“I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.”

Those are words by Langston Hughes in The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Rivers have been part of our shared history, interwoven into the very fabric of our worlds, our mythology, our stories. “Well, a river runs through each of us, and a river runs through human history. The first cities grew on the banks of rivers. I think of Uruk in Mesopotamia, which literally means ‘the land between two rivers,’ between the Tigris and the Euphrates,” says Robert Macfarlane, British writer on landscape and nature, in an interview with Emergence Magazine.

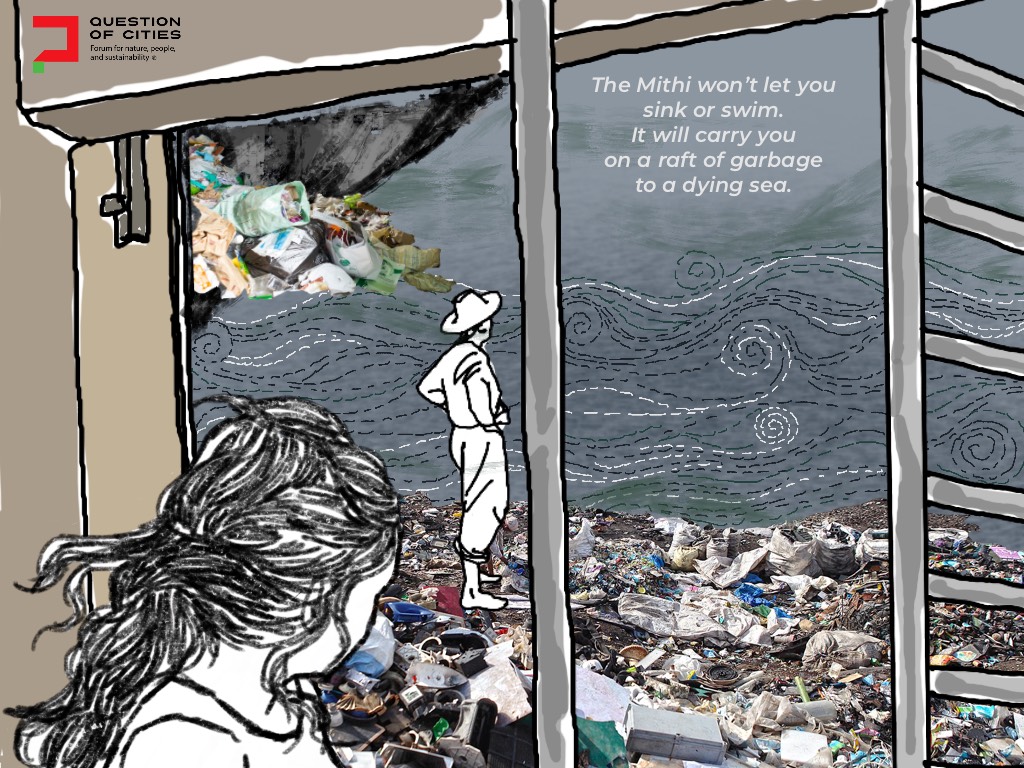

When I look at the rivers in my own city of Mumbai, reduced to gutters over the years, I try to think about what it might have been earlier? Did the Mithi have a time of glory?

When we pass by the Mithi river at Mahim creek in a Mumbai local, I close my eyes and try to imagine. I imagine a city where this river is clear and flowing. I hear the soothing sound of running water. There are trees on the banks, and a beautiful old bridge across it. People sit on the banks under parasols. Picnic baskets with sandwiches, samosas and nimbu paani dot the riverside. Kids frolic, play and leap into the water. But soon enough, the stink rising from the infected river wakes me from my reverie.

The city’s legendary poet Eunice De Souza said in her poem Mithi:

“The Mithi won’t let you

sink or swim.

It will carry you

on a raft of garbage

to a dying sea.”

We worship rivers, we carry rivers

Recently, while scrolling on Instagram, I chanced upon a video of people offering paan and flowers to a river as it flowed into their village. They prayed to the river, stood in obeisance, and bowed down to it. Research told me it was the river Cauvery, and the festival Aadi Perukku, a time when people welcome the river into their village.

This sentiment of kinship and worship is also echoed in Natalie Diaz’s poem The First Water is Body. It begins with the line “The Colorado River is the most endangered river in the United States—also, it is a part of my body.” She goes on to enumerate the many ways in which the river and the body are not just alike but one. She says, “I carry the river, it is who I am”.

It makes one wonder: When did we stop carrying the river? When did we separate ourselves from it? A river in a city also holds urban legends, history, the lives of people led along the banks. “In English there is no verb to river. But what could be more of a verb than a river,” reflects Macfarlane in his latest book Is A River Alive?

We are rapidly losing our rivers in most cities in India (and the world). We haven’t thought about what might become of us when the rivers rebel or die. If the river is a ghost, am I, asks Diaz in her poem. I wonder what the Mithi is, if not a ghost of a river. Then are we far away from the predicament?

We often speak of people feeling a deep sense of isolation. In this context, the question presents itself: Is it because we have divorced ourselves from all the life we once belonged to? All the life that thrived around us – the rivers, the currents, the fish, the frogs, the snakes, the stories. All this life weaving a wonder-full world? Far away from this, we now belong to concrete, plastic and blue screens. We scroll and like videos of frogs. We read Basho and Dungy. We search for ways to make sense of the emptiness that dominates our lives. We try to find the words that help us make sense of our experience.

We wonder what the poets think. So, for Question of Cities, we invited poets to share their reflecting, questing, grieving and rebelling poems on rivers and cities. Athira Unni and Ishan Sadwelkar wrote verse exclusively for us while Aswin Vijayan, Kinjal Sethia and Pervin Saket shared their words for this curation. The poets wrote tiny texts for their poems, offering contexts and cues. And Nikeita Saraf did the illustrations.

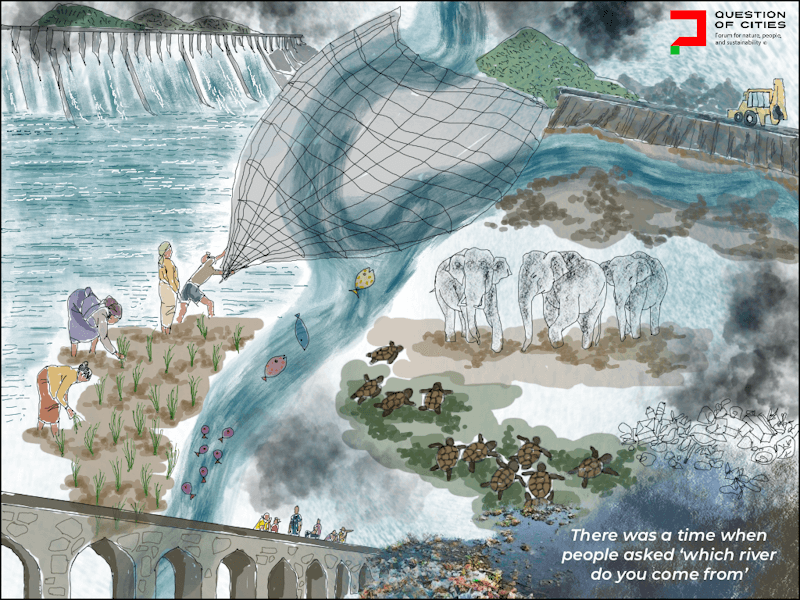

Ishan Sadwelkar takes us back in time to when rivers actually served as addresses, when people were asked ‘which river do you come from’, in this poem.

Searching for a Confluence at Sangamwadi by Ishan Sadwelkar

I await lost flamingoes, I preen dead carps –

stones no longer temples, dives no longer deep,

forage suffocates under concrete, sunken idols

and natives dismember together; a long whip

of a laundromat punishes rocks for being clots.

Armies neighed, spies swam. Before, nomads

sowed paddies, teals wintered, and even before,

elephants and aurochs waded through, at first

there was only this river; she had futures.

A river was more than a city’s crevice, a mother

to all things that come later, nets domed over suns

and landed on crabs, at times gems – they sprang

empires and ended some; she drank every decline.

Today garbage crocodiles downstream, no

air left for turtles, hamlets rubble into canals,

misery landfills onto her shoulders, sand veins

into ambitions less extraordinary such as roads, ceilings.

There was a time when people asked ‘which river

do you come from’, instead of names; at the fort

Shrimant promised, ‘from your water I’ll plant my flag

on northern thrones, my horses will bridge every bank’.

Now hardly a ghost left to whine with, a fake

commerce crowds over her chest, that horse

who centuries ago galloped across, never

quenched thirst here again; today his stride

is sewered into a flood of suburbs.

Shrimant is an alternate title for Peshwa Bajirao I, the prime minister of the Maratha Empire between 1720-1740 who remained undefeated across 40 battles and expanded the confederacy from the Deccan towards the north and south of present-day India, leaving his mark as one of the finest military generals of the corresponding early modern period; his political base was in Pune at the banks of the Mula-Mutha river. Known for his innovative use of cavalry, sharp military tactics with rapid movements, he spent most of his wartime life on a horse, crossing various rivers, and he eventually passed away on the banks of the Narmada while returning from a campaign.

About the poem

The poem is an attempt to biography the ancient Mula-Mutha in Pune, a city that grew and prospered on its banks. They originate as the Mula and Mutha in the Western Ghats. Today, the river is reduced to hardly a fraction of its former glory. One studies the impact of years of pollution, loss of natural, architectural and intangible heritage that the river has endured. From prehistoric, to historic, to modern times, the river has seen a dramatic decline as narrated through the poem.

As is the case with most rivers and wetlands in India, issues such as poor urban planning, sewage, dumping, vanishing of species and the overall degradation of ecosystems is unfortunately apparent. But it is also important to understand what once was, in history there are cues to how we might imagine a restored, clean river that was once the lifeline of civilisation, a thriving sphere of commerce, indigenous prosperity and natural abundance, and maybe some inspiration to remedy our wrongs.

*****

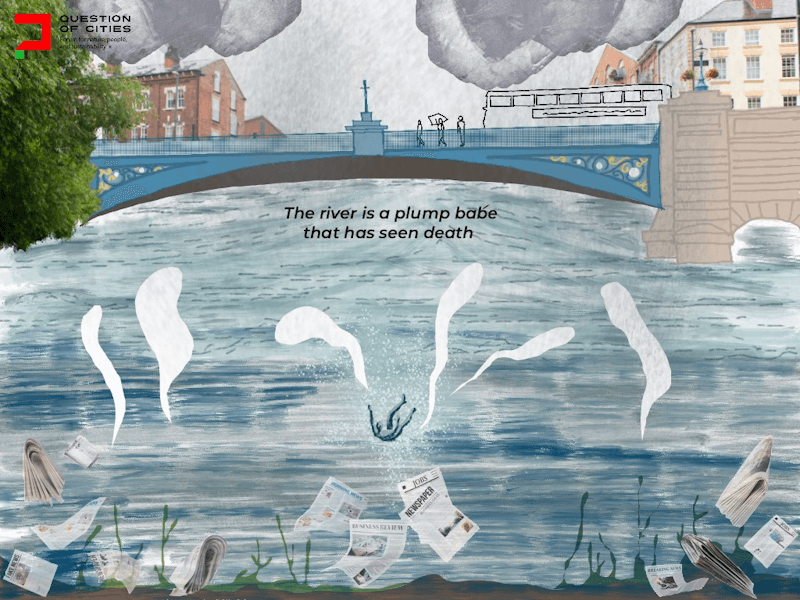

On the Banks of Aire by Athira Unni

While seated at Mumtaz

the waters of Aire

muscle its way through

each side of the salmon,

pink and serrated

on my neighbor’s plate.

The restaurant sits perched

beside the fish-silver river,

its glass mouths filled with boats.

England is a land of hedges.

Beavers build dams, the waters

don’t stop. River is refuge.

David Oluwale, all those years ago

leaped into these turgid

waters, fleeing the cops.

Ex-stowaway, engineer, homeless

mad man. Lived on scraps. His face

sank into the laps of the river druids.

It is said the waters stink for days

when a body sinks. Urban legend.

A string of plums in sharp vinegar.

The taste of chicken is raw

on my tongue. The river is a

plump babe that has seen death.

About the poem

While living in Leeds, I came to know about the tragic life and death of David Oluwale, a Nigerian man who had come to England as a stowaway in a ship and lived on the streets of the city for years. He was hounded to death by the cops and he died in the river Aire. I had seen the river up close many times but the urban legend of Oluwale made me see it in a new light. It is not as noteworthy as the death of Virginia Woolf in the River Ouse perhaps but Oluwale’s drowning in the river speaks to how he became in essence one with the landscape of Yorkshire.

The city of Leeds remembers Oluwale even today and the river flows through the city carrying memories and stories such as this even as beavers build dams and boats ply on it with renewed vigour every day. Such stories not only make the river timeless, a storied legend, but renders it the aspect of being a character in the story itself. The river is not just an innocent bystander, it has known pain and death up close, a dark and formidable truth.

*****

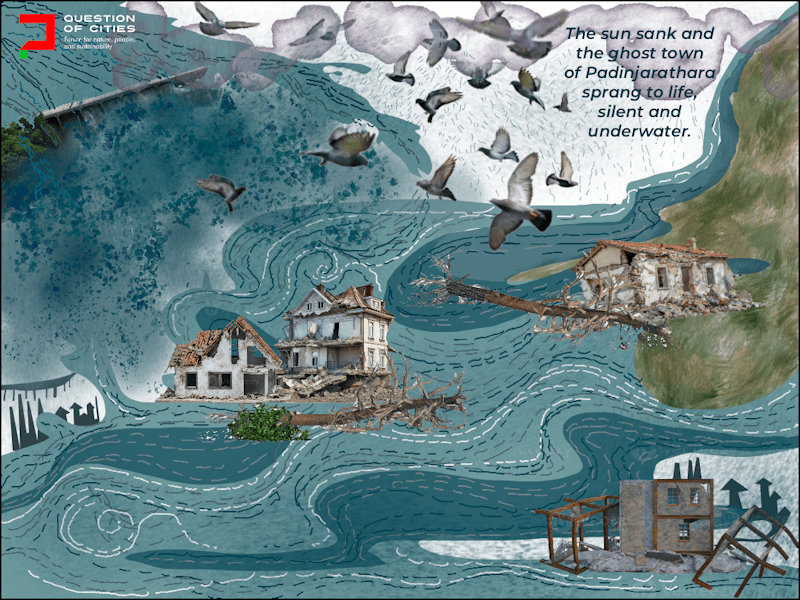

“Do you think the water will forget what we have done, what we continue to do?” pondered Natalie Diaz. If water has memory, then what will the rivers remember? Will they remember the plastic? Will they remember the flood? Aswin Vijayan takes us to picturesque Wayanad, a haven for tourists, but what lies on the other side of the hills?

Padinjarathara by Aswin Vijayan

Here, this is our Atlantis, the boy did not say.

He spoke with a certain lilt in his voice, with the slant

of someone on whose tongue the tongue doesn’t rest easy.

We were on top of the small hillock on which the resort

had just come up and the slope ran straight into Karlad lake.

There we were, looking out at another body of water.

This was no Atlantis but a trolley problem. Ten houses

drowned for the sake of 20000 families irrigated

and many more electrified. This little part of town

underwater, rusting. And the dam, named after Bana,

sun of Bali, swallowed up the whole region sinking

walls, roofs, gardens, trees, and fences as they stood.

The birds saw the floodwater rushing—anticipating

a landslide 20 years ahead—and flew to nearby hills.

A few hills away, I sat reading a book, as a kite failed

to fly over my head. A leech hung from the inside

of my left foot, drinking blood. I waited till it had its fill

and eventually fell away. The sun sank and the ghost town

of Padinjarathara sprang to life, silent and underwater.

About the poem

What are we willing to sacrifice for comfort? Just like individuals, cities and nations are constantly faced with this question. More often than not, the choice made is the less sustainable, short-term ones that maximize profit at the cost of the most vulnerable. An encounter with the story of such a trade-off led to the making of this poem.

*****

The poem by Kinjal Sethia, Side-tracked, takes us to Goa and the mining around the Mandovi river and the destruction of Mollem forest.

Side-tracked by Kinjal Sethia

A colossal evergreen crashed into darkness. Herons gone from Vhoddlem lake and men struck to the ground by metallic greed. Women stuck on trees. Again. Mollem trampled to slap on rails, power lines and concrete. Primaeval roars. Mangroves and old Portuguese house spade in their roots. No one wants to move, and is pushed aside. Shell windows smirk with broken piano teeth. Balustrades limb out to fence in their families. The hornbills, drongos, orioles golden the light streaming through proud crowns, and flicker when their shadows fall on parched grounds. The Malabar tree nymph leaves the window before all the teeth fall. It’s black on muslin white surrendering to the call of the saw drill. It flies past the beginning of Mandovi and out of Mollem before the khazans silt over. Who can say that our bodies are not coloured by the melanin translucence, by the shroud of its varnish? Who can tell the birds to check their wingspans, to make sure their flights don’t damage fibrous rail lines? Who can tell me I don’t belong? When the Malabar squirrel jumps arboreal, who will call it back to the mammoth green? Who will remind us this is home?

About the poem

Rivers have personalities. The lethargic Ganga at Haridwar, the elusive Saraswati at Mana, the expansive elegance of Shyok in the Nubra valley, the fateful honesty of Mula-Mutha in Pune, the shimmering Mandovi under the Goan sun; all the rivers that I have ever crossed remain friends with me. And when a friend is in trouble, they stay on your mind even amidst the prosaic routine of your day. So while I pursue a good life away from the place of my childhood, it rankles me that 500 kilometres away the Mandovi was hurt while rampant mining continues; that even in my city, a river is being used to dump the products of human greed.

*****

The lines “who will remind us this is home?” spring out from Sethia’s poem and make a home in the reader’s mind. It is such a poignant way to end the poem. We are so accustomed to thinking of our apartment, our building, our neighbourhood as home, we have forgotten that this earth with all its creatures strange and mundane, with its rivers, flowing and guttered is all home.

Poetry may not be able to change the world, but it can certainly bear witness. It can hold the river in the palm of its hands and look at it, really look at it. In her poem Too Much Faith, Pervin Saket grapples with what words could do in the face of the climate crisis.

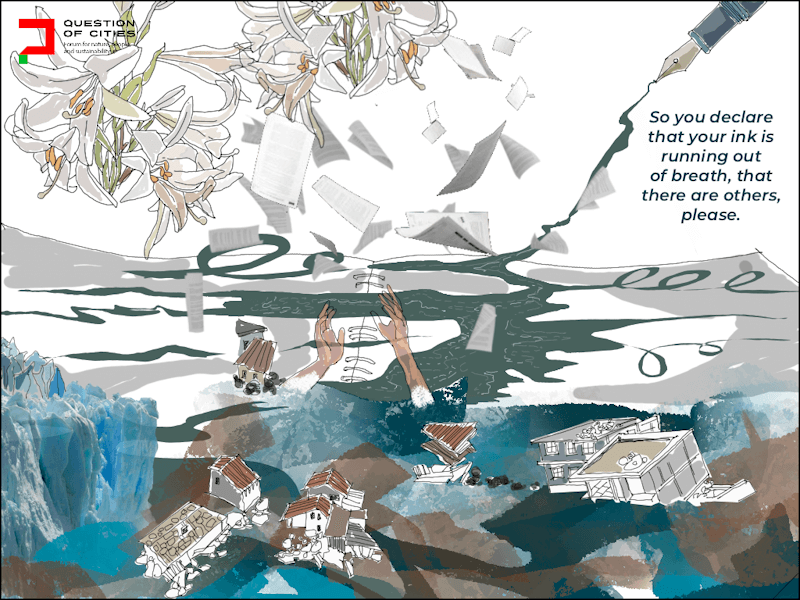

Too Much Faith by Pervin Saket

Suppose you decide to write

a poem about the coming of spring.

You consider little things like the lilies

near the creek you pretend is a river,

but you’re done with garnish and gimmick.

You need a verse with such truth

it can reverse melting glaciers and freezing

sanctions, resurrect forests into surprised green.

So you begin to write about the promise

of a new age, but the slogans of the young

suggest they’ve been the old of another time.

The page smells of soot and metal and 1984.

You decide to work your way towards

the quiet treasures of delta and dirt,

but you need to stay away from

unchecked mining, at least in this poem.

You might start a ghazal for the Mitthi,

or lush, eager odes to tadpoles,

but your lines turn arid, your pauses, nettles.

You once believed that art can heal

but your fingers are now calloused.

So you declare that your ink is running out

of breath, that there are others, please.

And yet, when once again the summer

is too late, too long, too much

and the world is drooping on its own axis

and this time your grandmother’s

village is submerged, your thatched childhood

swept away, you find yourself reaching for this prana

of twenty-six letters, scattering vowels

for seeds, hoping you haven’t placed

too much faith

in words.

About the poem

For me, words have never been abstract. They do things — they carry, interrogate, connect, employ, remind, insist. But every once in a while, when the systems of the world get too overpowering, language feels broken. Or tired. Fortunately, during such moments, we have poems such as Kim Addonizio’s Solace which starts with:

Once when my coat

was too thin, and one torn

pocket was all I had left of

a great love, I found

a blue canto

that calmed me.

I wrote Too Much Faith as an exploration of this nourishing but frustrating relationship with language. The deeply-lived belief that words do something, and the despair that they cannot do everything. This poem doesn’t have easy answers to our complicated climate crisis. But it does, I hope, return to language to name what’s broken, imagine what’s possible, and stay with what hurts long enough to act. It is ironic and strangely apt that in contextualising this poem, I have leaned on another. But that feels like the most honest gesture of all, one voice building on another, creating a chorus that insists on being heard.

*****

I would like to end with circling back to Diaz “The water we drink, like the air we breathe, is not a part of our body but is our body. What we do to one—to the body, to the water—we do to the other,” she says in First Body is Water. What we have done to our rivers might be a reflection of what we have done to the world and to one another. It is a sad reality but in there is a nugget of hope too, for if we change what we are doing to our rivers, it might change what we do to each other, it might change how to inhabit the world.

Yashasvi Vachhani is a poet, editor, and educator. She facilitates creative writing and reading programmes for children across ages. Her work has been featured in SWWIM Miami, Of Brave Hearts and Dry Tongues, and Singapore Unbound. She is an editor at The Bombay Literary Magazine, co-founder of The Osmosis Poetry Prize and founder editor of Tiffin Box Review.

Ishan Sadwelkar is a filmmaker, writer, and researcher who has explored and extensively written about the city. His written work has featured in national publications. An assistant director on films and a documentary filmmaker, he combines his passion for studying culture, heritage, food with his great love of nature.

Athira Unni is a researcher and writer living in California. Her poetry has appeared in a number of online and print journals. Her first book of poems “Gaea and Other Poems” was published in 2020. She is fascinated by octopuses and enjoys a good cup of tea.

Aswin Vijayan is the author of the chapbook Under the Handstand Statue Man. He teaches literature at Zamorin’s Guruvayurappan College in Calicut and holds an MA in Poetry from the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University Belfast. In 2022, he received the Toto Award for Creative Writing.

Kinjal Sethia is a writer based in Pune. Her work has been published in nether Quarterly, Gulmohar Quarterly, In Parentheses, Bangalore Review, Tahoma Literary Review, Marrow Magazine, Singapore Unbound, Out of Print among other places. She is a Fiction Editor at The Bombay Literary Magazine and a co-founder of The Osmosis Poetry Prize. She is the recipient of The Vijay Nambisan Poetry Fellowship for 2025.

Pervin Saket was a 2024 writer-in-residence at the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. She has served as the Poetry Editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine and the curator of Literature at the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, Mumbai. Her books include the novel ‘Urmila’, the poetry collection ‘A Tinge of Turmeric’; and a series of 10 landmark biographies-in-verse for children.