Byrnihat town in Ribhoi district, Meghalaya, has hardly graced news headlines or discussions on air pollution through 2023-24 but it has been the most polluted place in India, even topping the notorious Delhi. Begusarai, in Bihar, topped the list of the most polluted city in the world, according to the World Air Quality Report 2023 released by Switzerland-based IQAir in March this year[1] but it does not ring a bell for anyone when air pollution is mentioned.

Byrnihat and Begusarai, as polluted cities, exemplify the silent crisis that’s sweeping across India on air pollution – in the din of pollution emergency in Delhi and Mumbai, a number of smaller cities and towns have been getting little attention in national conversations and concerns even as the air quality worsens in them, many of them struggle to even acquire monitoring equipment, and only a few have clean air action plans in progress. With millions affected, it is a crisis that needs urgent attention at national and state government levels.

Byrnihat and Begusarai are among the 131 cities and towns under the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) launched in 2019 to reduce particulate matter pollution by 20-30 percent by 2024, using 2017 as the base year. Clearly unattainable, the target has been revised to 40 percent reduction by 2026, using 2019-20 as the base year. These, in government terms, are non-attainment cities or cities that consistently fail to meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for PM10 or N02 over five years. The non-attainment cities collectively have a population of approximately 295 million people – around 21 percent of the country’s population.

This research paper[2] published in Nature states: “Large cities or metropolitan areas draw the most attention in relevant studies, and the small- and mid-sized cities, especially those in developing countries, are heavily under-emphasised. However, virtually all world population growth and most global economic growth are expected to occur in those cities over the next several decades. Thus, an overlooked yet essential task is to account for various levels of cities, ranging from large metropolitan areas to less extensive urban areas, in the analysis.”

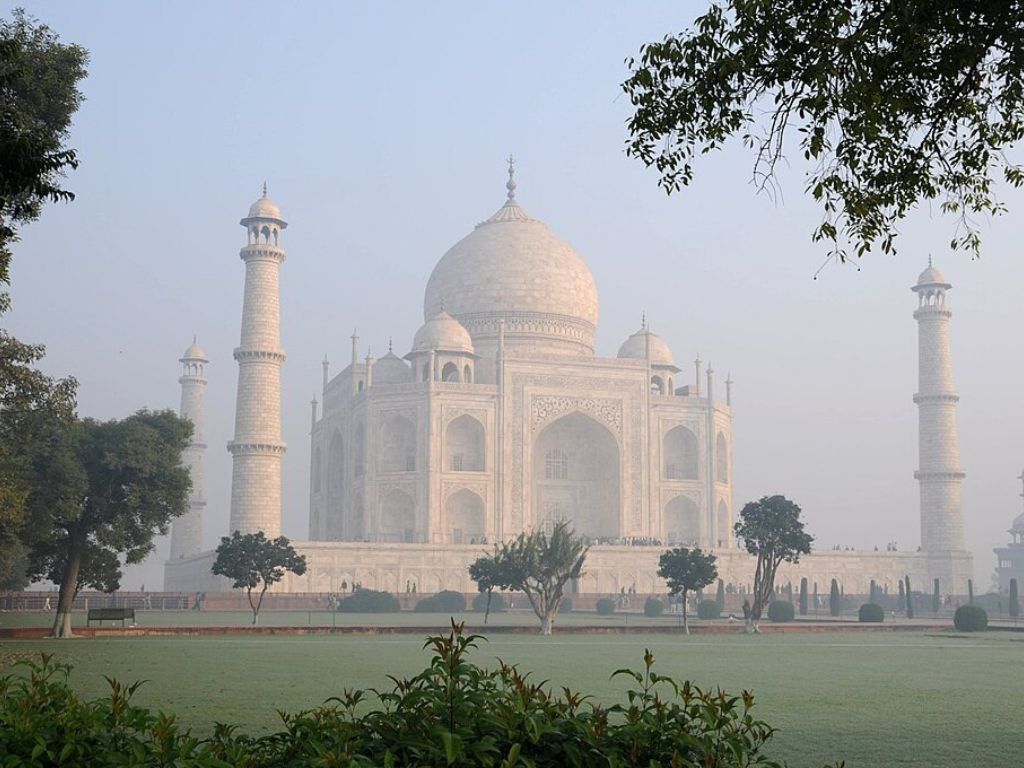

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

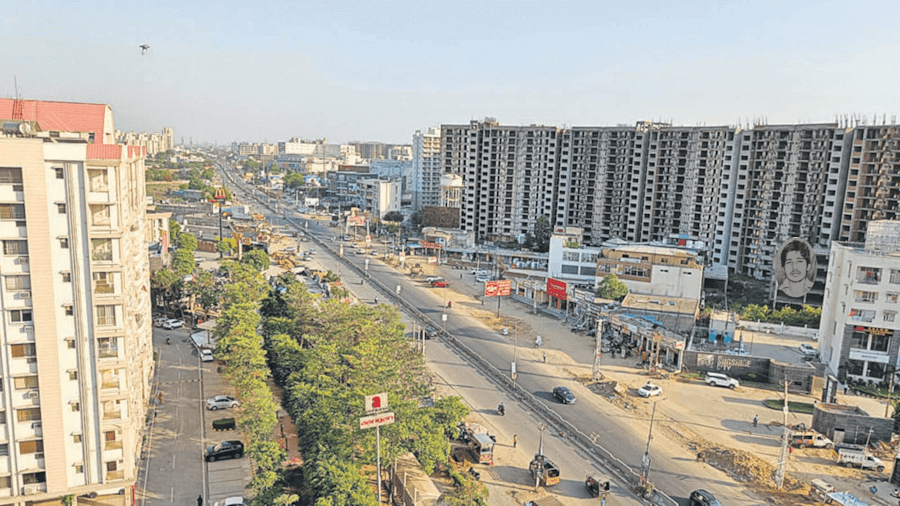

Kolkata-based advocate Upama Bhattacharjee, crusading against air pollution, says that most Tier 2 and 3 cities face poor air quality mainly because of infrastructure construction such as metros, bridges, highways that generate noxious dust and emissions; this also leads to traffic congestion which adds to the emission load. “These coupled with the laxity in the authorities’ approach to apply the laws means Tier 2 cities are often neglected as the bigger cities are in the limelight due to extraordinary levels of air pollution,” she explains.

A Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) report in 2016 found that 41 out of the 74 Tier 2 cities surveyed exceed the pollution hazard threshold. The awareness in official circles has been around but it has not translated into action on ground. This is critical as climate change impacts intensify and worsen the pollution. The list of the top 20 polluted cities in the world has 15 small- and mid-sized cities from India. All these cities have annual PM2.5 levels that exceed the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline by over 10 times, shows a recently released report Declining Air Quality in Small and Mid-Sized Cities, by urban issues think-tank Nagrika. It highlights how smaller cities are grappling with the impact of deteriorating air quality, focuses on the issue of non-stringent guidelines in tracking Air Quality Index (AQI), and the fact that smaller cities suffer from insufficient monitoring infrastructure.

Begusarai, in this report, is joined by Bhiwadi in Rajasthan as some of the most polluted small cities in India. On October 29, Bhiwadi recorded an AQI of 437 – much higher than the Delhi average AQI that day. Its high industrial output has been blamed for the severely hazardous air. The urgency is that if effective measures are not taken now to address such severe pollution levels, not only will India’s Net Zero target (to bring down emissions to zero) be undermined but also these cities will be uninhabitable in a few years.

Case studies: Bhubaneswar, Pimpri Chinchwad

On December 4, Odisha’s capital Bhubaneswar registered an AQI of 266 – higher than the national capital that day at an AQI of 178. The following day, besides Bhubaneswar, cities like Angul, Cuttack and Balasore in the state ranked among the 20 most polluted cities in India. Angul topped the chart with an AQI of 332, followed by Agaratala (315), Howrah (314), Byrnihat (312) and Amritsar (270).[3]

Bhubaneswar, with a population of 12.4 lakhs, grew by 31,610 in the last year which represents a 2.51 percent annual change.[4] Like any other Tier 2 city, Bhubaneswar, among the first three planned cities in independent India,[5] is expanding rapidly, witnessing rampant constructions, and unplanned growth. “Tier 2 cities are seeing an increase in population and in vehicles,” explains Debadatta Swain, Associate Professor (School of Earth, Ocean and Climate Studies), IIT-Bhubaneswar. “For a city like Bhubaneswar, air pollution is primarily from constructions as there are no factories nearby and vehicles are comparatively less. Most vehicles are from the nearby districts which pass through Bhubaneswar.” The city gets an average reading from its six pollution monitoring stations.

Photo: Krishna Jenamoni/ Wikimedia Commons

Studies have shown that all areas in cities are not evenly polluted. Some record higher levels of pollution because of various factors, as this[6] showed: “While air pollution affects all regions, there exhibits substantial regional variation in air pollution levels. For instance, the annual mean concentration of fine particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 μμm (PM2.5) in the most polluted cities is nearly 20 times higher than the cleanest city, according to a survey of 499 global cities.”

Cities such as Bhubaneswar have multiple microclimate zones with unique conditions that influence pollution. “There is an internal variability. Climate change affects the microclimate which, in turn, will also affect the climate,” says Swain, who has been researching urban climate, urban climate and microclimate. Old Town area and the newly developed Patia are the most polluted in Bhubaneswar.

Pimpri-Chinchwad, expanding twin cities between Mumbai and Pune in Maharashtra, is known as an industrial hub. Its vehicular population saw a sharp rise over the past few years, almost equaling its population of around 25 lakhs. The Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal’s Corporation’s Environment Status Report 2021-22 put the vehicles at 18.68 lakh.[7]

On December 1, several parts of Pimpri-Chinchwad recorded high air pollution levels with areas such as Bhosari, Moshi, Chikhali, Kudalwadi, and Jadhavwadi showing AQI levels exceeding 300. Experts attributed this to the rising vehicular pollution, industrial emissions, and ongoing construction activities.[8] The rising pollution levels prompted the municipal corporation to initiate the GRAP (Graded Response Action Plan) to manage air quality through its recommended structured approach. A dedicated agency has since been appointed to monitor and control environmental violations and waste-related issues.[9]

Rapid urbanisation or construction, insufficient green buffers, and industrial activities have been cited as the causes of critical pollution hotspots in Pimpri-Chinchwad, Hyderabad, and Chandigarh in the report Respirer Living Sciences[10] released earlier this month. It included location-specific average CPCB data for November 2024 across 10 cities but also integrated hyper-local monitoring and analysis.[11] Reports such as these should be a wake-up call for authorities.

Smaller cities lack proper data

The challenge should be to maintain healthy air quality but it begins at an earlier point – data. Smaller cities and towns not only suffer toxic air but also a dearth of monitoring stations and equipment. Only 12 percent, or 476 of India’s 4,041 Census cities and towns have air quality monitoring stations; only 200 of these cities monitor all six key criteria pollutants, according to a report by the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). Most manual monitoring stations, when they function, do not meet the minimum requirement of 104 days a year.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“The current monitoring network also faces the challenge of inadequate data generation, lack of data completeness and poor-quality control of monitoring. This makes air quality trend assessment difficult to establish compliance with clean air targets. The current urban monitoring grid is highly concentrated in a few big cities and there are vast areas in other regions with no monitoring. This needs to be rationalised to cover a wider population and habitats, to support implementation of clean air action plans, provide information to the public about the daily risks and design emergency response and longer-term action,” says Avikal Somvanshi, Senior Programme Manager, Urban Lab, CSE.[12]

The National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), which promises to make a difference to the Tier 2 and 3 cities, aims to reduce PM10 by 40 percent or achieve the national standard of 60 micrograms per cubic metre by 2025-26. But is it on course? Its funds are under- or improperly utilised[13] and cities under its ambit have recorded a rise in pollution levels. Major allocations have been given to cities with relatively low pollution levels, and the programme has primarily focused on addressing road dust rather than the broader air pollution issues, experts say.

Between 2019 and 2024, the NCAP allocated Rs 10,595 crore to states for the 131 non-attainment cities on its watch. Of the 131 cities, nearly 30 do not even have continuous ambient air quality monitoring stations, says Sunil Dahiya, Founder and Lead Analyst at Envirocatalysts, who co-authored the report, Tracing the Hazy Air 2024: Progress Report on National Clean Air Programme (NCAP).

With the lives and health of nearly 295 million Indians at stake from air pollution-related ailments in these cities, the fact many of them are ill-equipped to even measure pollutants five years after the programme was rolled out is a cause for concern.

Continuous ambient air quality in Tier 2 and 3 cities has expanded in the past four-five years to 550 stations now but most still have only one or a couple of monitoring stations. That’s not a good way of monitoring, says Dahiya. But what are the funds used for? A recent report by CSE found that funds were spent on dust management, paving roads, covering potholes, and deploying mechanical sweepers and water sprinklers; less than one percent was spent on controlling toxic emissions from industry and around 40 lie unused.[14]

Possible solutions

Bhubaneswar and Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (formerly Aurangabad) in Maharashtra are among India’s 131 non-attainment cities that have consistently failed to meet the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for five consecutive years. Pimpri- Chinchwad and Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar have proposed to set up low-emission zones, or LEZs, in one or two densely populated areas by 2026. In Bhubaneswar, the Odisha State Pollution Control Board has planned a LEZ for the old town area around Lingaraj Temple and Ekamra Kshetra Heritage Zone, which has high concentration of PM2.5.[15]

However, the battle against air pollution has to be a concerted effort to mitigate and also to adapt to cleaner energy. According to Bhattacharjee, state governments should provide grassroot involvement to tackle the hazard: “Most states have a state-level policy for curbing air pollution but most of it is on paper. Only a few Tier 2 cities in Maharashtra and Odisha have plans to establish low emission zones, vertical gardens on buildings and other infrastructure, but these are plans,” she says.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While these measures should become more common, construction sites need attention too. The rapid urbanisation calls for clearly demarcated containment zones, suggests Professor Swain, adding that the construction activity should not be allowed throughout the year. “Earlier, cutters were used but now, it is all mechanical. So, the particles in concrete or asphalt are cut into very fine particles. We don’t notice it but we are breathing a lot of dust,” he explains.

The measure everyone recommends: Plant more trees. This has to be done with care and knowledge to include native trees, protect the existing tree cover rather than seek permissions for hacking trees for construction, digging deeper pits, and so on. “Shrubs are effective too, they are like a net-and-trap for pollutants,” says Swain.

According to Dahiya, bringing more cities in the NCAP list brings attention, enhances accountability, transparency and maybe efficiency of actions. “The scale of the problem is big so we need to respond with that intensity. In every city, there should be a discussion about the four-five major sources of pollution. The percentage might vary for each sector depending on whatever activity is happening in those cities, but actions can start,” he says.

It’s high time that the lens of the authorities and national media included the cities and towns beyond Delhi and Mumbai. Else, the air pollution crisis will likely turn into a pan-India urban crisis.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about climate change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons