The first passenger train that started from Bori Bunder to Thana on April 16, 1853, took a halt at Chendani Koliwada (near Thana) where we come from. Although the Kolis have supported development, our forefathers did not realise that the train would take away our water and our trade would shift to the southern part of the new city of Bombay. The British never tried to rule us. In fact, the Kolis had an alliance with them to help them navigate around the islands of the city for business. The seven islands were covered with marsh and mangroves. With the help of our boats, the waterways between the islands were land-filled and the city was built.

Over centuries, as the city developed it became more polluted which, in fact, ruined our sea. We used to fish only within three kilometres of Mumbai’s coast but now fishermen have to go much farther. A variety of fishes used to go into the estuary to lay eggs, but the pollution and encroachments on the city’s rivers have ruined this breeding cycle and broken the pattern. Now the fish go elsewhere.

Though the Colaba Reef still serves as a breeding ground for Bombay Duck, most breeding grounds have moved far away from the city. We know that the city’s development projects as well as sound and light pollution together are destroying the natural breeding grounds and driving the fish away.

Our koliwadas are categorised as slums, they are looked down upon as they emanate the smell of fish which many have an objection to. The city is using our fishing grounds as dumping grounds to keep itself clean while labelling the Kolis as ‘dirty’ because our homes smell of fish. But it is the same fish that they love to eat.

The Kolis want to continue to stay in our villages, the koliwadas. The number of koliwadas may vary – the government says around 30-32 but we think there are many more – but we know how to live in harmony with nature. We may be termed “primitive” by many in the city but we have an equation with nature in this city. The disappearance of fishing and our fishing grounds, and the change in our status from Scheduled Tribes to Special Backward Classes have left us without any land rights.

There are constant attempts to take us away from the coast or bring the city’s development into our koliwadas. By slowing down fishing activities, some believe that koliwadas will cease to exist. History will show that this is far from the truth. The Kolis were here before the city was.

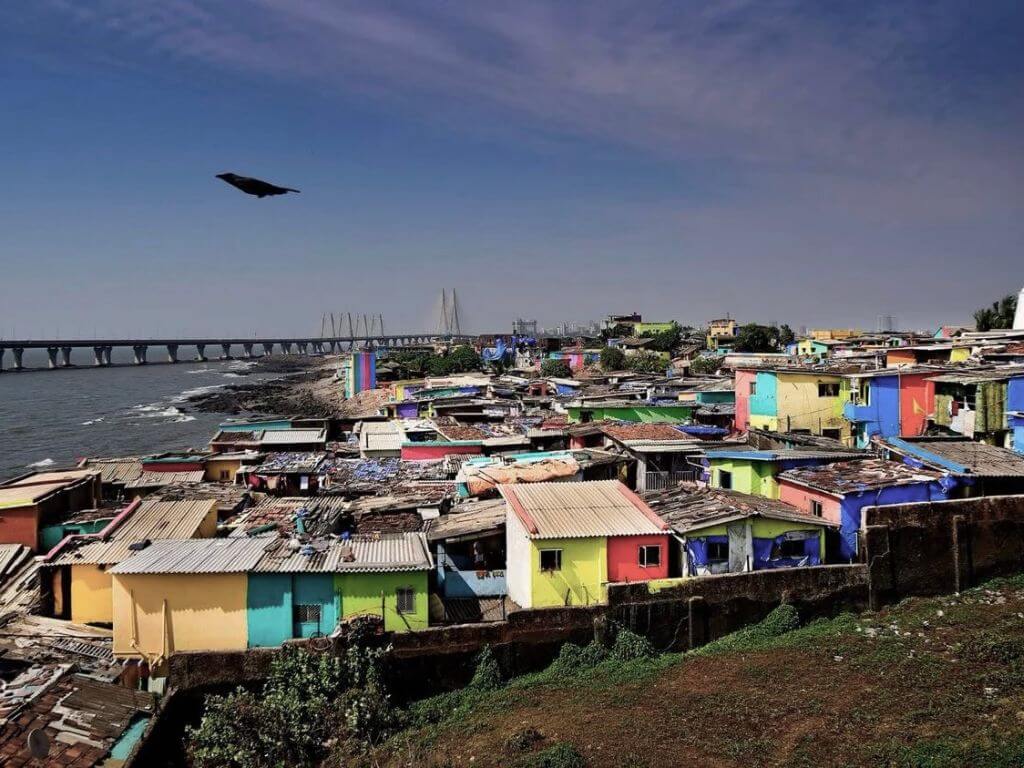

Photo: Madhav Pai/ Flickr

The Kolis and Mumbai’s development

The Kolis have good knowledge of the sea and its behaviour. That’s how our settlements could sustain for ages along the shores. Our work and practices happen on land, in water, and the space in between both, but modern city planning or governance has never used this ancient knowledge. If Mumbai is flooded or encroached by the sea, we have something to say about it but are unheard.

Our voices are heard only when governments want to, usually to fulfill their own motive. Koliwadas have been nurtured only as vote banks. Development projects have affected the environment and the hamlets in which the Kolis live a self-sufficient life. Across koliwadas, we are resisting the continuous encroachment on land and sea through various plans and projects done in the name of development. This, we know, eventually profits only the authorities and developers. The land politics, which is rampant in the sea-facing plots, violates the fundamental rights of the Kolis.

As a community, we have been in favour of development, mingling easily with whoever came to the seven islands, but what is happening now is hurting us. Our hamlets are under the constant threat of being ‘redeveloped’ for the city’s perceived greater gains. We are not slum dwellers, we are the original dwellers in our koliwadas.

We know the seasonal nature of fish, however, the city’s demand for fish does not match the seasons. In the name of development and city planning, the sea corridors, which are rich and abundant with innumerable species of fish and generate high revenue, are destroyed because our voices went unheard. This has resulted in lower catch in the waters around Mumbai. Youngsters do not find fishing and its trade lucrative anymore. The disappearance of marine species has meant that we do not now have parts of our staple diet.

Our history and traditions

The Kolis are known to have started off as traders after settling in the islands of Bombay. While dried Bombay Duck is one of the oldest commodities that was traded with lands as far as the Middle East and Africa, the Kolis also dealt in other items. They started fishing for trade in the islands in the 1850s which grew by leaps and bounds after the Blue Revolution a century later in the mid-1960s. The Kolis survived as traders for ages. As a community, we fish and trade. Chendani Koliwada, where we are from, is not a fishing village but we are still Kolis.

Our family names are after occupations related to trade and ships. So, historically, Nakhawas were boat owners, Tandels were ship captains, and Kolis were helpers on the ship decks. We took these family names, or surnames, because the British needed a way to distinguish us. Until then, our names were followed by the names of our fathers and grandfathers. This has created discrepancies for some and, as a result, some of our land rights are disputed.

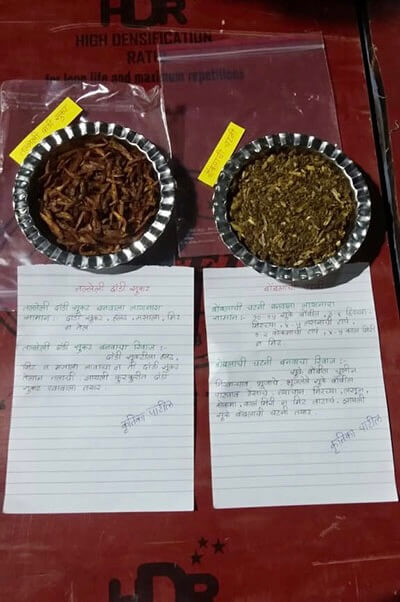

Photo: Tandel Fund of Archives

Living in the space between the land and the sea, the Kolis began to understand the patterns of the ocean and the sky which is where, we believe, our deities come from. It was knowledge passed down that the moon controlled ocean tides and, therefore, fishing was dependent on the moon’s cycle. An example of this is the fleshy crabs found in Koli homes during the new moon because it means low tides which allow marine species to become nutritious. When the full moon causes high tides, the marine species have to struggle to survive and, thus, they lose their fats.

Chandra puja (moon worship) is a practice followed in Koli homes every month. This has now been replaced with Chaturthi. Large fish from the sea, including Bairidevi or the whale shark, were worshipped in the belief that they would protect the community. The mingling of Kolis with newer settlers of the city meant that our religious practices evolved to include new gods which led to the eventual decline in the worship of the community’s deities.

The Marathas and bhakti philosophers were among those who converted the Kolis to Hinduism. Now, some Kolis visit Shirdi too. Among the oldest traditions are the dhavla folk songs sung to explain each ritual of a Koli marriage which find mention in an early 12th century text called Manasollasa. Before Brahminical influences, Koli marriages did not have priests; instead, dhavlarines or women folk singers conducted rituals with their songs.

Erasure of role in city-building

The Kolis have been around in Bombay-Mumbai for generations and have helped develop the city. However, our role in building the city has not been documented as that of other communities who were involved. This lack of documentation has meant erasure. We have become a special (exotic) species.

People come to study the Kolis but many come with their own perceptions. It becomes difficult for them to understand and contextualise how we feel and think given our several layers of history with the city. Some also hesitate to share their findings. We realised then that information and knowledge about our community can play an important role in shaping the city’s future.

The archives and a fund

When koliwadas were declared as slums, it made us angry. Instead of protesting on the streets, as artistes we devised ways to bring our stories into the limelight. This is how the Tandel Fund of Archives started in 2019 to document and share the knowledge about the Kolis and their culture. Our museums and documentation are our medium of protest.

The idea is to have the Kolis share their stories and store them in an accessible place. In our travelling museum, we encourage the community to bring what is important to them in writing or as photographs, and allow us to document it all. The first few days have no exhibits, then people open up with their unique stories, texts, literature and artefacts. We want to decolonise the idea of a museum. The community decides what is museum-worthy and how they want their stories featured.

The fund is also a revival of sorts. When fishermen would be at sea for weeks and months, there was a fund that supported their families especially if they were stuck at sea, or died in other countries, or were exploited by money lenders. This is why we called it the Tandel Fund of Archives.

We have been documenting recorded and unrecorded imagery, sacred practices, food heritage, and ancient linguistic knowledge as oral stories and poetry. We also publish books and are in the process of building an in-house reference library over the next 20 years.

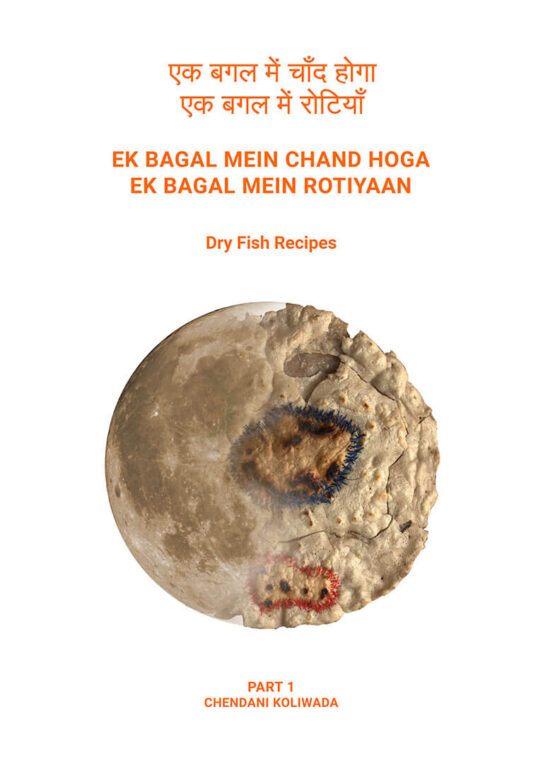

Photo: Tandel Fund of Archives

Saving the linguistic culture

The Koli linguistic culture had not been recorded in or as literature. In the archives, we are doing it as one of the first languages of the early inhabitants of this city. With urbanisation, it has been lost to newer generations. We declared September 1 as the Koli Language Day. The language includes unique names of fish which could help us know the varieties that existed. For example, barnacles are called ‘bocharee’ and oysters are called ‘kalva’. We also eat fish that others do not know, our language has helped us preserve that.

We aim to record the ancient knowledge, these socio-cultural practices which are on the verge of vanishing forever – our oral history that comes from our language, customs, traditions and culinary practices. We are keen to explore if the Koli language can help restore our ocean affected by Climate Change.

The work done for Tandel Fund of Archives has enabled us to celebrate the remembrance and loss of the Bombay Duck, which is an iconic symbol of Mumbai. The occurrence of Bombay Duck around Mumbai’s waters has reduced drastically due to the city’s waste policies. Through the travel exhibition Critical Zones by Goethe, along with artist Stéphane Verlet Bottéro, we are displaying a mummified version of the Bombay Duck to depict this.

The older generation is resigned to the fact that things won’t get better. They just want their homes close to the sea because their food is important to them. However, we want our koliwadas, which have always been a part of the seven islands, to be given heritage status. For this, it is important to organise and bring the community together, and document. If the Art Deco buildings on the sea are heritage, are koliwadas not the real heritage of Mumbai?

Kadambari Koli is a Mumbai-based artist and teacher with MVA. A co-founder of Tandel Fund of Archives, Kadambari has been actively involved in documenting the stories of the fishing community.

Parag Tandel is a Mumbai-based artist and auto-ethnographer. Some of his solo exhibitions include ‘Pregnant Room 1’ (2008) and ‘Pregnant Room 2’ (2010), both showcased at Pundole Art Gallery, Mumbai; ‘Chronicle’ (2016) at TARQ, Mumbai; and ‘Autopolisphilia’ curated by Noopur Desai at Sudarshan art gallery, Pune, India (2018).

Cover photo: Top shot of Worli Koliwada. Courtesy Conde Nast Traveller.