The significance of the Supreme Court judgment unequivocally and firmly stating that Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution now encompass “the right against the adverse effects of climate change” is far-reaching, indeed. This is India’s first-ever judgment clearly recognising – and bringing on record – the perils of climate change as well as linking its impact to human rights.

The unambiguous words came last month – and were uploaded[1] early April – in a case that did not have directly to do with climate change but argued the impact of high-tension power lines on the Great Indian Bustard species.[2] Led by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, the bench comprising Justices JB Pardiwala and Manoj Misra, expanded the scope of the two crucial Articles and firmly placed climate change impacts within the ambit of human rights, especially the Right to Life.

Connecting it to the right to a clean environment, the bench noted, “Without a clean environment which is stable and unimpacted by the vagaries of climate change, the Right to Life is not fully realised. The right to health (which is a part of the Right to Life under Article 21) is impacted due to factors such as air pollution, shifts in vector-borne diseases, rising temperatures, droughts, shortages in food supplies due to crop failure, storms, and flooding. The inability of underserved communities to adapt to climate change or cope with its effects violates the right to life (Article 21) as well as the right to equality (Article 14).”

This is a landmark judgment for at least two reasons. It expands the scope of Article 21 and Article 14 which determine quality of life for all Indians, and it powerfully interprets human rights to include the adverse impacts of climate change. The words from India’s apex court have come not a day too soon as climate impact is felt all around, from large and congested metropolitan cities to far-flung villages.

Illustration: Maitreyee Rele

Why the judgment matters to millions

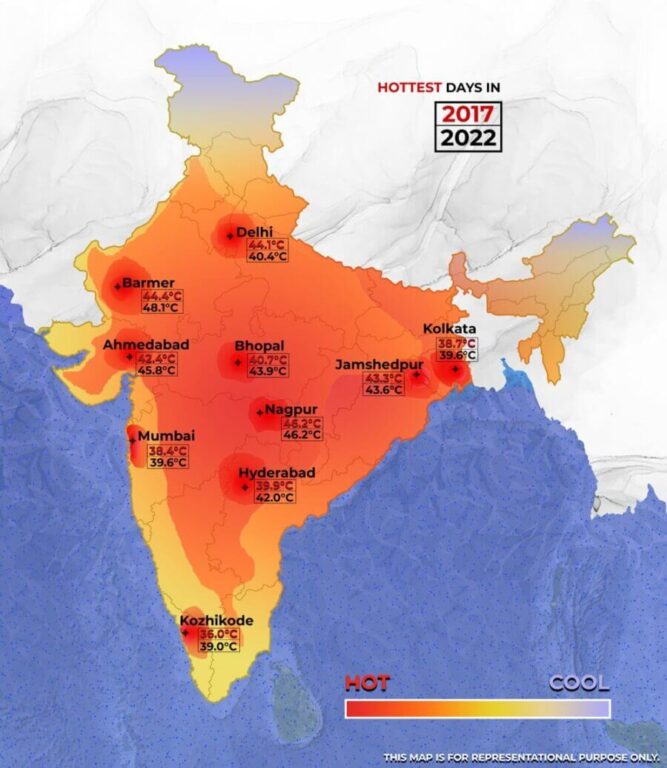

The scale and scope of adverse impacts of climate change are humungous in India, unseen in other parts of the world. Most of India suffers high levels of heat stress[3] and drought every summer. Parts of the country see hailstorms and unseasonal rain which destroy the standing crops besides taking lives.[4] The monsoon patterns have altered, bringing more rain in a shorter time.[5] This year brought a snowless winter in Kashmir[6] and projections are for unbearably high summer temperatures across the country. The measurable impact on people is alarming; the unrecorded impact on both nature and people is unimaginable.

Researchers found that between 2000-2004 and 2017-2021, India saw a 55 percent increase in deaths due to extreme heat, according to Lancet countdown report 2022.[7] Studies have shown that nearly 310 million Indians live in low-elevation coastal areas while another 360 million people are poor without the means to face climate impact, and 1.77 million are homeless and literally at the mercy of elements, according to Government of India data.

Nearly 80 percent of the country’s population lives in districts that are highly vulnerable to extreme weather events, states this study.[8] With millions living in “climate hotspots,” where changes in climate negatively affect lives, livelihoods and living standards, and the number of such hotspots rising as climate change worsens, it is projected that by 2050, at least 148.3 million Indians will be in severe hotspots.[9]

The magnitude of the adverse impact of climate events has been documented in studies and reports for years now. The SC judgment focuses urgent attention on them. It pushes the Government of India as well as state and city governments to make climate impacts a priority in their policies, programmes and schemes. It offers the people of India the best opportunity to push governments, at all levels, to increase and broaden climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Illustration: Maitreyee Rele

The onus on governments

Going forward, governments will have to evolve and implement clear climate action plans, and prioritise sustainable development and environmental conservation. This means recognising and restoring the green and blue ecological networks in cities, and giving primacy to building with nature.[10] It follows then that development and infrastructure projects will have to be specifically evaluated for their climate impact – and the likely adverse effect on people.

The judgment foregrounds natural areas, especially in cities, and the urgent need to conserve them given the critical role in combating climate impacts. Trees and forest cover, open spaces as holding areas, green zones, permeable surfaces to allow water to percolate, sea fronts and creeks, rivers and lakes, wells and other water bodies are climate warriors and buffers. Protecting and inter-linking them provides cities with the best possible chance against climate impacts. Natural areas can no longer hold mere potential economic value.

The primacy to natural areas implies that the prevailing approach to urban planning will have to change too – from the present land-use plan devoid of ecological context to nature-based planning[11] in which ecology provides the context for development. This should ideally lead to a review and revision of land-use plans, building bye laws and codes, and the buildable area and materials allowed; design and construction norms will have to change too.

With natural areas in neighbourhoods becoming important, people can collectively work – with or without authorities – to map and record them as the first step towards their statutory protection. Lastly, state and city governments will have to draw up climate action plans, which will have to be statutory plans rather than a wish list, as the Mumbai Climate Action Plan[12] was. Several states and cities have such plans but without a binding framework. In the context of human rights, these plans will become more significant though it is important to note here that people, especially the poor and vulnerable, have been combating climate impacts despite or in the absence of such plans.

The judgment is significant also because it poses a structural question. Should states and cities now have one authority or department at all levels of the government that deals exclusively with climate change, and should the scope and powers of those that have such departments be considerably widened as climate change worsens? For example, some cities with climate action plans have independent heat action plans, or tree authorities often function in their silos, or state government departments that deal with agriculture and transport hardly work in tandem with climate change departments where they exist.

Illustration: Maitreyee Rele

Bringing legal clarity and perspective

It is not that the Constitution did not provide such protection or previous judgments and orders of various courts across India, including the SC, have not focussed on climate change. However, the significance of this judgment is that its articulation goes well beyond others. In its words: “Despite a plethora of decisions on the right to a clean environment, some decisions which recognise climate change as a serious threat, and national policies which seek to combat climate change, it is yet to be articulated that the people have a right against the adverse effects of climate change…As the havoc caused by climate change increases year by year, it becomes necessary to articulate this as a distinct right. It is recognised by Articles 14 and 21.”

The Constitution has references in Article 48A (the State shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country) and Clause (g) of Article 51A (it shall be the duty of every citizen of India to protect and improve the natural environment). These now become part of the rights. “These Articles are important sources of the right to a clean environment and the right against the adverse effects of climate change,” the judgment stated.

Similarly, on the interpretation of climate impact in the context of human rights, the bench was categorical. “Of late, the intersection between climate and human rights has been put in sharp focus, underscoring the imperative for states to address climate impacts through the lens of rights…States owe a duty of care to citizens to prevent harm and ensure overall well-being. The right to a healthy and clean environment is undoubtedly a part of this duty of care. States are compelled to take effective measures to mitigate climate change and ensure that all individuals have the necessary capacity to adapt to the climate crisis,” the judges noted, pointing out that the interconnection included the right to health, indigenous rights, gender equality and right to development.

While articulating this, the judgment drew attention to the international recognition of climate change as a human rights issue. The 2015 UN Environment Programme report outlined five human rights obligations related to climate change, the UN Special Rapporteur emphasised in 2018 that human rights necessitate states to establish effective laws and policies to reduce greenhouse gas emission, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued an advisory in 2017 affirming the right to a healthy environment as a fundamental human right, the judgment pointed out. While emphasising the role of clean energy, it stated, the right to a healthy environment encapsulates the principle that every individual is entitled “to live in an environment that is clean, safe and conducive to their well-being”.

Earlier this month, in Strasbourg in France, another court demonstrated how climate change as human rights can play out. The European Court of Human Rights held that the Swiss government[13] had violated human rights of its citizens by not meeting its targets on climate and not doing enough to stop climate change. The Swiss government, of course, argued that the human rights law does not apply to climate change. The court held otherwise and ordered it to pay Euros 80,000 ($87,000) to the group that brought the case to the judiciary.

We, in India, may be years away from holding governments legally culpable for not meeting climate targets but this SC judgment has clearly put us on that path, where climate change and fundamental human rights merge.

Given the sharp focus of Question of Cities on climate change, we present a selection of essays and ground reports published on this theme since 2022.

Cover illustration: Team QoC