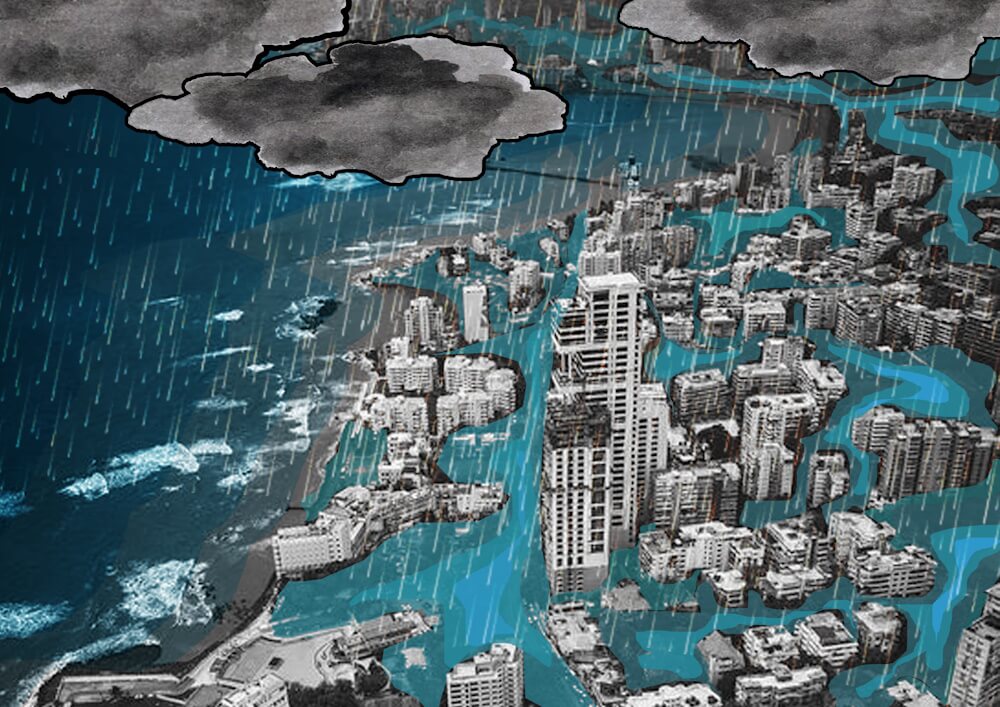

Monsoons strike Mumbai annually, submerging parts of the city in water from early June to mid-September. As the monsoon season approaches, efforts to repair old roads and launch new reclamation projects intensify in anticipation of the heavy rains. These torrential downpours, coupled with the changing land-water dynamics and the unpredictability of climate change, underscore Mumbai’s persistent drainage problem.

It has been nearly two decades since the catastrophic floods of July 2005, which caused enormous loss of life – nearly 1,100 died – and damage to property. The floods served as a stark reminder of Mumbai’s declining resilience in water management, primarily due to its disregard for maintaining its natural absorptive landscapes. Despite the passage of time, Mumbai’s planning models have failed to integrate environmental considerations into their decision-making framework.

As a result, the city’s capacity to manage water has progressively weakened. This persistent vulnerability highlights the critical need for Mumbai to reassess its planning methodology and water management strategies. The city’s continued reliance on land reclamation for development and expansion raises pressing concerns about how much longer this can be sustained without addressing the fundamental ecological and sustainability issues. Can the sponge city concept save the city – or at least help reduce the runoff?

Sponge city: A vision for Mumbai’s future

Historically, Mumbai was a vibrant mosaic of wetlands, mangroves, and tidal flats. These ecosystems maintained ecological balance and managed the flow of water, supporting a diverse range of wildlife and protecting against coastal erosion and storm surges. However, the present-day Mumbai, carved from these watery origins, presents a stark division between land and sea, leaving little room for the natural estuarine environment that once was. This transformation has greatly compromised the city’s ability to handle flood disasters.

The catastrophic flood of July 26, 2005, highlighted the dire consequences of de-vegetation and poor urban planning. The Mithi River, a crucial natural drainage channel, was overwhelmed due to pollution and encroachment, demonstrating the urgent need to restore and preserve Mumbai’s blue-green infrastructure, or water bodies and forest or tree cover. Architect Anuradha Mathur, in her seminal book Soak, emphasised the necessity of embracing the city’s aqueous terrain. She advocates for design approaches that retain monsoon waters instead of channeling them away, highlighting the potential for Mumbai to become a sponge city—a city that naturally absorbs and manages water.

A sponge city is designed to manage water sustainably. Cities as diverse as Shanghai[1], New York[2] and Cardiff[3] are embracing their “sponginess” through inner-city gardens, improved river drainage and plant-edged sidewalks, says this report.[4] Such a city absorbs rainwater and emphasises natural stormwater management infrastructure, reducing the runoff of water, and helps flood mitigation. The concept represents a transformative approach to urban planning that leverages natural and engineered solutions to enhance the city’s resilience.

Research by global design firm Arup and the World Economic Forum[5] shows that natural methods to absorb urban water are about 50 percent more affordable and 28 percent more effective than human-made solutions. By embracing the sponge city concept, Mumbai can transform into a city that naturally absorbs water, enhancing urban livability and resilience against climate change. The push for a sponge city is based on the conviction that the climate crisis requires us to broaden our urban imagination and reimagine urbanisation in the context of a flagrant disrespect towards the natural environment.

Mumbai’s untapped potential

The city still has about 140 square kilometres of natural areas[6] though its topography has vastly changed from the time it was seven islands. With landfilling or reclamation to make more land available for development, the relationship between land and water transformed across the city – the city as estuary all but disappeared, coastline and contours of the city changed, hills and green cover diminished, streams turned into drains, and landscape was perceived as small dispersed pockets of constructed parks and beaches.

The city still possesses blue-green wealth – many types of water bodies and green cover – that can be converted into sponge infrastructure. Despite significant reductions over the past few decades due to rampant urbanisation, key elements remain. Salsette Island, which Mumbai sits on, is endowed with rich natural infrastructure. This includes the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, a substantial urban forest, although it is not fully accessible to the public. The Mithi River and other riverine systems that include Dahisar, Poisar and Oshiwara rivers, albeit heavily polluted and encroached upon, represent river networks that could be revitalised.

Historically, the island’s numerous lakes, marshes, and salt pans created a landscape that absorbed monsoon rains and mitigated floods. The complex waterway system made up of numerous creeks, rivers and canals, characterised it; breaking the hard border between land and sea, water and land coexist in wide patches of wetlands and mangroves. Bombay, the old name of the city, meaning ‘good bay’, expresses the deep connection between the city and the water.

Unfortunately, extensive development has dramatically reduced these natural features. More than 2,028 hectares of green cover was lost in only five years from 2016 to 2021, according to the Mumbai Climate Action Plan document unveiled two years ago.[7]

Urban parks throughout the city, while contributing to the green space, cover only 3.7 percent of the city’s built-up regions. Mumbai’s open space per capita is starkly low compared to global cities: New York boasts of 2.16 hectares per 1,000 inhabitants and London 1.96 hectares, while Mumbai lags with a mere 0.01 hectares.[8] This scarcity underscores the critical need for more green spaces to enhance water absorption and reduce surface runoff.

The rapid urbanisation and construction boom[9] have led to increased impervious surfaces, where concrete and asphalt replace natural landscapes. This change has significantly reduced the ground’s ability to absorb water, resulting in increased surface runoff and a heightened risk of flooding. Natural drainage channels and water bodies have been filled or encroached upon, diminishing their capacity to manage rainwater effectively. Industrial and domestic waste have polluted rivers and creeks, further hampering their function as natural drainage systems.

To mitigate future flooding and enhance the city’s resilience, Mumbai must convert its remaining blue-green assets into sponge infrastructure, and expand them where possible. This involves restoring wetlands and mangroves to regain their natural absorption capacity, creating urban green spaces to enhance infiltration and reduce runoff, revitalising riverine systems to improve their drainage function, and implementing sustainable urban planning that balances development with the preservation of natural landscapes. Chennai has embraced the sponge city concept.[10]

A path to sustainable urbanism

The vision of transforming Mumbai into a fully functioning sponge city rests on integrating its natural blue-green bodies into a cohesive and interconnected system. By bringing Mumbai’s natural systems to the forefront, we can cultivate an urban approach where ecological principles are embedded into, rather than imposed onto, urban development. Recognising the fundamental intertwining of nature and cities will not only make Mumbai resilient to calamities but also enhance the city’s livability and its residents’ experiences.

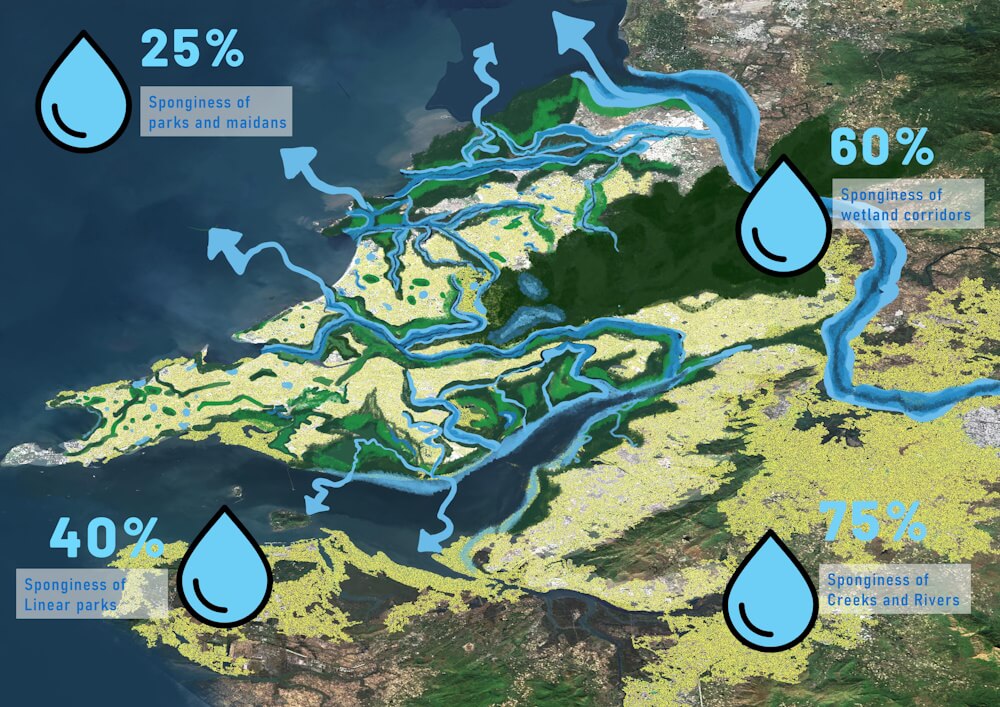

To make Mumbai a sponge city, it is crucial to identify and define the varying degrees of wetness across its landscapes. Each degree represents a specific threshold of sponginess, which can be organised in a scalar approach to ensure comprehensive water management and ecological balance.

First degree of wetness: Neighbourhood parks and maidans

The initial step involves converting Mumbai’s parks and maidans at the neighbourhood level to effectively collect and store rainwater. This approach aims to capture rainwater within each neighbourhood, thereby minimising surface runoff and maximising water absorption. By creating localised rainwater harvesting systems, neighbourhoods can become self-sufficient in managing stormwater, reducing the burden on the city’s drainage infrastructure.

Second degree of wetness: Linear parks and biodiversity activators

The next degree focuses on transforming existing linear ecological stretches into linear parks that connect multiple neighbourhoods. These infrastructures streamline stormwater systems while acting as essential biodiversity activators, enhancing socio-ecological balance. An example of this is the Irla Nullah pilot project in Juhu, initiated seven years ago.[11] This project demonstrates how linear parks can be created to serve dual purposes of stormwater management and biodiversity enhancement.

Third degree of wetness: Revitalising water basins, mangrove corridors, and wetlands

Revitalising Mumbai’s water basins, mangrove corridors, and wetlands involves re-establishing water flow, controlling invasive species, and replanting native vegetation. These efforts are crucial for revitalising wetland ecosystems and safeguarding their ecological functions. Wetlands, especially mangroves, serve as vital buffers between land and sea, protecting coastlines from erosion, controlling floods, providing habitat for diverse fish species, and cleaning coastal waters. Their ecological importance cannot be overstated, as they participate in elemental cycles, aid in contaminant cleanup, stabilise the local microclimate, recharge groundwater levels, and prevent urban flooding.

Fourth degree of wetness: Restoring water networks of creeks and rivers

The final degree involves restoring the natural water networks of creeks and rivers, which have often been relegated to sewage nullahs (drains). Recognising the crucial role these water bodies play in Mumbai’s ecology is essential. The indigenous communities of Mumbai, such as the Kolis, were historically well-versed in managing these water systems and dependent mangroves. However, urbanisation has significantly altered these landscapes. By revitalising rivers like Dahisar, Mithi, Oshiwara, and Poisar, which flow into the Arabian Sea through the Malad, Mahim, Marve, and Thane creeks, we can restore these vital habitats and create a vibrant environment for aquatic flora and fauna. This revitalisation can also revive traditional communities that once thrived on these water channels.[12]

Through this step-by-step scalar approach, Mumbai can transform into a fully functioning sponge city, balancing urban development with natural resilience. This paradigm shift towards sustainable urbanism not only ensures a calamity-proof city but also fosters a deeper connection between its inhabitants and their environment, paving the way for a harmonious coexistence with nature.

Way forward: Integrating nature into urban resilience

The way forward for flood-prone cities like Mumbai lies in bringing natural systems to the foreground and embracing an approach where ecological principles are woven into, not merely added onto, urbanism. By recognising the fundamental intertwinement of nature and cities, we can direct our development in more naturalistic ways. This reorientation will reinstate the longstanding relationship between the land and its people, creating a resilient and enriching urban experience that stands the test of time. By fostering parochial collective spaces that blend the public and private realms, we redefine our connection to place, ensuring cities that are both calamity-proof and vibrant for generations to come.

Transforming Mumbai into a sponge city is not just a vision but an urgent necessity. The potential benefits of enhanced urban livability, ecological health, and resilience against climate change are immense. By adopting and implementing the sponge city concept, Mumbai can lead the way for other flood-prone cities, setting a precedent for sustainable urban development that harmonises with nature. This proactive approach will safeguard future generations and create a vibrant, resilient urban environment that honours its natural heritage while embracing innovation and sustainability.

Shreya Rangaraj is an architect with a specialised background in urban planning, having contributed her expertise at a multidisciplinary urban strategy practice. Her professional focus lies in the exploration of ecology’s impact and its integration with various societal layers, emphasising climate adaptation strategies and the creation of equitable urban environments. She is an incoming candidate in the Regional Planning program at Cornell University, aiming to further integrate sustainable and equitable practices in urban development.