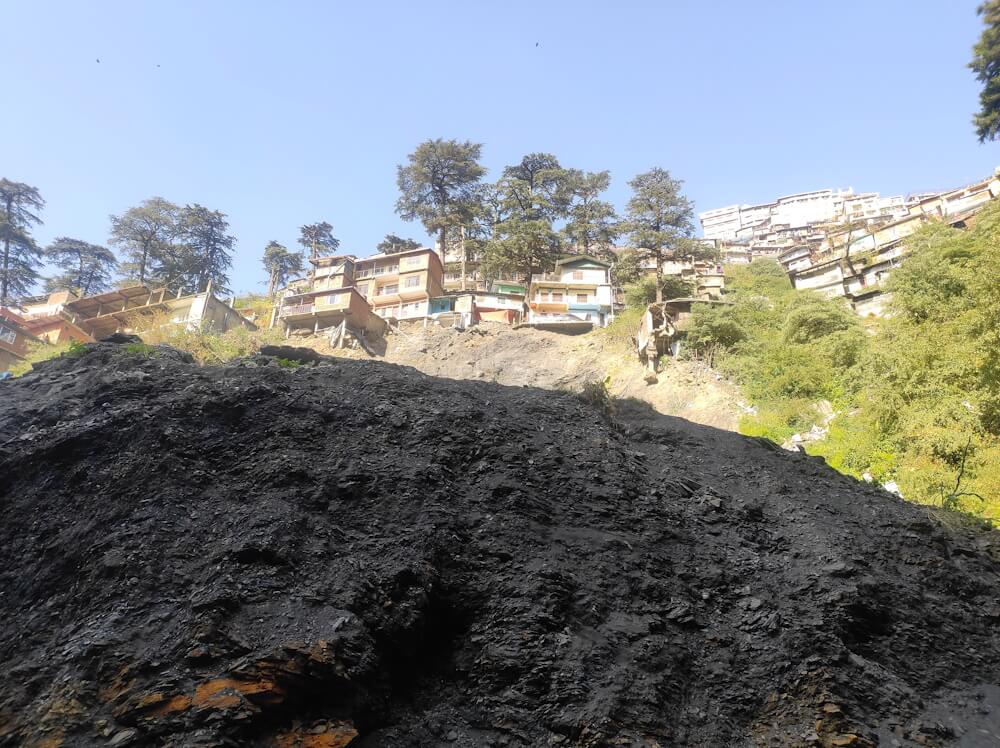

As one looks up at Krishna Nagar, among the oldest settlements of Shimla, from the new bypass road near Lalpani, the bare earth lies exposed along its slope. It is eerily silent amidst the cacophony of constructions around it. The silence is brief, broken by shrieks of ‘Nikal Jao, nikal jao (get out, get out), from the viral video[1] of the five-storied Municipal Corporation’s abattoir building turning to rubble in seconds last monsoon, which play on loop in my head.

Today, there is hardly a trace of the slaughterhouse or that, when it came down during the landslide, it took the lives of two people and hundreds of goats and chickens. They probably lie buried somewhere beneath. For weeks later, workers were sorting scraps of metal and iron rods enmeshed in broken concrete slabs strewn along the hillside where the soil is partly black and partly like fly-ash – the remnants of a landslide in a busy hill city.

The residents whose homes collapsed or are on the verge of falling inhabit the Rajiv Awas Yojna (RAY) quarters located a few meters to the right of the declared ‘danger zone’. In this colony, sisters-in-law Nisha and Suman share a graphic recount of the ordeal they went through that fateful day on August 15: “After several days of heavy rain, it was a clear sunny morning of the Indian independence day. We had not slept the night before as a small boulder had come rolling and hit our roof.” Their tension came from the landslide at Shiv Baodi (underground water spring)[2] that had occurred on the previous morning at Summer hill, a few kilometers away, burying nearly 20 people. The landslide did not spare them.

Several landslides have hit Shimla over the past decade, including Krishna Nagar colony in 2013, taking down buildings. While geo-morphological features and tectonic dynamics of Himalayan topographies make cities and villages here susceptible to landslides, the region has seen a rise in their intensity, frequency and impact.

The impact of landslides

In Himachal Pradesh, the data between 1971 and 2009 shows that four districts – Shimla, Solan, Kinnaur and Mandi – accounted for more than 62 percent of the total landslides, with Shimla district alone registering over 22 percent of total incidents.[3] An official multi-hazard mapping and analysis in 2016 classified over 50 percent of Shimla’s municipal area as moderately prone to landslide hazard and 33 percent as high hazard prone.[4] Krishna Nagar, the largest ward of the Shimla Municipal Corporation, with a population of over 7,000 falls in the latter.

Here, residents routinely lookout for red flags such as blocked nallahs or drains, cracks in walls of houses, and shallow-rooted deodars getting uprooted. “It was just after breakfast that our neighbor Ghufrana and her husband noticed a fine but deep crevice in their tiny vegetable bed; they called out to the others in panic,” says Suman of that August morning. Homes in the neighbourhood were collectively inspected. After checking her own, Suman went down to her mother’s house located just above the slaughterhouse because her parents were away to their ancestral village in Mandi.

“I saw a gap developing between the slope and the check wall built along it. Main samajh gayi ki ab muaaynaa karne kaa waqt nahin (I knew there was no time for inspections),” she recalls. After calling her parents, area leaders and the councillor, she mobilised people to collect valuables, children’s essentials and immediately evacuate. That afternoon, rocks and boulders started shooting out of the ground and the slaughterhouse water tank burst, taking everything down. Her parents’ home was in shambles, her mother traumatised by it all. Fatalities were fewer because it was a public holiday and a Tuesday when the slaughter house is shut, but the manager and a Nepali worker could not make it out on time.

In all, five buildings collapsed while another ten were marked unsafe for occupation. After repeated appeals, the Municipal Corporation finally re-housed residents in the RAY flats for six months, recounts Nisha. Her husband is a driver and Suman’s a salesman; they belong to the Kabirpanthi sect. Mohallas or hamlets named Ghoda Sarai, Laddakhi Mohalla, Valmiki Mandir, Maulvi Ahata, Lalpani, Ravidas Colony and Gaddi Khana reflect the diverse history and ethno-occupational nature – a majority Dalit-Muslim – of these working-class settlements.

Landslides and ‘unauthorised’ colonies

Part of the erstwhile Punjab hill states, Shimla was the summer capital of British India for nearly 100 years. A colonial account on the city’s origin despised that “the natives lived in the valleys, not on hill tops” but the British conquered this transverse spur, reaching it with roads and railways, lifting water from the streams in the valleys to the ridge, installing near-vertical flumes to drain it; carving out royal abodes for strategic governance, culture and entertainment, convent education, sanitarium, residences in the luxuriance of cedars, oaks and rhododendrons.

All this was possible with their free access to natural resources and manual bonded labour of the locals known as begari. Vinod Bhardwaj, former government employee candidly says, ‘Shimla to gareeb ki peeth pe bana hai (Shimla has been built on the backs of the poor).’ The ‘native’ and ‘ordinary’ people were located beneath the mall road at the Shimla ridge by design, so they would remain out of the vision of the royalty. In the middle and lower bazaar, below the cart road came the ‘servant quarters’ which also grew as families who serviced the expanding township came to occupy it.[5] [6]

This “unauthorised” habitation, re-titled Krishna Nagar later, with its often-untold history, is as old as though not as celebrated as Shimla’s colonial heritage spaces. And, by virtue of its location, prone to the worst impact of landslides.

Pradeep Kumar from the Valmiki community, 55, is a third-generation resident in Krishna Nagar. His grandfather came from Jalandhar, and worked as a sweeper in the Shimla Municipal Corporation. His father followed. After his death, Kumar started dealing in scrap. “Grandpa used to have a small room the size of a charpoi,” he recalls. Like others here, they expanded their house brick by brick as families grew. Successive governments promised authorisation of these constructions.

Yet, in a disaster, these were deemed ‘illegal’ and acted against. If their residents were displaced by landslides or floods, they were ineligible for rehabilitation and compensation because they were classified as ‘encroachers’. Without settlements like Krishna Nagar and other lower-class and lower-caste bastis, Shimla would not function. As Pradeep Kumar says: “Milk sellers, coolies, rationwallahs, meat dealers, cleaners all live here. The city cannot function for a day without us but we have been left to fend for ourselves. We cannot afford to buy land so we built tiny rooms atop one another wherever we found space. The Municipal Corporation authorised our water and power connections. How, then, is this illegal?”

Residents of these settlements live amidst a flume choked with garbage. This is one of the five storm water drains running from Shimla’s famous Mall Road through the middle and lower bazaar, right through Krishna Nagar. To the left is a khadd or a natural drain that has concrete walls on both sides. Kumar is critical of this as it tampered with the slope: “The blocked drains are already a menace during the rains. To top that, they began digging into the loose soil using JCBs (excavators) for the river channelisation project, the new slaughterhouse and the road to it. All this destabilised the slope at Lalpani.” Sonia Saberwal, district secretary of All India Democratic Women’s Association, and residents like Suman expressed their opposition to shifting the old slaughterhouse from below the cart road to the new site in 2014 where it collapsed; a park was constructed at its old site.

Construction disregards slopes

There are several other examples where hillslopes deposited with old excavated or eroded material became sites of new construction, plantations, and natural regeneration, though with poor stability, according to Professor DD Sharma from the Department of Geography at Himachal Pradesh University. “The slaughterhouse site was once an area for production of charcoal, which was the main source of room heating in the city till the 80s…The Shiv baodi landslide seems to have originated near the old overburden, dumped along a steep slope or nallah. It is now common to label any heavy rainfall as cloudburst but it needs closer scientific examination.”

Sharma is drawing attention to how Shimla disregarded its natural ecology as construction expanded and how its land-use changes are critical factors in disasters like landslides or flash floods. Krishna Nagar, for example, was not only below the cart road, but also, as some said, situated on eroded material from overhead.

The technical committee which studied 16 locations of landslides and subsidence in Shimla city in last year’s monsoon concluded, in its preliminary report, that the prolonged wet spell which began with rain in April (summer) “had oversaturated the thick debris deposition” in all the major landslide areas including Krishna Nagar. Significantly, the formation of overburden is not just a natural weathering process but also due to land-use changes and deforestation which have further exacerbated the fragility and instability of Shimla, located on the fractured slopes of the ‘Jutogh and Shimla group’ of rocks and metasediments, according to the HIMCOSTE 2023 report.

Seeking ‘greener’ pastures

After independence, Shimla Municipal Corporation which was set up in 1851 to govern an area of about 15 square kilometres with around 25,000 people, saw waves of growth, especially after it also became the state capital. The Census 2011 showed the city’s population at 1.7 lakh. About a third of this are government employees and their families. Residents often say, ‘Shimla toh babu aur lala chala rahein hain (Shimla is being run by bureaucrats and businessmen).

Businesses, small and large, rely on tourism. In the last two decades, Himachal Pradesh has seen nearly a staggering rise in the number of tourists registering its highest tourist footfall in the last six years.[7] In 2022, around 25.6 lakh tourists visited Shimla district which has about 500 hotels and 335 registered homestays (Govind Ballabh Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment 2022).[8] The pressure on the region’s resources is enormous. A Land Use Land Cover (LULC) study[9] of the tehsil, published in 2018, revealed that from 1980 to 2017, the forest cover decreased by 20 percent. Meanwhile, the built-up land increased from 3.5 percent in 1980 to 13.6 percent in 2017 – with a large increase after 2010 concentrated in Shimla town while rest of the tehsil showed sparser built-up density[10]

Despite indicting reports which flagged off climate concerns and unfinished work on basic urban amenities, Shimla’s expansion continues unabated, much of it commercial in nature including the ‘contoured urbanism’ in its peripheral areas emanating from cash-based horticulture and commercial vegetable cultivation.[11] The infrastructure projects and policy moves of the past few years show that Shimla’s development is headed in the direction that neoliberal market-led urbanisation intends.

Whether the construction of the four-lane highways, bilateral loans for tourism development and heritage conservation, declaration of Smart City projects and the Shimla Draft Development Plan 2041.[12] The focus is on fast tracking ‘development’ for tourism and ‘decongesting’ Shimla by extending it beyond the seven hills. The Shimla Planning area has already notified over 22,450 hectares and the state’s urban development authority has acquired land for a new township about 30 kilometres away. Clearly, lessons from the past have not been learned.

The National Green Tribunal, in a bid to protect the remaining green cover of nearly 414 hectares, ordered a construction ban in the core area of Shimla in 2017. However, the Town and Country Planning department’s proposed Development Plan 2041 is pushing back against this as well as the NGT’s restriction on building beyond 2.5 floors on the slopes. The petitioners took the matter to the Supreme Court. Interestingly, the apex court in a separate case, after last year’s monsoon disasters, asked for the “carrying capacity” of Himalayan hill stations. However, in January this year, the court approved the Shimla Development Plan 2041, setting aside the protective orders of the NGT.

As people point out, the Development Plan for Shimla has been overdue since the 1970s and the court had to order it, but the worry is that this ‘planned development’ will run roughshod over key environmental concerns. Mohan Lal Verma, Shimla-based independent journalist, is skeptical of the NGTs judgments and details other contradictions. “The green area concern in the core area is valid but court orders isolate issues and create a wall between people and nature. For example, take the Floor Area Ratio issue. If one had 20 bighas of land they would make a mansion and put a lawn in front of it. But people with five bighas of land in villages where agriculture is loss-making, are tempted to sell it when a road comes up nearby. Marginal holders put up a multi-story residence along the road so that children can access education and they can have a shop as a livelihood option. In the mountains, if people don’t have room to build a contoured structure, they go vertical,” he explains.

What Verma points to is a systemic crisis of urban imagination without factoring in natural features and societal inequities, which further complicates the issue. The way forward is a deeper engagement with the human-nature dialogue in all its complexities, on the ground amongst the most common and marginalised peoples. Relevant political actions can emerge only from such democratic participation. For now, Shimla’s urban narrative remains firmly chained to its colonial ‘hill station’ legacy, paradoxical to its multiple identities and defying socio-ecological sensibilities of the mountains.

Manshi Asher is a researcher, writer, activist living in the Dhauladhar valley of Himachal Pradesh. Over the last two and a half decades, her work has involved documentation, campaigning and activism on environmental justice, forest and land rights issues. In 2009, she co-founded the Himdhara Collective, an autonomous environment group that extends solidarity to Himalayan communities’ voices to protect their livelihoods and landscapes. She identifies as a feminist who finds joy in grappling with various struggles and inner dilemmas at the intersections of caste, class, gender and ecology in everyday life in the mountains.

Photos: Manshi Asher