In south-eastern Bengaluru, three lakes saw restoration efforts in the last few years. Kaikondrahalli, Kasavanahalli and Sowle Kere, among the city’s many degraded and ruined lakes, were nursed back to ecological health by groups which included migrants to the city. The process of restoration and conservation of the lakes as “places” helped to not only demonstrate environmental placemaking but also fostered people’s stewardship.

Analysing the process for an academic study, Amrita Sen and Harini Nagendra, professors of Sustainability, remarked in their paper: “…how environmental placemaking (led) to a fundamental transformation in human-nature conservation relationships…how experiences of environmental placemaking are constituted by migrants into cities and are fundamental in making the city and local ecosystem a place of cohabitation, fostered by growing emotional attachment which stimulates a desire for environmental action.” [1]

Coasting along the shoreline in Mumbai’s upscale neighbourhood of Bandra was a stretch of land turned into a dumping ground and den for anti-social activities. After the authorities planned to turn a grounded ship into a floating hotel there in the 1990s, people protested and claimed the area. Under the aegis of citizen groups such as Mumbai Nagrik Vikas Manch and Bandra Residents Welfare Association, led by the late journalist-environmentalist Darryl D’monte and architect-activist PK Das* who steered a movement to reclaim and renew Mumbai waterfronts, the 1.2-kilometre stretch was converted into a promenade.

Constructed with the funds of the then Member of Parliament and actor Shabana Azmi, the promenade became one of the highlights of Mumbai. Scores of people walked and jogged there every day, couples carved out their spaces, benches allowed people to take in the sea and sunsets, an amphitheatre became the site of cultural programmes and protests – the placemaking nurtured a relationship between people and the sea. The biodiversity in that stretch showed variety too.[2] After 20 years, two years ago, the Association informed the authorities that it would not be able to maintain the promenade.

In Kathmandu, Nepal, the historical artificial pond Rani Pokhari was restored to its old glory two years ago with public participation, natural resources, and indigenous knowledge. In Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu in India, the busy and congested Cross Cut Road was redesigned with bright markers, street signage and furniture to keep vehicles restricted to the centre lanes and open the street for cyclists, pedestrians, little hangout spaces opposite shopfronts, and so on; the pilot lasted only two weeks. In the United States’ Philadelphia, The Porch at 30th St. Station, an undesirable place, was turned around into a vibrant square with café tables, food trucks and pop-up musical performances.

These are but a few of the tens of examples from around the world that demonstrate what placemaking can do. From streets to entire cityscapes, placemaking has reimagined inert or uninteresting places, reinvigorated them with new energy and opened them up to people in the neighbourhood and, where possible, reenergised the relationship of the place with its ecology. Placemaking is the buzzword in city-making and urban planning – and needs a closer critical look.

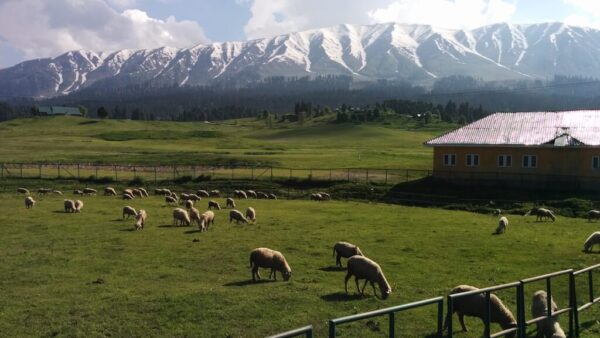

Photo: Ashwin Kumar/ Creative Commons

Placemaking is more than places

Placemaking is described as creating places in cities through design but this can be a limiting way to understand the concept. At its core, placemaking is not merely about creating places through design but transforming public places with community engagement to create better connections between people and the places they inhabit.

It is not only an outcome but a process in which people collaborate with one another as well as with the relevant authorities to transform a place beyond its material dimensions in order to create better access, more connections and comfort for the entire neighbourhood. Placemaking efforts that are sustained with public funds or crowdfunding are most representative. Done with the larger perspective and purpose, placemaking has the ability to allow us to re-envision the city and reconnect people with nature.

“Placemaking inspires people to collectively reimagine and reinvent public spaces as the heart of every community. Strengthening the connection between people and the places they share, placemaking refers to a collaborative process by which we can shape our public realm in order to maximise shared value,” explains the primer from the internationally-renowned Project for Public Places. “More than just promoting better urban design, placemaking facilitates creative patterns of use, paying particular attention to the physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place and support its ongoing evolution,” it adds.[3]

As private enclaves expand their footprint in cities, their design is meant to keep “other people” out. Some of these spaces may become popular or provide novelty to the city, but they hardly qualify as public places which help foster a sense of community. Placemaking, on the contrary, is usually centred on public places – or should be. It changes an existing typology, and improves its quality and functionality, so that the lives of people around it are qualitatively better.

Ethan Kent, executive director and co-founder of PlacemakingX, said at the Placemaking India Week 2022 held in Udupi recently, that it is “about convergence of causes for places…Placemaking enables peoples’ agency to shape their public realm and in turn for that public realm to shape communities”. A note of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s School of Architecture and Planning explains placemaking as an effort “to build or improve public space, spark public discourse, create beauty and delight, engender civic pride, connect neighbourhoods, support community health and safety, grow social justice, catalyse economic development, promote environmental sustainability, and of course nurture an authentic sense of place”.

Placemaking, as a term, came to be used in the 1990s but the concept in its earliest form and without this nomenclature can be found in the work of urbanists like Jane Jacobs and others who wanted to create neighbourhoods with welcoming public places which met the needs of people living there. In its present discourse, placemaking can sometime be micro projects that are led by designers and planners alone, but this masks the potential of placemaking to create neighbourhoods that are ecologically-sustainable and people-friendly.

Photo: Rajesh Dhungana/ Creative Commons

People at the heart of placemaking

Placemaking which focuses on only creating a place imagined in government or private offices hardly does justice to the movement that it was meant to be; placemaking must have people who collectively transform places in ways that are meaningful to them. The process strengthens a community, deepens the bond between people and their places, and becomes a gradual bottom-up collaborative process to shape their public realm.

The Precollinear Park in Turin, Italy, opened during the COVID-19 pandemic is a case in point.[4] An abandoned tramline was transformed into an outdoor recreational area for COVID-appropriate leisure activities “with wooden seats, bright yellow pallet benches, and flower pots, along a zig-zag pathway that leads towards a small platform that has been set up for events,” according to the Archdaily journal, with the participation of nearly 700 residents of Turin who shared ideas and raised money through crowdfunding.

In the Bengaluru lakes restoration or Mumbai’s Carter Road waterfront too, people’s participation made all the difference – not token participation but a serious collaborative process they took stewardship. People from the area, who live and use the place, are best placed to take the initiative or participate meaningfully in an external initiative to transform the place. But this has to include people from all economic strata to make sure that people with wealth and voice do not monopolise the process.

Fred Kent, considered among the pioneers of the modern placemaking, explained it as “creating communities that have a greater capacity to self-organise – to pilot their own destinies; to express outrage, solidarity or celebration; to exchange and innovate and incubate new ideas, and yes, to bathe in the fountain”.[5] The fountain is the tangible typology and outcome of placemaking; the purpose is greater than that.

Photo: Torino Stratosferica

The purpose is best explained in the four necessary elements for placemaking listed by the Project for Public Places: Sociability, access and linkages, uses and activities, and comfort and image. Each is further explained by attributes. Sociability includes diversity, neighbourly, stewardship, interactive, friendly and welcoming. Access and linkage are interpreted as proximity, connected, walkable, convenient, accessible. Uses and activities include attributes such as fun, vital, useful, celebration, and sustainability. Comfort and image are understood as safe, clean, green, walkable, charming, attractive, and historic.

A less-discussed aspect of placemaking is its ability to create or use art to foster the idea of public place, and also use art as a tool or means of placemaking. In Mumbai’s low-income suburb of Govandi, Community Design Agency (CDA) and a youth group called Youth Sangathan turned a corner of their resettled neighbourhood of Natwar Parekh Nagar into a vibrant art space and safe place. “Haq se, Govandi” (By right, Govandi) was their first art-based intervention in early 2021 with a large wall mural, lights, benches and so on; the mural came from local workshops.

The vibrancy made the place safer for women and girls, and families began frequenting it too. The place is maintained by the colony residents. Natasha Sharma, Lead, Public Arts and Design at CDA, explains, “We chose a corner that was considered unsafe, misused by alcoholics and drug addicts, and a spot for physical fights. We asked the youth what they wanted the space to represent. They said they wanted it to define their identity beyond the common perception of Govandi as a hub of anti-socials. It was the first time that people got together, not for religious or political reasons, but to paint a wall.” Parveen Sheikh, a resident and community representative, is proud of the space. “The mural brought a wall to life…After it was lit up, we understood the impact of the ownership of our community spaces,” she added. Enthused, the group started a library called Kitab Mahal.

Make place with nature

Typically, placemaking has been approached as a design or typology enterprise and divided into four types: Standard, strategic, creative, and tactical placemaking. Some of these approaches do place a value on ecology and placemaking has been embraced by communities as a way to address the Climate Change challenges. However, the ecological aspect is often incidental.

Lately, the concept ‘green placemaking’ or environmental placemaking, which focuses on the ecological aspects of transforming an area, has received some attention. “The ‘environmental placemaking’ would describe the ways in which distinct and disparate practices, meanings and ideologies are utilised towards forging a collective identity for a place of nature, as a shared social-ecological place,” explain Sen and Nagendra who studied the Bengaluru lakes’ placemaking.[6] In fact, Ethan Kent described placemaking as the new environmentalism to co-create far-reaching change for a greener planet.[7]

Not only is there scope but an urgent need to refocus placemaking itself to integrate nature into its vision. It would be most purposeful and successful when it leads to transformation of a site so that the created place is integrated with nature and local ecology besides being accessible and inclusive to people. “…Although the connection with nature is evidently strongly related to well-being, the traditional conceptualisation of placemaking ignores non-human elements and ecological systems as equal parts, or users of space. Consequently, placemaking practice needs to recognise the value of ecological systems in their own right and embrace the interconnectedness between these dimensions,” pointed out Fincher, Pardy and Shaw in their paper.[8]

Placemaking, now and then, has sought to integrate nature. The small town of La Riche in central France “planted over 600 trees and shrubs to lower temperatures in dense areas” through an online engagement platform for its residents to choose locations.[9] Mumbai’s Carter Road project created a place for people as well as integrated it with the natural ecology of the coast. “It has been observed that the present promenade is more sustainable than it was few decades ago. The planning, design, and management of the waterfront has been completely public driven…The design elements (have) enhanced the functionality of the space,” observed a study done in 2017.[10]

“Planning of cities must evolve with the ecological challenges of the time, and this includes placemaking. People and development need to interact with the natural environment,” pointed out PK Das* who led the design-planning of the promenade in consultation with people of the area, “We have a complex set of challenges ahead, for which we need to critically judge old spaces and denounce some methods that have clearly not worked.”

Photo: Kate Joyce/ Creative Commons

The Chicago Riverwalk used the derelict infrastructure along its 2.4 kilometres to create places for myriad activities that people could engage in Using a century-old plan to create spaces for people, boat services, water taxi stops, war veterans memorial and other activities, the park “returned Chicago to its rivers moulding perceptions and relationships…the river has become the city’s living room.”[11]

It is time to move beyond the conservative approach to placemaking, whether micro-level or large-scale, to integrate environmental aspects into the process.

Placemaking as democracy in action

People’s role in placemaking makes it, or should make it, an intrinsically democratic one in which people connect with each other and collaborate on ideas to transform places. Placemaking, done right, ought to be a consultative process with various sections of the society interacting as stakeholders – local governments, people’s elected representatives, non-governmental organisations, community organisations, and private individuals. By asking questions such as “what should this place be turned into, for whom?” the democratic process can get rolling.

However, placemaking as it unfolds on the ground often makes little allowance for the democratic process. In a number of placemaking examples one of the two is observed: A top-down approach with a tiny group of people negotiating with authorities and tweaking the place to suit their needs, or a plan by private agencies and/or corporate interests to the local authorities becomes the default design for the place with people’s assent sometimes sought.

It is only when the placemaking process moves ground-up that it has the chance to become democratic to represent all shades of opinions. Places must bring diverse people together for greater interaction and shared activities; not isolate sections of the community by access. If inclusive public places are the lifeblood of democracy, then they must also be created in that manner to fulfil that purpose.

From this perspective, the role of placemaking is far greater than merely transforming a physical space; it carries the possibility of deepening democracy itself. Placemaking has the potential to be a political movement for equitable public places in which people organise and struggle for their right to the city, across the usual barriers and exclusions, and networking with other rights’ movements such as movement for housing and so on.

Without the larger democratic or community-building purpose, placemaking can easily be reduced to a beautification drive; it is way more than that.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

*PK Das, an architect-activist and keynote speaker at the Placemaking India Week, is the founder of Question of Cities.

Cover photo: Community Design Agency