The technological and industrial advance of the 19th century, of which the city was an important expression, was viewed by many as a symbol of progress, the highest point in human development. The sensitive minds of the time, however, were appalled and alarmed by the haphazard urbanisation, the meaningless growth of cities, their character destroyed and steamrolled into fixed patterns at best, or their degeneration into chaos at worst. Shelley expressed the sentiment when he wrote “HELL is a city much like London”. But Patrick Geddes likened the city “neither to Inferno nor to Paradise but to Purgatory, for before us is the renewal of a great social hope; behind us the disappointment and the suffering of innumerable falls”.

In his Cities in Evolution, he bemoaned the fact that the capitalist greed and relentless industrial growth were playing havoc. Geddes wrote “…Our ports, which have grown up anyhow, our towns, in which factory and railway, slum and suburb, are separated by mere accidents of personal ownership, or crushed together by mere planless growth, and which we then patch and cobble as best we may, at infinite cost and labour, and with no organic unity, no adequate utility, and no beauty when done”.

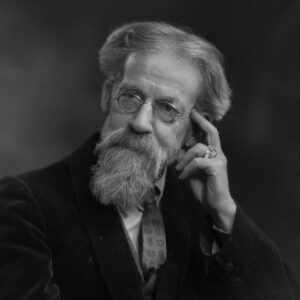

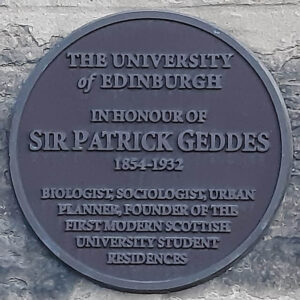

Drawing from the multiple disciplines of biology, botany, history, geography, ecology, anthropology, sociology and civics, architecture, the arts, and gardening Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), a Scotsman, developed a different perspective and a vision of how cities could be improved if principles of town planning were applied. He was confident that his ecological-social approach to civic reconstruction would create an urban environment where nature and people could both flourish.

Ecological cities

Geddes’ idea of a city incorporated, besides considerations of housing, sanitation, and adequate infrastructural facilities, open green spaces, parks, gardens, trees, and water bodies. For the health and beauty of a city, building with and in cooperation with nature was crucial. Geddes believed that the prevalent approaches essentially arose from two disparate philosophies, one that was based on a mechanical division of labour and the other on a unified view of life. Needless to say, Geddes believed in the latter.

His love of nature, imbibed from his family’s close contact with the countryside in his growing-up years, remained with him all his life. It figured in his town plans as an essential part of the urban environment which had to be built with respect to the natural environment because they were so completely intertwined. Not merely in the form such as an isolated garden, a fountain, or a flower bed to beautify a city, but as an important part and presence in the built environment. Simply put, to build with nature, and to treat nature as an integral part of the physical contour of cityscape.

Geddes believed that for human beings, close contact with nature was necessary and beneficial, for it had the power to heal, and to nurture; its presence ensured mental and physical health and happiness to all, life itself. Detailed notes were prepared on every well, ‘nullah’, river, pond, lake, garden, wooded area, wild open space, its existing condition as well as the possibility of its development into a healthy and pleasing public space as well as utility, for the cities he visited, namely, Jubbulpore (Jabalpur), Indore, Patiala, Kapurthala, Balarampur, Dacca (Dhaka), Lahore, Visakhapatnam, Lucknow, Surat, Broach (Bharuch), Bombay (Mumbai), Baroda and many others. They are a testimony to his commitment to planning with nature. In his Indian town planning reports, believed to be approximately 50, Geddes’ larger purpose and principle of city design and development is at full play.

His basic approach to creating humane, healthy, culturally and environmentally rich and friendly cities for all, men and women, rich and poor, old and young without drastically destroying the existing houses, streets, mohallas, open spaces, nature and cultural traditions, and without incurring too much expenditure, is spelt out. In a few reports he praises the municipal and other authorities for their efforts towards improvements, but by and large he sharply criticises their mechanical, wasteful and expensive schemes of city improvement, for neglecting what is valuable and can be restored with less cost and effort.

Photo: Creative Commons

Principles of planning: the larger purpose

Geddes has been considered by some as the father of city planning in modern times. He believed that town planning was not mere ‘place’ planning, it was essentially ‘people’ planning. For Lewis Mumford, his disciple, this was an important lesson. Mumford acknowledged that as town planners they were accustomed to deal with place, but Geddes showed there was no point in planning place except for the benefit of people who had to earn their livelihood by work, and who had other needs such as worship, education, recreation which had to be accommodated and provided for. George Pepler, in The Town Planning Review remarked: “…the blessing was that Geddes was at hand to illuminate us, at the moment when town planning was about to be made, for the first time in our country, a function of government”.

Town planning was not a new special branch of engineering, or of sanitation, building, architecture, gardening or any other fine arts, as most people mistakenly believed. It was not even a new specialisation to be added to the existing ones; its larger purpose, Geddes asserted, was to combine all of them ‘towards civic well-being’. To town planning, he brought the methods of ‘diagnostic survey’ and ‘conservative surgery’, concepts taken from the medical science, which formed the basis for the entire exercise of planning. The former implied an extensive, preferably walking tour of city, meeting and talking to people in order to acquaint oneself with how the city had grown and what problems it faced at present. Geddes’ ‘diagnosis before treatment’ may seem too obvious to warrant attention today, but the idea was new in town planning at that time, and remains neglected even in present times. Conservative surgery essentially meant improvement of the city with the minimum of human and financial cost. He believed that every city had its rundown areas with dilapidated houses, ugly and unhealthy quarters, congested and narrow lanes, natural systems that had fallen into disuse, but which could be upgraded and renewed without adopting drastic and expensive measures of removing or destroying them. He viewed the city as an organism – not as a machine, parts of which could be easily discarded, and it was this belief which underlay his town plans.

In Indian as also in European cities, he had witnessed large-scale destruction of old and insanitary quarters, neglected homes and monuments, and expansion of new streets and thoroughfares, alongside large-scale constructions which were out of sync with the general character and the essential needs of the city. The human and social cost was enormous, most often it resulted not only in high expenditure but also in great human suffering; it also meant loss of history and valuable traditions, and neglect and destruction of valuable natural resources. Much of the work he found was in the hands of civic officials and engineers who were not trained for it, who were unaware of the sociological and ecological aspects of the problems and whose views were largely based on European traditions.

In contrast, Geddes made every effort to provide the best possible living conditions and facilities for every section, including the most underprivileged, at the same time preserve the cultural and natural asset of a city. In Lahore, for example, he was astonished to find that the layout plan proposed by the municipal officials for a particular site, swept away not only the old buildings but also temples, mosques, dharmshalas, and tombs. All the dwellings, shops, and existing roads and lanes were to be destroyed.

In Broach, where similar plans for arbitrary widening of streets were made in committee rooms and offices, he had to remind the administrators and experts that ‘roads and streets are for houses, not houses for roads’. In Gujarat, he pleaded for the broken-down wells to be repaired and maintained; the beautiful local architecture and crafts to be protected and promoted; in southern cities, he recommended the water bodies surrounding the majestic temples to be cleaned and made accessible. In Patiala, he proposed a photographic exhibition of the old dilapidated houses so as to evoke a sense of pride among the inhabitants. In Dacca, he suggested measures to protect the ‘Khals’, a natural drainage system of great efficiency and beauty, from further deterioration.

He vociferously argued again the prevalent practice of concretisation of water bodies to control the mosquito menace. In every city, he identified open spaces, large and small, which could be planted with suitable trees, or turned into parks, even small vegetable gardens. Everywhere he tried to convince officials and influential local citizens to establish small museums to educate the citizenry in history of their cities, the good, bad and ugly and to reveal the potential for their improvement.

Role of the planner

This is where the town planner could intervene, to discern the pattern of growth, to understand the potential, to recognise the possibilities within, to educate the inhabitant of the city. And having shown them the ideal – help them work towards it, in thought and in action. This is what Geddes meant by evolutionary progress, a non-mechanical process, but ever changing and ever challenging. So, for him, as Wendy Lesser points out, the planner is responsible for translating the city’s character and aspirations into a form that ordinary people can understand and identify with it. He is required to use his judgment, and at the same time to grasp the reality as it exists. For this, local knowledge and understanding, along with consideration and tact was required to deal with the needs and wishes of people. What was also required, alongside technical expertise, was “moral influence and energy” and “civic enthusiasm,” to use Jaqueline Tyrwhitt’s words from Patrick Geddes in India, to awaken the people to their own needs and responsibilities.

Geddes was different from other city planners, his predecessors as well successors, in another sense. He did not want to design a city in accordance with a pattern, there was no one pattern, one design, and he did not have one which could be used to make a city. Cities were not made from nothing; they grew and had life of their own. Geddes used the beautiful metaphor of the city as “complicated tapestry, eternally in the process of being woven,” as Lesser points out. A lesson for us to learn is that too many factors, human and non-human, go into weaving this tapestry.

Because each city is unique, different in its own way, has a soul and a spirit which characterises it, therefore, it must also be planned, individually, with due respect for its individuality. In refusing to create an urban ideal, he opposed “those town planners who design a shell and then pack their snail of a would-be progressive city into it, not discerning that the only real and well-fitting shell is that which the creature at its growing periods throws out for its own life,” as Lesser described. Tragically, we are witness to modern cities which are made, more and more, to resemble one another, like clones of an imagined ideal city, complete with the symbols of modernity but bereft of a soul and a spirit.

For Geddes, the ideal was to have a general ‘synoptic’ view of the larger whole and at the same time a closer view of the smallest detail on the ground; both were important, they provided meaning and substance to one another. That is why he insisted on detailed surveys, minor and major alterations, interventions, but only to come closer to the ‘ideal’, the force that guides all creative energy not to a Utopia but ‘Eutopia’, not a dream but a goal. Town planning required town planner, gardener and architect to come together to provide a unified scheme, to look at the existing condition, the way the place had grown, recognise its adversaries, difficulties and defects, and adopt measures to correct them.

Photo: Kim Traynor/Creative Commons

The Geddesian model was criticised for placing too much responsibility on the planner, it demanded that she/he understand and educate others about the relationship between humans and their environment; to identify the needs of people and place, to propose action and make it understood by large numbers of people and make them partners in the action. It often required commitment and ability to change attitudes, and behaviour; to educate, convince and motivate. Thus, for him, the planner had no less a role than as agent for social and human evolution.

Indeed, it was a tall order, but the business of developing urban environment, both built and natural, was a serious business which could be undertaken only by people of exceptional capabilities and education of high order. Geddes demanded it of himself and stretched his abilities to the utmost in his role as a town planner. But then he was not just a town planner, he was a lot more. He used every skill and means at his command in the form of maps, survey reports, photographs, exhibitions, pageants, workshops, and of course writing (pamphlets, articles, books) to propagate the idea of civic renewal. The university, institutions of learning, and professionals had an important role in strengthening the sense of citizenship among ordinary people. For Geddes, the concept of citizenship was of utmost importance, and sociology and civics carried the responsibility to identify the positive tendencies and enthuse citizens to actualise them.

It is in the context of the contemporary urban problems in India, and all over the world, fast reaching crisis proportions in both social and environmental spheres that the Geddesian approach to urban planning and development acquires tremendous significance. It is worth revisiting values and practices of urban planning, no longer fashionable, that may offer a more ecological and humane perspective, if cities are to be saved from becoming ‘Hell’ in Shelley’s words.

Indra Munshi, is retired Professor and Head, Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, which was set up by Sir Patrick Geddes as the first Professor and Head in 1919. She is also the executive editor of the Indian Journal of Secularism (IJS) brought out by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS), Mumbai. Her most recent book, “Patrick Geddes’ Contribution to Sociology and Urban Planning – Vision of a City,” has been published this year.

Cover photo: Byron V/Creative Commons