Nikeita Saraf and Ankita Dhar Karmakar

Ishwar Singh, Rajwa, Rajasthan

Save Aravalli Movement

“Women who are MNREGA workers sit together after work and sing songs. These songs don’t come from a book; the women compose them, weaving in their sorrows, problems, and life’s circumstances into words and melodies. They sing about the rain and sun, they give voice to their troubles. Sometimes they address the government: “Humein kaam do, humari majdoori badhao (Give us work, increase our wages).” They speak to the sky, “He dhoop, thoda tham jaon, aur baadal baras pado. Humein baarish ki zarurat hai! (O sun, hold back a little and let the clouds burst, we need the rain).”

“Their pain is also present in these songs because the trees, mountains, animals and along with them, they themselves are also troubled by what’s happening. The irony is that these women are working to build a check dam but, right in front of that check dam, mining is taking place which is a major cause of all this suffering.”

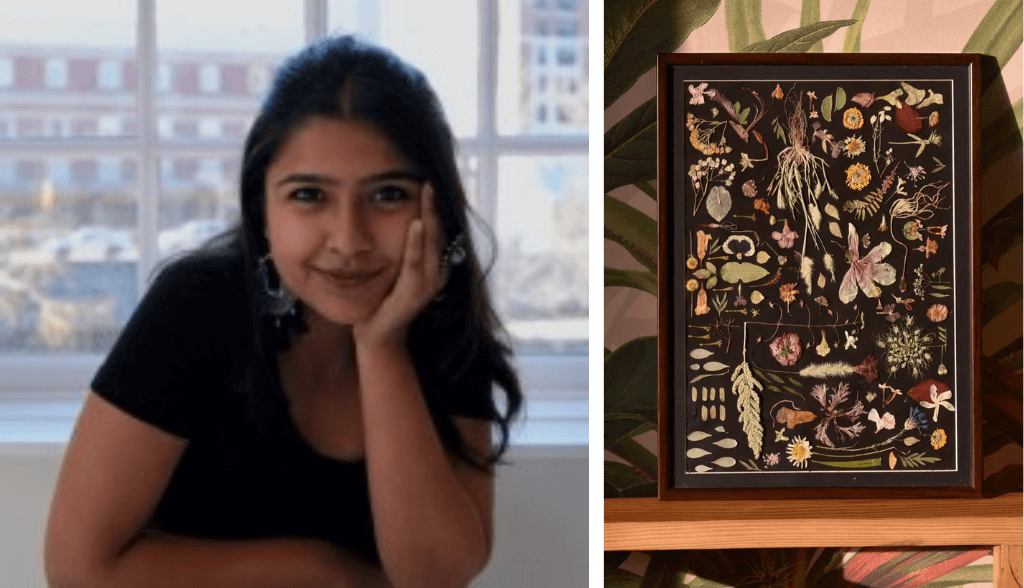

Kaanchi Chopra, Delhi

Artist and designer

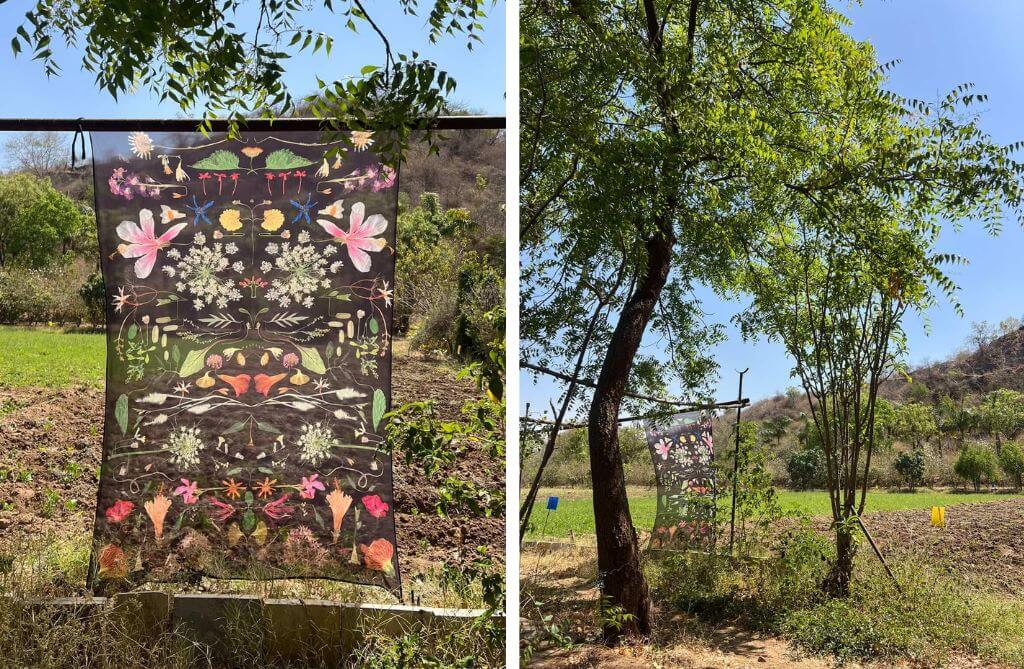

“For the Jaipur Art Week, I am working on a project on the ethnobotanical language of plants found in the Aravallis. There are nine panels — each 9.5 feet in diameter, 8 feet height, 9 metres in circumference – each showing different uses of the plants found in the Aravallis and used for natural dyeing, food and sustenance, pollination, herbal medicines and so on. The second is basically the composition I make and is printed 8 feet high.”

“I was born and raised in Delhi; the family moved to southwest Delhi three years ago which is on the outskirts and close to farmland. Air pollution is a personal issue because I grew up in West Delhi where the AQI is really bad and has minimal tree canopies. Growing up with no trees, we saw how hot summers could get and how pollution increased. Things are remarkably better now. I didn’t grow up with natural abundance around me but I found solace in plants. Then, I started photographing plants; I did not think of making plants my primary medium. But the more I learned by reading the works of Robin Wall Kimbrell, Vandana Shiva, Pradeep Kishan, the more I got involved. The first plant I collected was the white spider lily – a favourite. I realised these flowers are not just ornamental – they have embodied knowledge. They carry so much history.”

“One of the things you have to be careful about when foraging is to never take more than one or two pieces. There’s a beautiful quote by Robin Wall-Kimmerer in her book Braiding Sweetgrass –– whenever you forage, never pick up the first flower because it could be the last of its kind. I fear that 30 years from now, some of the species I foraged will exist in the herbarium I have made. This is from the lens of an artist- practitioner. But for communities who actively depend on them – this is survival, it’s medicinal, low-care health systems. Losing these species is a loss of knowledge and livelihood. As city people, we can empathise but we cannot ever truly understand what it means to entirely lose the land. That the Supreme Court stayed the earlier order means people’s fight for the Aravallis succeeded; the task is to keep that rage going.It’s a long battle but it’s nice to have the shimmer of hope.”

Madhura Ghane (Stage name Mahi G), 28

Kalyan, Mumbai

Artist/ Lyrics by @mahig_55

Music By @rapboss8055

Video by @vaibhav_nighut

“I belong to the Mahadev Koli Adivasi of Maharashtra. I have lived in Kalyan and have an engineering degree in electronics and telecommunications. I started writing poems in college. Back then, rap became popular because of Gully Boy. I felt I should try it. The farmers’ protest was going on near Delhi. I wrote one and posted it on Instagram. My friends liked it; I got confidence. Then, during Covid-19 lockdown, my family and I went to our village, Waranghushi, in Ahmednagar where I saw struggles and happiness of the people there, and wrote a rap song called Jungle cha Raja (King of the Jungle). On social media, I met Rapboss, a well-known Marathi rapper and a music producer. We shaped the song together, I recorded it his studio under his production RFM Studios in Pune, and shot the video in my village. I shot in my grandmother’s saree. I wanted to tell my story to the people.”

“The intention behind the Aravalli rap was that there are a lot of environmental crises in the world and people should know about them. I thought I should write a song since I have the ability to write. I wrote some parts in the local Rajasthani language, Marwari, so that it can reach more people there. I feel that the youth and the people who are going to be affected by this should be sensitive in terms of environmental issues or other issues as well. They should have the space and freedom to raise their voices.”

“This song comes from what we are witnessing across the country. Hasdeo. Uttarakhand. Great Nicobar. And now the Aravallis. Different places, same pattern.

Decisions taken by governments, corporations and people in power are redefining forests, hills and land, not for protection, but for profit. Forests are cleared and voices of local communities are ignored. The Aravallis is not just a mountain range; it is water, climate balance, biodiversity and life. What is happening to Aravalli today – and to forests across India — is not development. It is destruction in the name of development. This track is a voice of resistance.”

The song starts with the visuals and screeching noises of the Aravallis hills being mined. It transcends into a call for action to speak up against the court orders that allow for a centuries old mountain range to be cut down for the benefit of a few. Mahi, through her lyrics, calls out the violence hidden in the language of development. Her words echo anger, urgency, and a deeply personal loss as the land is handed over to those who see profit over people. In Mahi’s hands, rap music has become a documentation, protest, and memory. The song has 4.9K views and over 700 likes on YouTube and has been shared and reposted multiple times.

Vijay Dhasmana, The Rewilders,[1] instrumental in restoring the Aravalli Biodiversity Park in Gurgaon

Photo: iamgurgaon website

“I have been working in the ecological restoration space and have restored degraded land such as the mined landscape in the Aravallis. One of the sites is a 380-acre site earlier used for mining. The rocks were removed and then we transformed it into the Aravalli Biodiversity Park in Gurugram, Haryana. This started in 2010. Now, there are mainly 10 projects in Gurugram – in Aravalli Nagar, Sikandarpur, Ghata Band, Bhairampur Band, Chakrapur Wazirabad Band, Badshahpur Forest Corridor. It is a huge amount of work.”

“The Aravallis are important for north India and so its conservation is important for groundwater recharge, and preserving biodiversity. They are crucial in regulating the water crisis and air pollution crisis in the city – groundwater is depleting at 5 feet per year as the city pumps out 300 percent more groundwater than it recharges; the Biodiversity Park recharges over 320 million (32 crores) litres of water annually. Not only this, the Centre for Environmental Research and Education (CERE) undertook a study of the Park in 2018 and found that the park supplies 7.07 percent of the oxygen requirement for Delhi NCR.”

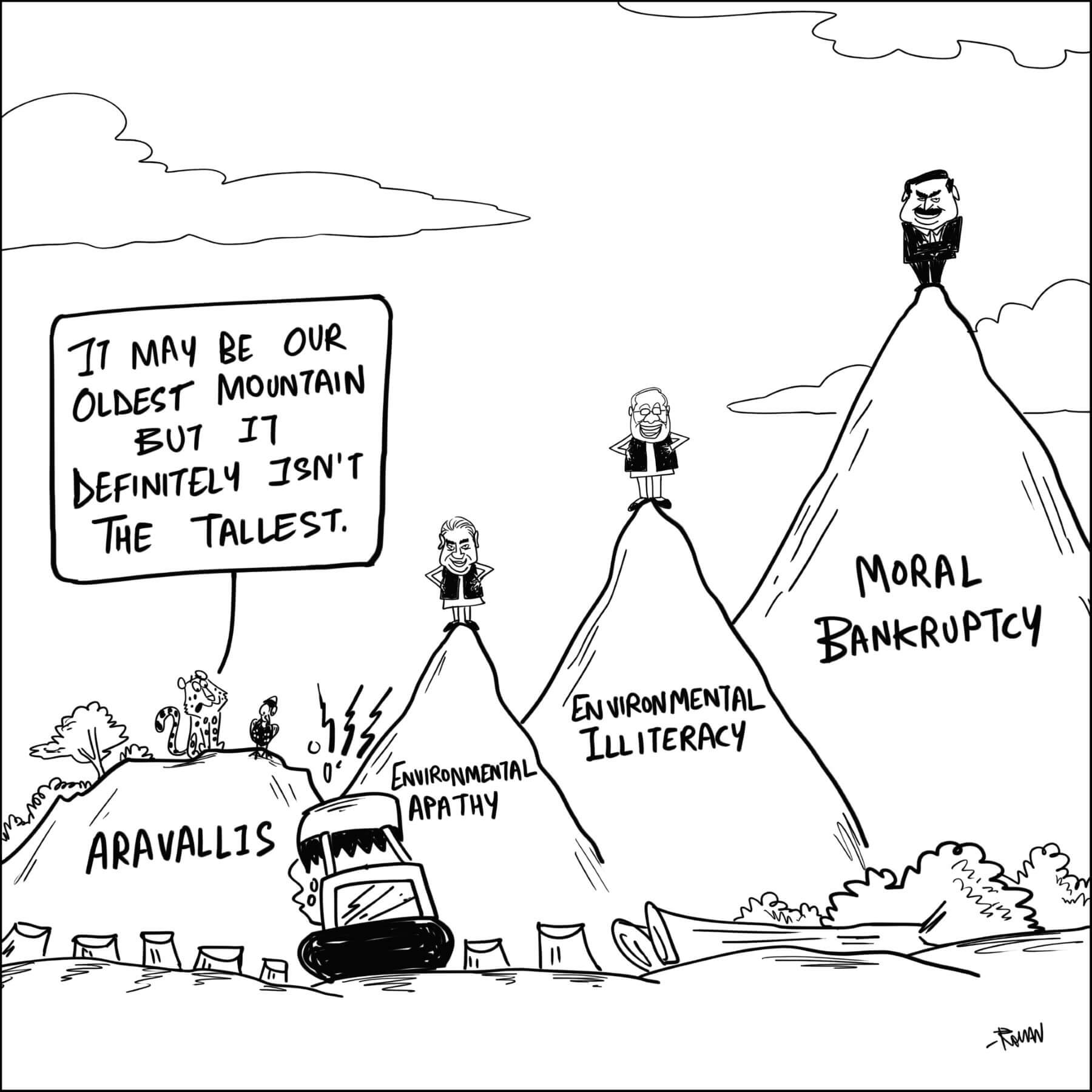

Rohan Chakravarty

Environmental cartoonist and illustrator

Green humour [2]

Dr Kumpal Walia, Gurugram

Retired teacher of Biology

“We have to bring people together so that the government understands the importance of the Aravallis which have been protecting us for so many years. Now, it’s our turn to protect it. That’s why I am with the Aravalli Bachao Abhiyan. We are doing our part. If we keep cutting trees in the name of development, then what is the point of such development? Delhi is already struggling with its severe Air Quality Index. We are destroying a natural purifier in the name of development. How long will we keep breathing polluted air?”

Rahul Khera, Gurugram

Founder of ‘Balancing Bits’

“The Aravallis are the few last green patches we have left in the Delhi-NCR region that we must conserve. Not just for us but for the biodiversity and other species around us. Otherwise, it will just be us living on this planet.”

POEM

वो शूलों की एक शैया है,

वो शुष्क है, पर वो थार नहीं।

वो कद में थोड़ा छोटा है,

भरपूर है वो, विस्तार नहीं।

न उद्द्गम है वो गंगा का,

न वीर हिमालय की चोटी।

पर घर है वो, वो आँगन है,

किलकारी उसमें भी होती।

चलती कुदाल, टूटे पत्थर,

सड़कों पर पहिये बहते हैं।

कद सौ हो, चाहे सत्तर हो,

ये कटते-छटते रहते हैं।

सरकार की दृष्टि हो खोटी,

तो कानून भी अंधे रहते हैं।

और राष्ट्र-हितों के झंडे में,

जब लिपटे धंधे रहते हैं।

दशा बदलने के प्रण जब,

बस दिशा बदलते रहते हैं|

इनका भी नाम बदल दो तुम,

इन्हें क्यों अरावली कहते हैं?

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS), she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Multimedia Journalist and Social Media in-charge in Question of Cities, has reported and written at the intersection of gender, cities, and human rights, among other themes. Her work has been featured in several digital publications, national and international. She is the recipient of the 4th South Asia Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity and the 14th Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from Ambedkar University, New Delhi.