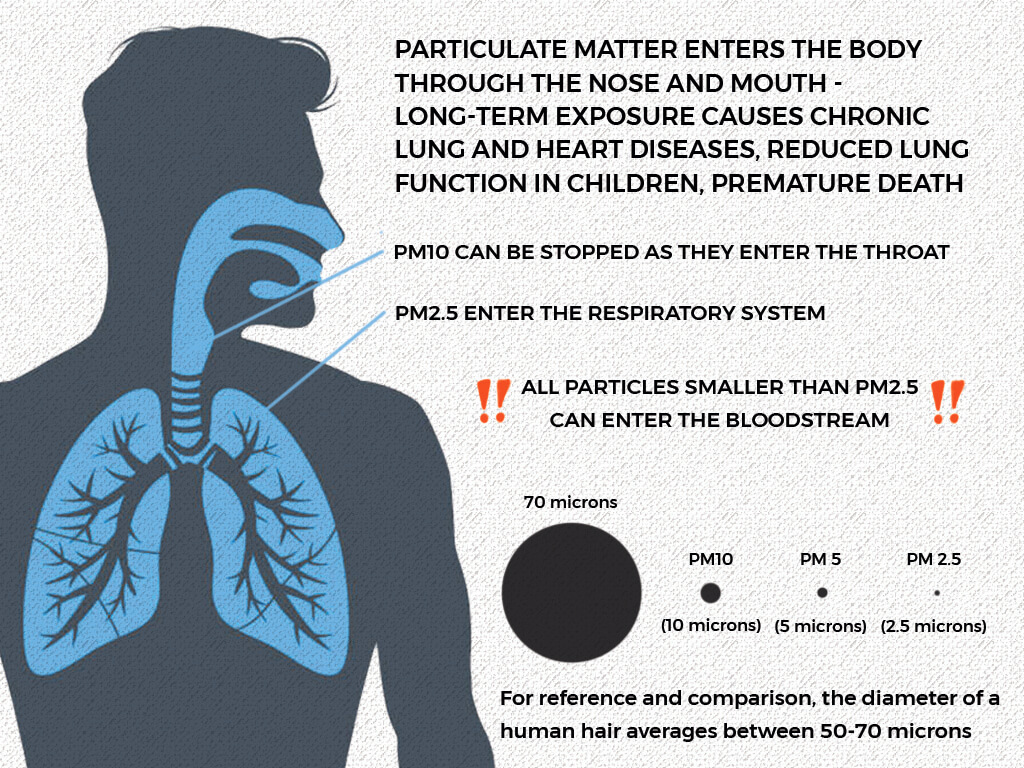

Itchy throats, watery and tingling eyes, running noses, wracking coughs, headaches, difficulty in breathing, a weird taste on the tongue from the fine dust, and more. Polluted air, dense haze and dust are making us sick. The impact of bad air on people’s health is, by now, well established.[1] As more and more cities around India make it to the dubious list of the top ten worst polluted cities of the world[2], an increasing number of people are falling ill with respiratory ailments. Children, senior citizens, and outdoor workers take the brunt of the pollution. Face masks are back in circulation though they offer little defence against the noxious substances and Particulate Matter (PM10 and PM2.5) in the air. The smog clouds skylines in cities too, shrouding popular landmarks with a layer of particulate matter, blurring our familiar landscape.

The list of cities impacted by bad air is well known; more cities in India or Asia are added every year and the situation worsened by the impact of climate change. Yet, the action against air pollution, from the central government to the state and local civic bodies, has lurched along without comprehensive action plans, with only half-hearted measures such as anti-smog towers and water sprinklers to keep down the dust. People are paying the price.

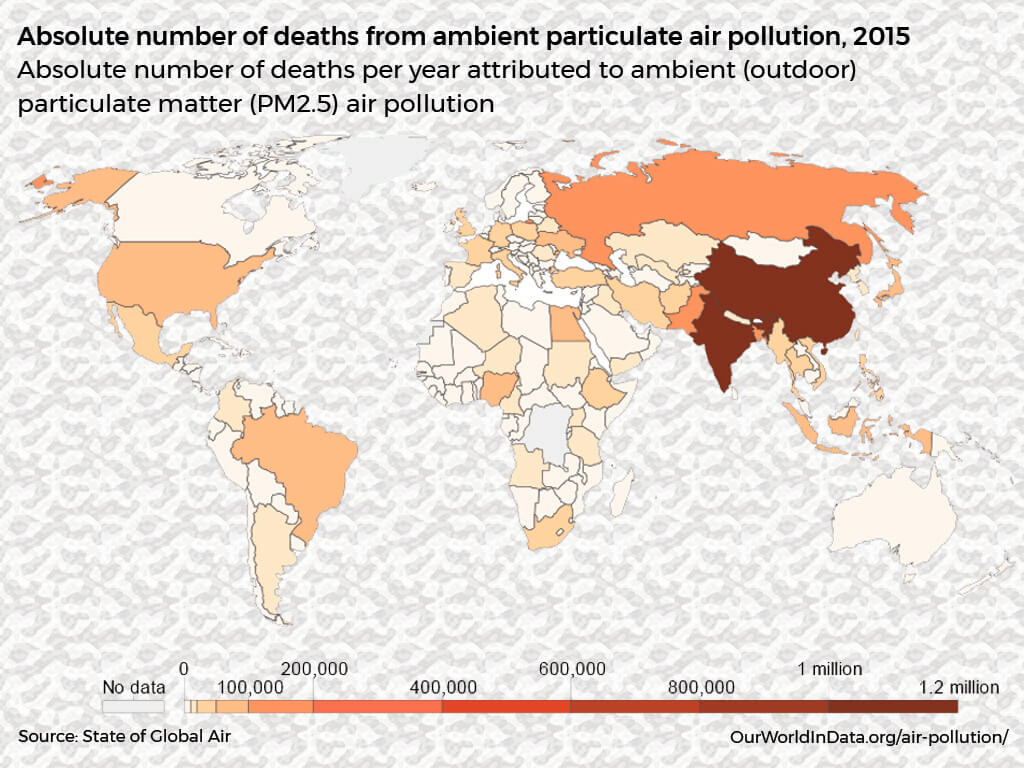

More than 2.3 million Indians died prematurely due to pollution in 2019 of which 1.6 million deaths could be traced to air pollution, found a study published in Lancet. Unsurprisingly, India topped the list of low and middle-income countries which accounted for more than 90 percent of pollution-related deaths around the world.[3] The State of Global Air report, released in August this year, found that India is responsible for 59 percent of the world’s increase in pollution. Across India’s northern plains, its most polluted region, people’s life expectancy is likely to reduce by eight years if the current pollution levels persist, the report projected.[4]

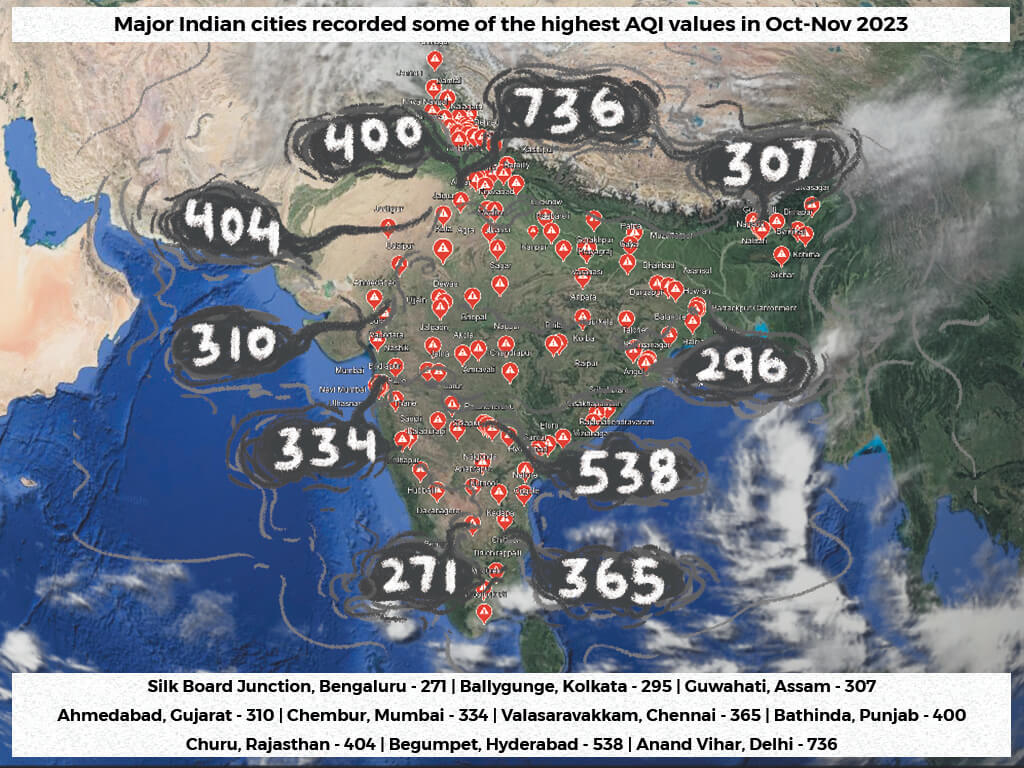

How bad is it, really?

New Delhi, India’s capital, is the most polluted megacity in the world. The average particulate pollution here is more than 25 times the WHO guideline at 126.5 μg/ m3. The last two decades have shown a dramatic rise in the pollution levels in the states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh – 76.8 and 78.5 percent respectively – which are home to more than 204 million Indians, where the average person could lose 1.8 to 2.3 years of life over that in 2000.[5]

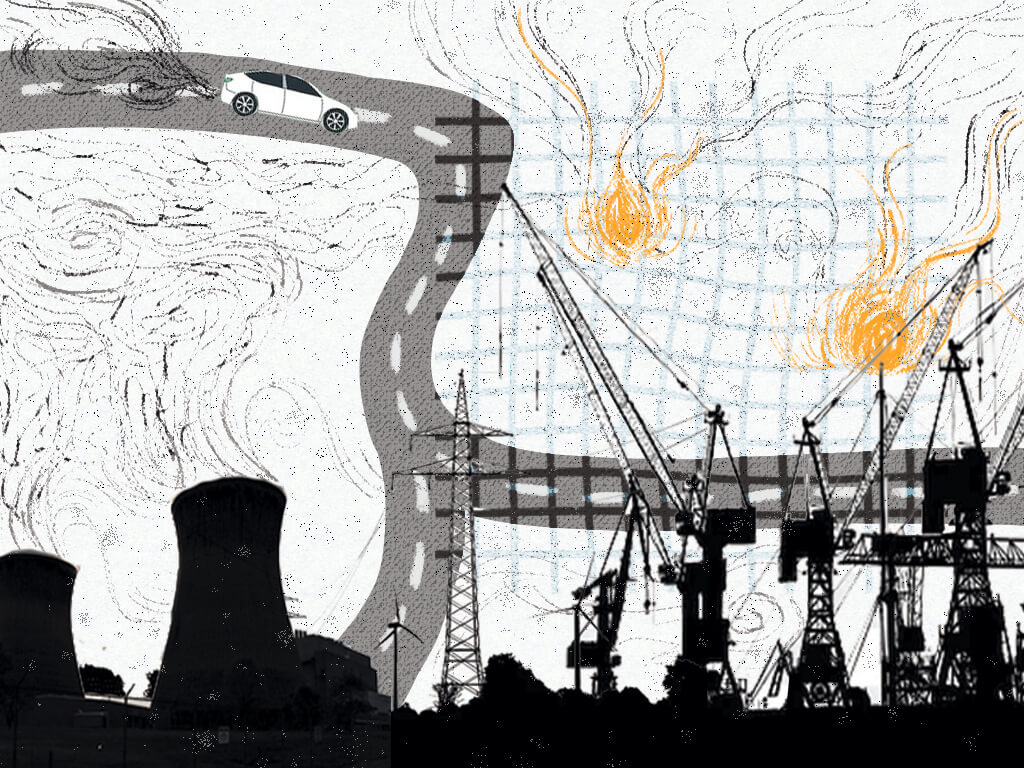

While Bengaluru and Patna suffered from anthropogenic dust and waste, long-range transboundary pollution impacted cities like Mumbai, Kolkata and Hyderabad in 2018. Delhi saw agricultural burning contribute the most to its deteriorating air the same year. Industries and power plants wreaked havoc with Surat’s air, and vehicular emissions made breathing difficult in Thiruvananthapuram.

Vehicular emissions need containment, but other sources such as construction and road dust, industrial fumes, wood and open waste burning also require attention. Official actions against air pollution happen seasonally and barely scratch the surface. For example, official measures focus on reducing people’s exposure to emissions rather than long-term policy changes that address the cause of emissions. Governments issue guidelines on using masks or staying indoors without addressing sustainable public transport or waste management.[6]

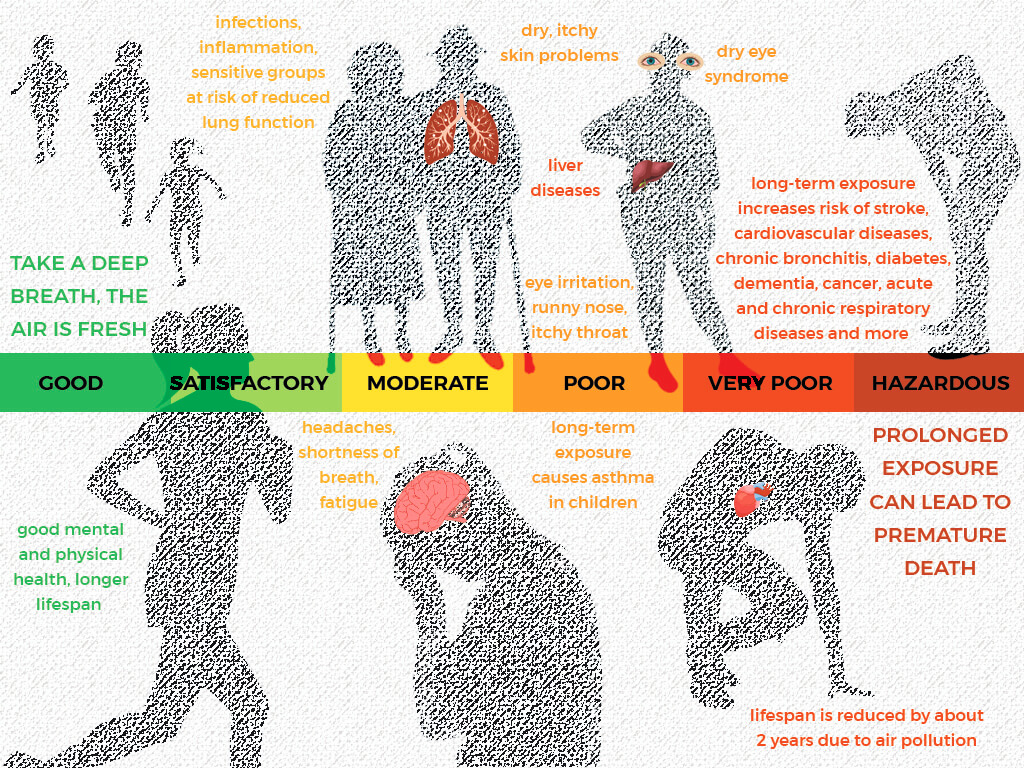

India has one of the highest number of deaths due to air pollution.“The longer one is exposed to air pollution, the greater the risk of serious health harm,” states this report.[7] Air pollution harms more than the lungs. Besides worsening asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), it can precipitate heart disease, stroke, cancers, and low birth weight.

The state of air and health appear grim, even alarmist, but governments appear lackadaisical. How bad should it get before they realise that bad air is a silent killer? When will comprehensive measures be adopted, if not now?

Where does the buck stop?

The National Clean Air Program (NCAP) was rolled out in 2019 to reduce emissions in major polluting cities by 20-30 percent by 2024 relative to 2017 levels. Last year, the target was revised to reduce PM pollution levels by 40 percent by 2026.[8]

The NCAP has set down National Ambient Air Quality Standards to monitor air pollution in cities across India. The 114 cities which violated the standards for PM2.5, PM10 or NO2 for five consecutive years were tagged as ‘non-attainment cities’. In 2019, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) directed 20 more cities to develop their clean air plans.[9]

A study by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) found that only 25 out of 102 cities’ clean air plans had data on emissions from different sources. This means cities are not fully aware of the pollution sources though the Air Quality Index varies widely from one area to another.

The study also found that authorities are not legally bound to review and update the clean air action plans. The responsibility to control air pollution would be best at the level of individual cities. However, the absence of a single body to regulate the coordination and implementation of the plans may “result in fragmented accountability and overlap of responsibilities,” the study also found and recommended assigning specific roles to agencies to implement mitigation measures.[10]

The Air Quality Index (AQI) for cities hit the ‘poor’ to ‘hazardous’ categories in November. In Mumbai, as the air quality worsened, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and Maharashtra Pollution Control Board issued strict instructions for the construction sector which is a major pollutant but did not similarly address emissions from transportation. The guidelines issued earlier were made more stringent.

Delhi’s Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) is often cited as a remedial measure[11] to be implemented in stages as air quality worsens. Delhi’s environment minister Gopal Rai announced that the GRAP-related restrictions would be enforced[12] but the millions suffered when the city’s AQIs went off the charts around Diwali.[13] The November-end unseasonal rains allowed a relaxation of Stage III restrictions of the GRAP – a halt in construction and demolition activities, stopping stone-crushing and mining – but Delhi’s AQI still hovered at 312 or ‘very poor’.[14]

Where are the shortcomings?

The problem is known, studies have shown the way ahead, and agencies are being forced to take measures against air pollution, but improvement on the ground has been either slow or imperceptible. A key reason for this, based on interviews we conducted, was the cyclical pattern of awareness and actions. People become concerned about polluted air when the air turns hazardous in October and the authorities initiate actions – some of them gimmicky – around the same time. This seasonal approach has not worked. Reducing and combating air pollution has to be round the year.

A study found that, in north India, people’s attention towards air pollution rises during the second half of the year because of stubble burning and seasonal weather changes. The media coverage of air pollution, which drives public discourse and government action, also tends to be seasonal. The study points out that the lack of year-round conversations means that the public demand and sustained pressure for long-term solutions is low.[15]

What actions can be taken?

Cities need comprehensive clean air action plans and round-the-year implementation to mitigate air pollution rather than emphasising personal measures such as masking and staying indoors or shutting down schools.

Besides comprehensive climate action plans, cities need to draw up non-negotiable GRAP, according to experts. This would make responsibilities of all agencies clear and graded action can kick in systematically. People’s awareness and activism demanding clean air all through the year can also have an impact on governments’ actions, they add.

Each source of air pollution must be tackled at source. Without this, all else is like band-aid on a bleeding wound. The causes and sources are well mapped even if their exact contribution to overall pollution fluctuates. Indoor air pollution needs to be addressed too; it increases the prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) among those exposed to firewood or charcoal. People living in urban slums, research shows, carry a five times greater risk of developing TB than people in other areas.[16] A study in 2014 in Pune, Maharashtra underscored the association of TB with indoor air pollution.[17]

Schemes like Ujjwala, subsidised cooking gas cylinders, need a revisit because people stopped using the LPG connection due to the cost of replacement cylinders. The essay[18], by Harvard Public Health, suggests the need to understand how fuel is used in low-income households and call for an increase in LPG subsidies for poor households.

What has bad air meant for people’s health and the economy?

There is no milder way to say this: The long-term impact of exposure to pollution is physical and mental debilitation, even death. In 2019, the deaths due to air pollution in India were 18 percent of the country’s mortality. Around the world, one-fourth of the premature mortality is due to air pollution.[19]

The Global Burden of Disease data shows that, as of 2019, air pollution from Particulate Matter, ambient particulate matter, and household air pollution contributed or led to conditions like ischemic heart disease, intracerebral haemorrhage, ischemic stroke, tracheal and lung cancer, COPD, lower respiratory infections, and neonatal preterm births among others.[20]

There is an economic impact too. The loss of productivity from premature deaths and morbidity due to air pollution accounted for economic losses of US$28.8 billion and $8 billion respectively in India in 2019, noted a study published in Lancet. “This total loss of $36.8 billion was 1.36 percent of India’s gross domestic product (GDP). The economic loss as a proportion of the state GDP varied…was highest in the low per-capita GDP states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. Delhi had the highest per-capita economic loss due to air pollution, followed by Haryana in 2019,” it detailed.[21]

Other studies pegged the loss higher. “Air pollution costs Indian businesses about USD $95 billion every year, around 3 percent of India’s total GDP,” stated a report by Dalberg Associates with the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII).[22]

A less-discussed impact of air pollution is on mental health in cities. When high AQI deters people from being outdoors, Particulate Matter is everywhere, respiratory infections and diseases are on the rise, and schools are shut down as part of emergency measures, the field is set for mental health issues such as anxiety, depression and loneliness. Read the essay here.

The World Health Organisation’s document, ‘Urban Design for Health’ for the European region in 2021, set guidelines to build cities in ways that promote health.[23] Along with tools that assess open spaces, mobility and safety, among other factors, it emphasises the power of policies to ensure mental health and social well-being. The concept of 15-minute cities is increasingly gaining momentum around the world though India’s cities have organically followed this. It can make residents healthier, happier and more sociable while also blunting the impact of climate change by encouraging shops, schools, healthcare and social spaces within walking distances in neighbourhoods which means fewer people use motorised transport.[24]

Most cities in India seem perpetually ‘under construction’ which contributes to air pollution. The action to be taken is well known; the question is whether the authorities can be held accountable for the work they are required to do.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.

Illustrations: Shivani Dave