The much-awaited Mumbai Trans Harbour Link (MTHL) was finally completed and opened for use this January, and was celebrated as a key infrastructure piece connecting Mumbai and Navi Mumbai. It is a pending project from the 1960s and has waded through many political and economic challenges.[1] The reasons to link the two urban areas have been manifold – decongesting Mumbai to ease its population density, making affordable housing provisions in a planned manner in a greenfield area, and creating open spaces at different scales, nature and characteristics.

This essay traces the planning premise of Navi Mumbai, the process of making the satellite city, and makes an assessment of the open space planning-led social and environmental well-being of people, who came to live in the new city. The idea of planning a satellite town on a greenfield area was a big opportunity for providing housing, infrastructure and open spaces, which has succeeded as a plan, not so much on the decongesting agenda.

Modern planning in India has been largely influenced by colonial planning principles and reinforced with the conviction of English urban planner Ebenezer Howard’s ideas of the Garden City.[2] This approach laid emphasis on resolving the problems in the core city by planning new cities outside the core city. Navi Mumbai, as the new twin to Mumbai, was planned on similar lines across a partly greenfield area.

Two parallel streams of effort made this possible. On one hand, it was the cumulative effort by formulation of the Barve Committee recommendations, the Development Plan 1964 of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, and the recommendations of the Bombay Civic Trust and the Gadgil Committee. On the other hand, planners, architects and engineers joined the effort either independently or in step with the official purpose. The trio of reputed architects Charles Correa and Pravina Mehta and engineer Shirish Patel drew up the master plan and presented it to the then Maharashtra government for implementation. The City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra (CIDCO) was formed to implement the master plan and bring the planned city to fruition.

Navi Mumbai was initiated to resolve Mumbai city’s growing concerns mainly in transportation and housing. The dichotomy of burgeoning employment opportunities for a growing population and the state’s inability to provide good housing options within Mumbai city gave rise to peripheral towns around the core city connected through its suburban railway system or a slew of slums within the city itself.

Both cases negated the idea of building a satellite city around Mumbai. It was not fulfilling the need to improve the living conditions of the current housing which were near their jobs. Hence, the idea of planning a large new city across a similar area of 343 square kilometres, across the Thane Creek to accommodate up to 10 lakh people gained impetus, driven by multiple forces of economy, migration, politics and more.

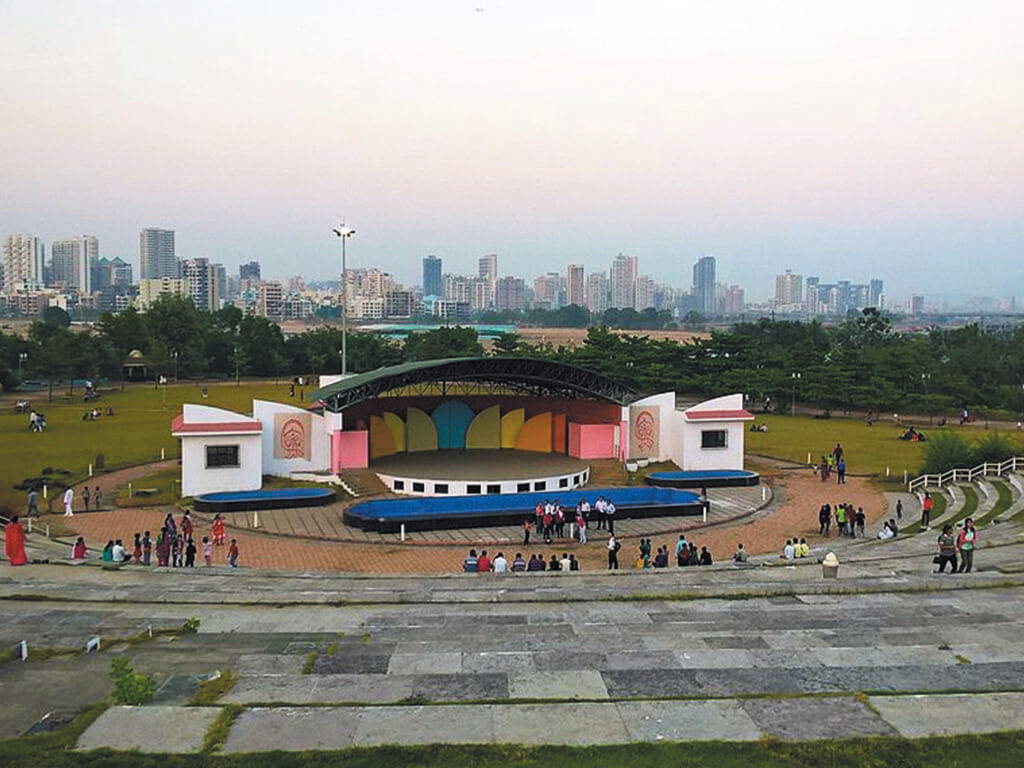

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The plan and approach

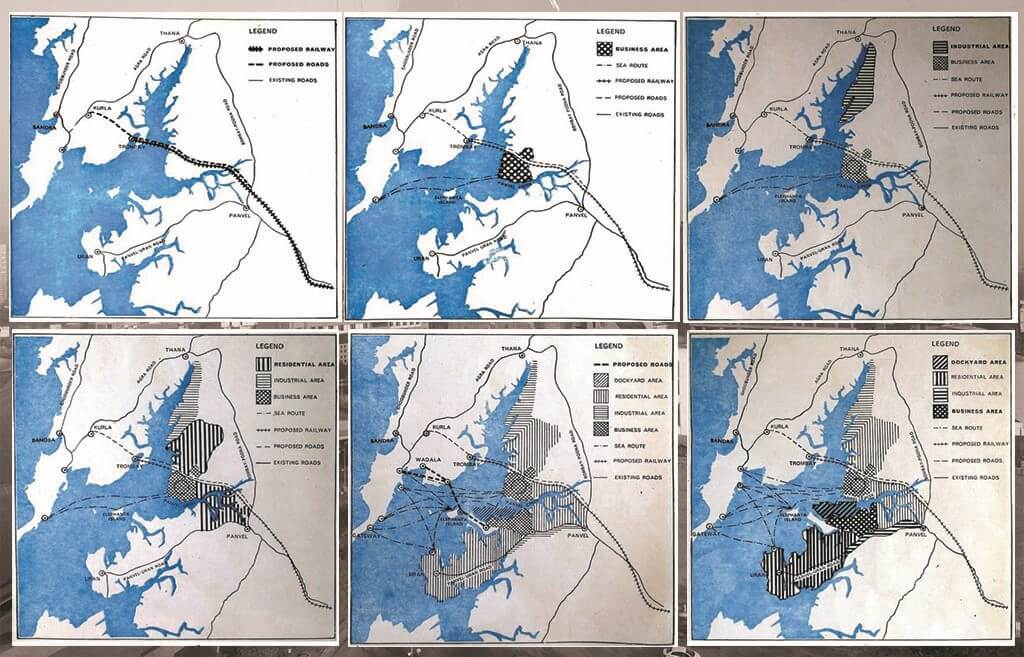

The following stages, indicated below in maps, were considered in the master plan for the development of Navi Mumbai: road, rail and sea links between Mumbai and Navi Mumbai, shifting of the Central Business District (CBD) from the core city centre to the Belapur node of the new city, expansion of existing industries in the new city, adequate housing for all with infrastructure provisions in each of the planned nodes, port and dock activities at Nhava Sheva (which the MTHL now connects to), and more transportation linkages.[4]

The Navi Mumbai master plan adopted the model of a self-reliant polycentric node and brought in several other new concepts in the seven planned nodes. Vashi was planned as a commercial hub with housing across strata, the Agricultural Produce Market Committee was located in the vast stretches of nearby Sanpada, the CBD and government offices were planned in the Belapur node connected through rail, road and sea linkages.

The master plan itself provided for wide roads, holding ponds, commercial use of railway station buildings, educational institutions, and, importantly, housing for low-income, middle-income and high-income groups with accessible green and open spaces meticulously located within each node.

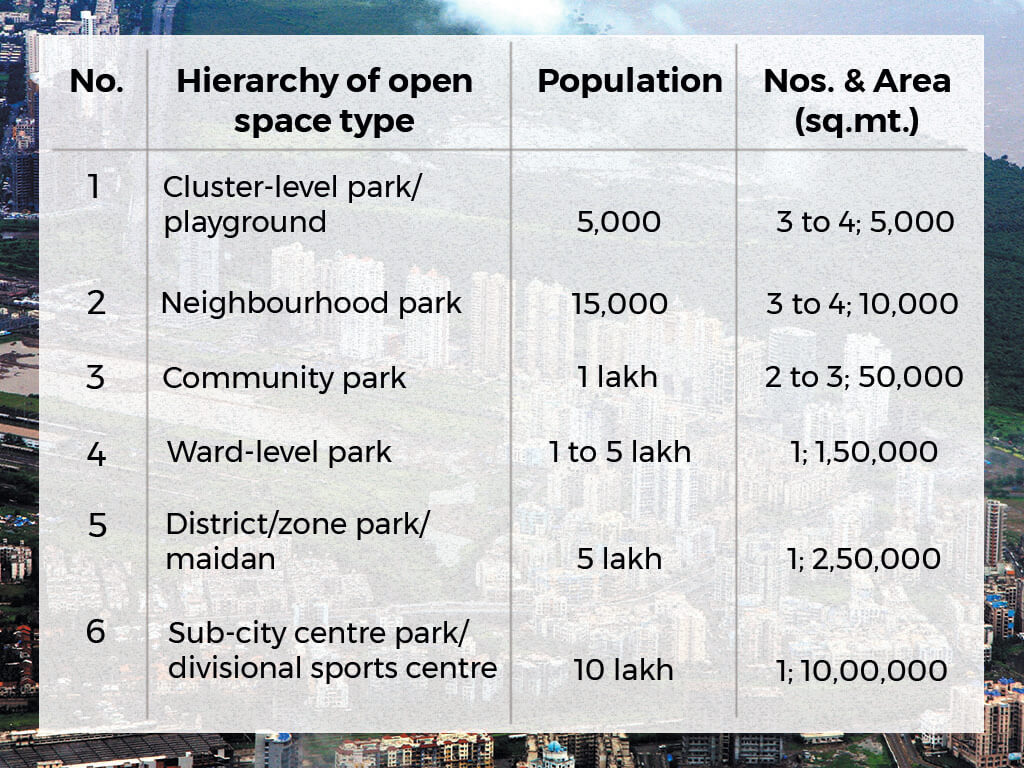

Open space hierarchy and location to serve the needs of all types of physical and mental wellness activities, and for all strata of the society is a crucial planning aspect. Navi Mumbai has been fortunate to have a greenfield at its disposal. The planning objectives were achieved by ensuring provision for open spaces in every block, understanding the land characteristics and contextualising it, and adopting some of the best practices of the world.

The implementation of the master plan was based on CIDCO’s model of monetisation of land for financing of public infrastructure service and improvement. The development of land for the purposes reserved in the master plan was largely dependent upon its characteristics and the practicality to develop it. The implementation saw the shifting of economic bases such as the APMC, part activities of the Mumbai Port Trust to the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT), and steel units.

However, the shifting of government offices and the CBD did not see the light of the day. This was partly due to the reluctance of a number of government bodies to shift base from Mumbai (often citing the need for proximity to the state legislature and Mumbai’s commercial centres), some resistance from people who had to commute to Navi Mumbai without the ease that Mumbai’s systems offered them, and because of the delay in building the MTHL. What succeeded in Navi Mumbai was the opening up of opportunities for the lower and middle-class people to purchase land and houses which included open spaces of various scales and types.

Photo: Prachi Merchant

The open spaces planning was likely the result of the liberty and free hand that the planners had, the greenfield area they planned for, the opportunity to put the best planning trends into practice, Mumbai, and the strategy to leave out the non-lucrative and non- profitable plots as open spaces. While the first two helped in proposing hierarchy of open spaces and linkages, ensuring a high per capita index of open space per person, it was the the third aspect which formed the context and gave a unique character to the open spaces of Navi Mumbai. For example, the rock gardens of Nerul and Belapur, the jewel of Navi Mumbai of Seawoods Darave along the marshy land, the highly contoured land as Urban Haat and Mango garden, and so on.

A quantitative analysis indicates that the open space planning not only fulfils the prescribed size standards but also meets the hierarchy of the spaces, ensuring its ample provision, accessibility and catering to all kinds of recreational needs of Navi Mumbai.[7]

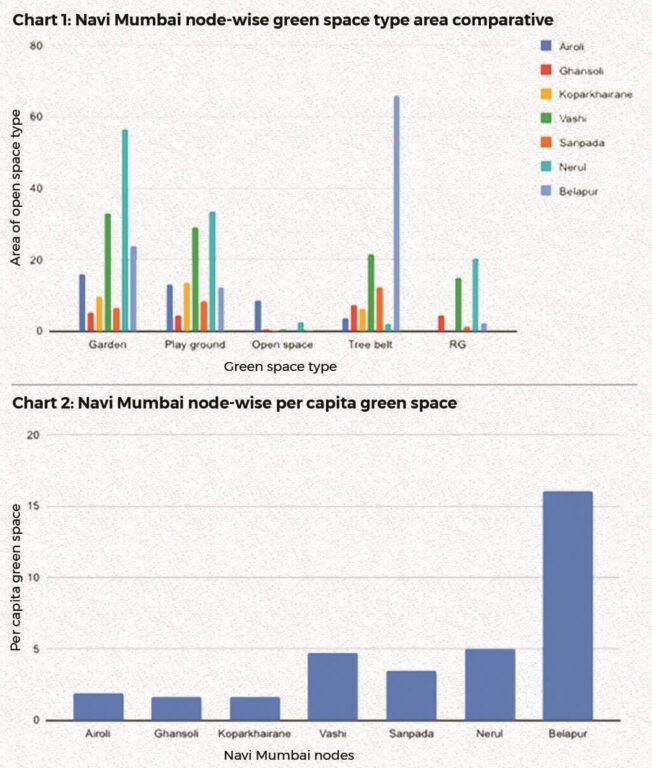

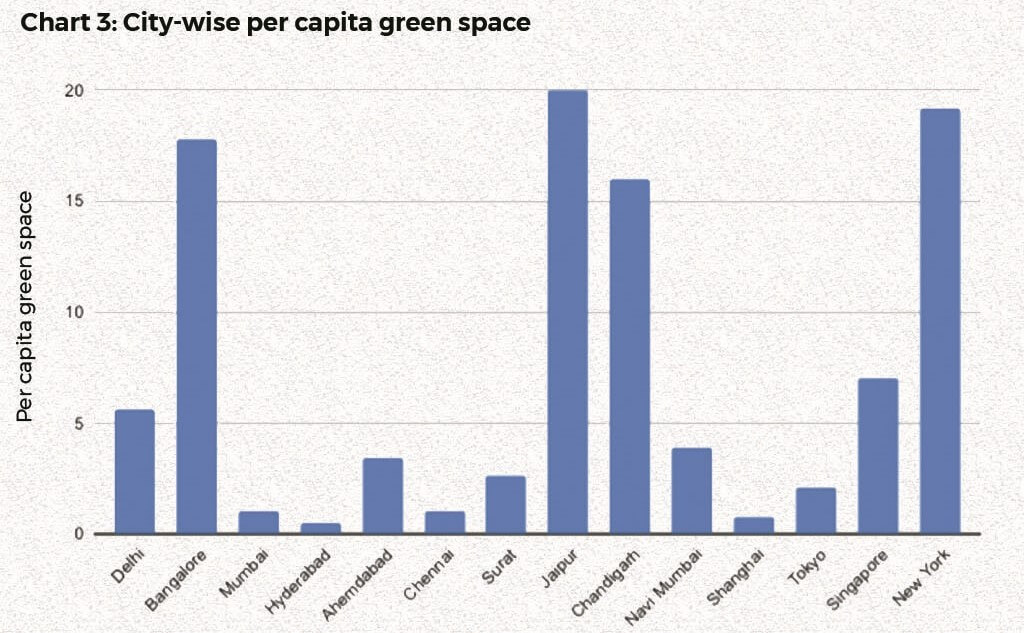

The charts below show Navi Mumbai’s green status at the nodal, national and international levels. Chart 1 indicates the provision of gardens, playgrounds, recreation grounds, tree belt and open spaces for each node of Navi Mumbai including its percentage of housing provision or natural land characteristics. For example, Nerul has the highest garden and recreational ground provision to cater to its high residential population. Chart 2 shows the per capita green space provision at nodal level within Navi Mumbai. For example, the Belapur node has the highest green provisions which is due to the high tree belt coverage besides the planned green space provision.

Chart 3 (above) shows Navi Mumbai’s position of per capita green space in comparison to the national and international cities. The new city across the Mumbai harbour stands at 3.95 square metres per person, which is higher than most of the Indian cities; it is similar to Ahmedabad, higher than Tokyo though lesser than Delhi and Singapore.[8][9][10]

The qualitative analysis and lived experiences of people over the decades confirm the green space availability and accessibility through connectors within a node and with other sectors too, around the water bodies, green buffer areas along the nallas, lakes, catchment areas, treebelt, valley parks, hills, and through undulated lands making the walking experience in most areas of the city a sheer joy.

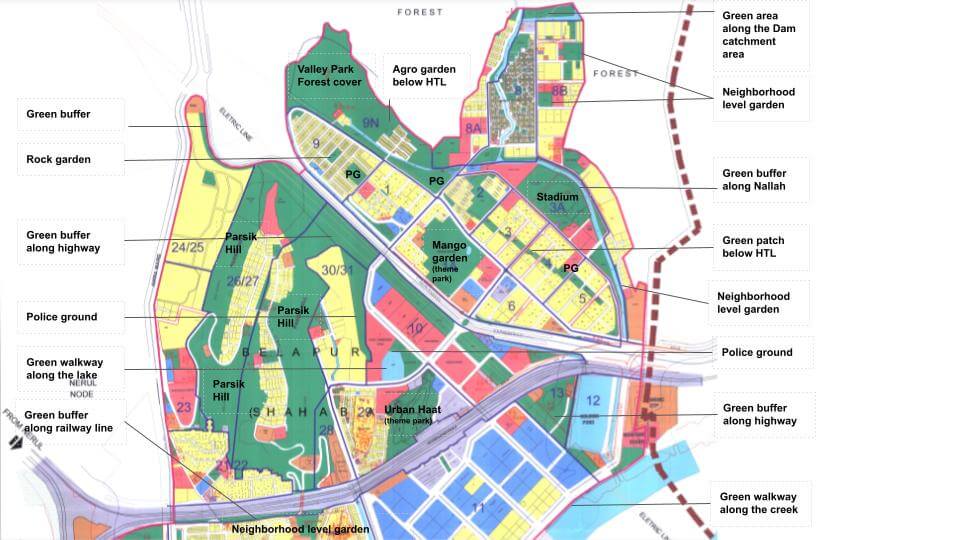

An example of the Belapur node as illustrated below demonstrates the qualitative and quantitative status of green spaces. A similar provision is made in the other nodes. The hierarchy of open and green spaces is evident in this plan. At the neighbourhood level, there is a provision of adequate gardens, promenades, parks, playgrounds of schools (PES ground, Bharati Vidyapeeth and Sunil Gavaskar Maidan), connecting lanes lined with greenery, greening of the land below high tension wires, and so on. At the node level, large parks (Mango Garden), lakeside, dam catchment area and creekside green walkways. This is followed by the Valley Park forest side treeline, Rajiv Gandhi Maidan and stadium accessed by the entire Navi Mumbai residents and the Urban Haat which is a regional cultural, open air recreational plus exhibition ground.

Source: NMMC Draft Development Plan report

Taking into account other regional-level provisions like the stadium the Ganpat Sheth Tandel Maidan and Yashvantrao Chavan Maidan at Nerul, Bhumiputra Maidan at Koparkhairane, and the DY Patil Stadium at Nerul where international tournaments in cricket and football are routinely held, it can be said that Navi Mumbai’s nodes have ample open spaces which have more or less stood the test of time. A variety of recreational spaces in Navi Mumbai has been provided through parks and gardens such as the Jewel of Navi Mumbai at Seawoods, Nisarg Udyan at Koparkhairane, Central Park at Ghansoli, mini seashores at Vashi and Airoli, the Wonder’s Park at Nerul, and the Amusement park at Kopri-Vashi.

The lessons for way forward

The planning and development of open spaces in Navi Mumbai offers a template for other cities. An element of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)[11] 11.7 is having sufficient public space which allows cities and regions to function efficiently and equitably as it gives opportunities to people. Access to open public space improves the quality of life of a citizen and prepares the city against the flood-like situation. The provision of open space for recreational and physical activities also reflects in the social and mental well being forming one of the most crucial parameters of the Liveability index of a city.[12]

Photo: Prachi Merchant

Navi Mumbai meets these parameters well and its green open spaces in each of the planned nodes are a major contributor to the social well-being of people who live and work there. It could be said that the open space provision in Navi Mumbai has also been a successful and efficient climate-resilient tool in reducing the Urban Heat Island effect created by concrete, pavements and buildings. The green infrastructure addresses the stormwater management too. The green buffers and tree cover along roads, highways, water bodies or industrial belts boosts the cooling effect and reduces CO2 emissions, air pollution, and noise.

Each node ensures the provision of green open spaces through standard design principles and guidelines. The hierarchy and seamless nature meets the best practice parameters making it one of the key aspects to be considered for social well-being while planning other cities. Navi Mumbai’s open space planning can form the template or guideline for new town development, and learnings for existing cities in terms of increasing tree cover and establishing green and blue connectors as climate change mitigators.

The main purpose of building a twin city to decongest Mumbai city may not have met all the expectations that were envisaged by its master planners, but there is no denying that Navi Mumbai has been successfully developed as a city on the greenfield area across the Mumbai harbour; importantly, it has achieved the status of a green city with state-of-the-art infrastructure planning with an emphasis on and provision for open spaces. The lived and shared experiences of citizens confirm that the green and planned open spaces are a crucial factor for their environmental, social and physical well-being.

It is for professional planners and people to take the approach of the planning of Navi Mumnai in terms of housing, climate reselience, physical, social and, especially green infrastructure, in the time of climate change. The master plan and its implementation can be referred to as best practices by other cities for multiple planning aspects.

Prachi Merchant is an architect and urban planner with work experience ranging from planning, design, urban and rural planning research to heritage conservation and development. She leads a team of professionals for setting up the Mumbai Parking Authority at the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, is a member of its Advisory Committee on Gender, and has been a part of the revision of Draft Development Plan 2034 for Mumbai and the Mumbai Transformation Support Unit (MTSU). She practised architecture in various firms including as a partner at the Architecture Associates. She also teaches and has published research papers in national and international journals and forums.

Cover photo: Central Park in Kharghar, Navi Mumbai. Credit: Wikimedia Commons