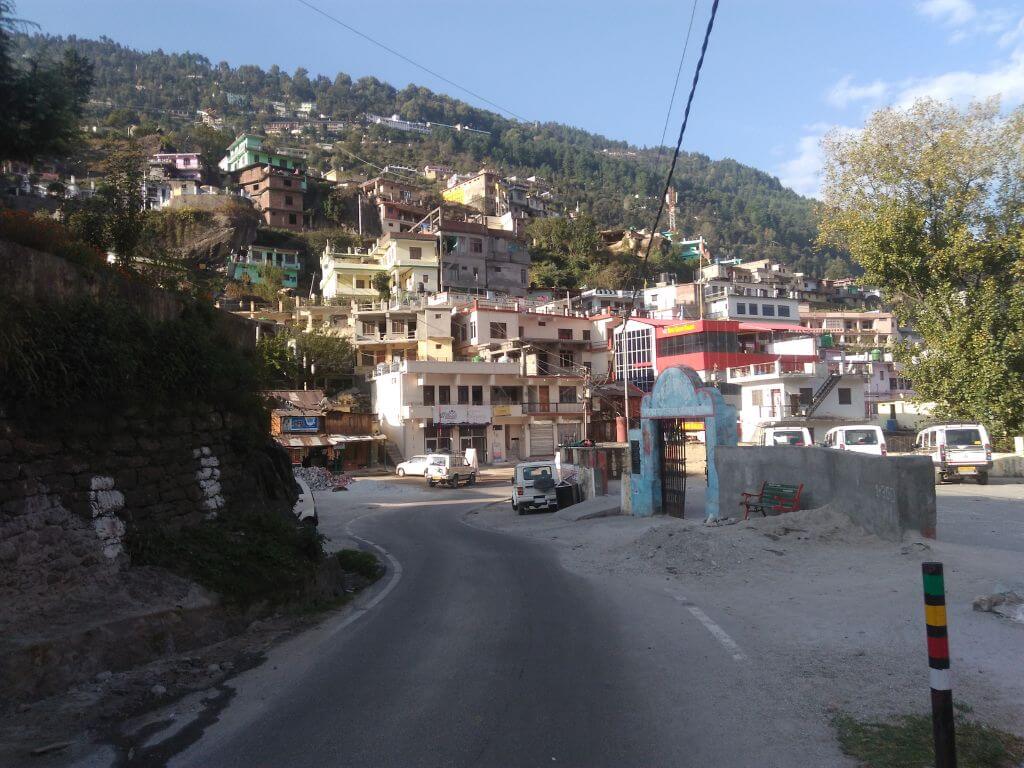

The Joshimath land subsidence through last year, rapidly sinking more than five centimetres in barely 12 days in December 2022 – January 2023, was a disaster waiting to happen. The hill town built on landslide debris does not have adequate load-bearing capacity. Although this was a known fact, unplanned development continued rampantly. Joshimath sits near a major fault zone, which makes it highly vulnerable to sinking because of tectonic activity.

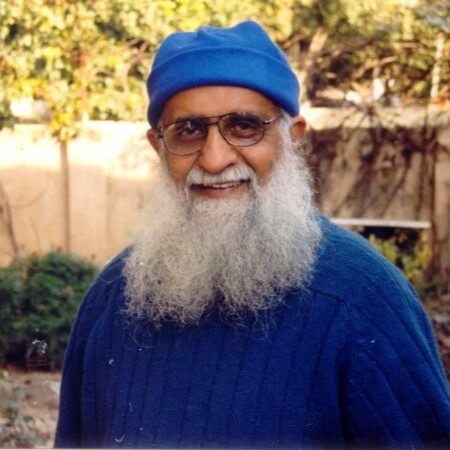

Veteran environmentalist Ravi Chopra is one of the prominent voices against building hydropower projects in paraglacial zones. A Supreme Court ordered committee on hydropower projects in Uttarakhand headed by Chopra had recommended in 2013-14 that no dams in the fragile paraglacial region. Such projects should have been cancelled and none of the dams on the Dhauliganga and the Rishiganga, upstream of Joshimath, should have been built but the recommendation was ignored, he says.

Last year, Chopra quit as chairperson and member of the high-powered committee on the Char Dham Project, terming the project “an assault on the Himalayas”. Question of Cities speaks to Chopra, former director of the People’s Science Institute (PSI) at Dehradun.

The Joshimath land subsidence has raised several questions about sustainably building or expanding towns. What is your perception of the so-called development projects in such hill towns?

Most of the so-called development projects are essentially infrastructure development projects. We are now witnessing rapid urbanisation in extremely sensitive places such as Kedarnath and Badrinath. We are familiar with the fact that the Himalayas are young and fragile mountain ranges and they have a number of major fault zones — these are weak zones where the underlying rock is highly raptured. We have seen at many locations of projects where the kind of careful prior geological drive investigation that needs to be done, isn’t done. Such neglect in infrastructure projects later leads to disasters like the Joshimath crisis.

News reports and scientific literature have pointed out that towns such as Mussoorie, Nainital, Bhatwari and Uttarkashi are threatened by a combination of factors such as soil creep along the slopes. It’s a slow movement of the landmass. A combination of ecological factors like steep slopes, high rainfall, deforestation have worsened the vulnerability in these areas. But locational advantages and governance subsumed by economic growth dreams continue to promote rapid urbanisation and expansion of the built-up areas in these unsafe locations.

The narrative of ‘development’ is usually positioned as economy versus environment though, in the long run, without environmental security even the economy would be adversely affected. What should be the balanced approach to city building?

A balanced approach will first require determining the carrying capacity of the location. Four major factors that have to be considered are the local geology, the ecology, the various sensitive species that need to survive, and the conditions they require. Some of the important factors that need to considered when determining the carrying capacity are the geography of the location — whether it is a valley or a slope like Joshimath prone to landslides — and the cultural significance of the place. Ultimately, the local environment and natural resources have to be respected. You cannot go out and say ‘We are going to build a large city here and so, we will deforest this area’.

Limit the population through uniform development of the region, not just specific locations. For example, the rural areas need to be better developed, giving more attention to agriculture which is the main employment of the local people. The resources which promote good agriculture are forests and water.

If there are better schools and better health facilities in the rural areas, migration to the urban areas would reduce. This is a permanent population migration that needs to be restricted and so we need to revive springs, and reforest a lot of areas. We need to enhance investment in agriculture.

The floating population has to be regulated by spreading the tourists over hundreds of locations. Why should everybody have to go to the Char Dhams, Nainital, Mussoorie, Corbett, and Haridwar? This is where the tourist population comes, but there are hundreds of other locations which also need to be promoted by avoiding the mistakes we have made in these places.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Nature-led planning is the need of the hour. Why don’t we have a default approach towards nature-led planning from governments?

Governments are driven by a five-year horizon of decision-making. So there is a nexus between political masters, who have a very limited time horizon, bureaucrats who don’t want to apply their minds, and huge contractors’ lobbies.

None of these three entities — political masters, bureaucrats, contractors — have enough understanding of mountain ecosystems to respect the constraints that the mountain ecosystem imposes on economic growth. And that’s why the default approach is to go on building, building and more building. What we also find is the collapse of the institutions that were painstakingly created. The Town and Country planning offices prepare 20-year masterplans. It takes about 8 to 10 years to approve a masterplan. By the time it is approved, it has already become irrelevant. And then it is basically shelved or ignored.

Although many committees were formed to study the ecological threat to the Himalayan towns, why did the Joshimath disaster happen?

Why are committee reports prepared and who asked for them in the first place? They are prepared to manage some local political pressure. Or it might be a community protest. If people complain to the National Green Tribunal or to courts, the government has to follow the court orders. The committees are not instituted with any kind of forethought and they prepare reports that are generally ignored.

In 2017, the government of Uttarakhand commissioned a disaster risk study for the state. It got some foreign experts to come and prepare a report. The report was done but what did the government do with it? Nothing. The final report in 2020 identified Joshimath as a hotspot. Did anything change? No. We have the state Climate Change Action Plan. Is anybody even reading the state action plan? No.

You can order committees to make reports but who is going to implement them? The same bureaucracy and they look to their political masters. Finally, something like the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) doesn’t mean much anymore because the monitoring system has been thoroughly weakened, the rules are relaxed. So, even though committees are formed, the threats still exist.

Committees will not be able to solve this, there has to be public pressure. The public pressure in the case of Joshimath – people have been sitting in protest for 100 days — roughly 150 to 200 people came for the sit-in but the government seems immobile.

The middle and well-to-do classes of India number almost 500 million and, it seems, the government is more focused on them. The rest of us can be bought. Recently, I was speaking to some villagers and I said, “You all complain about things not happening or things going wrong, but you still go back to your old ways of voting.” Their answer was very fascinating. They said, “Sir, what will we do thinking about this? Whoever we vote for, the other party buys them. So, at the end whoever gives us money, we will just vote for them.”

Other places in Uttarakhand such as Gopeshwar are facing the same threat as Joshimath. Have there been any warnings for these towns and what has been done?

As I said, there is a disaster risk reduction report which was finalised in 2020. It has listed the hotspots in the state. It’s with the government. Nainital is one example. There’s limited space as you go up a mountain, so the population expansion takes place on the lower slopes. If you read the scientific literature of the past 10 years, you will find warnings for Bhatwari, a town between Uttarkashi and Gangotri, where there has been an attempt to develop it. The technical reports are there, but the mountain is slowly creeping downwards. The Bhagirathi River is cutting the toe of the slope and as the river cuts more of that slope, then the upper portion will not be stable.

According to published reports, Dharchula on the banks of the Kaliganga river, the Indo-Nepal border in Uttarakhand, faces a Joshimath type of situation. That reminds me of Srinagar. A part of the upper slope of Srinagar, which is a University Town, has expanded very rapidly. It is sort of midway between Haridwar and Badrinath, so it sees a lot of traffic.

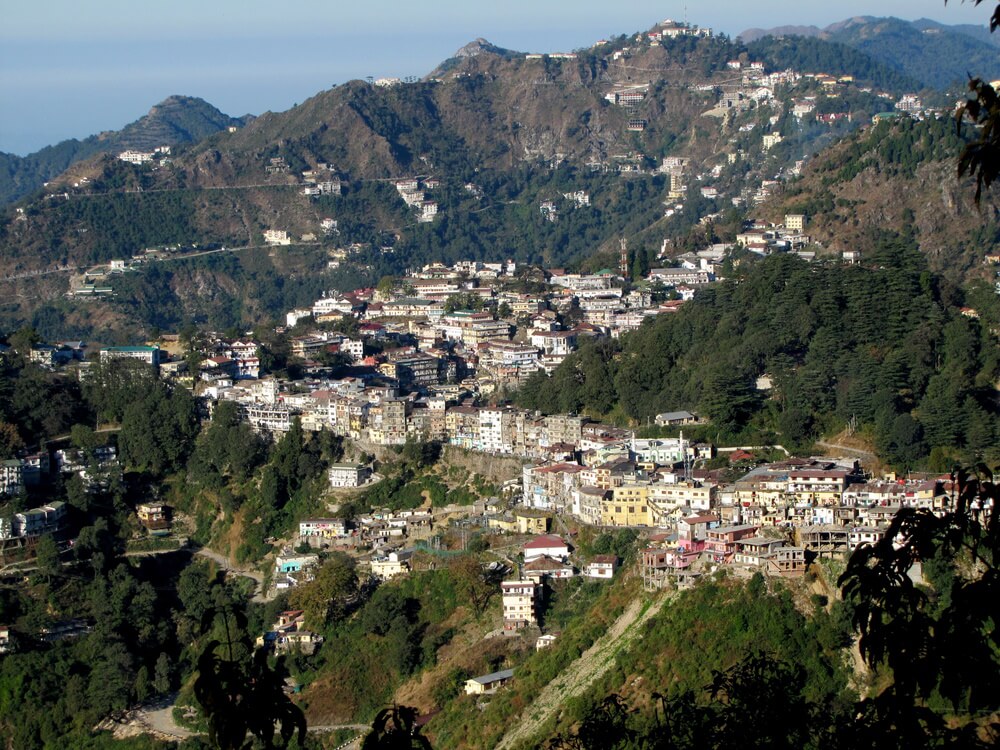

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Is the problem in Mussoorie different from places like Gopeshwar?

In some ways, it is also similar, in the sense that Mussoorie lies on top of a mountain made up of a lot of weak fractured and disjointed rocks. The slopes are made up of debris that comes down every year in some part or the other during the rainy season, when small landslides take place. Because the land in the upper part is limited, newer constructions are taking place lower down. In this sense, it is similar to what is happening in Joshimath or Gopeshwar.

Joshimath is sitting on a huge pile of debris that came down once upon a time in the geological past. And being mainly soil, it’s like a sponge, it gets filled with water and water tends to accumulate. The water accumulation problem in Mussoorie is of a different kind, so the problem is slightly different.

So what are the far-reaching impacts of land subsidence on the environment?

There is landsliding during subsidence. There are more landslides than land subsidence as we don’t have enough forest and green cover. We need to preserve as much of the forest and green cover in the mountain areas as possible. Forest and green cover are required to absorb the CO2 that we are generating.

Moreover, there are all kinds of species in the mountain area. Some very rare species are found only in limited pockets. For example, you can’t find snow leopards at elevations of much below 6,000 feet; the snow leopard, the blue sheep, are varieties of the species you don’t find lower down. Floral species too are determined by the elevation.

If a huge portion of a slope slides into a river, the massive amount of solid matter can form a dam. As water collects behind the dam, the pressure builds up and since this is not an engineered dam, such natural dams often rupture. This happened in 1970 when the amount of sediment that came down small Birahi Ganga and then the Alaknanda was so huge that the Upper Ganga canal, which begins in Haridwar, was blocked with sediments for 10 kilometres. The farmers lost one full irrigation season. In 1978, a landslide in a small mountain stream took place in the upper Bhagirathi valley. The barrier broke and the flood came rushing down the Bhagirathi. Such catastrophic failures also have to be guarded against.

Are there any other steps which need to be taken to reduce the threat to places like Gopeshwar, Mussoorie and Nainital?

The reports are lying with the government and but it does not seem that they will be implemented in the near future. One can argue, ‘Joshimath is too recent. Give it another year or so and you will start seeing a different approach’. We will wait but I personally don’t have much confidence that the present system of governance can deliver the kind of careful infrastructure development that the mountains require.

What is the way forward, especially for Joshimath and the other surrounding areas?

For Joshimath, the suggestion was to begin with a serious carrying capacity study. Do the carrying capacity study and then identify the weak areas where the land (soil) is going to continue to slide. Mark out the areas for no construction, areas where there can be only light construction and areas that they can have heavier construction. You have to redesign the city — that may require moving a lot of the population slightly away from the current location. The second is to reforest some of these slopes.

The third step is to undertake engineering measures to stabilise the mountain slopes. The fourth measure is to build retaining walls at the base of the mountain slope so that the river does not cut the toe of the mountains otherwise the mountain slopes will slide. These are some of the recommendations that local people are already making and they don’t want major infrastructure projects. Some of the buildings in Joshimath have been demolished because of severe cracks or instability or weakness. It has to be done, but at the moment the government is reacting in a symptomatic manner. “Okay, the building has lots of cracks. It’s not liveable. Let’s demolish it”. It may be an immediate response but in the long term, you need to conduct serious carrying capacity studies.

Cover photo: Joshimath from Wikimedia Commons