‘You not only cut down the hills, you destroy a whole culture’

Bhanwar Meghwanshi, 50

Bhilwara, Rajasthan

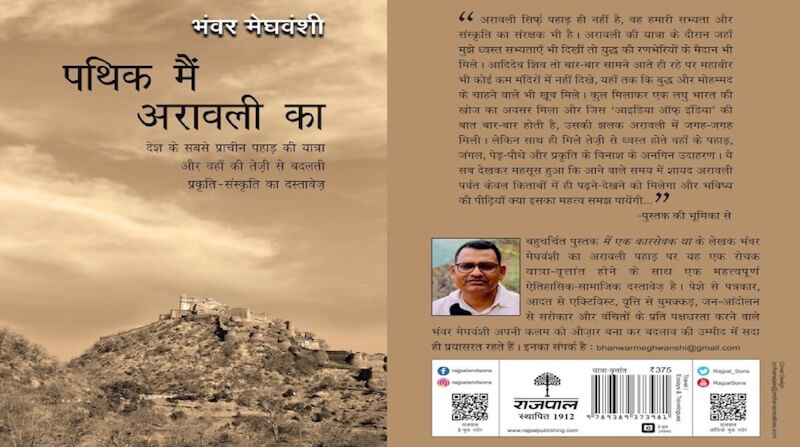

“I am an author and human rights activist. For the past 20 years, I have been working in the districts of the Aravallis – Bhilwara, Rajsamand, Pali, Ajmer and Udaipur – raising issues from the Right to Information and employment guarantee to education, health, climate and atrocities on Dalits, tribals and minorities. I work with the People’s Union for Civil Liberties and was earlier with Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS). I travelled in the Aravallis and have seen the entire ecosystem change from being clean and without crowds to the road construction and tourism industry cutting down the hills to build hotels with lake views and rivers views. And there was large-scale mining. If this continues, the Aravallis will only remain in the name; so I began its documentation. The book, called Pathik Main Arawali Ka, was published in 2023 by Rajpal And Sons.”

“People are fighting against illegal mining in Neem ka Thana, Kotputli, Alwar, Rajsamand, Jaipur, Jhalawar, or Pirohi. There is a big issue of silicosis in Pindwara. Those who work there get silicosis; many die. Places like Haldighati, Mangarh Tribal Rebellion, Bhula Baloria are all sites inside the Aravallis. There are religious places – Rineshwar Dham of the Adivasis, Nathdwara, dargah of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, the Brahma Mandir at Pushkar, Tavasthani of Bharatari Gorakhnath, and Shilalekh of Ashoka. There are two major Jain temples at Delwada and Ranatpur. So, there’s Jainism, Shaivism, Buddhism and Sufism in the Aravallis besides places of war, religious places, and magnificent natural places like Lake Nakhi.”

“The Aravalli range has protected India by stopping the Thar desert from moving forward. Raisina Hill, Rashtrapati Bhavan, and the JNU in Delhi and the entire Gurugram were built on the Aravallis.Without the range, the desert would have come forward. Secondly, because of the Aravallis, it rains in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan; without it, clouds would have rained down in Hindukush or Baluchistan, and heat waves would rise and destroy north India. Many rivers originate here because of which water is recharged for the fields, in the wells. All the rivers are connected, so when there is mining somewhere, all the streams are cut off and rivers dry up, which means the end of people’s farming on a large scale which, in turn, threatens food security.”

“There’s a lot of wildlife in the entire Aravalli range, many rare medicinal plants used in Ayurveda, woodlands and desi seeds, tribals who have lived there, our devas, our seeds. The hills have saved them. So, not only are you cutting down mountains, but also destroying a whole culture, a whole habitation. The environment is a concern but a lot more is involved – the people, culture, civilisation, history, and spirituality. We call ourselves the people of Sindhu-Aravalli culture. We have fraternity and brotherhood, Hindus and Muslims learned to live together, learned to live with less water. So, you find communities like Geeta, Mehrad, Kathad, Mehu that have both Hindu and Muslim beliefs. People have a deep emotional connection with the Aravallis. So, they stood up everywhere, across party, religion, caste, creed to save ‘our’ Aravallis.”

“Bhajan singers wrote bhajans, poetry was composed, artists made art on sand, cartoons were drawn. Those who could agitate on roads did that, some wrote a letter with blood, some did cycle yatras, others climbed to the top of the highest mountain in Sikar, some tied a protective chain to the hills. Then, there are people like us who have been campaigning for the Aravallis – Tarun Bharat Sangh, a petitioner in the Supreme Court since 1990; Rajendra Singh, Kailash Meena, and Radhe Shyam Sukla fighting against illegal mining. In Jaipur, Kavita Srivastava and Naujawan Youth, went from hostel to hostel in universities, colleges, and schools. If nothing, people began changing DPs on social media and smartphones. People did something every day, it’s still going on. Aravalli Bachao Jan Andolan will continue; it’s not like the Aravallis have been saved. The experts’ reports are by bureaucrats or geologists, geomorphologists and environmentalists, but people of the Aravallis have no voice. The mining is illegal, dumpers are going around, 300 crusher plants are running in one village. How will people live? How will the whole mountain, being crushed, survive?”

‘How can people in the highest positions make such absurd decisions?

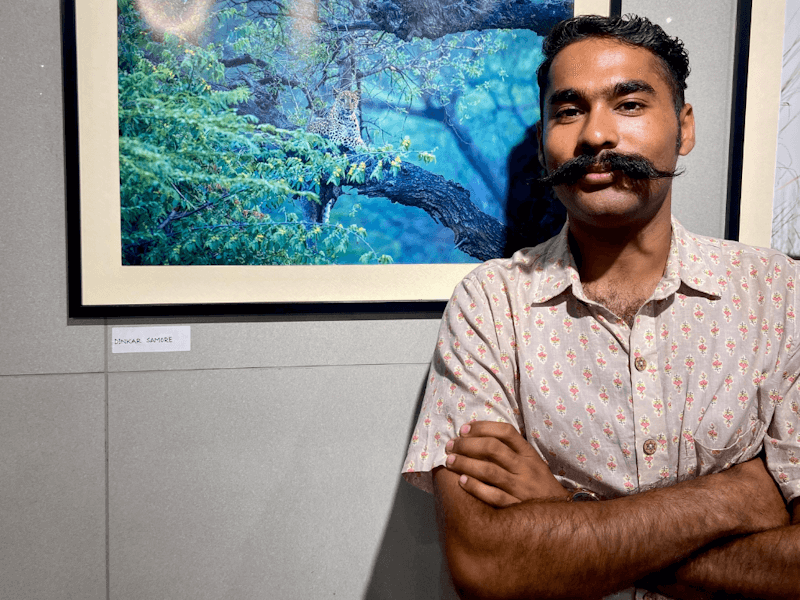

Dinkar Samor, 28

Alwar, Rajasthan

“I am a naturalist, an environmentalist, conservation photographer and a budding filmmaker. I don’t do activism but I support people when they gather. I have grown in the lap of the Aravallis and went to a protest in Jaipur by the group raising voice for Dol Ka Badh forest. I did not see many students; it was more communities of farmers and villagers who were gathered by different organisatons. In Delhi and Haryana, I saw protesters a little awakened by environmental aspects.”

“When it comes to animals, birds or even rocks, we humans think of economic benefits for ourselves but don’t know what we are doing in the ecosystem. It’s a greedy way to see but the Aravallis are doing a lot for us. They are the hydrological backbone of north-western India, support rich biodiversity, and are probably two billion years old. But we humans just look at them and define them. Many things that this government is doing does not make sense but our energy, time and resources go into protesting them. How can people sitting in the highest positions make such absurd decisions? The stay came eventually but so much of people’s time and resources were wasted.”

“For 7-8 years, I have been doing a lot of birding in Alwar where I grew up. There is also the Sariska Tiger Reserve and Lake Silisa in the lap of the Aravallis. I used to go every day to some part of the buffer forest of the Aravallis and watch birds. The forests and livestock are important to the pastoral community here. But not all of the Aravallis are protected by the forest department. There’s a lot of illegal mining around Alwar too. I have seen whole hillocks go and see remnants of some.”

‘People have lived here for centuries, their stories are connected to hills’

Ishwar Singh, 28

Rajwa, Rajasthan

Worked with Avsar Collective[1] and Majdoor Kisan Shakti Sanghatan[2]

“On the Aravallis, people protested earlier too. Now, people are saddened. There was mining everywhere. Some lost their land; others lost cattle. So, people protested. I had written an article too.[3] People came up with ways to stop mining, women’s groups had united. We tried to stop them. We worked with MNREGA making check dams or planting. Because of the effects of mining, there is not much farming. Most people keep goats but grasslands are needed for that. Mining started there too. Today, they are told ‘you can’t live here, you don’t have this land’. Where will people go?”

“The people who mine here are so greedy that they want to take everything. It’s easy for them to scare the locals, offer money to people resisting. Our protest started with MNREGA law change and included Aravallis. People started posting on social media and influenced others. Some organisations as well as political parties like the Congress have been standing with the people; local Congress MLAs have spent on this. We are resisting through songs about the culture, the lakes, the people of the Aravallis.”

“There is definitely anger and frustration. Writers, workers, Dalit organisations are all involved. We are planning a yatra from Gujarat to Delhi. We also want to focus on padyatras in various villages and towns to create awareness about land rights and MNREGA. People’s stories are connected to the Aravallis because they remember where they have taken their goats, camels, bulls. People have lived here for centuries. There are thousands of people’s stories with the Aravallis. People’s songs, temples, are all here, all parts of the Aravallis story.”

‘The destruction of the Aravallis means your constitutional system has collapsed’

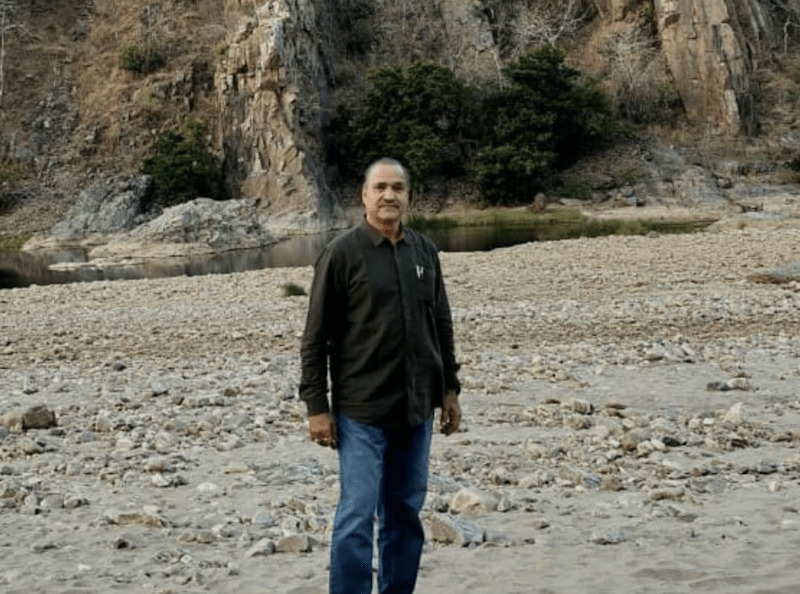

Kailash Meena, 60

Environmental activist

“I have been fighting for 30 years to save the Aravallis. Even before the Supreme Court’s November order, the situation was very bad. Although the court said ‘no mining’ everything is going on as usual. For people who live in the Aravallis, their main source of income is agriculture and livestock which means they are totally dependent on ground water, rivers and green spaces. However, mining has destroyed and polluted all the rivers and streams, and reduced ground water levels, affecting people’s livelihood. So, the people raised their voices.”

“In Rajasthan, only 32 blocks have drinking water and there’s an ongoing drought. There are reports of the groundwater board. Because of mining, in nearly every district, the land has turned barren on a large scale, mining has caused huge losses to a large number of people. In such a situation, when the Aravallis face an even greater threat, the revolt is natural. From Gujarat to Delhi, every 20-30 kilometres, there’s a strong protest. The politicians and bureaucrats are contacting each other. The social impacts of mining have also included criminalisation of local youth. They were in government or private jobs or did farming – all this ended. This fight is a continuation of what many of us have been doing for decades. In October 1999, some of us went from village to village and wrote songs to make people aware that some want to kill our jungle for its golden egg.”

Photo: Ishwar Singh

“Another vision is possible. Local people have fought for 15 years to preserve Girjan River which too originates in the Aravallis. A marble company took 180 hectares near it for mining iron ore. The police keep charging those who oppose the company. The grim situation persists, overloaded trucks ply continuously on roads which are in poor condition. A survey found that 243 people died in 11 months last year in Sikar and Kotputli districts in north Rajasthan’s Aravalli belt; three police officers died after being run over by overloaded trucks. I complained but nothing happened.”

“In December 2011, they tied my hands, took off my clothes and paraded me. This affected my personal life. My elder brother died of a heart attack a few days later. I tell the intellectuals: You have the entire constitutional system, the judicial system, science and technology, the police security system but you could not stop the mining and the destruction of the Aravallis which means your constitutional system has collapsed. In the name of development, they are playing with people’s lives. When 2025 turned out to be one of the hottest years, when Delhi began to suffocate with bad air, they understood the Aravallis should be saved. But we who struggled for years are called ‘anti-government’ and ‘anti-development’. In the 27 districts, almost everyone is affected. We are fighting, with no resources, to save our existence. I ask the city people to support our struggle. Saving the hills means saving the air in the cities too.”

‘After the SC verdict, 126 mining leases were allegedly auctioned’

Dr Sunil Dubey

Chambal, currently resides in Udaipur

Joint Managing Trustee of Institute for Ecology and Livelihood Action, member of National Academic Committee of Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, and IUCN World Commission member. His podcast is titled ‘Aravalli ki kahaani’ (The story of Aravallis)

“I am a resident of Chambal region, on the eastern side of Dholpur district in Rajasthan. My roots and forefathers are from the Aravallis. The place I live is like a saucer with the Aravallis all around. So, I have a relationship with the hills. I have also been a professor of environmental science and a wildlife scientist. Aravallis are my own mountains. In the period when the Asian-Eurasian plate collided, the original formation of Aravallis went through the settlement process. The geological upliftment is still going on in Aravallis. Thousands of years ago, in the west of Aravallis, the Saraswati river used to flow, its tributary was from south Rajasthan.”

“From this evolutionary process, the definition given now is a mistake. Of the 34 National Geoheritage Sites, 12 are in the Aravallis. There is population density, rich biodiversity with 41 animal and 49 plant endemic species. There are Stromatolites fossil sites. In the new definition approved by the Supreme Court, these areas do not fall within 100-300 metres. As a geoheritage site, as an endemic species habitat, 100 metres or not, the hills should not be touched. The Aravallis are the lifeline of western India. The big river basins of Luni, Banas, Mahi, Sabarmati, Chambal rivers all originate here; thousands of rivulets and wetlands arise here. The wild banana is found here even today. If its habitat is lost, the species will end.”

“To say that mining is happening in less than two percent is a lie. Those who have not seen and understood the formation of Aravallis, or intentionally ignore it, find only mineral deposits. After the SC verdict, 126 new mining leases were allegedly auctioned in December; 50 of them in Rajasthan and all in the Aravallis. The bitter truth is that the minerals are there but there’s also the question of sustainability. The rampant mining of stones is destroying the morphology of the entire Aravalli range. There’s also the textile industry and tourism. The mountains are disappearing, so is the groundwater, soil surface, and native species. There’s fine dust all over; Rajasthan has the highest number of cases of silicosis. The highest peak of western India, Mount Abu, has been destroyed. Why should there not be any regulation on mining?”

“Communities here have a relationship with the mountains, with nature, so there are folklore, stories, legends, mythologies. Tribals here consider the hills to be god, called Magra Bawji; there are sacred groves too. They don’t deforest or hunt. Trees are not cut, mining is not done, animals not killed; leopards there do not harm them. People understand the hill is home to leopards. This applies all over the Aravallis. This is the reason so many protested.”

‘By January 26, stop all construction and mining in the Aravallis’

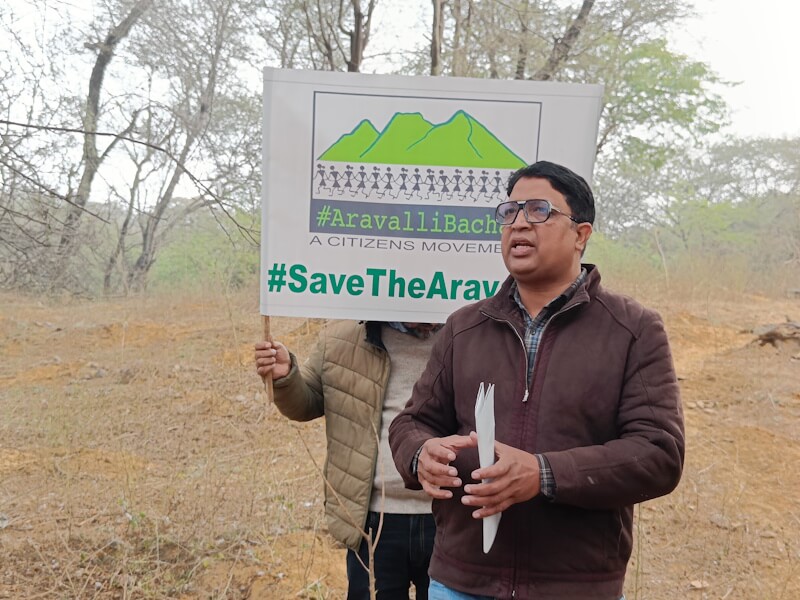

Lieutenant Colonel (retired) Sarvadaman Singh Oberoi

Resident of Gurgaon since 2001,

Managing Trustee of Aravalli Bachao Citizen’s Movement

“We are citizens of the world too and international peace is one of the guiding principles of our Constitution, but international peace will not be if there is international mayhem on the natural assets. Across the world, natural assets are being stripped. We want the Aravallis to be declared a UNESCO biosphere – and this has to be done now. We have been working with the government. The bureaucrats understand what we say but wonder how it can be managed with all the political noise around and the business interests. The only way is for citizens to come peacefully, exert their power over the political and business nexus quietly.”

“Also, a judicial review must be done of the present system. If the Supreme Court does not, under Article 142, stop mining and construction, the Aravallis will be completely leveled. There will be no mountains, nothing to stop the flow of dust from the Thar desert. And Delhi is going to be overtaken by AQI 2500 by next year. We demand that by January 26, when India celebrates the adoption of the Constitution, there should be a stop to all construction activities, mining, and industrial expansion here. They cannot define the Aravallis; God has given us the Aravallis.”

‘If we do not stand up today, future generations will question us’

Iqbal Khan Amrohi

Founder of Jazba Foundation

Travelled 165 kilometres by scooter from Amroha, Uttar Pradesh, across Rajasthan and Haryana to be part of a baithak.

“On December 24, when I began reading and watching the news about the Aravallis, I realised how critical they are. They are our lifeline, essential not just for the environment today but also for the future. Within two days, I planned everything and travelled to Delhi, Rewari, Alwar, Jaipur and Amer Fort. I made posters and banners and spoke to people about the importance of the Aravallis. This mountain range is millions of years old. It protects north India from the desert. If the Aravallis are destroyed, the consequences will be immense. Water will disappear, food systems will collapse and life itself will be threatened.”

“In Alwar, I saw a large lake about 15 kilometres away. When I asked children what they wanted, they said they wanted the Aravalli mountains to stop being cut. Everywhere I went, people showed love and support. Many shared stories of how the mountains around them were being destroyed. If we do not stand up today, future generations will question us. Awareness is the first step. Today we may be fifty people, but we need more.”

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS), she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover Photo: One of the protests in Rajasthan. Credit: Bhanwar Meghwanshi